In observance of Veterans Day, we profile five early workers who served in the Civil War and later the Cause of Christian Science.

“How many are there ready to suffer for a righteous cause, to stand a long siege, take the front rank, face the foe, and be in the battle every day?”1

Posed to an audience in 1888, Mary Baker Eddy’s question is just as relevant today. While she may not have been a military general, she was accustomed to leading on a different kind of battlefield — a spiritual one fought on behalf of all mankind. As such, she was ever in search of faithful soldiers who had a willingness to fight in what she termed this “most unprecedented warfare.”2

Of the many who answered her call, there is a particular group that deserves recognition, given the upcoming observance of Veterans Day in the United States. These were individuals who were not only foot soldiers in the Christian Science movement, but also veterans of America’s Civil War. With this background in common, they were found by Mrs. Eddy to be particularly well-suited for service on the front lines of her rapidly growing Church.

Mrs. Eddy’s high regard for veterans was on display at a special Fourth of July event in 1897. Nearly 2,500 members of The Mother Church visited Pleasant View, her home in Concord, New Hampshire, to hear a program of speakers and to meet Mrs. Eddy herself. A group of honored guests — not all of them Christian Scientists — were given pride of place on the front porch. Among them was a general from the Battle of Gettysburg; a granddaughter of Abraham Lincoln; and four gentlemen with the dual distinction of being veterans of both the Civil War and the Cause of Christian Science.3

These Christian Science war veterans are profiled below.

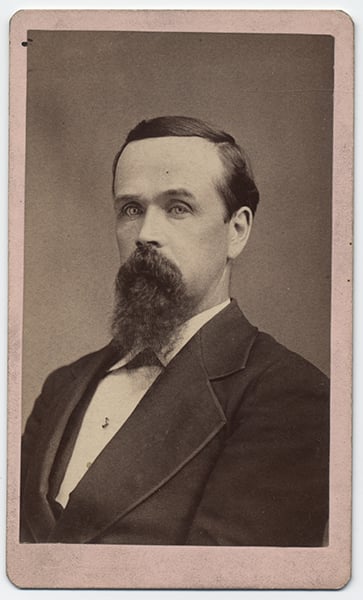

Judge Septimus James Hanna

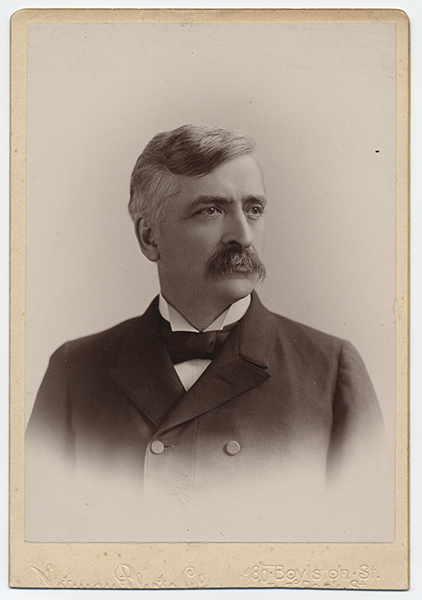

Aside from Mary Baker Eddy, perhaps the speaker most recognizable to the crowd that day was Judge Septimus J. Hanna. Most of the audience had likely attended the Communion service at The Mother Church in Boston the day before, where they would have seen Judge Hanna in his role as First Reader. It was a post he had held for several years and would hold for several more — evidence of the trust that Mrs. Eddy placed in him as a dependable lieutenant. Hanna had some prior experience in this regard.

Thirty years earlier, a 20-year-old Hanna enlisted in the Union Army. It was 1864, three years since the Civil War had begun, with another year to go before it would be over. To help create a strategic surge of Northern forces, the Union was enlisting Midwesterners into volunteer regiments with 100-day contracts. On June 21, Hanna and his brother William enlisted in the 138th Illinois Infantry at Camp Wood in Quincy, Illinois. Septimus Hanna was appointed captain of Company H, which consisted of 63 men. His 2nd Lieutenant was his brother William.4

The mission of the 138th was to protect the Trans-Mississippi region from mainly guerilla Confederate forces. Their assignments included garrison duty at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, and protecting supply and communication lines in the greater St. Louis region. When rebel forces under the command of General Sterling Price threatened to sweep through the area, the 138th volunteered to extend their contract until Price and his soldiers had retreated.

