When Mary Baker Eddy moved from Pleasant View, her beloved home in Concord, New Hampshire, to Boston in January of 1908, it wasn’t to pursue a quiet retirement. The Leader of the Christian Science movement had her gaze fixed firmly on the future.

When Mary Baker Eddy moved from Pleasant View, her beloved home in Concord, New Hampshire, to Boston in January of 1908, it wasn’t to pursue a quiet retirement. The Leader of the Christian Science movement had her gaze fixed firmly on the future.

“I have much work to do,” she had told a reporter from the New York American that prior summer. “I trust in God, and He will give me strength to accomplish those things which have been marked out for me to do.”1

Supporting Mrs. Eddy in her mission was a household team of metaphysical workers, secretaries, assistants, housekeepers and handymen, gardeners, cooks, and coachmen. Mrs. Eddy and her “family,” as she called her staff, had outgrown the modest Concord farmhouse, and more spacious quarters had been sought out and found for them at 400 Beacon Street in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts.2

To the world, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in the nearby Back Bay neighborhood of Boston, was the administrative headquarters of the Christian Science movement. What went on under the roof of Mary Baker Eddy’s home in the city’s leafy suburb, however — particularly upstairs in her suite of rooms — was its hub. 400 Beacon Street served as both home and executive headquarters for Mrs. Eddy and her team of workers, and it was a virtual beehive of activity.

During the time that she lived here from January 1908 to December 1910, Mrs. Eddy surmounted challenges to her leadership, continued to guide her followers through her writings, fielded inquiries from the press, approved an expanded edition of the Christian Science Hymnal, authorized the first translation of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, made final revisions to the Christian Science textbook and the Church Manual, and launched a daily newspaper — an act she would later describe to members of her household as “the greatest step forward since I gave Science and Health to the world.”3

What Mrs. Eddy achieved during these three short years in Chestnut Hill, others would have been proud to have accomplished in a lifetime.

Today, Longyear Museum is working to preserve 400 Beacon Street and restore it to the way it looked while Mary Baker Eddy was living and working here, so that it will continue to tell her story for generations to come.

“At one point, I thought that the responsibility for restoring this house might not rest with the current generation of Longyear workers,” says Sandra J. Houston, President and Executive Director of Longyear Museum. “I thought that our job was to preserve the house, and that it might be up to a future generation to actually do the restoration. But I don’t believe that any more. I think the restoration is ours to do, and that it’s ours to do now.”

In fact, work is already underway. This past fall, thanks to several generous, unexpected gifts and a matching grant from the Massachusetts Cultural Facilities Fund, Phase I of the planned restoration — a pilot project — was completed. This first phase addressed some of the most critical exterior issues, such as repointing mortar and restoring windows on the south façade and north wing, and replacing part of the roof (including above Mrs. Eddy’s study, where it had been sagging and leaking).

An opportunity and a challenge

“With its purchase of this building,4 Longyear Museum had a wonderful opportunity but also a major challenge,” explains Gary Wolf, Principal, Wolf Architects, Inc., who worked with Longyear on the restoration of 8 Broad Street in Lynn and is the preservation architect for this project. “First built in 1880, the house was more than doubled in size for Mrs. Eddy in 1907 and 1908. For over a century, The Mother Church did a wonderful job preserving this home for posterity, but anybody who owns a house knows it takes constant maintenance and upkeep. And in this case we’re talking about 20,000 square feet worth of maintenance and upkeep!”

As the initial restoration work got underway, it soon became evident that the water main, sewer line, and gas line, all of which were original to the house, needed to be replaced. The water main and sewer line were included in Phase I; the gas line will be a separate project this summer.

Another aspect of Phase I dealt with meeting current building code requirements, such as asbestos and other hazardous materials abatement and compliance with accessibility laws.

“In a building that the public comes to visit, we need to eliminate barriers to access,” notes Mr. Wolf.

In order to do so, the driveway’s grade was raised to bypass a step outside the front door, a handicap-accessible parking spot was added, and the existing first-floor powder room was completely remodeled into an accessible restroom. Ultimately, when the house is fully restored it will also need to have a working elevator, in order to ensure that visitors unable to climb stairs can access all four floors.

Phase I wasn’t only about the building’s structural and mechanical features, however.

A house with a story to tell

“There’s more to this house than just taking care of the systems and the exterior envelope,” says Wolf. “There’s a story here. That’s why Longyear bought the building, to tell the story of what went on in this house.”

In order to help facilitate this, three significant areas were selected as the interpretive focus for Phase 1.

At the center of the story that the house has to tell are the suite of rooms in which Mrs. Eddy lived — her study in particular. It was here that she did most of her work, here that she frequently gathered her household for ongoing instruction and counsel, here that she met with visiting members of the Christian Science Board of Directors and others.

Needed repair work addressed everything from water-damaged plaster to worn carpeting. Missing doors were rehung, walls and trim freshly painted, gas lamps over Mrs. Eddy’s desk and on the walls restored, while framed reproduction artwork and furniture of the period replicate how the room would have looked to Mrs. Eddy as she went about fulfilling her God-appointed mission.

The next area identified as one that could have an impact on the interpretive aspects of the house was the kitchen. A reporter from the Boston Post who toured the house in 1909 was clearly impressed by it: “The kitchen is a very large room, 20 feet or more in length, and fitted with all the conveniences and improvements of the most up-to-date hotel’s culinary department.”5

The “conveniences” and “improvements” he referred to included spacious pantries, an oversized double sink, two stoves, and an icebox, along with all the culinary equipment needed to feed a staff of up to 20 or so, along with frequent visitors.

