In 1920, historic preservation pioneer Mary Beecher Longyear made her first purchase of a home that once sheltered Mary Baker Eddy. Now, Longyear Museum enters its second century of stewardship.

On the afternoon of July 7, 1920, Mary Beecher Longyear found herself standing in a potato field. She’d spent the day on the back roads and byways of New England, traveling from Barton, Vermont, where Mary Baker Eddy had once sought haven with friends following the passing of her husband Asa Gilbert Eddy, to Rumney, New Hampshire. There, she tracked down the owner of a “neat looking cottage with a most magnificent view.”1 The farmer was willing to sell, and Mrs. Longyear was eager to seal the deal.

It was, she would later write in her diary, “a most valuable day in the history of [Christian] Science.” The house had been home to Mrs. Eddy and her second husband, Daniel Patterson, at the onset of the Civil War. Mrs. Longyear, who had been collecting historical records about Mrs. Eddy’s life for several years by this point, was eager to preserve the house for the future. And so, with her chauffeur James Bonnar as “witness for the ages,” a deal was struck.2

With this potato field purchase, Mary Beecher Longyear stepped into the world of historic preservation, an arena so new that it didn’t yet have a term to describe it. There had been a handful of prior efforts on the national scene, including the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, formed in the late 1850s to help preserve George Washington’s home, but most others wouldn’t organize for decades. Colonial Williamsburg wasn’t founded until 1926; the United States National Archive wouldn’t be established until 1934; and the National Trust for Historic Preservation wouldn’t be launched until 1949.

“The most important thing in the whole world at this time, seems to me, is the preserving of the incidents and the authenticity of the history of the life of Mary Baker Eddy.” Mrs. Longyear wrote in her diary in 1923.3 A few years later, she expanded on this idea: “If the human life of Mary Baker Eddy is not recorded and guarded for posterity, in the years – yes, centuries – to come, legends will grow up regarding her, with no statements of Truth to refute them. . . . I am trying to forestall all rumors and misconceptions that might arise in the future, detrimental to her character and circumstances.”4

What Mrs. Longyear accomplished in a little over a dozen years is noteworthy, particularly for one with no background or training in historic preservation. Armed with an abiding conviction that “Love will point out the way,” as she put it, rock-solid determination, and her husband’s fortune (and willing support) to help fund her endeavors, beginning in the fall of 1917 she criss-crossed the country seeking out Mrs. Eddy’s students.5 She encouraged them and other early Christian Scientists to record their memories of their teacher as well as their own experiences as pioneers in the movement. She commissioned portraits of many of these early workers and collected artifacts, documents, photographs, and more. And with the purchase of the house in Rumney, her efforts expanded to include preserving a number of Mary Baker Eddy’s former homes.

In fact, 1920 turned out to be a banner year for this venture. That same July, she identified three more houses that had once sheltered Mrs. Eddy – one in North Groton, New Hampshire, that she would buy in November; the “Revelation House,” as she called it, in Swampscott, Massachusetts, where Mrs. Eddy experienced the transformative healing that led to her discovery of Christian Science, and which Mrs. Longyear purchased that summer as well; and a fourth house, in Amesbury, Massachusetts, which she would purchase in early 1922.6

Today, Longyear is entering its second century of faithful stewardship in caring for and sharing these important landmarks. Over the past 100 years, its collection of historic houses has grown from that first modest “cottage with a most magnificent view” in Rumney to include eight of Mrs. Eddy’s former homes in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. Each one has a story to tell; each one represents a step in her spiritual journey. And each time a visitor crosses the threshold of one of these houses and gains deeper insights into Mary Baker Eddy’s remarkable life, Mrs. Longyear’s forward-thinking commitment to preserving the history of the Discoverer, Founder, and Leader of Christian Science is once again reaffirmed.

An “ideal” childhood

So how did a former Midwest schoolteacher end up at the forefront of the historic preservation movement?