With his 100-day contract fulfilled, Hanna mustered out in October 1864. After his discharge, he practiced law in Iowa, then Chicago, then moved to Leadville, Colorado. His position there as Registrar in the U.S. Land Office is likely where the former Union Army captain took on the title of Judge.

In 1886, Hanna’s life and career took on a new direction when his wife, Camilla, was healed by reading Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy. He began studying Christian Science, and the next few years show his steady service to the Cause. He took Primary class instruction from J. S. Norvell of Iowa in December 1886 and began corresponding directly with Mrs. Eddy the following year. In 1890, he answered a call to serve as a Christian Science pastor in Scranton, Pennsylvania (this was before the implementation of Readers in Christian Science churches). Two years later, he accepted Mrs. Eddy’s request that he move to Boston and take the helm of the Christian Science periodicals.

In 1893, when Mrs. Eddy was searching for a new pastor of the Boston congregation, she wrote Hanna, explaining that the right candidate “would hear and obey the divine order. No matter if he could not stand face to face with the Father, he would obey without it.”5 Hanna’s reply the next day says much about his perspective on leadership, loyalty, and service:

He would be a poor general who did not issue his orders and place his men, to meet the tactics of the enemy. And he would be a worse than useless subaltern who did not promptly obey those orders though they changed an hundred times a day.… When I enlisted in this Army I enlisted to obey orders. We are under divine orders, and you are their interpreter.6

Hanna served as pastor and then First Reader of The Mother Church from 1894 to 1902. Additionally, he took on numerous other duties over the course of his thirty-year career, from editing the Christian Science periodicals to serving on the Bible Lesson Committee, the Board of Lectureship, and the Board of Education.

Captain John Freeman Linscott

Another featured speaker at the Fourth of July gathering in 1897 was introduced as “an old war horse.”7 Like Judge Hanna, Capt. John F. Linscott was on the front lines of the growing church. A newspaper account of his speech notes how in his usual vigorous and telling manner, he “rang out in stentorian tones, words of love and help to all,” proclaiming “God is all in all; this is our Declaration of Independence to the whole world.”8

