“Who Shall Be Called?” The Pleasant View Household: Working and Watching is the title of a 90-minute documentary released on DVD in November by Longyear Museum. The film covers the years when Mary Baker Eddy was founding the Church of Christ, Scientist, a period of great historical importance for Christian Scientists and the world. Producer Web Lithgow tells some of the behind-the-scenes story of why and how this film was made.

Heart to Heart

On Christmas Day, 1894, a heart-shaped wreath of dried roses was delivered to Mary Baker Eddy’s home, Pleasant View, in Concord, New Hampshire. It was a gift from groundskeeper John Austin and his wife. That very day the recipient sat down and wrote a thank-you note, with the wish: “May the dear Christ be born anew in all our hearts to-day, and each heart be as beautiful in His sight as your heart of flowers is in mine,” signing it, “With love, Mary Baker Eddy.”1

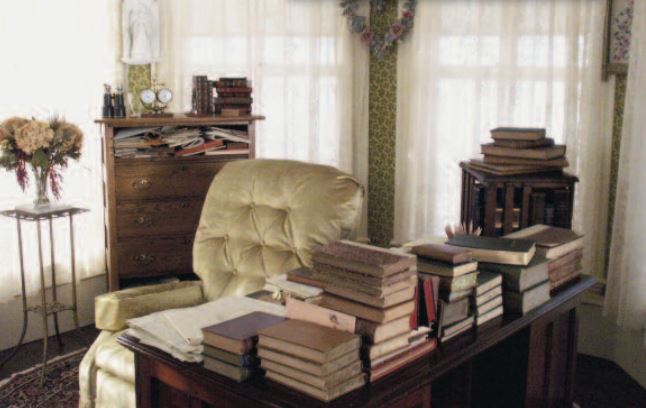

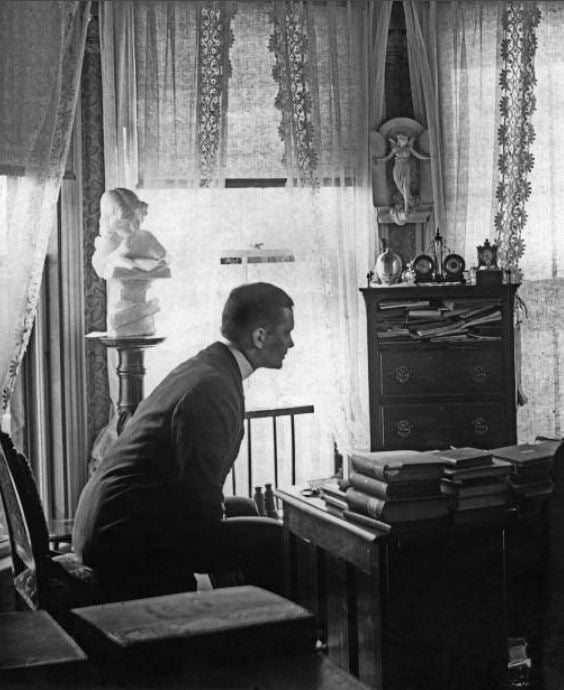

Mrs. Eddy loved hearts — and flowers. She must have particularly loved this wreath that combined both. She hung the bouquet in the bay of windows right by her desk. Sometime after the turn of the century her secretary, Calvin Frye, took some candid photos of Mrs. Eddy in her study. In the photos the heart still hangs where she had placed it years earlier.

To illustrate passages in the script for our documentary film about Mrs. Eddy and her household, a replica of her study at Pleasant View, which had been demolished ninety-one years ago, had to be constructed. Decorations for the study were recreated just as they appear in Calvin’s photos, including the heart of flowers.

Why, in an educational film, so much attention to such a small detail? This detail is a concrete reminder that on that Christmas Day, as the first service in the nearly finished Mother Church loomed less than a week away, and with all she had on her mind, the Leader of Christian Science took time to let the Austins know how their heart had touched her heart.

Roses and Ramparts

Pleasant View was, indeed, a place of rose gardens and peaceful vistas. But Mrs. Eddy also saw her home and headquarters as a fortress against which the malicious motives and acts seeking to destroy Christian Science and its Leader beat in vain. She recruited household helpers as “soldiers” to “defend this fort, and the officer working within it for her Church, the field, and the world.”2

Those who answered that extraordinary call might seem quite ordinary folk. They had been farmers, teachers, homemakers and cooks, a railroad man, a young clerk, a concert singer, a preacher, a machinist — backgrounds common to thousands of others. Hardly a brigade of soldiers!

What set this band of people apart? Mrs. Eddy answered this question in The Christian Science Journal of May 1903, under the heading “Significant Questions”: “Who shall be called to Pleasant View? He who strives, and attains — who has the divine presumption to say: ‘For I know whom I have believed, and am persuaded that he is able to keep that which I have committed unto him against that day’ (St. Paul).”3 As we researched, we found in that brief statement the title and theme for our documentary film about Mrs. Eddy and her household.

