Mary Beecher Longyear always loved the Bible.

From a young age, her mother’s “God-loving element” impressed upon Mary and her siblings the need for daily prayer and regular Bible study.1 But while little Mary was deeply attentive whenever her mother read aloud from the Scriptures, she was equally curious and often asked her mother questions about what she was reading. The answers, though well-meaning, were never satisfying.2

When Mary became a district schoolteacher at age 16, she taught her students to commit to memory chapters in the Bible, which they recited at morning exercises. And when she had children of her own, the first lessons she taught them were from Bible stories.3

When her third child suddenly passed on, Mrs. Longyear turned to the Bible for comfort and began earnestly searching for “a living God.” She also read books on philosophy and homeopathy, but once again, the answers they offered her did not satisfy.4

Some years later, Mary met Sue Ella Bradshaw, a Christian Science practitioner who was a student of Mary Baker Eddy’s. Miss Bradshaw healed Mrs. Longyear’s baby son and shared her own healing through Christian Science. The meeting was life changing. “That convinced me,” Mrs. Longyear later wrote, “that there was a healing power based on understanding the Bible.”5

Over time, as Mary Longyear’s appreciation and understanding of Christian Science strengthened, so did her grasp of the Bible and she found herself more and more involved in projects related to these two great interests. “The history of Christian Science must prove the Bible true,” she wrote in her diary many years later.6

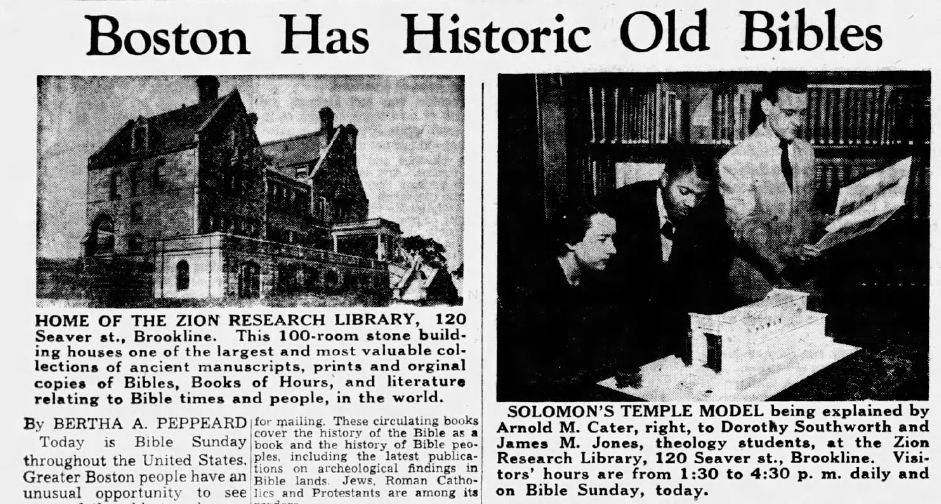

In 1910, Mrs. Longyear received a gift from the Christian Science Board of Directors of Mrs. Eddy’s grandmother’s spinning wheel, which launched her collection. In 1920, in need of an organization in which to house, catalog, order, and professionalize this collection, Mrs. Longyear took another bold step: She established the Zion Research Foundation – known today as the Endowment for Biblical Research – which is celebrating its centennial this year.7

The foundation’s mission was to “facilitate and advance research into the origin of the Hebrew religion, and to promote the more general study of that subject and its application to human needs.”8 To that end, it was tasked with collecting books and manuscripts related to the Scriptures, translating literature, financing individuals and institutions engaged in archaeology and research, and publishing, selling, and distributing periodic literature.

Mrs. Longyear was never quite able to recall exactly what it was that gave her the idea to create the Zion Research Foundation, “unless it sprang from a seed of desire planted in my heart when a young woman while reading a novel called Arius the Libyan.” The novel, based on the true story of Arius the presbyter (256-336 A.D.), who opposed Christendom on the nature of Christ and the Trinity at the Council of Nicaea in 325 A.D., must have stirred its reader.9

“The tribes of Judah and Benjamin and the ten lost tribes of Israel must according to prophecy gather at Jerusalem in Zion in the ‘latter days,’” Mrs. Longyear also later recalled. “So I accepted the name that came to my thought without question, ‘Zion Research Library.’”10

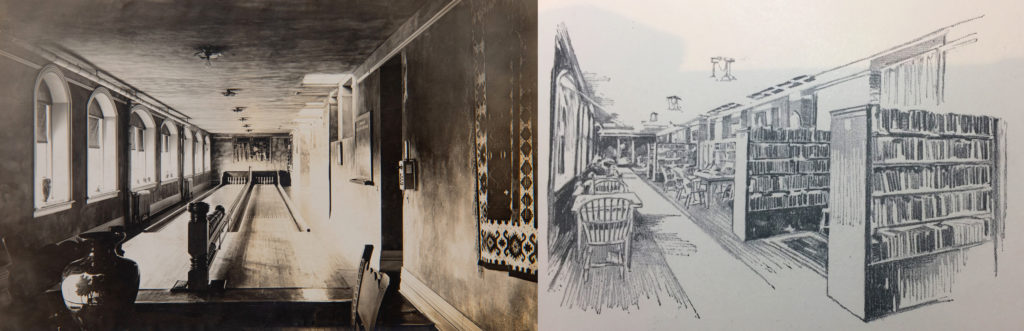

One objective of the Zion Research Foundation was to make literature available not only to scholars, but also to the average reader and seeker. “It is for the use of advanced students and interested searchers for the history of Truth,” noted Marguerite Smith, librarian of the organization from 1921-1955.11