Born in 1851 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to Caroline and Samuel Beecher, Mary and her twin sister, Abby, were lively additions to a family that eventually grew to eight children. Mary describes their upbringing as “ideal,” in a home “where we learned to relish good literature and respect the authority and judgment of our parents.”7 Evenings found Samuel reading aloud to the family; Caroline, “whose word was law,” taught the girls to sew and all the children “to pray, to study the Bible and speak the truth.”8

When Mary was about five, the Beechers moved, first to Erie, Pennsylvania, to be closer to her maternal grandparents and later, in the winter of 1865, to a farm near Battle Creek, Michigan.9 School, church, chores, and social activities formed the pattern of their days.10

“Our parents realized our need at the early age of mental development and good society,” Mrs. Longyear later noted, “and at great sacrifice, at the early age of fifteen, [Abby and I] entered Albion College.”11

Dressed alike in stylish homemade clothes, the twins were “great belles, much to our delight,” frequently abandoning academics for social outings and stretching the college’s strict rules at every opportunity. “Our motto seemed to be ‘Circumvent the Faculty,’” Mrs. Longyear admitted with chagrin. “My love of fun led me into many daring chances . . . and unfortunately my twin followed my lead.”12

When their father showed up at commencement to see how his daughters’ education was progressing, the truth came out and the two were summarily brought home. This was a turning point for Mary, who developed a more mature outlook while at Battle Creek High School the following year. Wishing to contribute more to her hard-working family, she began studying in the evenings for the primary teacher’s exam unbeknownst to her parents. She passed and started looking for a job.

“I dressed in a subdued manner, took off my hoop earrings and the long curl that came from my chignon, and subduing my high spirits visited the school board,” she recalls, “and at the age of sixteen became the proud mistress of a charming white schoolhouse with a belfry.”13

Beginning with that first post in nearby Marengo, where she happily swept the premises every morning, rang the bell, taught class, and “boarded round,” all for the princely wage of twelve dollars a month, Mary embarked on a teaching career that would eventually take her to Michigan’s remotest region – and a future she never could have foreseen.

Meeting “Mun”

After further training at the State Normal School in Ypsilanti and several more teaching posts, Mary became intrigued by a classmate’s description of the freedom and beauty of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, bordering Canada and three of the Great Lakes. She set her sights on Marquette, a growing city located on the banks of Lake Superior, and duly sent off a letter of inquiry to the local school committee.

“I was so in earnest that I prayed over it,” she later wrote, “promising God if I got the place, I would not dance a step while I was there.”14

When she secured a post as principal of Marquette High School, she kept that promise, devoting herself whole-heartedly to the task at hand (while scrambling to keep one step ahead of her bright new students).15 No dancing didn’t mean no socializing, however. One Sunday, at the Presbyterian church where she worshipped, a tall, handsome young man with dark curly hair and beard – “the picture of health, energy, and manhood,” as she later described him – caught Mary’s eye. It was John Munro Longyear, son of a U.S. District Court judge and two-term Congressman from Lansing.

John was what was called a “landlooker” or “timber cruiser,” hired by investors to scout for land rich in valuable timber and mineral rights. The two were introduced, and after a whirlwind courtship, John returned to the woods engaged. They were married six months later, in January 1879.

“When I met the one man in the world whom I could thoroughly respect as well as love,” Mary explains, “I did not have a doubt, and short as our acquaintance was, we neither of us ever regretted our hasty action.”16

Theirs was a happy union that would last nearly half a century. She called him “Mun;” he called her “Molly.” Three children arrived in quick succession: Abby, Howard, and John. A savvy businessman, Mr. Longyear prospered, acquiring property of his own through partnership arrangements that entitled him to fifty percent of the land he scouted. He also managed vast tracts for large corporations, developed such natural resources as hydroelectric power and iron ore deposits that helped fuel the American Industrial Revolution, and leased property to mining companies, along with other lucrative ventures.17 Over time, he became “one of the most important and influential people handling Michigan’s natural resources.”18

But wealth couldn’t shield the family from tragedy. In the winter of 1884, 15-month-old John died while under medical treatment for a cold.19 The Longyears were grief-stricken at the loss of their little son.

“Sorrow has its reward,” Mary Baker Eddy writes in her primary text, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures. “It never leaves us where it found us.”20

This was about to prove true for the Longyears, as it was this tragic event that ultimately led them to Christian Science.

Two more children – Helen and Judith – were welcomed into the family over the following two years, bringing joy but also a sense of burden to their mother.

“I felt that all the responsibility of their well-being lay with me alone,” Mrs. Longyear later explained.21

Her minister offered little comfort, telling her that “God had sent the affliction of death to make me love Him more.” She’d lost faith in traditional medicine – “I had never given any of the children a drop of allopathic medicine since that fatal night” – and subsequently explored hygiene and homeopathy, all to no avail.22

“My fear of sudden disaster was terrible,” Mrs. Longyear noted. “I had no God to rely on. Medicine had failed me, hygiene was a mockery. I wanted to die and get rid of the responsibility.”23

It was at this juncture that she first learned of Christian Science, from a woman who had been healed of cancer by it. Mrs. Longyear would soon put it to the test. While on a trip to San Francisco, the family’s newest addition, baby Jack, developed a severe cough. At his frightened wife’s urging, Mr. Longyear reluctantly engaged a local Christian Science practitioner – Sue Ella Bradshaw, one of Mary Baker Eddy’s students.24 Their son was healed in one treatment.

