This October, Longyear Museum is introducing a new documentary film, The House on Broad Street, centered on the 1870s in Lynn, Massachusetts — on Mary Baker Eddy’s home there from 1875 to 1882. Her years in Lynn include events of great historical and spiritual significance. This film looks at Mrs. Eddy’s far-reaching work to establish Christian Science while living in that modest house on Broad Street. In this article Webster Lithgow, who wrote and directed the film, shares some thoughts about the challenges Mrs. Eddy met during her years in Lynn — and discusses how images were created to tell that history in the form of a documentary motion picture.

“When first Truth leads”

In Longyear’s new film, the first words that appear on the screen are Mary Baker Eddy’s:

You may know when first Truth leads by the fewness and faithfulness of its followers.1

In writing those words,Mrs. Eddy spoke from her own experience. As the standard bearer of Truth, she worked tirelessly throughout the 1870s in Lynn, Massachusetts, — writing, teaching, lecturing, preaching, and organizing an association, church, and college. For all her efforts, those dedicated to following where she led were few indeed! Yet with those few, Mary Baker Eddy accepted the mantle of Leader — and marched on toward the wider world that awaited her message beyond Lynn.

“Joys and victories”

In Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, Mrs. Eddy writes: “We must have trials and self-denials, as well as joys and victories, until all error is destroyed.”2 There were plenty of both during her Lynn years. Those years began in 1870, when Mary B. Glover (as Mary Baker Eddy was then known) began formal classes of instruction for “ladies and gentlemen who wish to learn how to heal the sick without medicine….”3 In 1872 she suspended her teaching to devote herself to writing Science and Health (initially titled The Science of Life; see illustration on page 6).

The next three years of writing while living in a succession of boarding houses, were a challenge.

A special happiness came with her settling into a home of her own in 1875. That spring,while still correcting galley proofs for her book, she was able to purchase the house at No. 8 Broad Street, the first home she had ever owned. In that house she finished writing and proofreading her manuscript. During the summer, as her book neared publication, she preached on Sundays for a congregation of her students and the public, planting the seed for what would later become a “church of my own,”4 as she put it. In the fall, stacks of Science and Health came from the bindery.Of this landmark year for Mary Glover, her student “Putney” Bancroft writes: “I never knew her so continuously happy in her work. Although she was writing, teaching and preaching, and occasionally treating some severe case beyond a student’s ability to reach, her physical and mental vigor seemed to be augmented rather than depleted.”5

Faithful few

Yet for all this happiness in her work, the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science was encountering indifference and resistance. Among her ninety-five students during these years, her hundreds of readers, the many who heard her lectures, and all those who were healed through the Science she taught, few were willing to accept her leadership and join in the great movement that was coming.

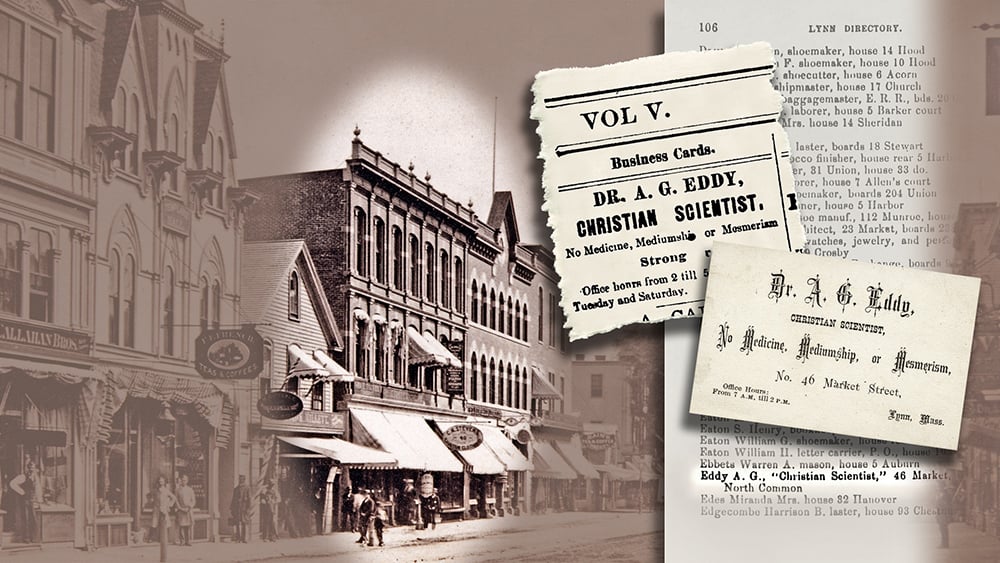

Asa Gilbert Eddy was a shining exception. In 1876, in failing health, he was urged to go to 8 Broad Street for healing. Within two visits to Mrs. Glover, he was so much better, he went back to his sales work. But a spark had been lit in him. After his class with her, he put his business career behind him and joined Mary Glover’s cause. Gilbert announced office hours in downtown Lynn (see illustration on page 7). His healing practice flourished.

