Boston, Massachusetts, June 28, 1903: Sallie Loughridge of Fort Worth, Texas, stood before Mechanics Hall Building on Huntington Avenue, Boston, where The Mother Church would hold three Communion services that day. Sixteen years earlier a friend had urged her to turn to Christian Science. For years she had suffered from a fibroid tumor weighing “not less than fifty pounds, attended by a continuous hemorrhage for eleven years.”

Obtaining a copy of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy, Miss Loughridge studied the book, exclaiming aloud at what she was reading. One day she realized that she was well. The tumor “began to disappear at once, the hemorrhage ceased, and perfect strength was manifest.”1

Five years later, Miss Loughridge joined The Mother Church, in 1893. And now on a fine June day in 1903, she was in Boston to attend Communion in The Mother Church. The edifice of The Mother Church, dedicated eight years earlier, was not large enough to accommodate the worshippers, and so the services were held at nearby Mechanics Hall Building.

Since the previous Thursday morning Mechanics Hall had been abuzz, from nine in the morning till nine at night, staffed by Christian Scientists who answered visitors’ questions, gave directions, issued membership cards for admission to special meetings, and coordinated discounted fares offered by railroad and steamer lines. For a week, right up through Wednesday evening, Mechanics Hall remained the hub of information, twelve hours a day.

At seven-thirty on Communion morning, the doors of Mechanics Hall were opened, and seventy-five ushers snapped to attention. By eight-thirty, the main floor and balcony were full. The service began at nine o’clock, and at its close, the auditorium was cleared, and those waiting for the eleven-thirty service were admitted. There was a third service at two o’clock.

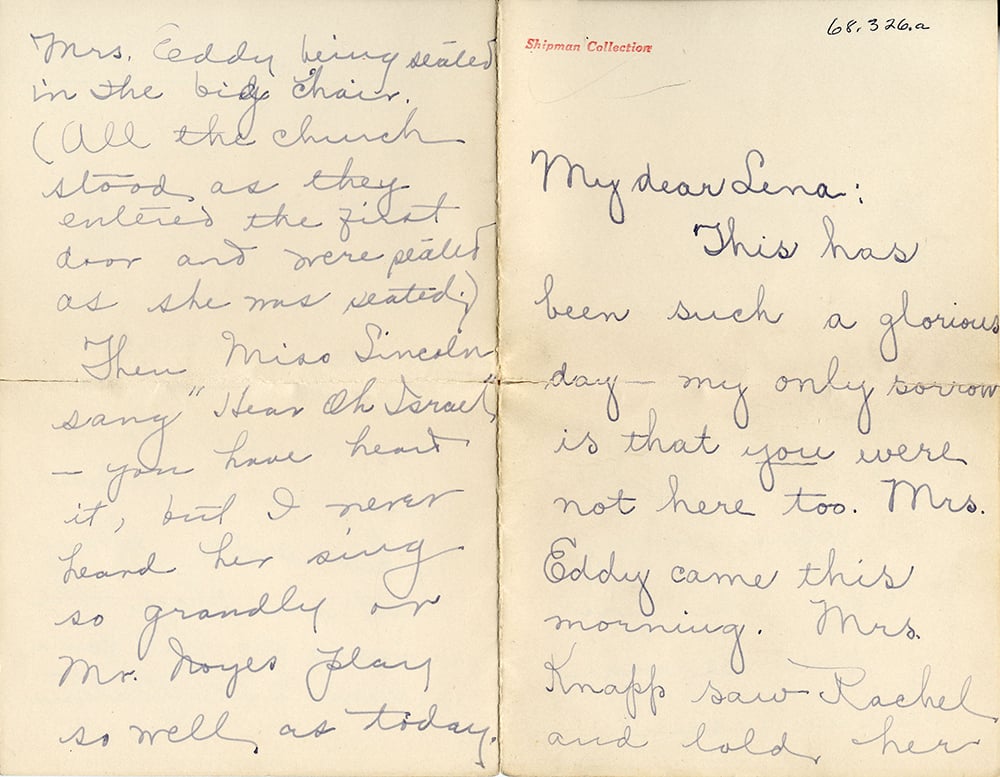

Events of the Communion season deeply impressed Sallie Loughridge, impelling her to record:

