“As a young man, my family knew people who’d known Mary Baker Eddy,” former Longyear trustee Graves Hewitt recalled in the late 1990s, ticking off such names as William Rathvon, who had served in Mrs. Eddy’s household, and William Dana Orcutt, her publisher, whom Mr. Hewitt’s parents had entertained in their home. “It wasn’t until sometime later that I realized what an extreme privilege I’d had and which I had not appreciated fully at the time.”1

As part of the last generation with a personal connection to these early Christian Scientists, Mr. Hewitt also realized that he and others like him, including a number of his fellow trustees, owed it to future generations—those who would be even further removed from Mrs. Eddy’s day—to help tell her story in an accurate and compelling way. For him, this was where Longyear Museum came in. Long before he became a trustee, Mr. Hewitt was a visitor, one who appreciated the unique collection of artifacts, reminiscences, portraits, photographs, letters, historic houses, and more, that shed light on Mrs. Eddy’s spiritual journey.

The desire to help preserve the evidence of Mrs. Eddy’s life for individuals like Mr. Hewitt was what spurred Mary Beecher Longyear into action decades earlier. In early January 1923, she wrote in her diary:

“The most important thing in the whole world at this time, seems to me, is the preserving of the incidents and the authenticity of the history of the life of Mary Baker Eddy. How few … at the present time realize the great necessity of keeping the records of her early life….”2

Two weeks after penning these prescient words, Mrs. Longyear took a step that would send ripples down the century to come. On January 18, 1923, she created a deed of trust establishing the Longyear Foundation.3 Its mandate was to preserve, protect, and make available to the public the collection she had begun to gather related to Mrs. Eddy’s life and work. The document formalized her efforts, providing the means and direction to safeguard the artifacts for the future.

The collection had begun informally in late 1917, when Mrs. Longyear was struck by Mrs. Eddy’s statement, “Christian Science and Christian Scientists will, must, have a history….”4 The very next day, she paid a visit to Janet Colman, one of Mrs. Eddy’s early students, who heard Mrs. Longyear out and subsequently donated a photograph of herself. The following week, Mrs. Longyear called on three more pioneering Christian Scientists—Julia Bartlett, Mary Eastaman, and Ellen Clark—with similar results. From there, she was off and running as she traveled around the country—often accompanied by her husband, John Munro Longyear, who offered his full financial and moral support—seeking out photographs, reminiscences, letters, and other ephemera from a “cloud of witnesses,” as she called these men and women, echoing the Bible. She would also locate, purchase, and restore a number of homes where Mrs. Eddy once lived and worked. All along, she noted in her diary, “Love seems to open the way.”5

This year, a century after Mrs. Longyear boldly stepped into the world of historic preservation, we find ourselves echoing the words of William B. Johnson, who was serving as Clerk of The Mother Church when he gave a report at the 1906 Annual Meeting that included this statement:

“To-day we look back over the years that have passed since the inception of this great Cause, and we cannot help being touched by each landmark of progress that showed a forward effort into the well-earned joy that is with us now.”6

We invite you to join us as we stroll through the decades and celebrate Longyear’s own landmarks of progress.

1920s

1920–22

Mary Beecher Longyear travels the back roads of New England to find early houses where Mary Baker Eddy lived. In 1920, she purchases homes in Rumney and North Groton, New Hampshire, and in Swampscott, Massachusetts. A fourth house in Amesbury, Massachusetts, is added in 1922.

1921

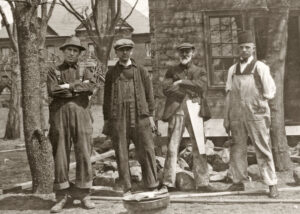

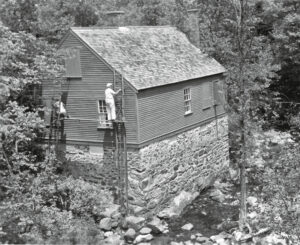

The North Groton house, which had been moved from its original location and had fallen into disrepair, is returned to the site where it stood when Mary and Daniel Patterson lived in it. The contractor in charge, after noting that the sagging roof needed re-framing, writes Mrs. Longyear, “I am trying to locate some old clapboards to match those of the house, for sheathing the outside.”7 When one of the Longyear daughters visits the site and sees scraps of original wallpaper that have been found in a closet, Mrs. Longyear tells the contractor, “I hope they can be preserved.”8 This close attention to detail will become a hallmark of Longyear’s preservation work. Restoration work is also done at Rumney during this year.