During 1876, Gilbert became a steady right hand to his teacher. At year’s end, feeling he could be a helpmeet for her, he proposed marriage. After earnest prayer during the night, she accepted. The next day,NewYear’s Day 1877, in the parlor at 8 Broad Street, Unitarian minister Samuel Stewart united the couple, and Mary B. Glover became Mary Baker Eddy. Here at last was one who would follow her vision and support and defend her, as she faced the battles of that era.

“Love’s battle flag unfurled”

At the start of the Lynn years she had declared:

In the nineteenth century I affix for all time the word, Science, to Christianity; and error to personal sense, and call the world to battle on this issue.6

Her field of endeavor did indeed seem like a battlefield at times — alongside the ongoing search for true followers. By 1881, after more than a decade in Lynn, her organized followers numbered littlemore than two dozen. Then, asMrs. Eddy and her husband looked ahead to a broader field beyond Lynn, a revolt among those few left her with hardly more than a handful. But, as she left Lynn behind, she rallied that handful:

With Love’s battle flags unfurled, With hope’s Cause before the world, We are going on.7

The years ahead would be filled with “joys and victories”won by a growing legion of those willing to follow her leadership.

In 1874 and 1875 Mrs. Glover had to correct the printer’s errors without incurring the cost of re-setting entire pages of type. For months she painstakingly counted the letters of each word to be replaced, and substituted words that would both convey her meaning and fit the same spaces. Then, using tweezers, the typesetter removed erroneous words from the galleys and inserted her corrected words, one letter at a time.