The Communion season which has just passed, the visit by invitation to our beloved Leader’s home, and, last but not least, her letter and words of love, have stirred my heart to its depths and I want to say, Dear God, make me, make us all, indeed thankful for these thy blessings.2

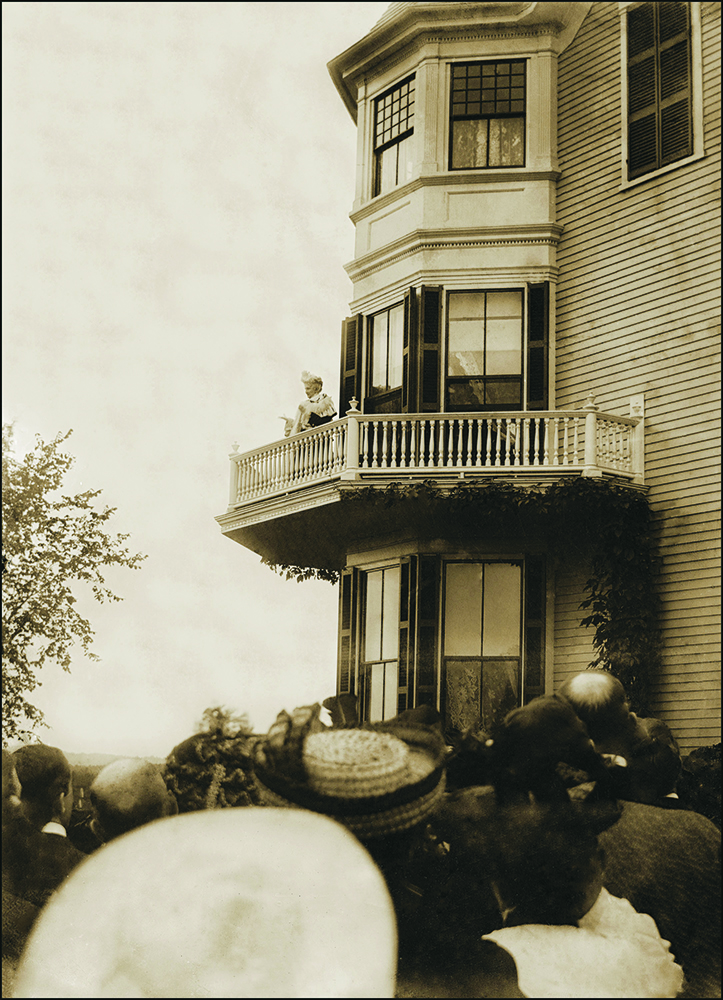

Since the late 1890s, the Communion season had included more than the Communion service itself. The day after Communion, visiting Christian Scientists frequently went seventy miles north to Mrs. Eddy’s home, Pleasant View, in Concord, New Hampshire. In 1903, Mrs. Eddy’s invitation was announced at the Communion service, and in less than twenty-four hours travel arrangements were made and tickets printed to convey ten thousand people to Concord. The Boston Evening News commended the orderliness, noting that “not even a railroad official lost his temper.”3

On Tuesday afternoon, Annual Meeting would be held. And there would almost certainly be another message or letter from Mrs. Eddy on that occasion as well.

On Wednesday there was sure to be a memorable testimony meeting, with testifiers from around the world. In 1903, visitors came from as far away as Australia, Italy, Germany, the United Kingdom. Occasionally over-enthusiastic members held impromptu testimony meetings in hotel lobbies, a practice which the editor of the Christian Science periodicals reminded them was discourteous to other hotel guests and should be discontinued.4

The Communion service in Christian Science worship was simple. Communion season, on the other hand, involved quite a bit more.