Mrs. Longyear would later record: “We left for our home in Marquette the next day. I was happier than I had been since my little John Beecher left us. I felt that there was a God, and that He would take care of us.”

“A new ideal of life”

“I came back to my loved home with a new ideal of life and its possibilities,” Mary Longyear wrote. She began to teach some of the ideas she was gleaning from her fledgling study of Science and Health to her Sunday School class at the local Presbyterian church, where she and her husband were active members.25 Although they continued to attend services there, the family also read “the good lesson,” as Mrs. Longyear called it, from the Christian Science Quarterly each day together at breakfast.

Meanwhile, the Longyears were active in local society, entertaining family, friends, and business associates. As they prospered, they gave generously to their community, contributing time and money to a variety of civic causes. Mr. Longyear served two terms as Marquette’s mayor (1890-91) and the couple helped fund a college (Northern State Normal School, now Northern Michigan University), an opera house, and the Marquette County Historical Society. The Longyears also donated land for a new public library.

The whole family loved the outdoors. In the winter, there were skating and snowshoeing parties in addition to holiday balls; summers were for hiking, swimming, fishing, and boating at their cabin at the Huron Mountain Club, a private lakeside retreat 40 miles northwest of Marquette that Mr. Longyear helped found in 1889.

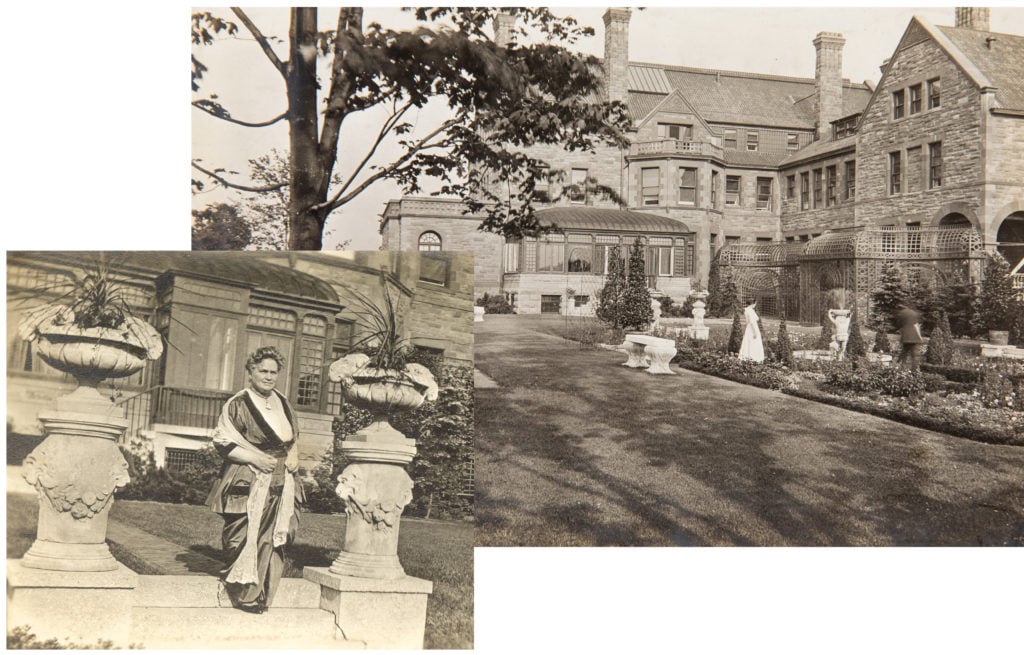

In 1892, the family moved into a mansion on a bluff overlooking Lake Superior. Built to their specifications of locally quarried Marquette raindrop sandstone, the impressive structure had 60-plus rooms and featured a third-floor ballroom and an octagonal central hall topped by a Tiffany glass dome two stories above the main floor.26

Mary continued her study of Christian Science, sharing it with others in the community, although her enthusiasm was not always warmly received. She joined The Mother Church in 1894, and accomplished some healing work in Marquette.27 A serious physical challenge of her own led her to two of Mrs. Eddy’s students – Caroline Noyes of Chicago, who healed her, and Mary Crawford of Cleveland, from whom she and Mun would receive Christian Science Primary class instruction in 1900.

Mr. Longyear was skeptical about the new religion at first.