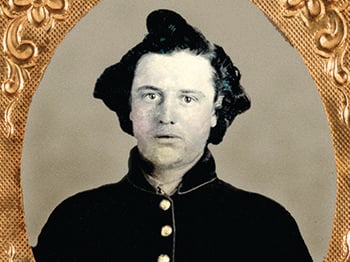

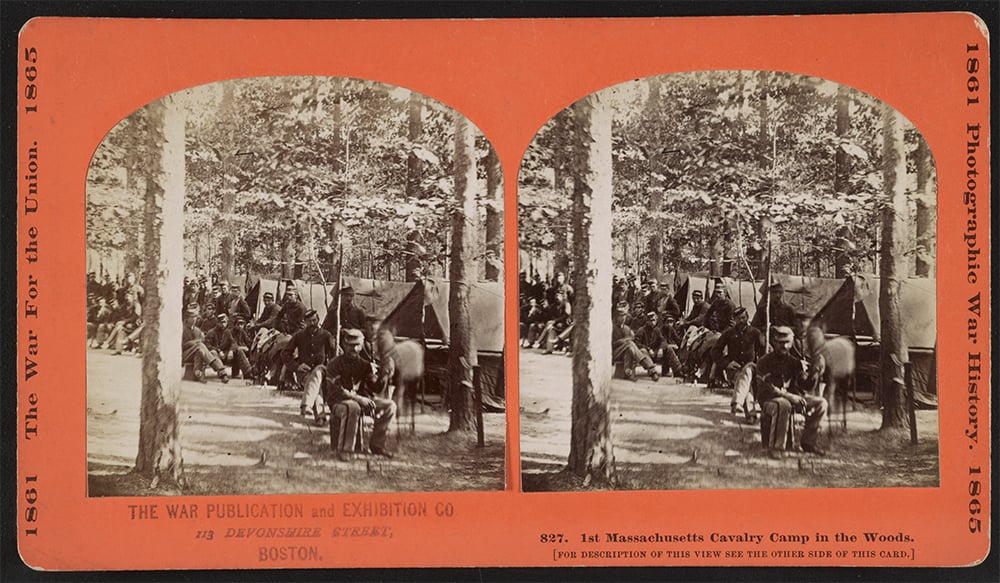

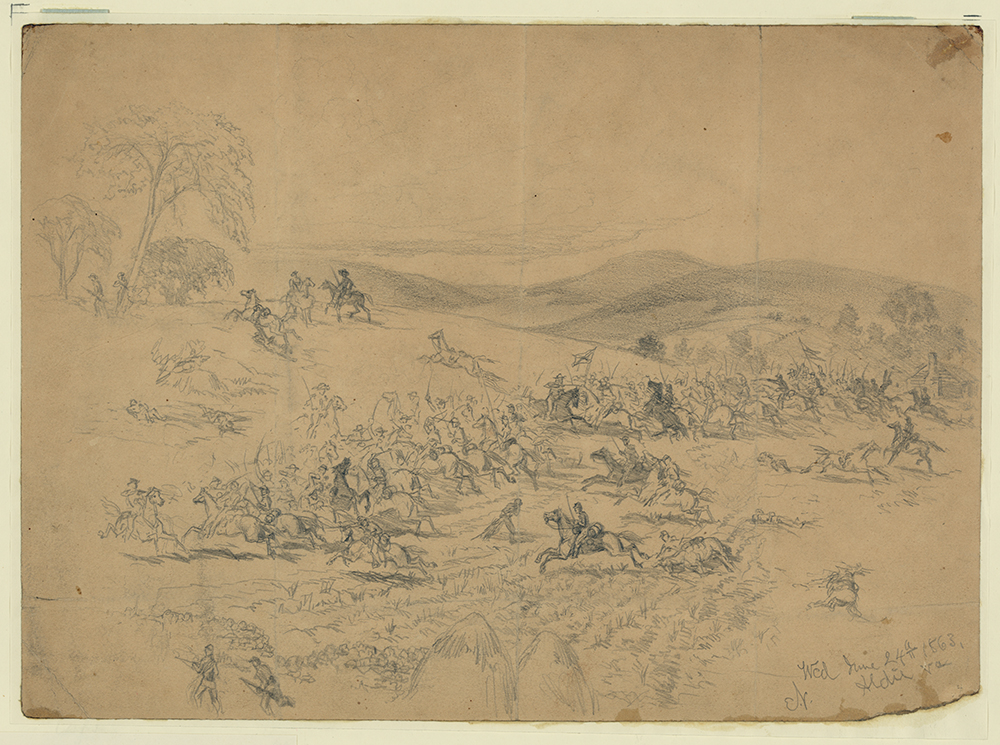

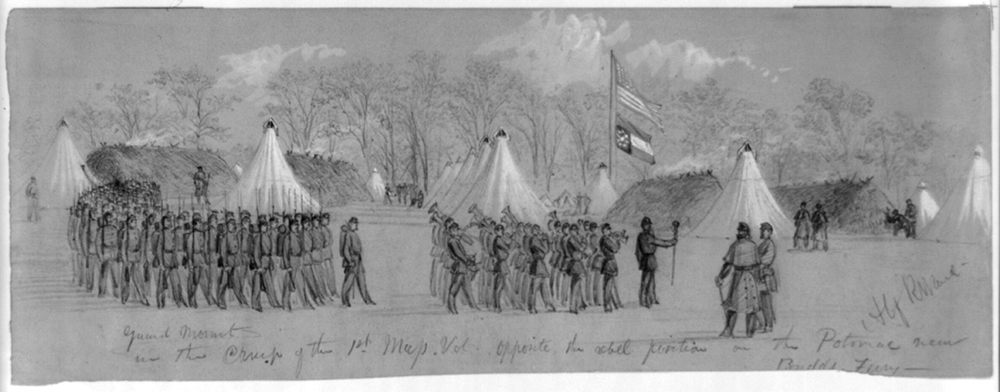

Mr. Linscott grew up in Massachusetts and as a teenager spent four years working on a whaling ship out of New Bedford.9 As the Civil War was escalating in 1862, he enlisted in Cambridge as a Private in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, Company A.10 He was 26 years old. The regiment was assigned to Washington, D.C., to reinforce the Army of the Potomac, which was the main Union fighting force in the eastern theater. Their list of campaigns throughout the war would be long, including battles at Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg.

Linscott had a couple of close calls during his enlistment.11 In February 1863, while destroying a railroad line, he fell and injured his back, removing him from duty for a month. Later, in June, the regiment was fighting in Aldie, Virginia, when Linscott’s unit was surrounded by the enemy and cut down with gunfire. Linscott’s horse was shot and he took a bullet through the leg, but he managed to hold out until being rescued. After a month in the hospital, he was released and returned to serve the remainder of his contract, mustering out in October 1864.12

After his discharge, Linscott remained in D.C., finding employment with the brand-new U.S. Secret Service. Before it was tasked with protecting the President, the agency primarily focused on stopping the circulation of counterfeit money. In these post-war years, however, Linscott struggled. He would later recount how the “saddening influences of the Civil War” pulled him into gloom and sadness, and how it was in this state that he made his first prayer to God.13

It would be another 10 years before Linscott found Christian Science. Meanwhile, he lectured on behalf of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, which was led by the prominent social reformer Frances Willard. Then, around 1886, he learned about Christian Science and quickly enlisted in its cause, a banner he would carry for the next 20 years.