“To kneel with us”

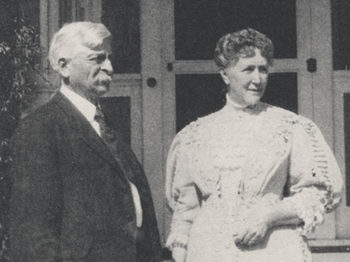

Addressing ten thousand visitors at her home the day after the 1903 Communion, Mary Baker Eddy noted that some had “come long distances to kneel with us in sacred silence in blest communion.”5

Kneeling and silence — two words that describe, at least outwardly, Christian Science Communion services. During the 1880s, it was the pastor, not the congregation, who kneeled. The Christian Science Journal provides two depictions of Mary Baker Eddy kneeling as she conducted Communion services:

After a short statement of the spiritual intent of the eucharist, the congregation sat in silence, while the pastor knelt in silent prayer.6

[After singing the hymn “On the night of that last supper”] came the sublimely simple, spiritual Communion of Christian Science; the Pastor kneeling at her chair, and leading the desires of all who communed with her in Spirit, as, in this supreme act of worship, they bowed “before Christ, Truth, to receive…more of his reappearing, and silently communed with the divine Principle thereof.”7

In 1892 congregational kneeling was a definite feature of Mrs. Eddy’s order of service following the “Invitation to Christ’s Table”:

Communion: Pastor and Church kneel (and all who love our Communion) silently partaking of the Bread which cometh down from Heaven, and taking the Cup of Salvation.8

The historical evidence, though scanty, points to the absence of kneeling by the congregation during the 1880s and to Mrs. Eddy’s adding it to the service in 1892.9

“Expressive silence”