“For several years I thought it had long hair and wild eyes,” he admits wryly in his memoir, adding that he “tolerated” it, “because it seemed to be doing Mary good.”28 His own healing of chronic rheumatism in 1897 changed all that.

“I thought that this would be a good chance to show [Mary] that where there was a real sickness Christian Science could not remove it and I said I would try it,” he recalls. By the second day of her prayerful treatment for him, he was entirely free of pain. “I waited three years for the rheumatism to return, but it did not. Then I made my tardy acknowledgment that . . . I had experienced an application of Divine Love in healing. The same Love that healed in Galilee nearly nineteen hundred years before.”29

By the mid-1890s, with the nation in the grip of a financial downturn, the Longyears decided to economize by temporarily shuttering their large home and taking the family abroad, settling first in Paris and later, Dresden. Mary continued to share Christian Science. She bought 100 copies of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, placing some at Brentano’s bookstore in Paris and sending others to prominent individuals in France and England.

Her seventh and final child – Robert – was born in Paris in February 1896. The following month, Mrs. Longyear wrote to Mary Baker Eddy for the first time, offering to pay to have Science and Health translated into French.

“She did not deny my request but said I might try to have it done,” Mrs. Longyear observed.30

Although her efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, from this beginning would grow a warm connection and a correspondence spanning 14 years and dozens of letters.

Another loss, another turning point

The Longyears returned to Marquette in 1897 and took up the reins of their former life. But Mrs. Longyear grew weary of the rejection she faced from old friends who “thought we were crazy to accept . . . Christian Science.”31 In the fall of 1899, she took the children to Boston to further their education. Mr. Longyear joined them as often as he could.

The couple traveled to the Paris Exposition in the spring of 1900, and Mrs. Longyear wrote to Mrs. Eddy again, this time requesting permission to display Christian Science literature there.

“Translate my tracts and as many others as you think best into the French language,” Mrs. Eddy wrote back from Pleasant View, her home in Concord, New Hampshire. “May God prosper your undertaking.”32

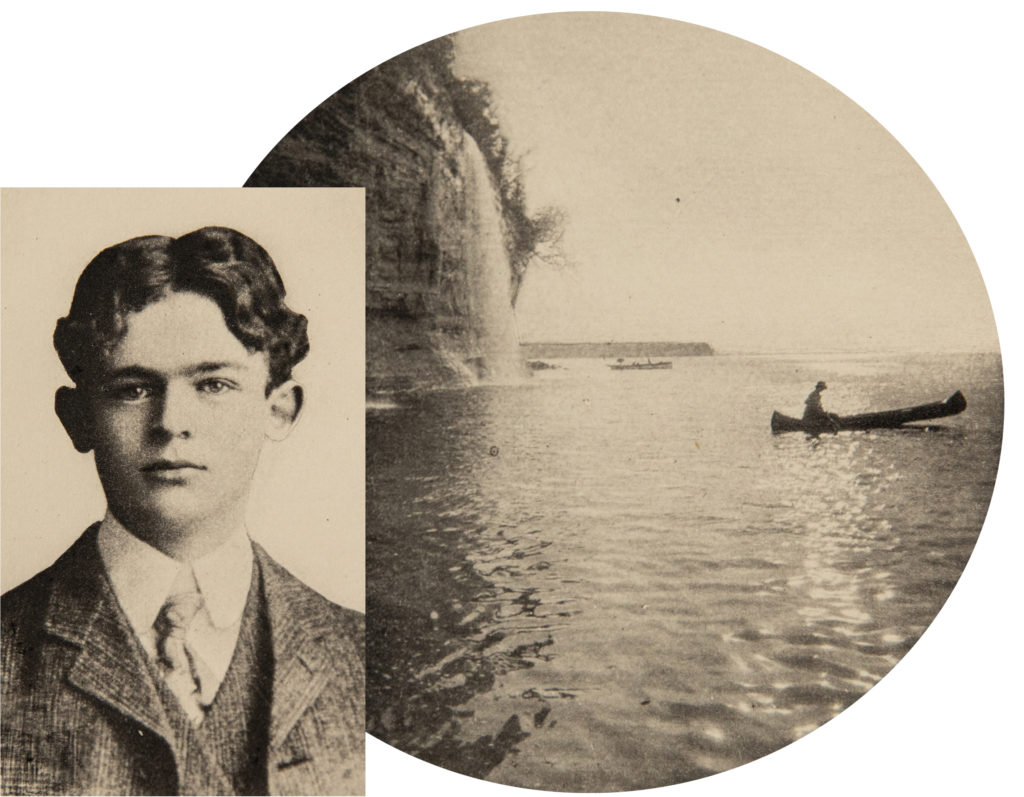

Howard, the Longyear’s eldest son, was at college at Cornell by this time, studying forestry with an eye to joining his father in the family business. Full of promise, he was the apple of his parents’ eyes.

