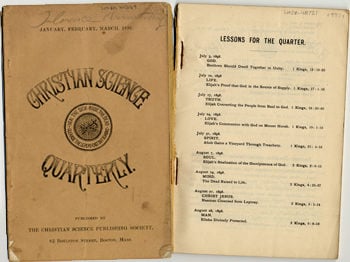

One hundred years ago this September “…at the request of Rev. Mary Baker Eddy, twelve of her students and Church members met and reorganized, under her jurisdiction, the Christian Science Church and named it, THE FIRST CHURCH OF CHRIST, SCIENTIST.”1 She had previously indicated the pattern that this reorganization would follow in an article for the July 1892 edition of The Christian Science Journal. In that article titled “Hints for History” she reminded her followers of “The diviner claim and means for upbuilding the Church of Christ…” and cautioned them to “…let the divine will and the nobility of human meekness, rule this business transaction in obedience to the law of God, and the laws of our land.” It is the purpose of this issue of Quarterly News to provide our readers with an historical review of key events relative to this momentous organizational redirection of the Christian Science Church that would, eventually, ultimate in the publication of the Manual of the Mother Church.

The need to disorganize

The very difficulties attendant upon the congregational style of church government that had grown up around the 1879 charter2 for the Church of Christ, Scientist, made clear to Mrs. Eddy, in the late 1880s, the need to move her church forward organizationally.3 Although the Christian Scientist Association had approved Mrs. Eddy’s non-traditional motion in April 1879 “To organize a church designed to commemorate the word and works of our Master…; they nonetheless followed the familiar patterns for Protestant church organization, which included personal preaching and a congregational style of church government.4 Such organization might be adequate for a localized church, but not for a church conceived of as “…imperatively propelling the greatest moral, physical, civil, and religious reform ever known on earth.”5 In 1888, moreover, both factionalism and rebellion threatened to destroy the young Christian Science Church in Boston.6 By late November 1889, in a letter to a student7 Mrs. Eddy gave unmistakable direction as to the type of organizational structure necessary for the survival of her church. In that letter she exemplifies the same unwavering trust, so characteristic of her healing works, in relation to the transformation of her church, in these words: “This Mother Church must disorganize, and now is the time to do it and form no new organization but the spiritual one.”8

The end of the 1879 church organization

To use an architectural metaphor, the disorganization of the church could be likened to the thorough renovation of a building, in which the basic frame remains intact, but its interior features are removed so that the space may be reconfigured to better fit its purpose. Following Mrs. Eddy’s instructions in early December 1889, the members voted to dissolve the church organization. This change did not mean the termination of the church or its activities. In fact, the 1879 church charter was never surrendered9 nor did church services cease. The church continued on as a sort of voluntary religious association with a valid corporate charter. What had changed was that, in dissolving the church organization that had grown up around the 1879 corporate charter, the Boston church had begun to free itself from some of the limitations of a congregational form of church polity in which the entire membership directs, by vote, the major functions of the church.10 Mrs. Eddy’s disorganization of the Boston church in December 1889 did not mean the utter rejection of organizational structure for her church.11 Rather than the outright destruction of the body corporate, her writings from this period illustrate her conviction of seeking the healing and restoration of her church on “…the purely Christly method of teaching and preaching….”12 Writing only two years after the decision to disorganize her church and referring to those very changes, she could say, “After this experience and the Divine purpose is fulfilled in these changing scenes, this church may find it wisdom to organize a second time for the completion of its history.”13

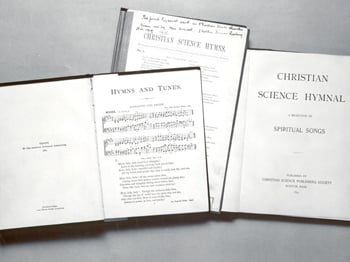

The period from the disorganization of the church in 1889 to its reorganization some three years later was a time rich in foundational developments for the Christian Science movement, including the landmark fiftieth edition of Science and Health in January 1891 and the first edition of Retrospection and Introspection in November 1891.14 Clearly, it was Mrs. Eddy’s own initiative under God’s impulsion that was guiding her into this new uncharted territory of developing an organizational structure that would most nearly approximate what she perceived as the spiritual basis of church, even as her successive revisions of Science and Health sought word structures that would more precise! y express her “…glimpse of the great fact…Life in and of Spirit….”15