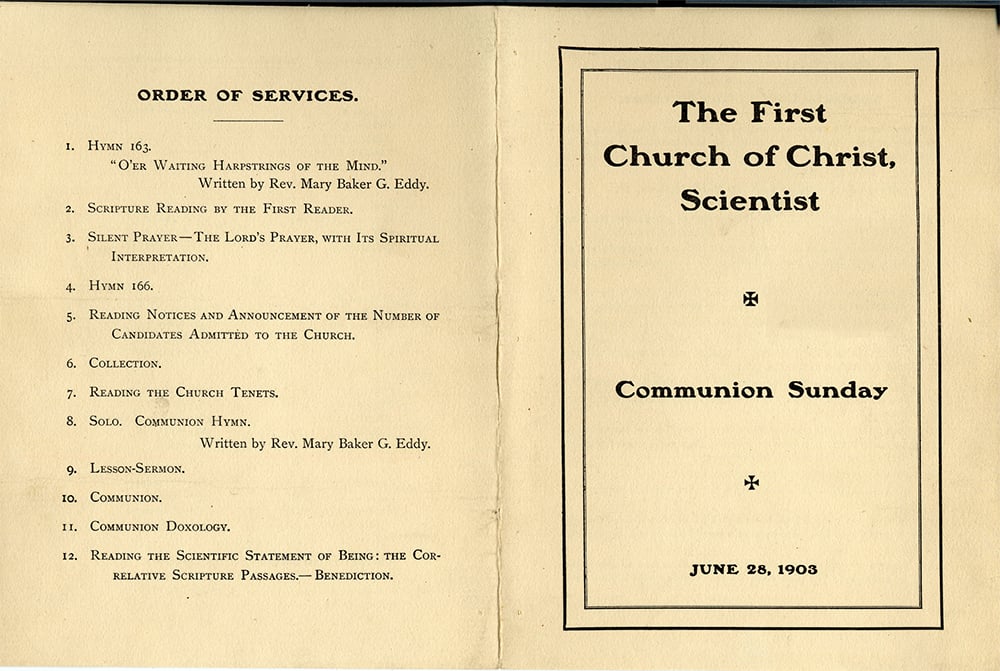

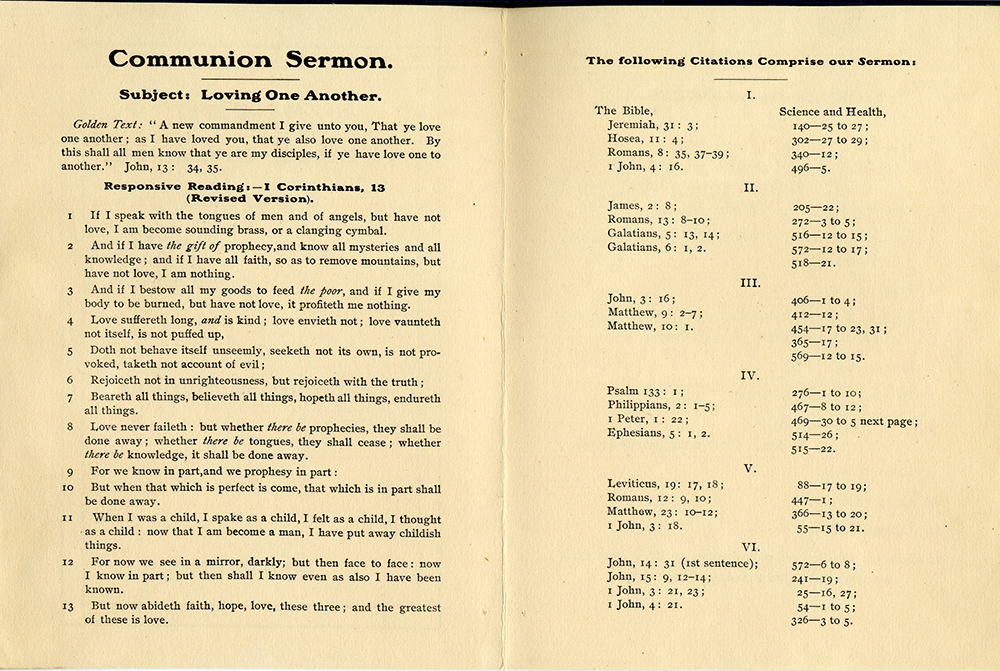

At the 1903 Communion service, the Communion sermon, “Loving One Another,” had just been read and First Reader Hermann Hering announced: “I now invite all present whether members of this church or not, to unite with us in spiritual, holy communion with the one God, infinite Love.”

The congregation knelt in silence. Profound silence. As the Boston Herald had described the service several years before:

No material elements lay upon the altar, no bread nor wine passed from hand to hand and lip to lip. With bowed head and bended knee, and in a silence so profound that it seemed itself to proclaim the resolving of substance into spirit, the multitude…received the spiritual sacrament for which they had come so far.10

“We have not before us a cup of wine or a broken loaf to commemorate the Life of our Lord,”Mrs. Eddy told a congregation in the 1880s, adding, “Bread and wine stand for ideas”:

They express and suggest spiritual thoughts that we should entertain without any material symbols, and who but our Master could discharge so well the office of their interpreter. Would that I could impart half as well the new and vivid sense of the greatness and truth of that faith and Love of which they tell, and you would catch the inspiration….Then you would understand the science of divinity and know what it is to commemorate Jesus in spirit and in Truth.11

When addressing The Mother Church at Communion in 1896, she called the congregation’s attention to “expressive silence”:

It is well that Christian Science has taken expressive silence wherein to muse His praise, to kiss the feet of Jesus, adore the white Christ, and stretch out our arms to God.12