“His sisters adored him and his little brothers returned his affection for them in full measure,” Mrs. Longyear wrote of Howard. “His letters from college were the most important event in all the world to us.”33

In the summer of 1900, the family returned to their cabin at the Huron Mountain Club for a vacation. Howard and a local friend set out in a canoe from Marquette, planning to paddle the 40 miles to join them. Howard was carrying books, mail, and flowers for his mother. But the two boys were caught in a sudden storm and drowned.34

It was another devastating loss for the family.

“Had it not been for my knowledge of [Christian] Science, I would have become a broken-down woman,” Mrs. Longyear later acknowledged.35

Just as had been the case earlier, however, this tragic event, too, would prove a turning point.

The Longyears soon faced another blow. Plans to donate a prime piece of lakeside property for a public park as a memorial to their son were derailed, quite literally, when right of way to the land was claimed by a railroad company. Neither Mr. Longyear’s offer to pay to reroute the planned line nor a lawsuit was able to stop it.

“Mun, I shall never go back to Marquette to live again,” Mrs. Longyear told her husband when news came of the Michigan Supreme Court’s verdict (the family was traveling abroad at the time). The thought of leaving her home in addition to losing her eldest son was a bitter one, however. “That night, when I wrestled with the sense of loss, the answer came, ‘Go to Boston.’”36

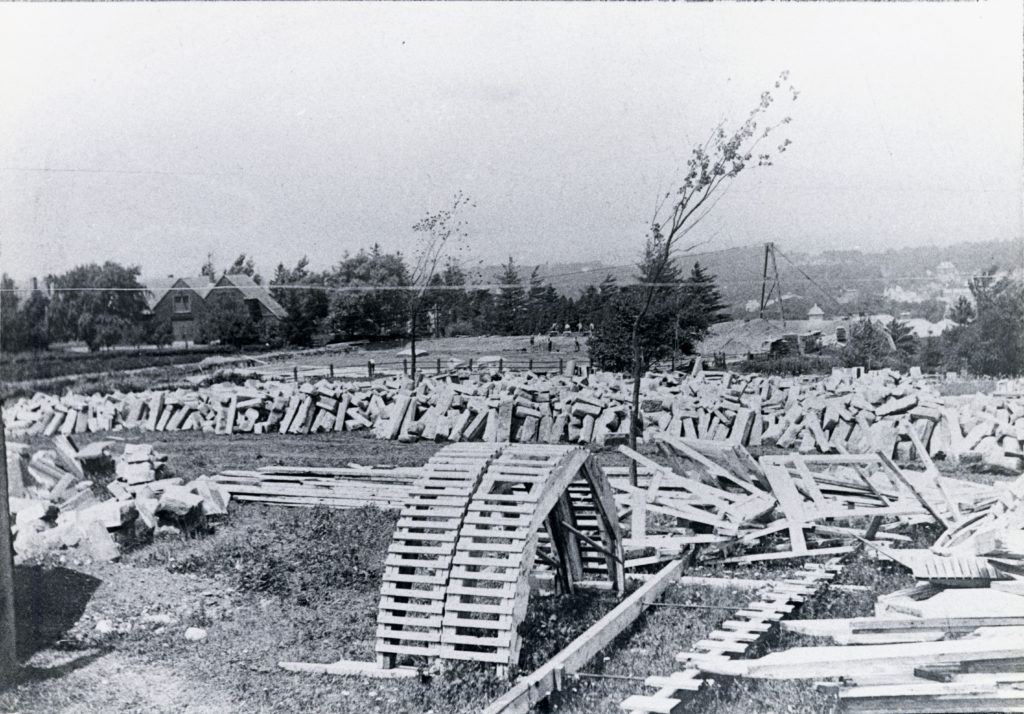

A short time later, the couple were riding in a carriage down the Champs-Élysées in Paris when Mr. Longyear made a startling announcement: “Wifey, I think we can move the house to Boston.”37

In a feat of engineering ingenuity that made headlines nationwide, that’s exactly what the Longyears did. It took three years, a team of 25 workmen, and an enormous sum of money, but the house was disassembled stone by stone, each one photographed, numbered, carefully wrapped in cloth and straw and crated for shipment by rail to Boston, there to be rebuilt on a hilltop in neighboring Brookline.38

Started in 1903 and completed in 1906, the move represented a new beginning for the family, and it was one that would bring Mrs. Longyear to the heart of the Christian Science movement, and ultimately to her life’s work.