“Who Shall Be Called?”

The hundred-plus who were called to serve the Leader of Christian Science in a succession of homes at Boston, Concord, and Chestnut Hill are represented in this film by a selected handful of workers — Calvin Frye, Laura Sargent, Clara Shannon, Joseph Mann, John Salchow, Minnie Weygandt, John Lathrop, Adelaide Still, and a few others. This film tells their story — and the great story they observed.

Starting our research, we asked ourselves, What is that story? And what is the best kind of documentary for telling it?

The overarching story is the founding of The First Church of Christ, Scientist, The Mother Church in Boston, Massachusetts, and the establishing of Christian Science “on the Rock ’gainst which the billows break in vain,” as Mrs. Eddy expressed it.4 The film briefly looks back to the Lynn and Boston years of teaching and preaching. But the film’s main focus is on the period from 1889 to 1903. Telling about those years with sufficient detail required a feature-length, 90-minute documentary. As the script developed, the material divided itself naturally into two 45- minute sections.

Part One: The First Called tells of the often turbulent events that swirled through Mrs. Eddy’s homes during the founding of Christian Science as an organized church and movement — in the face of growing hostility and aggressive opposition. The turmoil and triumphs of the 1880s and 1890s included: Mrs. Eddy’s teaching of a small army of students in Boston; her moving to greater seclusion in Concord, New Hampshire, first in a rented home and then at Pleasant View; revising the 50th edition of the textbook; restructuring The Mother Church and building its first church edifice, against many forms of resistance; publishing the first edition of the Church Manual; directing the organizational steps of 1898; and, from 1899 to 1901, meeting the challenge of the Woodbury law suit.5

In Part Two: “I Now Call Soldiers,” the story continues from 1901 to 1903, but this section focuses less on events than on the quality of life as it was lived at Pleasant View. Those in the household were there for more than taking dictation, driving the carriage, serving meals, sweeping the rugs, or keeping her pencils sharpened. They were there to stand their ground, watching and working at their Leader’s direction through the storms and struggles that attended everything she did. She told one of her recruiters to find someone who would stand.6

Eyewitnesses to History: Sources and Selectivity

The best way to tell that story is through the actual words of eyewitnesses who left us a record of what they saw, heard, and did. The film pieces together their accounts to give an intimate perspective on what it meant to be called to duty at the very center of the battle.

The accounts are preserved in reminiscences by some of those who served in the household.7 Although written much later, these recollections, with details of their daily lives working for Mrs. Eddy, have great immediacy. We were mindful that such reminiscences, like all documental sources, must be scrutinized for reliability, objectivity, historical context, and each writer’s personal point of view. Searching very selectively, we pored through reminiscences, letters, diaries, and mementos of the household workers; through Mrs. Eddy’s own letters and other writings; and through biographies by authors such as Sybil Wilbur, Irving Tomlinson, Judge Clifford Smith, and more recent ones like those by Robert Peel and Stephen Gottschalk.

What we looked for are those little stories that help bring the larger story to life. The idea in a documentary is to tell what occurred and let viewers find their own meaning and significance in those events. What’s wanted are straightforward accounts of what happened — reportage rather than rhapsody.

Not all that happened at Pleasant View was deeply serious. Amusing moments at Pleasant View do pop up in our film, and audiences have found them enjoyable as well as revealing. However, this is one movie whose purpose is not amusement or sentimental escapism, but education. Knowing the facts about how Mrs. Eddy and her household practiced Christian Science in their day-to-day work is historically instructive. It’s also inspirational. Knowing more about Mrs. Eddy will, hopefully, inspire viewers to reread and study her published writings on which she worked so tirelessly.

Also, knowing the facts is essential to clearing away myths about Mrs. Eddy. And there are plenty of them! For just one small example, there’s the notion that Mrs. Eddy was not one to run her life by the clock. In fact, Mrs. Eddy did keep her eye on the time. She had three or four clocks in her study. She had a clock on the table beside her bed. She even had an illuminated clock in the sitting room (also known as the “swing room”) where she relaxed at the end of the day. (Furnishing our replicas of the Pleasant View rooms required our set decorator to go on a far-and-wide clock search!) Like everything in the film, all those clocks are there because they show us something meaningful. Mrs. Eddy set aside for herself specific times for prayer. When she went to her desk in the morning, she opened her Bible seemingly at random (but actually with a prayer for guidance), read the first verses her eyes lit upon, and worked prayerfully with that passage for a period of time. Then she turned to her morning’s work. At 11:00 A.M. on the dot, she set her work aside and went on the back veranda for an hour to “talk to God,” as she told her household.8 Systematically structuring her day hour by hour assured she would have the times for prayer that were essential to maintaining her mission.