“Not how large, but how choice,” was Mrs. Longyear’s motto as she carefully selected books to grace the shelves of her library, which eventually grew to some 13,500 volumes.12

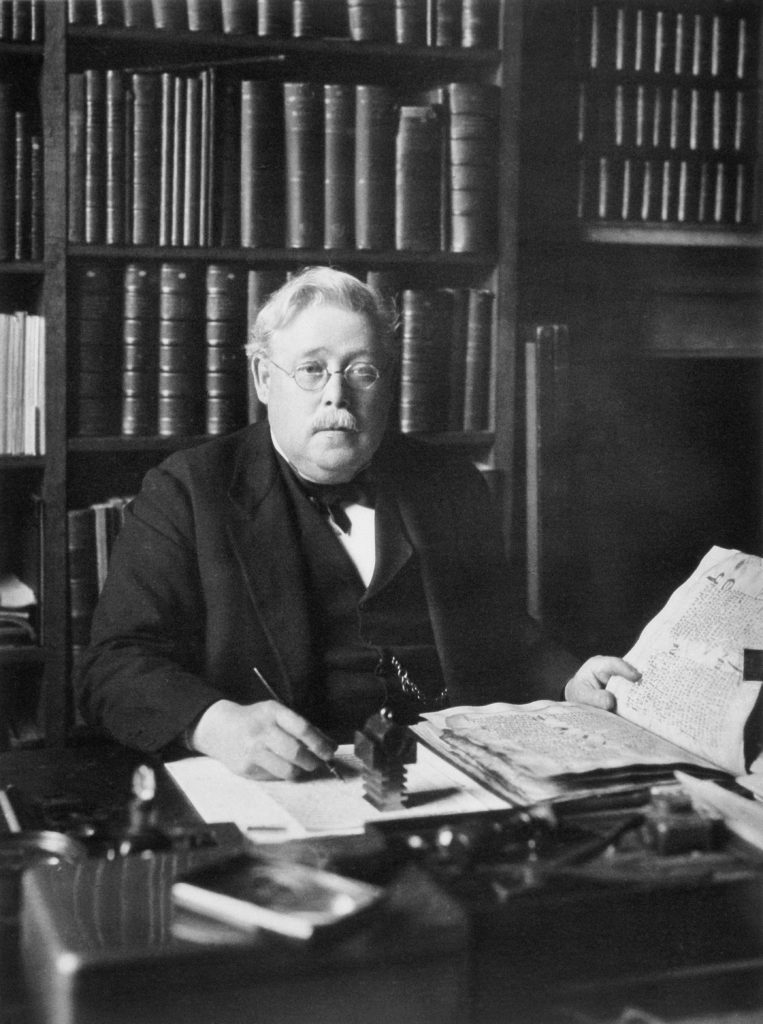

During the budding stages of the organization, Mrs. Longyear sought advice from professors at Harvard, Princeton, the University of Michigan, and the University of Pennsylvania.13 She also consulted Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge, the long-standing curator of Egyptian and Assyrian antiquities at the British Museum, who was an early enthusiast of her plans.14

In April 1920, Mrs. Longyear traveled to England and Scotland in search of books for her fledgling library. While in London, she met with Dr. Budge. He encouraged her efforts, suggesting titles that she might acquire and introducing her to rare book dealers.

“I know of nothing like it in the world,” he remarked about her library, “and I congratulate America on having the prospect of one. America must lead the world. Surely any nation that has ‘In God we trust’ on her copper pennies will succeed.”15

Meanwhile, the foundation was making steady strides in the fields of archaeology and translations. In the spring of 1919, Mrs. Longyear donated $10,000 to the University of Michigan for an expedition to Sinai and over the next five years financed the first printing of the Bible into Braille.16

Mrs. Longyear became a member of the distinguished Society of Biblical Literature in 1922. Zion Research Foundation was introduced at the organization’s annual meeting, held that year at the Yale Divinity School in New Haven.17 Two months later, the Zion Research Library officially opened its doors to the public.18

In 1925, Mrs. Longyear again attended the annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, where she gave a report on her foundation’s activities. That same year, she hosted the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, as well as the Special Libraries Association of Boston, in her Brookline home.19 Clearly, the Zion Research Foundation was becoming a name in religious and library circles.

Since that time, the foundation has continued to thrive. In the early 1950s, the library hosted the first public Dead Sea Scrolls exhibition in America (it later acquired a Dead Sea Scroll jar, one of only four in the United States) and in the late 1980s launched a public lecture series given each year at the annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature and throughout major cities in the United States. In 1976, the Zion Research Foundation changed its name to the Endowment for Biblical Research (EBR), whose mission is “to advance scholarly research into, and the general study of, biblical origins, shedding greater light on the meaning of the scriptural texts in the time they were first written and heard.”20

Currently, EBR is helping to fund an online research tool called the “Contexticon of New Testament Language.” Contexticon brings to light fresh possibilities for understanding Biblical terms and texts and examines how New Testament authors used words and phrases in comparison with usages found in other literature of the time.21

“Religion is the most vital subject to all mankind,” wrote librarian Marguerite Smith in an unpublished editorial for The Christian Science Monitor in 1933. “It is the study of the history of this interpretation as expressed in the Bible and by the Christian Church that the Zion Research Library promotes. . . . In point of time the subject is beyond comprehension and in point of breadth and diversion it is endless.”22

The steps taken on this “most vital subject” during the first century of Mrs. Longyear’s biblical foundation are admirable. The next century awaits!

To learn more about the Endowment for Biblical Research, visit www.ebrboston.org