“To be of real use to the Cause”

“The thought came to me forcibly today that the time to gather all data possible from the living people who knew Mrs. Eddy personally, is the present,” Mrs. Longyear recorded in the fall of 1917.39

The intervening years since arriving in New England had been full. The Longyears initially rented a home in Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood while their house was being moved from Marquette. The family attended The Mother Church, where Mrs. Longyear taught Sunday School. While Mr. Longyear commuted between Boston and Marquette to attend to his business operations, Mrs. Longyear attended to the education of their four youngest children – and to furthering her own understanding of Christian Science. In October 1903, she had Primary class instruction from Edward Kimball in Boston, receiving a C.S.B certificate at its conclusion.40

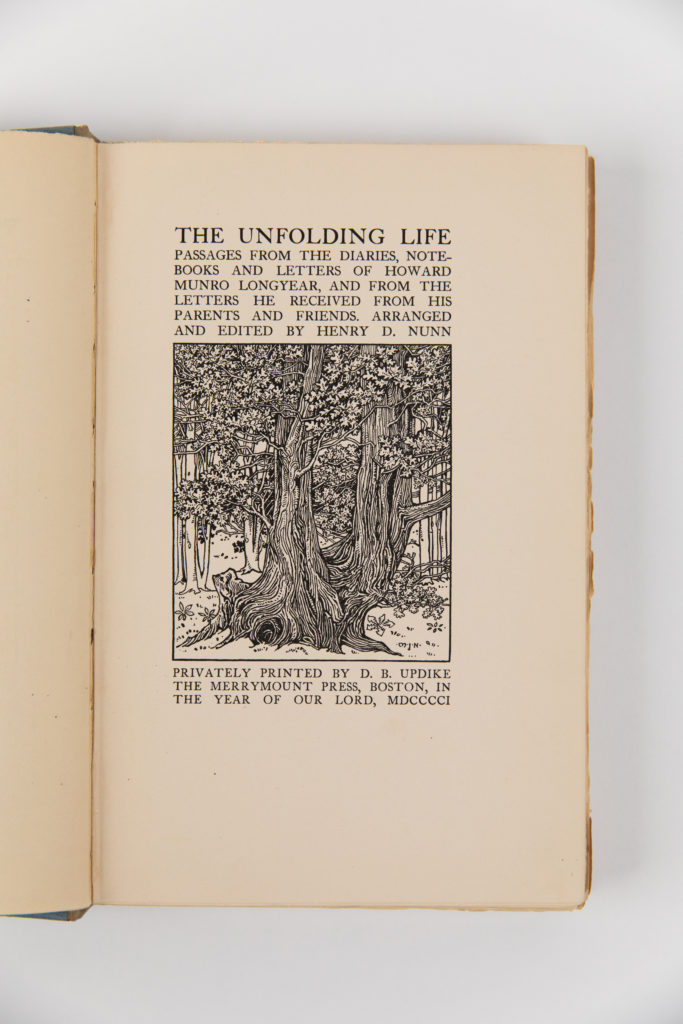

She also continued to correspond with Mrs. Eddy, and that same year sent her a copy of The Unfolding Life, a book that she and her husband had privately printed to honor Howard.41

“It is beautiful within and without,” Mrs. Eddy wrote in response. “You deserve a medal for its make-up, for the love that breathes in every line and lives in your heart.”42

Their correspondence over the next few years, Mrs. Longyear notes with commendable humility, “tell[s] the story of my efforts and, alas, my failures.”43 Gifts of food, flowers, clothing, and other items were kindly received – “I am again your debtor for luxuries and letters that came from a heart richer than the wealth of a world,” Mrs. Eddy wrote to her in 1904, for instance.44 In another letter she noted, “None can doubt your great beneficence, your unselfed love, your practical Christianity.”45

But Mrs. Eddy was as quick to rebuke as she was to praise when she detected too much focus on her personality or “untempered zeal on her behalf,” as Mrs. Longyear put it, that needed to be reined in.46

“Dear one: Turn your thoughts from the material to the spiritual, from dreams to realities,” Mrs. Eddy wrote kindly but pointedly in 1904. “Write and think no more about such things for me. I do not want them. Leave me out of your material concepts. Now if you love me you will obey me.”47

In June 1905, the Longyears were invited to Pleasant View.