In 1887, he took both Primary and Normal class instruction with Mrs. Eddy. During the following years, he became a missionary of sorts, helping to establish Christian Science in a number of different cities, from Milwaukee, where he began preaching, to St. Paul, where he opened a Christian Science Institute, and on to Colorado, before becoming pastor of a Christian Science church in Chicago.14 Linscott nearly became the pastor in Boston, too, but ultimately he returned to Washington, D.C. He remained in the capital through at least 1904, where he did much good work to build up a congregation as a First Reader and lecturer. Although he eventually faded from the front ranks, all in all, Linscott was reported to have helped establish 13 different Christian Science churches in the United States and London.15

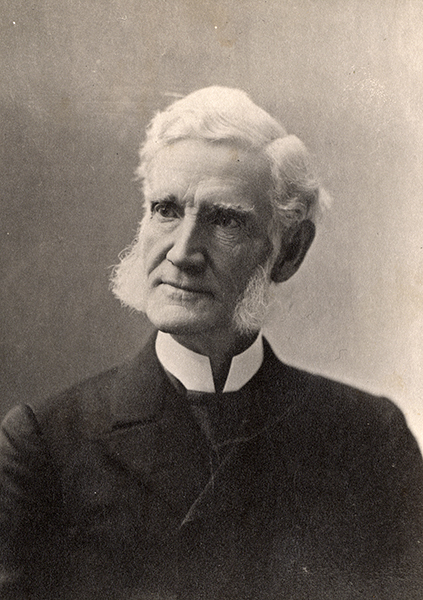

General Erastus Newton Bates

The honor of having the last word at the 1897 Fourth of July event at Pleasant View belonged to General Erastus N. Bates. The venerable white-haired soldier “spoke feelingly of what Christian Science had done for him,”16 explaining how it had restored him physically, mentally, and spiritually after his own harrowing war experiences.

General Bates was 34 years old when he enlisted in the Union Army in 1862. He had made a name for himself in law and politics as a delegate to the Minnesota State Convention, and by his election to the state senate in 1857. When war broke out, Bates put his career on hold and was commissioned as a Major in the 80th Illinois Infantry, Companies F and S.

Bates’s war took an unfortunate turn the following year. In April 1863, Colonel Abel Streight led Union forces, including the 80th Illinois, on Streight’s Raid, an offensive campaign through Tennessee and Alabama that targeted Confederate supply lines. There, they were pursued by the infamous Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest. On May 3, Forrest tricked Streight into believing he was surrounded by superior numbers. When Streight surrendered, his men were taken as prisoners of war.

Bates and the other officers were sent to the notorious Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia.17 Over six months later, he boldly escaped on his own, estimating that he made it about 18 miles before being recaptured. As punishment, he was put in a dark cell and given only water for several days, preventing him from taking part in the famous Libby Prison Escape in February 1864.18 After a hospital stay and a transfer to Morris Island, Bates was formally released in August, but he was in a sorry physical state when he arrived home, apparently weighing a meager 90 lbs.19

After recovering, the Major rejoined his regiment in 1865 and was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, then to Colonel. He took full command of the 80th until the war drew to a close. Two years after the war, Bates received an honorary promotion to Brigadier General by brevet.20 He resumed his involvement in Illinois law and politics, won election to the Illinois state legislature in 1867, then served two terms as state treasurer through 1874.