What Kind of Documentary to Tell This Story?

“Who Shall Be Called?” uses a documentary format in which a narrative is illustrated by photos, documents, and artifacts of the period, and by scenes staged with historical accuracy. Such scenes are created with great restraint. There is no fictionalized dialogue. In fact, there is no dialogue at all. Faces of the principals are not seen. Individuals are represented by gestures and other details that simply illustrate the words. This format was also the one selected for Longyear’s previous documentaries, The Onward and Upward Chain and “Remember the Days of Old.”

What the viewer takes away from this kind of documentary comes more from what is heard than from what is seen. Words and voices come first; pictures and scenes, second. Events are described by two objective, journalistic narrators — a man and a woman — who recount what people said and did.

The words of the narrative are interspersed with the words of people who were there, excerpted from their reminiscences and other documents. These men and women tell stories about themselves — where they came from, what brought Christian Science into their lives, and what brought them into the life of the Leader of Christian Science. The speaking style adopted for each member of the household is in character with his or her words. A distinctive, down-toearth voice speaks for the dutiful midwestern cook, Minnie Weygandt. A very different voice represents the crisp English accent of Mrs. Eddy’s sympathetic young personal maid, Adelaide Still. There is the rugged tone of the groundskeeper, second-generation German-American farmer John Salchow. John Lathrop, the young Christian Science practitioner from New York, is given a more polished diction, as is Clara Shannon, a former concert singer from Montreal who had become a practitioner and teacher.

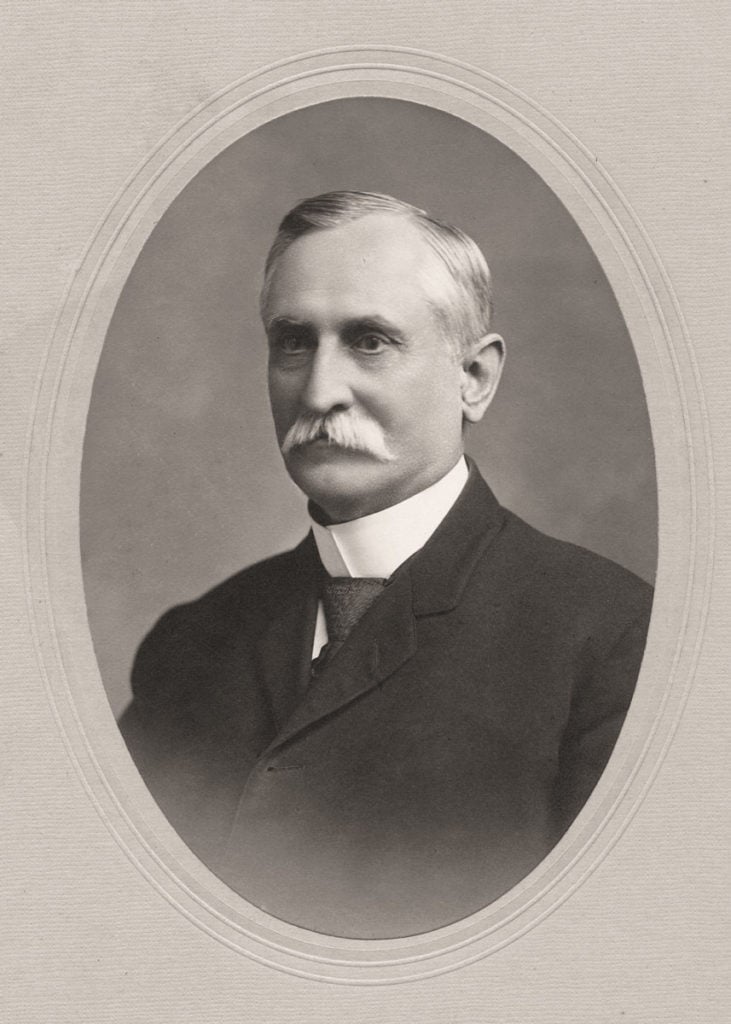

Then there is the Yankee twang of Calvin Frye, the machinist from the mill town of Lawrence, Massachusetts — a man of few words but deep feelings, who answered Mrs. Eddy’s call in 1882. Honest, faithful, sometimes blundering, Calvin was the man who came early and stayed late, devoting nearly thirty years to serving his Leader and her Cause. One of the things we hope viewers will take away from this film is a warm feeling for this self-effacing common man to whom the Christian Science movement owes so much.