“The greatest, most eventful day of my life,” Mrs. Longyear recorded in her diary of their visit with Mrs. Eddy. “May the blessing be absorbed.”48

Mary Longyear was active socially, entertaining at her newly-rebuilt and expanded home (named “The Terrace”), supporting the arts, joining clubs, and engaging in civic and charitable endeavors.49 Ever the practical Midwesterner, she offered financial support wherever needed, counting her deep pockets a blessing to be shared liberally.

Closest to her heart, however, was Christian Science, and a desire “to be of real use to the Cause.”50 At one point she purchased a piece of property from Mrs. Eddy to help relieve her of the financial burden, for example, and she and Mun gave generously toward the building of the Extension of The Mother Church, donated a parcel of land adjoining The Mother Church (now part of the Church Plaza), financed Frances Thurber Seal’s sojourn in Germany to sow the seeds of Christian Science, and offered to help build a Christian Science sanatorium.51

Through the Christian Science periodicals, Mrs. Eddy praised Mary Longyear publicly for her generosity:

We lose the sense of personality when describing love, and so base the behests of praise on worth akin to unworldliness, on goodness shorn of self, and on charity governed by God influencing the acts of men—even a charity which “suffereth long and is kind.”

Mrs. Mary Beecher Longyear’s charity is of the sort that letteth not the left hand know what the right hand doeth, that giveth unspoken to the needy, and is felt more than heard in a wide field of benefactions. Seldom have I seen such individual, impartial giving as this. Therefore I hasten to praise it and turn upon it the lens of spiritual faith and love, which enforce the giving liberally to all men and the upbraiding of none.

Begging her pardon for the presumption of my pen, if such it be to “render unto Cæsar the things that are Cæsar’s,” I hope that I have neither grieved her meekness nor overrated her generosity thereby.52

There was a second visit to Pleasant View, and later, when Mrs. Eddy moved to nearby Chestnut Hill in 1908, visits to her new home at 400 Beacon Street. In January 1910, Mrs. Longyear was invited to lunch. After enjoying a meal with Mrs. Eddy’s household – Calvin Frye, Irving Tomlinson, Laura Sargent, Adam Dickey, and William and Ella Rathvon – she was called upstairs to see Mrs. Eddy.

“I ran joyously up to her room,” she recalled of their laughter-filled conversation. “Such a vision. Lavender silk dress and white lace and wonderful eyes. She called me ‘our benefactor’ and . . . said ‘It is a joy to live for the good one can do.’”53

That summer, Mary Longyear received another invitation to Chestnut Hill. Fresh from a trip to Paris, she arrived bearing gifts for the household, including an Oriental rug for Mrs. Eddy.

“The bright joyful face of Mrs. Eddy greeted me. She kissed me and welcomed me. . . . She asked me if I knew the reason she liked to have me visit her. When I answered in the negative, she said, ‘It is because you give me nothing to meet.’”54

A week later, the Christian Science Board of Directors wrote to Mrs. Longyear to offer her a spinning wheel that had once belonged to Mrs. Eddy’s grandmother.55

While she wouldn’t formally begin collecting historical material until 1917 (aside from purchasing a marble bust of Mrs. Eddy by American sculptor Luella Varney Serrao in 1911), that generous gift was the start of what today comprises Longyear Museum’s extensive collection, all related to Mary Baker Eddy and the early history of the Christian Science movement.56

In September 1910, Mrs. Longyear sent Mrs. Eddy and her household a gift of fruit grown on her property in Brookline. A thank you note arrived promptly in return. It would be her last communication with Mrs. Eddy. Addressed “Beloved Student,” it contains a hint of Mrs. Eddy’s humor: “Allow me to wish you long years, life perfect and immortal. May God crown your years with blessings.” It was signed, “Lovingly yours.”57

The “cloud of witnesses”

In the years following Mary Baker Eddy’s passing, Mrs. Longyear’s philanthropy continued unabated. In 1911, she gave $10,000 for Mrs. Eddy’s memorial at Mount Auburn Cemetery and in 1916, she and Mun donated 20 acres (and later substantial funds) for what would become the Chestnut Hill Benevolent Association.58 During World War I, Mrs. Longyear supported war relief efforts, including one funded by The Mother Church.59

And in 1913, Mary Longyear quietly established a fund to help support early students of Mrs. Eddy’s, many of whom were quite elderly by this time and needed practical assistance and tender care. At her request, the fund was kept anonymous. Christian Science practitioner and teacher James Neal agreed to administer it. Later, after his duties as a member of the Christian Science Board of Directors necessitated his passing the baton, he wrote a letter to Mrs. Longyear. It read in part: “It has been a privilege to handle this fund for the letters from its beneficiaries show that in times of need it has brought comfort and cheer to those who so bravely stood by our beloved Leader during the early years of her struggle to establish Christian Science. Every bit of support she then received deserves a full measure of recognition from those who are now reaping the benefits of those labors, and for this reason The Board of Directors especially appreciate the practical way in which you are expressing yours.”60