Seeking a method for reorganization

How to fashion a human organization that would serve the unique requirements of a church dedicated to the “…apprehension of spiritual ideas…”16 gradually became evident to Mrs. Eddy over a period of more than thirty years. This gradual development of the church organization was even recognized by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in a 1924 decision that read in part, “Her views in 1892 apparently were in a state of transition, development or evolution. She had not then completely formulated the precise form of ecclesiastical organization best adapted in her mind to carry out her conception of a church. She was studying the problem but had not reached a conclusion.”17

To attach undue concern to the extent that the years from 1889 to 1892 and after can be characterized as a state of organizational transition is to miss the crucial point of Mrs. Eddy’s unwavering conviction that, “…material ways and means whereby to establish the Church of Christ are weak….”18 On the surface, much of the controversy in 1892 appeared to be related to such things as the question of who had the legal authority necessary to enable the Boston congregation to proceed with the building of a church edifice or a combined church and publishing building. Yet the real controversy in that period was the age-old conflict between man’s knowledge and God’s wisdom.19

Finding the right method for reorganization

In the early spring of 1892, Mrs. Eddy wrote a letter to the Christian Science Church in Denver, Colorado, at the time of the dedication of their new edifice, reminding them to, “Exercise more faith in God and His spiritual means and methods, than in man and his material ways and means of establishing the Cause of Christian Science.”20 The result of her “exercise of faith in God and His spiritual means and methods…” became evident in August 1892. As Mrs. Eddy put it in October 1892, “About six weeks ago I called for legal counsel and engaged two able lawyers in my native state. Guided by the Divine Love they found in the laws of Massachusetts the statute…for incorporating a body of donees, without organizing a church. Truly, God’s ways are not man’s ways; and faith in the Divine methods are indeed the footsteps of the flock. What joy might now crown this faith had it taken firmly the first steps and held on, till it clasped God’s right hand.”21

The statute “…for incorporating a body of donees…” allowed for the creation of a governing board for her church that could handle both the fiduciary and the religious responsibilities she would assign to them. As section one of Chapter thirty-nine of the Massachusetts Public Laws states, “The deacons, church wardens, or other similar officers of churches or other religious societies, and the trustees of the Methodist Episcopal churches, appointed according to the discipline and usage thereof, shall, if citizens of this commonwealth, be deemed bodies corporate for the purpose of taking and holding in succession all grants and donations, whether of real or personal estate, made either to them and their successors, or to their respective churches, or to the poor of their churches.”22 Prior to the establishment of the Christian Science Board of Directors as “…a perpetual body or corporation under and in accordance with section one, Chapter 39 of the Public Statutes of Massachusetts”23 on September 1, 1892, Mrs. Eddy requested twelve of her students to meet on August 29th to organize a corporation to be known as “The First Church of Christ, Scientist.”