Although his life appears to have been on an upward trajectory in the post-war years, Bates apparently still struggled with some after-effects of the conflict. It was Christian Science, he proclaimed later, that “brought him out of what was virtually his grave.”21

He was introduced to it in 1886 when he attended a lecture by Hannah Larminie of Chicago. Bates began taking on healing cases that year, and in December he wrote his son:

I am very busy now days and expect to open an office in the city soon. My success in all cases acute, or chronic, nervous or physical is remarkable so far. And I see no reason why it should not continue. When I say my success, I do not wish to imply that I am the healer, for I am only the instrument used by God in this work.22

General Bates began corresponding with Mrs. Eddy in 1887, took Primary class with her in 1888, then Normal class in 1889. He was one of the few entrusted by Mrs. Eddy to teach at the Massachusetts Metaphysical College, and later he did much to establish the Cause in Kansas City and Cleveland. Looking back, he would with an overflowing heart tell the crowd at Pleasant View, “I owe all that I am and all that I have to Christian Science.”23

In praise of this steadfast soldier, Mrs. Eddy would later recall him with fondness as “one of God’s own noblemen.”24

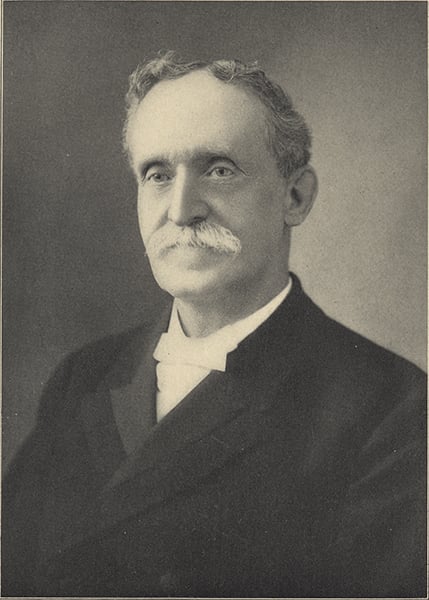

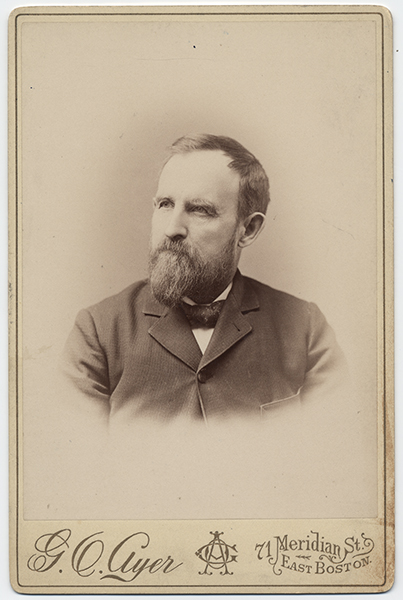

William B. Johnson

William B. Johnson was not a featured speaker at the Fourth of July event, but still an honored guest on the front porch. Like the old war horses General Bates and Captain Linscott, Mr. Johnson surely had some stories he could tell as his regiment saw much action in the Civil War. And as was the case with his other colleagues that day, it was in Christian Science that he had found a new cause to serve.

Johnson was born in England but grew up in South Boston, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1860. When the Civil War broke out in April 1861, he enlisted a month later as a Private. The 22-year-old joined the 1st Massachusetts Infantry, Company E, known as the Pulaski Guards.25 Upon completing training, they were immediately sent south to fight at Bull Run, one of the first big battles of the war.

Over the next three years, the 1st saw regular action, including battles at Chancellorsville, Williamsburg, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg. Not much is known about Johnson’s personal war experiences, but he mustered out with the rank of Corporal on May 25, 1864, after three years service. Although he apparently made it through the war physically unscathed, several health problems affected him for years afterwards.26

In 1882, at a medical specialist’s recommendation, Johnson turned to Christian Science. The vast improvement to his health so transformed him that he started his own healing practice the following year, and in 1884 he took Primary class instruction with Mrs. Eddy. However, these years were challenging for the family. Johnson gave up a steady income to devote his full time to supporting the early Church and his new practice. To make do, the family cut back financially; his son dropped out of school to earn extra income and later remarked that after a long day of work, he’d come home to a meager supper of stewed tomatoes and crackers.27

However, as the Christian Science movement grew, so did Johnson’s practice and his position within the Church. In 1888, he was appointed to the Board of Directors as Clerk. When the Church was reorganized in 1892, he was reappointed to these positions, which he held until 1909. In addition, he served on a number of different committees. In 1909, he focused full-time on his Christian Science practice.

An anecdote by Nelson Molway, who worked in the boiler room at The Mother Church, offers insight into Johnson’s perspective on rank and service: Called up to the Board offices one day, Molway, who was covered in soot from his work, stopped to clean up a little first. The dirt had kept him from being prompt, he told William Johnson, who kindly responded:

You must not think of your work as dirty. What you have to do is as important as what I have to do. You are doing things I could not do and I am doing things you could not do. Even the man who empties garbage is doing necessary work.28

Words of wisdom indeed from a battle-tested veteran, one who started in the lowest of ranks and rose to the highest. His nearly 30-year-career is the definition of selfless service.