Mary Longyear’s philanthropic endeavors stretched beyond the Christian Science movement. Her war relief efforts included sponsoring a benefit for the American Red Cross at her home in Brookline, and she and her husband helped fund the first translation of the Bible into Braille.61 In 1920, Mrs. Longyear established the Zion Research Foundation, transforming her home’s former basement bowling alley into a library for some 13,500 volumes on Bible-related subjects that she eventually amassed.

In addition to these activities, Mary Longyear was a painter and poet, wrote half a dozen books (including a biography of Asa Gilbert Eddy), and was active in the women’s suffrage movement.62 Always closest to her heart was the Cause of Christian Science, however. And in the fall of 1917, when that lightning bolt of clarity hit her that the time to gather information from those who actually knew Mary Baker Eddy – the “cloud of witnesses,” as she put it, echoing the Bible – was now, she didn’t hesitate.63 Within days she visited Julia Bartlett and Janet Coleman, two of Mrs. Eddy’s earliest students, and returned home with their photographs. From that point on, her collection began to grow.

“The Truth leads”

Mrs. Longyear was quick to acknowledge the part her husband played in her philanthropic endeavors, calling him “the avenue through which Love supplied me with the means to meet the needs of our beloved Cause of Christian Science.”64

He did more than just bankroll her efforts, however. As Mary threw herself heart and soul into the work, Mun was an active partner much of the time. The couple took trips together to seek out Mrs. Eddy’s early students and visit historic sites related to Mrs. Eddy’s life, collect books for the Zion Research Foundation, and much more.

“Mr. Longyear nobly helped me,” Mrs. Longyear wrote in her diary at one point.65

Through it all, Mary Longyear placed her trust firmly in God.

“God, my God, will lead me and will not let me make mistakes,” she recorded, and it’s fitting that the Greek equivalent of the Longyear family motto – “The Truth leads” – was placed by the couple on the Longyear Foundation seal. 66

Prayer undergirded all her efforts. One example serves to illustrate this point. In the summer of 1920, Mrs. Longyear and her daughter found the house in Amesbury, Massachusetts, where Mrs. Eddy lived on two occasions. But its owner had no interest in selling either the house or its contents – which had remained substantially as they were when Mrs. Eddy lived there.

“I could not buy nor beg for one single thing,” Mrs. Longyear lamented in her diary.67

As they left, she told her daughter, “Judith, if it is right for me to preserve this house, I will get it someday; if it is not God’s will, I do not want it!”68

A year and a half later, the house was hers.

“It was a gift from Love,” she recorded afterward in her diary. “I knew if it were right for me to guard it for the future, I would get it.”69

Working for the ages

The road that led Mary Beecher Longyear to that potato field purchase in New Hampshire in the summer of 1920 was a long and occasionally rocky one. There were personal as well as professional challenges. While many applauded her efforts, others questioned her motives, her methods, and whether it was even necessary to preserve Mary Baker Eddy’s human history.70

Mrs. Longyear was the first to acknowledge and express chagrin for her own shortcomings – her diaries are full of earnest resolutions to be more patient, less willful, and less impulsive – but she never wavered from her conviction that it was not just necessary to trace Mrs. Eddy’s human footsteps, but vital.71 She saw the work she was doing in preserving historical evidence as a safeguard for the future.

“The ages must be furnished authentic data,” she stated.72

Her son Robert Longyear later elaborated on the motivation behind his mother’s endeavors, observing, “The more complete [the factual record] could be made, the less opportunity would there be in succeeding centuries to fabricate tissues of imagination in order to vilify [Mrs. Eddy] or sanctify her.”73

Mrs. Longyear’s deepest hope was that her efforts would help encourage Christian Scientists in the coming years as they became better acquainted with those who had gone before – and above all, with Mary Baker Eddy.

“We must know her, her motives and her simple, natural life – know her struggles and her overcoming of them,” she wrote. “We must learn to endure and love as she did.”74

Acknowledging the long road that had taken them from Marquette to Boston and looking ahead to the future, Mary Beecher Longyear wrote in a note to her beloved husband in February 1920, “Our house was brought here for a good purpose, and from it will pour blessings from generation to generation.”75

If you’d like to help continue the work that Mary Beecher Longyear started, please click here to donate. We’re grateful for all of our supporters!