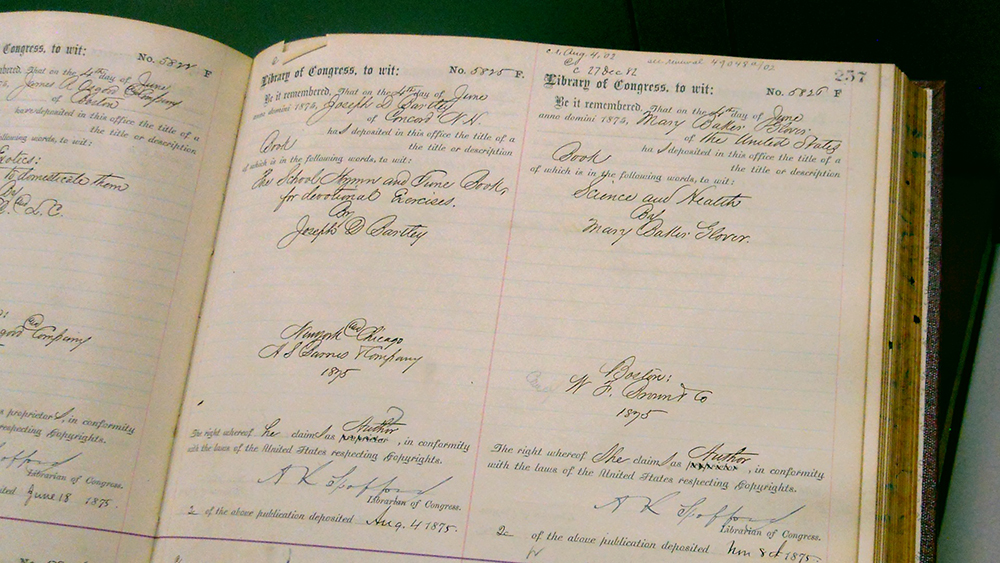

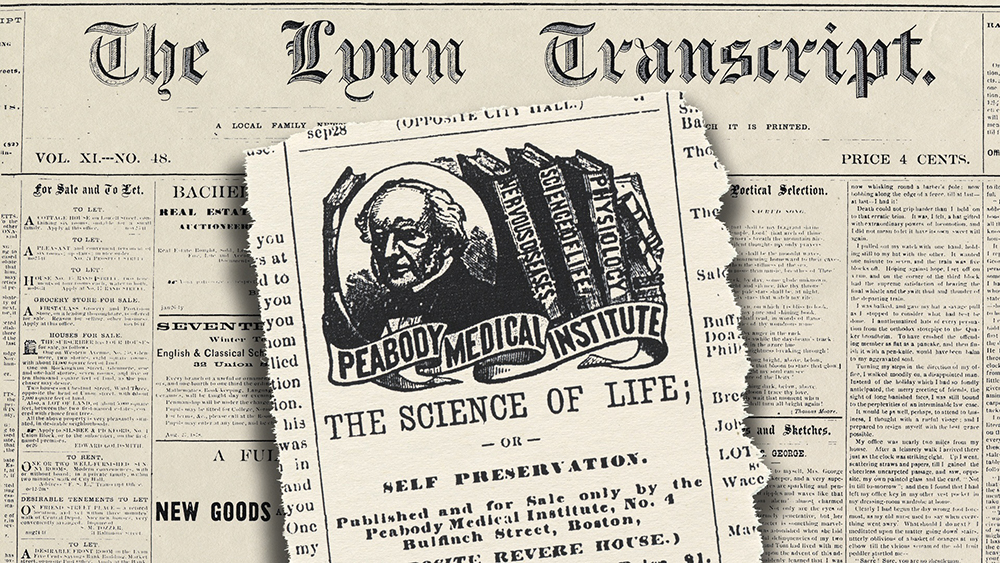

In 1874,Mrs. Glover copyrighted her book under the title The Science of Life. In 1875, in the midst of correcting her printer’s galley proofs, she realized there was a medical book with the same title. Longyear’s research uncovered ads for that book in the Lynn newspapers of the day. After weeks of prayer, a new title came to her in the middle of the night with what she said was divine authority. She promptly copyrighted that title — Science and Health — at the Library of Congress.

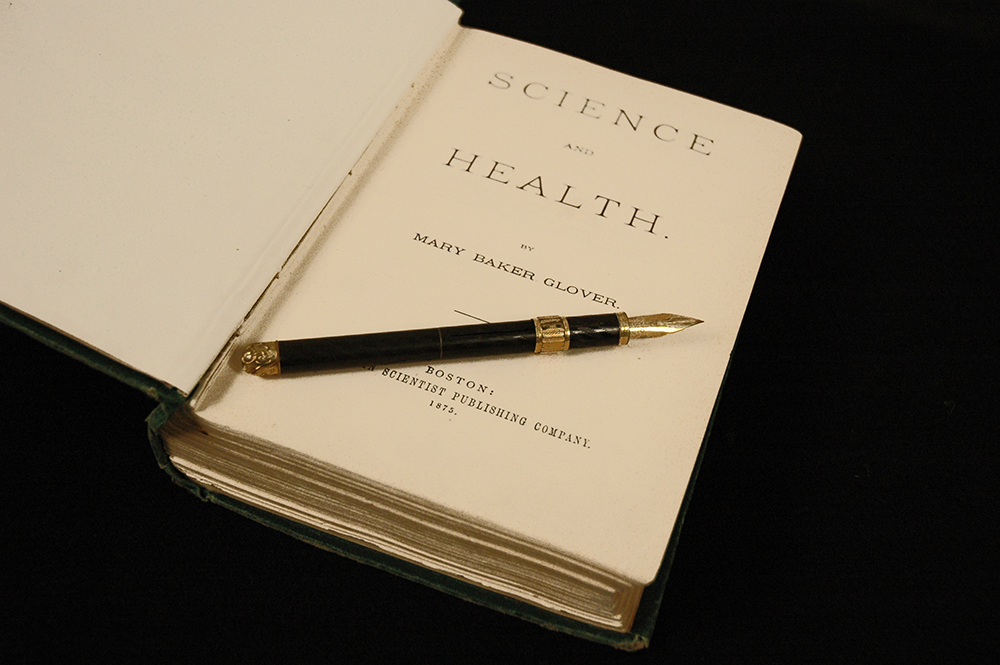

In 1875,Mrs. Glover appointed her student Daniel Spofford to be publisher of the first edition of Science and Health. She expressed her gratitude by giving him the pen with which she had written it, accompanied by a note of appreciation for his “untiring zeal in the cause of humanity, his fidelity to Truth, and efforts in behalf of Metaphysical Science.” The “zeal” was short-lived. After his promising start, Spofford resigned as publisher of her book and turned against her.

In 1876, after his class with Mary B. Glover, Asa Gilbert Eddy moved to Lynn, where he was the first of her students to announce himself to the public as a Christian Scientist, advertising: “No Medicine,Mediumship, or Mesmerism.” His office was at 46 Market Street, Lynn (highlighted) — a few doors away from the Templars Hall where the first public Christian Science services had been held the previous year.