What about a voice speaking for Mrs. Eddy? At one time Alfred Farlow, Manager of the Committee on Publication, suggested to Mrs. Eddy that she record something for posterity on Mr. Edison’s new “talking machine.” She declined. She said she could not imagine why anyone would care to hear the sound of her voice. Reminiscences and descriptions in the press indicate that Mary Baker Eddy was lively, animated, showed her feelings, spoke clearly, vigorously, sometimes tartly, sometimes with deep emotion and affection. Beyond such descriptions, no one knows exactly what she sounded like. So the film avoids imagining or dramatizing her voice. Instead, the woman narrator quotes what Mrs. Eddy wrote or said, reporting her words and their context, but not impersonating her.

“Rhythm of Head and Heart”

“Who Shall Be Called?” is not a dry recounting of facts and dates. The story it tells is a deeply moving one. Its spiritual and emotional sweep is expressed in flowing music composed especially for this film. Some segments use melodies of well-known hymns. As each familiar tune is heard, even when the words are not sung, they echo in the mind’s ear, appealing to “head and heart.”9

The saga of constructing the original Mother Church edifice is accompanied by the forceful melody of a hymn that brings to mind the hymn’s equally forceful words: “Long hast thou stood, O church of God.”10

Workers are gathered to “man the fort” at Pleasant View to the marching cadence of another familiar hymn, evoking Violet Hay’s stirring lyrics about service to God: “I love Thy way of freedom, Lord, To serve Thee is my choice.”11

Mrs. Eddy’s fledgling church, meeting on camp stools in her parlor on Broad Street, Lynn, is recalled by Calvin Frye to the strains of one ofMrs. Eddy’s favorite old revival hymns: “I love to tell the story…”12 In this case the words are sung.

Members of the Longyear Board of Trustees and staff rendered some four-part harmony to recreate the sound of the little congregation in 1881.

And there’s the brass band! The film opens in 1901, as Mrs. Eddy arrives at the New Hampshire State Fair in Concord. According to news clippings, the band greeted her with the sprightly Civil War era march, Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean. Our composer found us a high school music director who prepared sheet music arrangements and conducted his own ensemble for this documentary. So the sequence opens with the peppy gusto of an outdoor bandstand, conveying the boisterous welcome Concord gave its celebrity citizen.

Rosy vs. Real

Many Christian Scientists over the years have had an impossibly rosy image of what it was like to serve in Mrs. Eddy’s home. For those who actually served there, day-to-day life was neither a bed of roses nor an endless campaign of wars and rumors of war. There were moments of each.

The film shows both sides of this balance. On the one hand, Calvin Frye recalls being sharply criticized by Mrs. Eddy, and Adelaide Still tells of his being soundly put in his place when he argued his own point of view over his Leader’s. On the other hand, another household member recounts Mrs. Eddy’s comment that Calvin was invaluable to her because he “would not break one of the Ten Commandments.”13 And Adelaide tells of calm, glowing moments at the end of the day with Calvin and Mrs. Eddy chatting and enjoying the sunset in her swing room.

In the swing room a battery-powered light bulb had been arranged to illuminate the face of a little clock so that, even in the gathering dusk, the ever-punctual Mrs. Eddy could mark the hour. Calvin, always protective of his Leader, used his skills as a former machinist to solder a tiny metal shade, so the bare bulb would not shine in her eyes. In recreating Mrs. Eddy’s beloved swing room, we replicated the battery box and Calvin’s shade. It’s a minor detail, but not a trivial one, because it tells us much about the relationship between these long-time comrades-in-arms.

For all such peaceful moments, working in this household could be a trial at times. Mrs. Eddy was kind, thoughtful, warmhearted, sometimes lighthearted, and deeply concerned for all her staff. She was also hardworking, devout, punctual, punctilious, richly inspired, and always alert to whatever challenged her Cause. She demanded of her staff, as she demanded of herself, that they live up to the highest standard of Christian Science practice. They had to, for their own good and for hers. She admonished them severely when they failed to measure up to the metaphysical needs of the hour.

In our documentary, John Lathrop tells how Mrs. Eddy sternly called him on the carpet one day for neglecting the metaphysical work she had asked him to do. John did not count this discipline an unreasonable hardship. He was glad to be corrected. Those who were not glad to be corrected by Mrs. Eddy did not last long under her roof. But the band of faithful workers who stood their ground with her were happy, in fact, honored, to be called on to meet what was demanded of them. Mrs. Eddy described them in a notice published in The Christian Science Journal: “The world is better for this happy group of Christian Scientists;Mrs. Eddy is happier because of them; God is glorified in His reflection of peace, love, joy.”14

What enabled these workers to persevere in this arduous calling? In an interview with author Robert Peel, Adelaide Still described some events that were difficult for her when she served as Mrs. Eddy’s personal maid. Peel asked her, “Adelaide, didn’t you ever resent or rebel at the demands Mrs. Eddy put on you?” Adelaide drew herself up. “Why, no!” she told him. “This was the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science!”15 Such conviction, along with a willingness to strive and attain spiritually were the qualities that determined who should be “called to Pleasant View” — and who would stay the course.