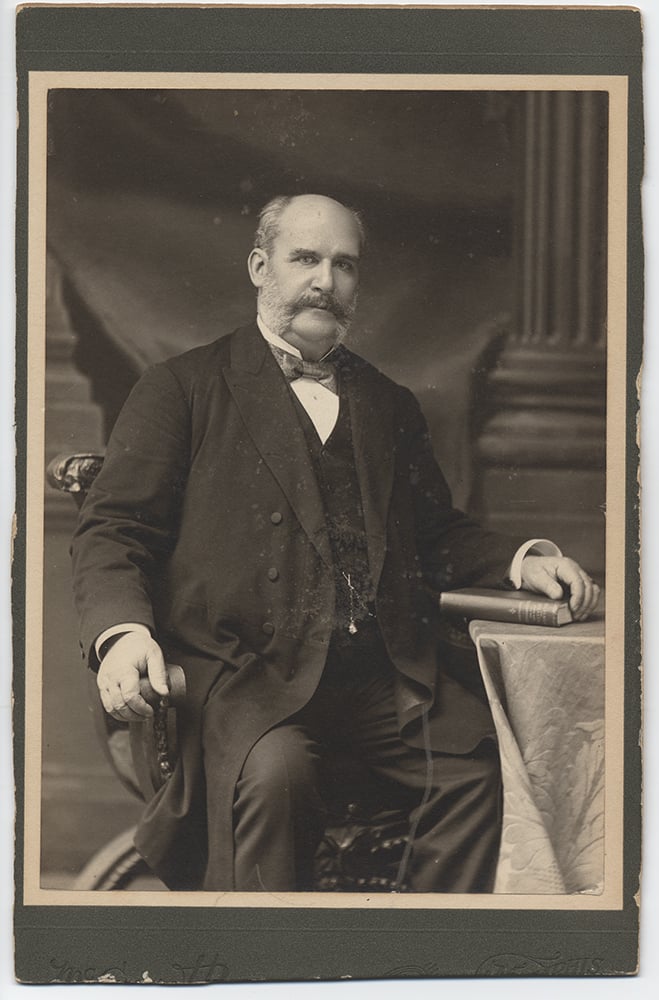

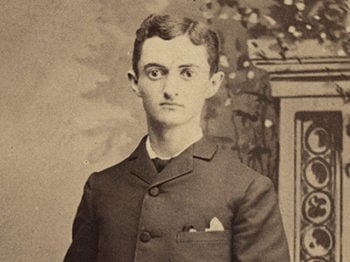

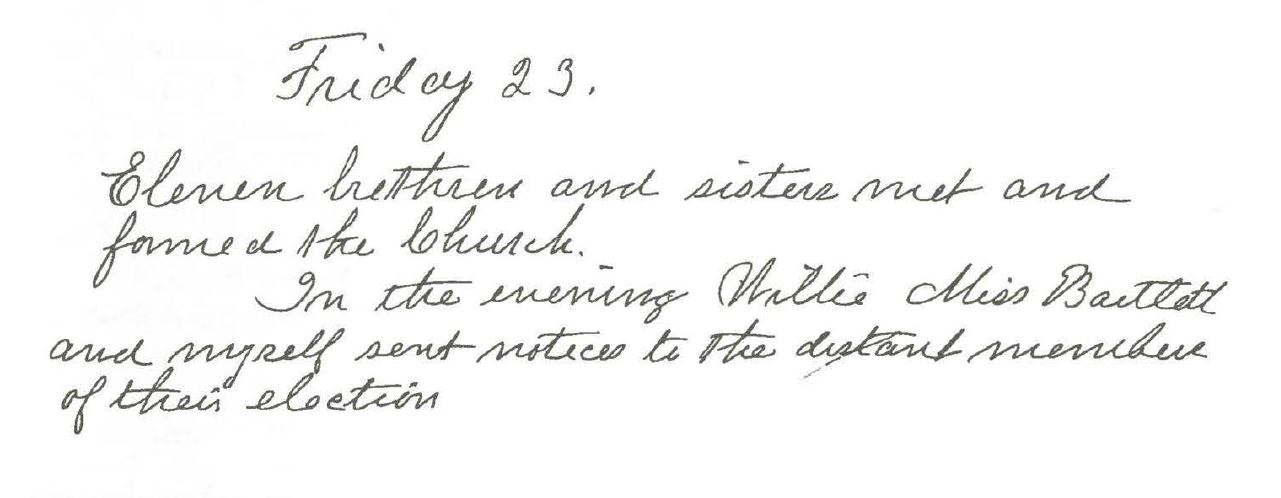

The twelve (Ira O. Knapp, William B. Johnson, Joseph S. Eastaman, Stephen A. Chase, Julia S. Bartlett, Ellen L. Clarke, Janet T. Colman, Mary F. Eastaman, Ebenezer J. Foster Eddy, Eldora O. Gragg, Flavia S. Knapp, and Mary W. Munroe)24 met at Julia Bartlett’s rooms on Dartmouth Street in Boston.25 At the August 29th meeting the twelve were informed by a message from Mrs. Eddy, sent via Ebenezer J. Foster Eddy, that a new church corporation would not be formed. Instead these faithful students were acquainted with and concurred in support for a new deed of trust drafted by Mrs. Eddy that made use of the Massachusetts statute previously mentioned, which allowed for the creation of “…a perpetual body or corporation…” to “be known as the ‘Christian Science Board of Directors.'” This deed of trust revised the church’s name from its 1879 title as “Church of Christ, Scientist” to “The First Church of Christ, Scientist.” Principally, the deed of trust, executed on September 1, 1892, served to convey title for the land on which the original edifice of the Mother Church was to be built from Mrs. Eddy to the Christian Science Board of Directors.26 As one biographer of Mrs. Eddy has aptly noted, this deed of trust, “…has always and very justly been looked upon as one of the important landmarks in the history of the movement, for in it the plans for a ‘Mother Church,’ which Mrs. Eddy had evidently been formulating for some time, were first unfolded.”27

The newly organized Christian Science Board of Directors included Ira O. Knapp, William B. Johnson, Joseph S. Eastaman and Stephen A. Chase.28 On September 16, 1892, Knapp, Johnson, Eastaman and Chase sent a letter to all contributors to the church building fund to apprise them of the current situation. In that letter they informed the contributors that the Christian Science Board of Directors was now formally organized (under Massachusetts corporate law), held legal title to the land upon which the church edifice would be built and was legally empowered to collect and hold funds for building the church.29