Re-enacted scenes in the film recreate moments that could not be conveyed by historic photographs or other archival materials.Making these scenes historically authentic required a storehouse of rented garments, furnishings, décor, and functional objects that were appropriate to the period of the mid-1800s.

At Longyear Museum, the call was for “all hands on deck.”One way or another, everyone on the Museum staff pitched in. One staff member brought her nine-month-old baby to play a cameo scene illustrating Clara Choate’s account of Gilbert Eddy healing her child. Mrs. Choate recalled: “At this time my baby boy was taken violently ill.We sent for Dr. Eddy to come at once…. Upon arriving at the house, he took the baby up and laid him upon his shoulder, addressing him in a bright and cheerful tone…. In about half an hour the symptoms all changed for the better…. The next morning there was no trace of any illness…and I do not remember that the child ever had a like sickness again.”8

An evening meeting on October 26, 1881, brought the withdrawal of nearly half the members of Mary Baker Eddy’s fledgling church and association, and plunged her into a “long night of struggle”9 — and of inspiration. She valued the thoughts that came to her that night as revelations pointing the way forward for herself and her cause.

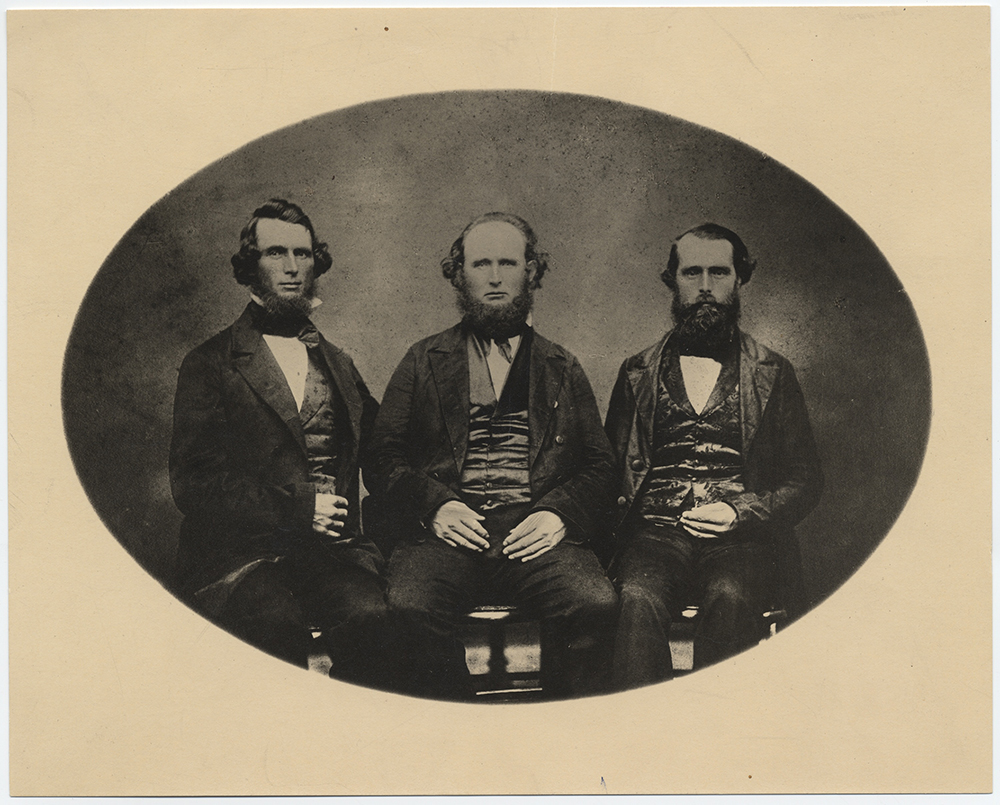

Curatorial research by alert Longyear staff settled the question as to what Mrs. Eddy’s second husband, Daniel Patterson, looked like. In this photograph of the three Patterson brothers from the Longyear collection, some interpreters have identified the darkly bearded man on the right as Daniel. The film included two visuals based on that interpretation. However, during a diligent search in the Longyear document collection, a Longyear curator discovered a letter from an eyewitness who was familiar with both the photo and the man. H.W. Herbert of Rumney Depot, New Hampshire, had written to Mary Beecher Longyear regarding the picture of the three brothers: “The middle one [is] easily recognized as the husband of the late Mary Baker Eddy, and [I] remember very well when they lived in my father’s house, and Dr. Patterson filled several teeth for me while living there.” The visuals showing Patterson were re-filmed.