1923

On Jan. 18, Mrs. Longyear creates a deed of trust establishing the Longyear Foundation, with the aim of preserving, protecting, and making available to the public the collection she is gathering related to Mary Baker Eddy’s life and work. A Board of Visitors, an entity required of charitable trusts under Massachusetts law, is charged with fiscal oversight as well as ensuring that the founder’s purposes are carried out.9

1923

Mrs. Longyear commissions architect Samuel A. Marx of the Chicago firm Earl H. Reed, Jr., Associated to design a museum to house her growing collection. By September, plans are in hand. There is a grand, two-story central hall for displaying portraits on the first floor and photographs on the second; a spacious gallery devoted to Mrs. Eddy’s life story; and areas for research and study, as well as an “index” room (for cataloguing the collection) and ample storage. Mrs. Longyear’s dream of a purpose-built museum—instead of housing the collection in her 88-room mansion in Brookline, Massachusetts—isn’t a vanity project. She feels “that the upkeep of her residence … would be a tremendous weight on the trustees, and that the use of it for many years to come would not warrant the great expenditure,” note the minutes of a 1925 trustee meeting.10 The Marx plans do not go forward.

1926

Amesbury and Swampscott open their doors. Rumney and North Groton officially open a bit later, although with Mrs. Longyear’s permission, visitors are welcomed unofficially. The monthly salary for the caretaker in Rumney—which doesn’t have indoor plumbing until the late 1930s—is $25.

1926

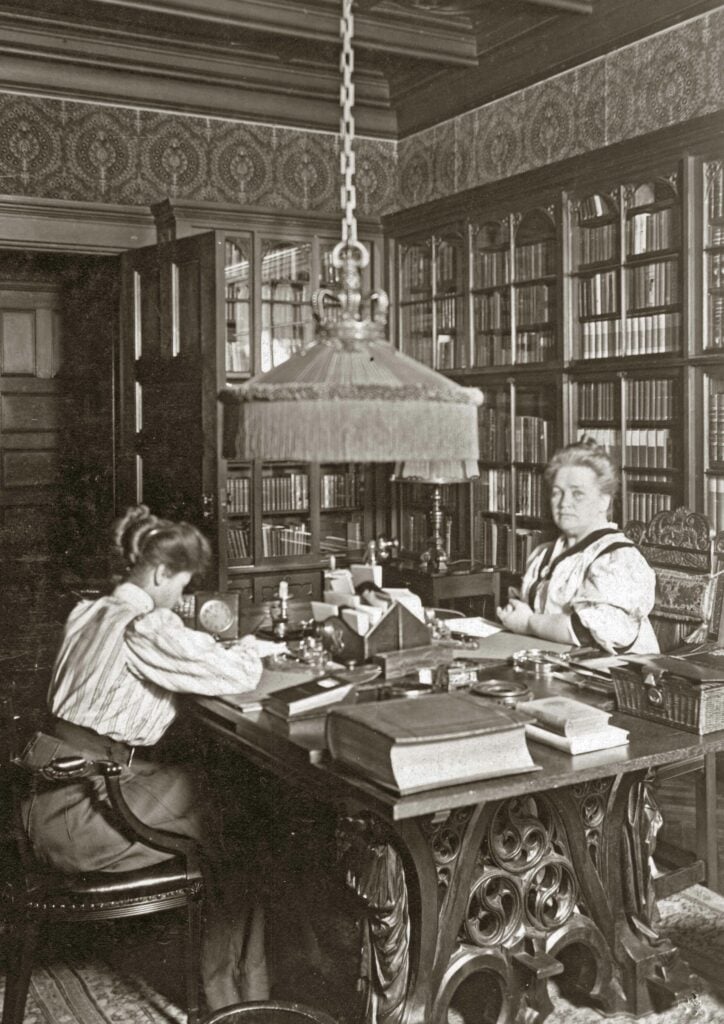

No detail is too small for the attention of the Longyear Foundation trustees. They hire a full-time secretary to support them in their close oversight of the day-to-day operations.

1929

In February, Mrs. Longyear settles on a plan from the Boston architectural firm Gay & Proctor to alter three rooms on the lower floor of her mansion, where she can display her collection. Expenditures on items for the collection (and eventually the October 1929 stock market crash and subsequent economic downturn) dash Mrs. Longyear’s hopes of building a museum during her lifetime. Still, the seed of having a purpose- built museum has been planted.

