This short excerpt is taken from a longer work profiling a number of early Christian Science workers who assisted Mary Baker Eddy in establishing Christian Science. Read their stories in full in Paths of Pioneer Christian Scientists.

As she moved down the reception line toward her teacher, Abigail Dyer Thompson was thinking how she would thank Mary Baker Eddy for what she had just received.

The November 1898 class had just ended and this smart-looking woman in her mid-twenties — one of the youngest of the group of sixty-seven mostly seasoned students — stood out like a bright spring flower.

Mrs. Eddy had selected the names for this class with great care, calling together not only the pillars of the current movement — the professorial likes of Judge Hanna and Edward Kimball — but also a small contingent of the up-and-coming generation who were fast making their way into the vineyard and taking up work alongside their elders.

As she often did at the beginning of a class, Mrs. Eddy had gone around the room addressing students, and arriving at Abigail’s mother, Emma Thompson, she singled her out for her years of faithful service in the vineyard — her extraordinary healing work that had become the talk of Minneapolis, resulting in extraordinary growth of the churches there.

But the next chapter of the Christian Science story was already being written. Indeed, in a mere thirteen months from this class, calendars would flip to the new year 1900, and from this threshold one could see the clutch of progress being let out on the twentieth century, sending incredible power to the wheels of American invention and industry. This was to be a century in which Christian Science would encounter both remarkable growth and startling resistance.

Mrs. Eddy saw this, her last class, as, in part, an invitation — calling new names to step forward to meet a new century’s challenges.

Abigail was one of those names.

Finally having worked her way through the line and reaching her teacher, Abigail shook Mrs. Eddy’s hand. She had decided that words were not up to the job of gratitude, and so, in effect, she offered her teacher a promise:

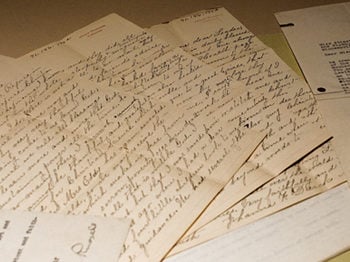

“I have no words to express my gratitude for the great inspiration you have given me, but I hope my life may,” Abigail said, as she recorded this encounter in her private reminiscence.

Mrs. Eddy placed her hand over Abigail’s, looked into her student’s eyes, and said: “It will, dear, it will.”

Walking out of Christian Science Hall into the streets of Concord that day after the class ended, Abigail was determined to turn her few words to Mrs. Eddy into a reality. Indeed, in the five-page account she wrote of what transpired in the 1898 class, her last sentence shows the compass course she had already set for herself:

“My greatest desire since that memorable day has been that some time my healing work may prove worthy of her inspired teaching.”

How Abigail brought that desire to fruition, taking the place alongside her mother as one of Minneapolis’s preeminent Christian Science practitioners for over half a century, is a story of dedication and love — love for God, Christian Science, and its Founder.

It is also a story of how focus, persistence, and hard work manifest an ideal, in this case a spiritual ideal, which would transform a young woman into a Christian Science practitioner whose career spanned the first half of the twentieth century, until her passing in 1957.

“The genius of progress is really the genius of work,” Abigail said in 1933, addressing fellow members of Second Church of Christ, Scientist, Minneapolis; it is “the ability to see a goal and move steadily towards it without wavering, in the spirit of St. Paul when he said, ‘This one thing I do,’ (Phil 3:13).”