Reverend Lanson Powers Norcross

One final Christian Science veteran who bears mentioning is Reverend Lanson P. Norcross. His life represents one lived in service to a higher mission, beginning with his four-year enlistment in the Union Army.

Mr. Norcross and his two younger brothers, Pliny and Frederick, joined the 13th Wisconsin Infantry in October 1861.29 They were part of Company K, of which Pliny was captain. The 13th operated in the Trans-Mississippi region, the same area in which Judge Hanna’s 138th would be active near the end of the war. In December 1862, elements of the 13th would pursue Confederate General Forrest’s men through Tennessee, several months before Forrest would capture General Bates.

Although the 13th saw action but a few times, they suffered numerous casualties due to disease, which was a widespread problem. Sadly, the Norcross brothers faced this when, in May 1865, Frederick passed away while stationed in Nashville. Coming so close to the end of the war, this must have been particularly hard for Lanson and Pliny.

After four years of service, Lanson mustered out in August 1865. He enrolled in Chicago Theological Seminary School and was ordained in 1870. The next decade was spent ministering all over the frontier. An interesting historical coincidence occurred in 1872 when he attended the General Congregational Association of Illinois. The convention moderator was none other than future Christian Scientist General Erastus Bates!

Norcross spent time in Wisconsin, Illinois, and Colorado, before being sent in 1876 to Deadwood, Dakota, where he organized the first Congregational society in the Black Hills. When he moved on in 1878, he just missed overlapping with Mrs. Eddy’s son, George, who was a veteran of the 8th Wisconsin Infantry. In 1879, George moved to Deadwood, then settled in nearby Lead.30 Norcross, however, had moved on to Nebraska by this time, before finally returning around 1883 to Wisconsin where he had started ten years before.

Around 1886, Norcross became involved in Christian Science.31 In the fall of 1888, he put his years of ministry experience to use when he became pastor of the Christian Science church in Oconto, Wisconsin — the first Christian Science church to have its own building for worship. That same September, Norcross also took Primary class instruction from Mrs. Eddy.

A fellow classmate, Joseph Mann, recalls an exchange that Mrs. Eddy had with one student who was a Civil War veteran — perhaps Norcross, although it may also have been her student Ira Packard. As Mann relates:

Another instance of [Mrs. Eddy’s] natural spiritual penetration is illustrated in the case of an old soldier-student in my class. This student had fought in the Civil War, and like many other soldiers had come out of the army with an old chronic trouble which neither surgery nor materia medica had healed. Mrs. Eddy one day suddenly turned to him and said, “Mr. So-and-so, you joined the army because of your love of right, to fight for the right and to save the Union, did you not?” The student hesitating, disconcerted, instantly convicted, replied, “I don’t know, Mrs. Eddy, I think I joined the army for the bounty that was offered.” Again Mrs. Eddy laughed with such heavenly satisfaction as to make me feel that the whole world was laughing with her; while my Grand Army classmate blushed with confusion, no longer wondering why he was still selfish enough to be ailing.32

After a year preaching in Oconto, Norcross received a letter from Clerk of The Mother Church and fellow veteran William B. Johnson. The letter invited Norcross to accept the pastorate of the Boston congregation, with a start date of just a week and a half away!33 Norcross’s reply sums up his commitment to serve: “… I come with but a single purpose i.e. to do all in my power to build up the one cause so dear to us all and grateful for any place be it ever so small in which to do it.”34

Norcross moved to Boston and began preaching. He assumed other responsibilities as well, including serving on the Bible Lesson Committee and helping to prepare the landmark 50th edition of Science and Health. In 1893, Norcross resigned from the pulpit but continued to serve by returning to the field work he’d done for so long, this time in Colorado. There, he and fellow veteran Captain Linscott did much to establish the Cause of Christian Science.

Norcross passed away in 1896, but if he had been at the Fourth of July event in 1897, he surely would have been one of the distinguished guests. An indication of Mrs. Eddy’s high regard for him is evident in the fact that just a few months earlier, she had referred to him as one of her best students gone too soon.35 A soldier, a pioneer, and a preacher — the Reverend’s life was one lived in service to a higher calling.

Together, these vignettes of just a few Christian Science veterans illustrate Mrs. Eddy’s statement, as true today as it was then: “The characters and lives of men determine the peace, prosperity, and life of nations.”36