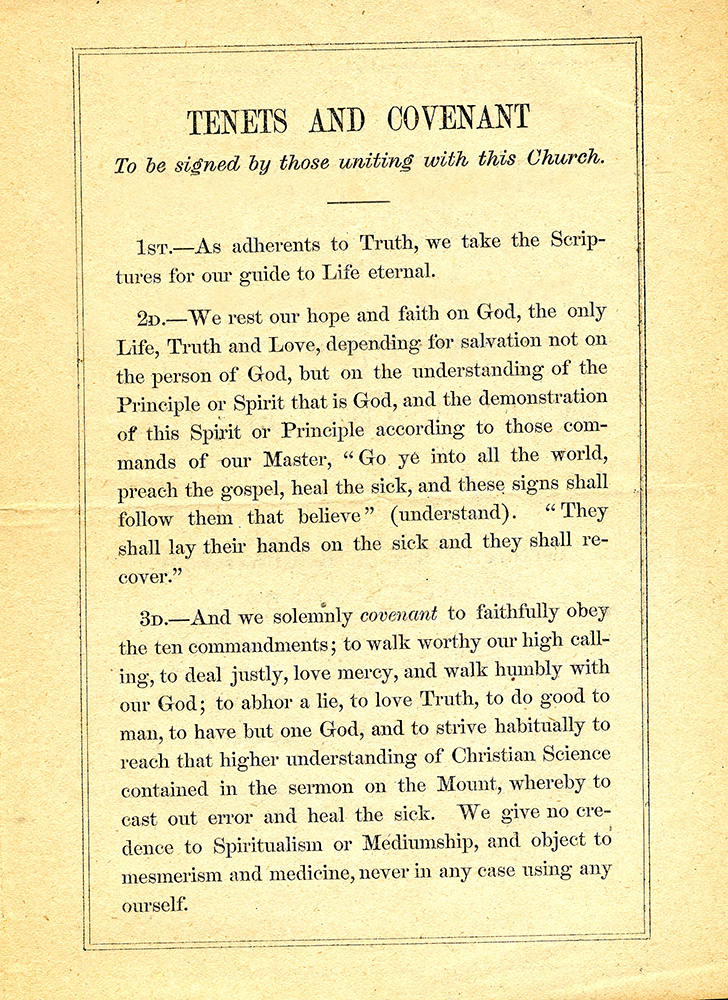

Here, then, would emerge a new dedication to sharing the bread and wine of Christ’s table, realized not through the literal symbols but through “expressive silence.” The bylaws of Mrs. Eddy’s first church organization set forth its nature (see sidebar “ ‘Solemn and silent self-examination’ ”).

The right hand of fellowship

“On the sacramental Sabbath,” state the first bylaws of the church, “the Articles of the Church [that is, the Tenets] shall be read in the presence of the congregation to those who are to be received, to which the candidates shall signify their consent.”13 The bylaws also required candidates to sign their names to the Tenets. Thus, reading the Tenets on Communion Sunday and candidates’ signing their names to the Tenets can be traced to the earliest days of the church.14

Even as Mrs. Eddy, when preaching on Communion Sundays in the 1880s, would explain silent Communion, she would also instruct the candidates on the solemnity of joining the church — thereby reminding the whole congregation of the significance of membership. The Journal recounts a Communion in March 1886:

Thirty-three men and women stood up and were received into church-membership, Mrs. Eddy making a short address, and reading to them the brief articles of faith.15

After the candidates had given their assent to the Tenets, Mrs. Eddy extended to them “the right hand of fellowship.” This gesture of unity in Christly purpose reaches back to that momentous meeting in early Christian history when James, Peter, and John extended their “right hands of fellowship” to Paul and Barnabas, thus recognizing the spiritual authenticity of their ministry to the Gentile world.16

Mrs. Eddy’s charge to new members made lasting impressions. A woman who joined the church in the 1880s recalled, “Well do I remember the Mother’s [Mrs. Eddy’s] counsel as she extended to each the right hand of fellowship.”17

After the new members had been welcomed, Mrs. Eddy invited the worshippers to join in silent Communion. At one such service she said:

We welcome you to the table of our Lord; and beg that you come with due consideration of the magnitude of Christianity, its self-renunciation, heaven born hope, spiritual faith, God-guided understanding, purity, truth and Love.

Come thou to the Church of the new born as a little child — take hold of the hand of Jesus, obey his commands, follow his example, study the scriptures, and thou shalt go from strength to strength until thou arrive at the fullness of stature, for he hath said Lo! I am with thee alway even unto the end.18

At the church’s first Communion, January 4, 1880, just two members were admitted. The regular business meeting held two days earlier “for deliberation before Communion Sabbath was rather sorrowful; yet there was a feeling of trust in the great Father, of Love prevailing over the apparently discouraging outlook of the Church of Christ.”19

The “trust in the great Father” over the years was evident: twenty-three years later at the June 1903 Communion season 2,695 new members were admitted.20 By this time, the number of new members at each Communion was so large that the practice of reading each name was replaced by announcing the number of new members.

Before that change, however, the requirement of reading the names caused the date of a notable Communion Sunday to be moved up by one week: The dedication of the Original Edifice of The Mother Church — January 6, 1895 — was to have been a Communion Sunday. When it was realized that reading the names of 560 new members at each of the four services (one of them exclusively for children) would occupy too much time, Mrs. Eddy allowed Communion to be observed a week earlier, on December 30, 1894.

Thus the first service in the Original Edifice was a Communion service, and the first hymn sung there was Mrs. Eddy’s poem, “Communion Hymn.”

At this service Judge Septimus J. Hanna, who had been pastor for ten months, announced Mrs. Eddy’s directive that beginning with that Sunday the Bible and Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures were to be the pastor of The Mother Church. Three months later, she ordained this “dual and impersonal pastor”21 as pastor of the branch churches as well.22