1930s

1931

On March 14, Mary Beecher Longyear passes on. On April 11, the Longyear trustees offer this tribute, as recorded by their board minutes: “Mrs. Longyear was a woman of great vision and with a tremendous desire to enlighten mankind. … Her friendly association with Mrs. Eddy was a continued inspiration to her and it was her great desire to perpetuate the memory of Mary Baker Eddy as a human being that caused Mrs. Longyear to found this trust. … She felt that Mrs. Eddy belonged to the world, not alone to the church which she founded.”11

Early 1930s

The Longyear trustees begin to consider research requests. Among the researchers are Lyman P. Powell and Judge Clifford P. Smith, whose requests are duly approved. Mr. Powell goes on to write Mary Baker Eddy: A Lifesize Portrait, and Mr. Smith, Historical Sketches from the Life of Mary Baker Eddy and the History of Christian Science.

1933

A second full-time employee is added to help with cataloguing and administrative work.

1934

The Foundation is incorporated in Massachusetts as a nonprofit charitable and educational institution.

1934

Restoration work commences on the Mary Baker Eddy Historic House in Swampscott. The house is painted inside and out, and the interior redecorated. Old furnishings are replaced with items more appropriate to the time when Mrs. Eddy lived there. The Christian Science Board of Directors loans several pieces of furniture for use.12 The Longyear trustees also commission Alma Lutz to write The Birthplace of Christian Science, a history of Mrs. Eddy’s time in Swampscott, which is printed in brochure form to be given to visitors.

1935

On Feb. 1, the Swampscott house opens to much fanfare. The Christian Science Sentinel covers it in its Feb. 23 issue, and The Christian Science Monitor covers it on March 6.13 More than 3,000 visitors will tour the home this year.

1937

The Longyear mansion in Brookline officially opens its doors to the public as a museum. Mrs. Longyear’s concerns that her home would prove a burden turn out to be well founded. “If the property is to be kept permanently, rather large expenditures will be necessary almost immediately,” the trustees tell the Board of Visitors in 1935. “The roof over the old bowling alley, formerly used for the Library reading room, also the roof over the south-west sun porch, are in very bad condition and leaking to such an extent as to damage the plaster and woodwork. The outside trimmings of the house need painting, and all the ironwork, including the fence enclosing the property, needs attention.”14 Underlining the seriousness of their concerns is the fact that the trustees attempt to sell the mansion during this period (asking price $225,000), but “no offers acceptable” are received.15

1940s

1942

In the weeks following the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, the trustees have a new focus: protecting the collection at all costs. At their January 1942 meeting, they consider placing the more valuable artifacts in a bank’s safe deposit vault. In the end, they decide to keep them in the mansion, which “had been judged an excellent, safe place in the event of air raids….”16 Other wartime preparations include: taking out war damage insurance for the mansion and historic houses; installing protective steel shutters over a number of windows at the mansion; converting heating equipment from oil to coal when fuel oil is diverted to the war effort; and purchasing an American flag.

1942

Numerous oil paintings in the collection are found to be in need of repair, including one of its crown jewels, a miniature of George Washington Glover, Mary Baker Eddy’s first husband, and the only known image of him. The miniature is entrusted to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts for restoration at a cost of $25 (about $500 today).

1945

Guides’ salaries at the historic houses are raised from 50 cents to 75 cents an hour.

1948

Exterior of the Mary Baker Eddy Historic House in Amesbury is re-painted; the trustees select “barnyard red, with white trimmings.”17 The house will remain this color until the year 2001, when a paint analysis determines that it was tan with chocolate brown trim during Mrs. Eddy’s day.

1950s

1950

Lively correspondence during this decade reveals glimpses of daily life for caretakers at the Mary Baker Eddy Historic Houses: leaky roofs, clogged drains, peeling paint and other needed repairs, along with a variety of pest control issues, from the two-legged variety (break-ins and minor vandalism by mischievous teenage boys) to the four (mice, moles, and sundry rodents), plus termites, hornets, and other insects. But also clear are the sweet bonds the caretakers share with their colleagues at the mansion. Amesbury caretaker Mabel Lunt, who earns $150 a month while the house is open for the season, receives a letter from the board secretary at one point informing her, “To us you are Miss Lunt, Custodian—I love that word because it brings in the sense of guarding faithfully!”18

1952

Trustees agree to allow Rumney caretaker Alice B. Wood to purchase a lamb. “I understand it would keep the long grass clipped and beautifully green,” Mrs. Wood writes in a letter proposing the project.19

1953

Marian H. “Heidi” Holbrook joins the Board of Trustees. She will serve for the next 51 years. On her first visit to the mansion, fellow trustee R. Howard Cooley (who himself serves nearly 30 years) “introduces” her to each of the early workers’ portraits, since none is labeled. “The next time I came I could not remember a single name,” Mrs. Holbrook later recalls with chagrin. As a result, one of her first items of business is to commission the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston to make brass nameplates for all of the portraits in Longyear’s collection—an important step as successive generations of Christian Scientists are further removed from Mrs. Eddy’s time.

