The following is an excerpt from Homeward Part II: Chestnut Hill, which tells the story of Mrs. Eddy’s years at 400 Beacon Street. It is available for purchase through our online store.

At one o’clock on a cold, clear Sunday afternoon, January 26, 1908, Mary Baker Eddy stepped into her carriage for her daily drive. The carriage left Pleasant View, her home for more than fifteen years.

Her drive took her through downtown Concord, but today instead of returning to Pleasant View, she went to the depot in Concord, where a chartered three-car train had been waiting in the switchyard. A little before two o’clock the locomotive backed the cars into the station and most of her household staff boarded the last two Pullman cars. A few minutes later Mrs. Eddy’s carriage arrived.

She walked across the platform to the first car, used by railroad executives. She called for John Salchow, for seven years a faithful member of her household, to assist her into the car. The “watchers” — members of her household whose duties included metaphysical work — were in another part of this car, and during the trip she sent occasional instructions to them. When she was seated, the train started. After a while, Laura Sargent and Adelaide Still showed her to a sleeping room, and Miss Still urged her to lie down on the bed, which she did. They had not brought a blanket or robe, so Still took off her own coat and covered Mrs. Eddy’s feet.

The route would take them over three rail lines, and the schedule had been carefully coordinated with the regular trains using the same tracks. To ensure safety, a pilot engine left the station first, making certain that the track before them was clear. When this advance guard was a safe distance ahead, the train with its twenty or so passengers and crew pulled out of the station. A few minutes later, a second pilot engine, serving as rear guard, followed a half mile behind.

It was not long before wire services and telephones were buzzing with early news of her Concord departure, and with that, the journalistic hounds were on the scent to investigate: where was she going and why?

Traveling on tracks operated by the Boston & Maine Railroad, the train and its two pilot engines passed through Manchester and Nashua, New Hampshire. At three fifteen they arrived in Lowell, Massachusetts, having covered fifty miles in an hour. Three fresh engines replaced those that had come from Concord. To avoid Boston’s North Station with its anticipated crowd of reporters, the train was switched onto tracks of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad.

Outside South Sudbury it was discovered that an axle bearing in the last coach was overheating. The crew stopped the train several times to examine this potentially dangerous situation and applied snow to cool the bearing box. At four ten the train arrived at the second scheduled stop, South Framingham.

The special was switched onto Boston & Albany tracks, and superintendent Philip Morrison was on hand to meet it. The axle bearing was further examined, and it was decided to abandon the defective car. Its occupants and their luggage crowded into the second car, some of the men standing for the rest of the trip.

Three fresh engines replaced those from Lowell, and the forward pilot engine was a powerful “Berkshire” locomotive. A regular New York passenger train was held several minutes at South Framingham until the special had left and the track was clear.

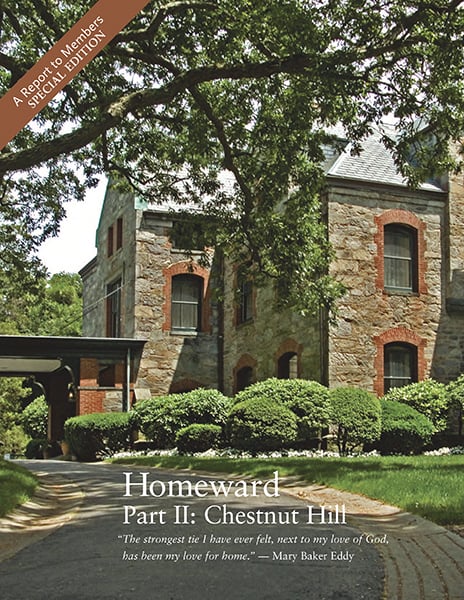

The train took off and raced to Riverside, where it was switched onto a branch line and arrived at Chestnut Hill station about four forty-five. Seven horse-drawn carriages waited to take Mrs. Eddy and her staff the last mile to their new home.

Although the journey was nearly ended, conjecture about Mrs. Eddy’s reasons for this momentous change was just getting underway. But Mrs. Eddy kept her own counsel and did not explain her reasons for coming to Boston.

Extraordinary demands would be made upon the leadership of the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science during her three years at Chestnut Hill. On the one hand, she increasingly required that those who served in church positions turn away from relying on her and seek divine direction. She was preparing them for the time when she would no longer be personally available for consultation or to extricate them from difficulties of their own making.

On the other hand, courage would be required of her to stand her ground in situations where her decisions would be challenged.

The record of her life at Chestnut Hill is one of restrained yet authoritative leadership. It is also a record of metaphysical reflection and exploration, as evidenced in the articles, published and unpublished, that she authored during this period.

Her years at Chestnut Hill are better understood if seen from the perspective of an ordeal she passed through the year before her move, an ordeal that challenged the very legitimacy of her leadership of the Christian Science movement….