In recent years, however, the kitchen wasn’t part of the house tour. “Visitors weren’t taken there,” explains Pam Partridge, Visitor Experience and Historic House Team Leader. “It had been drastically changed after Mrs. Eddy’s passing.”

Although the floor plan hadn’t been altered, at some point everything in the room had been painted white — walls, trim, doors — and carpeting and a metal ceiling added. The first order of business was peeling back these layers to reveal the finishes true to Mrs. Eddy’s day. Paint analysis helped determine the colors on the walls and trim. Scraps of the original linoleum, buried beneath added flooring, were brought to light and matched to modern-day materials. Gas light fixtures (now electrified) were restored. Research into primary source material — letters, photographs, newspaper accounts, reminiscences, household records, store receipts, and the like — uncovered clues from eyewitnesses as to how the kitchen would have looked in 1908. All of these avenues aided in recreating the original room, which was an important part of life at the house.

The kitchen’s crowning jewels are a pair of ornate cast-iron stoves. When the restoration began, both were missing. The smaller one, a Vulcan gas range manufactured by William M. Crane Company of New York, was found languishing in the basement. It was restored and returned to the spot where historic photographs show that it had stood. The other, a massive wood or coal-fired Kitchener double oven made by Magee Furnace Company of Boston, had long since disappeared, but after an extensive search the team was able to track down and purchase a nearly-identical one.

An unusual feature of the room that was quite common in Mrs. Eddy’s day is the faux finish on the woodwork that makes everything look like oak. “Labor was so inexpensive at that time that the architects would specify a general white wood, which could then be finished to look like any kind of wood you wanted,” Gary Wolf explains. During the restoration, this faux finish was reproduced by expert craftsmen.

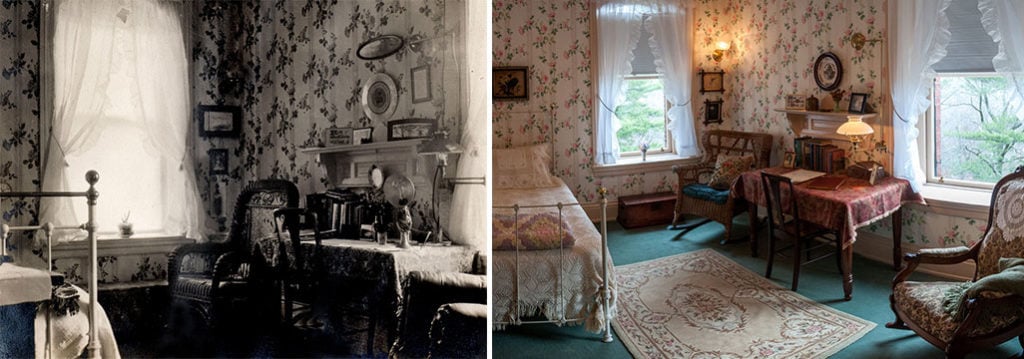

The third and final room to undergo restoration is one of the smallest in the house. It belonged to Katharine Retterer, a housekeeper. In any other household of the era, Miss Retterer would most likely have been considered merely a domestic servant. In Mrs. Eddy’s household, she was family. As such, her cozy, well appointed room stands in sharp contrast to the utilitarian servants’ quarters a visitor might see while touring other historic estates of the same period. At 400 Beacon Street, metaphysical workers and groundskeepers, secretaries, housekeepers, maids, and cooks alike — all were given every consideration by Mrs. Eddy for their comfort.6 Restoring Miss Retterer’s room helps underscore this fact for visitors.

Altogether, this trio of rooms help tell the story of how Mrs. Eddy’s household worked under her leadership to support her labors for the Cause of Christian Science — labors which were wide-reaching. As she told the reporter from the New York American just a few months prior to her move to Boston, “I can still do a vast amount of work. All my efforts, all my prayers and tears are for humanity, and the spread of peace and love among mankind.”7

While full restoration of the house is the ultimate goal, Longyear’s plan is to move forward, guided by “wisdom, economy, and brotherly love,”8 as funds become available.

Above, left: Carpenters install newly-restored windows in the kitchen. Right: Historically-accurate paint and faux grain on the finished woodwork glow in the late afternoon light.

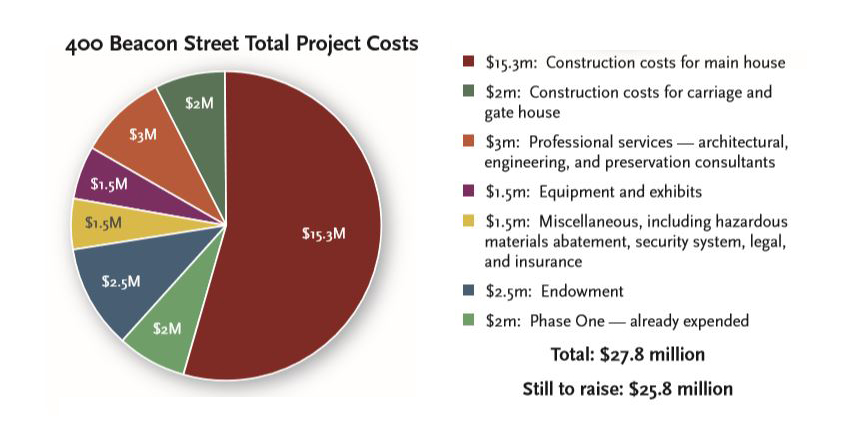

This will be the Museum’s largest project to date, with a total price tag of $27.8 million. Phase II will complete the repair work on the building’s exterior envelope, and include new electrical, HVAC, and fire suppression systems, as well as additional accessibility requirements. Some interior restoration of period rooms is also slated, for a total cost of $13.5 million. More details will be forthcoming on fundraising for Phase II in the coming months.