1957

Guides’ salaries are raised to $1.40 an hour.

1959

Winifred and Rex Earl take over as caretakers for Rumney and North Groton. Following a storm that causes epic flooding in the area, they write a letter reporting on conditions at both houses. Using a return address of “The Ark, Rumney, N.H.,” the British couple signs it, “Best wishes from Mr. and Mrs. Noah Earl.”20

1960s

1960

Upkeep and repairs to the mansion continue to drain financial resources. A property comes on the market in downtown Boston near the Ritz-Carlton Hotel. It appears “to be an ideal plot on which to erect a new Foundation building,” the trustees report to the Board of Visitors.21 Negotiations soon are under way to sell the mansion to nearby Fisher Junior College. However, the plan has to be abandoned the following year when the City of Boston’s legal department informs Longyear that it will not be given the same tax exemption that it has enjoyed in Brookline, as the department does not consider Mary Baker Eddy “to be a person of much historical interest.”22 The trustees tell the Board of Visitors, “Inasmuch as it is probable that the foundation will continue to occupy the present building for an indefinite time, it was decided to proceed with certain necessary work… .”23

1961

The Cold War is on everyone’s radar screen, and a trustee discussion centers on “the possible need for providing shelter opportunities for employees and visitors to the Foundation, from danger of ‘fallout’ resulting from the explosion of atomic bombs.24

1961

The Wentworth house in Stoughton, Massachusetts—where Mrs. Eddy spent 18 months studying, writing, and healing following her discovery of Christian Science—is donated to Longyear, bringing the number of historic houses in the collection to five

Mid-1960s

Midway through the decade, there are five full-time and three part-time employees at the mansion, and a full complement of caretakers and guides at the historic houses.

1964

The Longyear Foundation Quarterly News debuts in the spring of 1964. With research director Anne Webb at the helm, the new flagship publication offers original research and articles about Mary Baker Eddy and the early Christian Science pioneers, helping to inspire far-flung members and friends as it shines a light on the collection and on the Foundation’s work. Receiving it, notes one member, is “like receiving a letter from home.”25

1964

The Museum hires a technical director—Jeannette Johansson, who will be succeeded by Richard Molloy. Anne Webb and administration head Charlis Vogel join the trustees on a visit to the archives of The Mother Church to discuss equipment and methods for the restoration and protection of historical data. The following year, Museum employees make a fact-finding trip to Raytheon, an early high-tech company in nearby Waltham, Massachusetts, in preparation for the monumental undertaking of cataloging the entire manuscript and document collection.

If the human life of Mary Baker Eddy is not recorded and guarded for posterity, in the years—yes, centuries—to come, legends will grow up regarding her, with no statements of Truth to refute them. I am trying to forestall all rumors and misconceptions that might arise in the future, detrimental to her character and circumstances.

Mary Beecher Longyear, June 22, 1926

1966

The centennial year of the discovery of Christian Science brings a record number of visitors to the Mary Baker Eddy Historic House in Swampscott—and to the exhibits at the Longyear mansion. Additionally, two books published by the Christian Science Publishing Society—Robert Peel’s Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Discovery and Jewel Spangler Smaus’s Mary Baker Eddy: The Golden Days, give a nod to the collection. “Both authors drew heavily on the unique collection of Baker family letters and documents owned by Longyear Foundation,” the trustees report, “and both identified meticulously each letter or document used.”26

1967

Until this point, the trustees have been working to oversee every detail of the Foundation’s operations, no matter how minute. After meeting 17 times in 1967, they vote to increase their number from three to five members, place the active management of the Foundation and the historic houses in the hands of a newly created manager position, meet just once a month (or less), and concern themselves “only with broad policy-making decisions.”27

Late 1960s

Longyear takes its first steps into development work. Several trustees hit the road with a slide presentation that tells the Longyear story. And in the early 1970s, an annual giving program will be launched, along with several other fund-raising campaigns.

Early 1970s

Belts are tightened during the worldwide energy crisis. Heating costs at the Museum rise 41 percent between 1972 and 1974. Repair bills on the mansion also continue to mount. And the collection is outgrowing its housing. “While space is critical, we can probably make do another few years,” the trustees conclude.28 More important than size considerations or cost of repairs, however, is the realization that upkeep of the mansion is diverting funds from Longyear’s primary focus—to preserve and share with the public accurate information about Mary Baker Eddy’s life and work. Clearly, something has to be done.