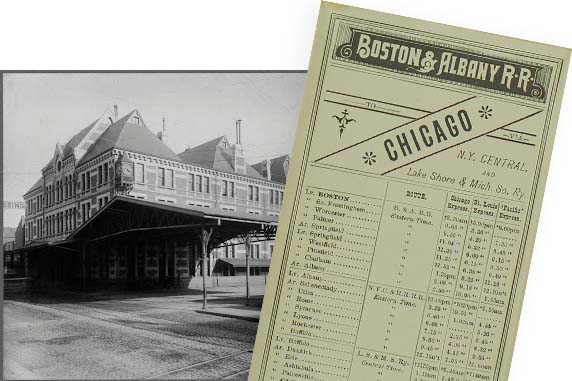

On Tuesday morning, May 6, 1884, at the Boston & Albany railroad terminal on Kneeland Street in Boston’s South End, an inconspicuous party of three boarded the 8:30 Chicago Express. The traveling party included Calvin Frye, secretary, and Sarah Crosse, assistant, from the Massachusetts Metaphysical College. With them was their teacher and president of the College, the Discoverer, Founder, and Leader of Christian Science. Mary Baker Eddy was heading west. She was bringing with her the correct teaching of Christian Science healing—and a vision of spreading that Science to bless all mankind.

A visitor from Chicago

Mrs. Eddy’s thousand-mile western journey sprang from a visit to Boston two years earlier by one lone, alert businessman from Chicago by the name of Bradford Sherman. In 1882, while in Boston, Mr. Sherman came upon the case of a man whose doctors had told him he was so far gone that he could not live more than a couple of days. With that prognosis staring him in the face, the man desperately turned to a Christian Science healer—called in a so-called “crank.” his friends scoffed. Remarkably, the prayerful treatment by the “crank” restored the man’s health.1

Like so many in the American West, Sherman was wide open to new thinking. Impressed by that one healing of a “hopeless” case, he obtained the latest edition of the Christian Science textbook,Science and Health2 by Mary Baker Eddy, and read it through. He brought copies with him on his return trip home.

In Chicago—with no teacher but that textbook —Bradford Sherman, his wife, Mattie, and their son, Roger, began to practice and teach Christian Science healing as best they could. As Mr. Sherman later recalled: “Chronic cases were healed and various forms of suffering were relieved. The demands upon our time for help were more than we could attend to.”3

Learners and doers

Simultaneously, back in Boston, Caroline Noyes, a family friend of the Shermans, had also been impressed by a case of Christian Science healing—perhaps the same case that caught Sherman’s attention. Curiosity led her to attend one of Mary Baker Eddy’s public lectures. Through the winter of 1882-83, Caroline studied a copy of Science and Health in tandem with the Bible. Like the Shermans, she immediately put into practice what she was learning. Several cases were healed. Traveling up to Maine, she dropped all other cares to devote herself to this healing work.

On her return to Boston that spring, she healed several more cases, and she continued attending Mrs. Eddy’s public lectures in Hawthorne Hall. Years later she vividly recalled Mrs. Eddy at the podium: “Her grace, dignity, and freedom of expression were very remarkable…. The fine expressive dark eyes. . . beamed with kindness and intelligence.”4

It was at this point that Caroline received a letter from the Shermans. Overwhelmed by the flood of sufferers and inquirers, they urged her to come to Chicago and join them in the work there. She promptly packed up and headed west. Within a matter of weeks, she herself was so busy that she wrote her friend Ellen Brown, who had been assisting Mrs. Eddy’s household in Boston, asking if she would come to Chicago, too. In short order, the two women were setting up shop in rooms on Washington Boulevard. A sign in their window read: “Mental Healing.”

None of these people in the West, however, not even Ellen Brown, had actually studied with Mary Baker Eddy. As a result, they were somewhat swept up in the widespread confusion in Chicago over what constituted Christian Science healing. That confusion would be rectified by steps taken by a couple in neighboring Wisconsin.

Mrs. Eddy’s first students from the West

Among the Shermans’ patients was a woman named Fannie Silsbee from Columbus, Wisconsin, who was suffering with a tumor. She came to Chicago to see the Shermans and was healed. Grateful to be free of the condition, Fannie wanted to know how to practice this method of Christian healing herself. Bradford Sherman provided instruction, drawing from his understanding of the Christian Science textbook. Fannie then moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and launched into her own healing practice.5

News of healings like hers reached Silas Sawyer, a successful Milwaukee dentist who was looking for some way to relieve or cure his desperately ill wife. For fifteen years, Jennie Sawyer had been an invalid, largely house-bound and suffering constant pain even from the touch of her own clothing. Medical treatment had failed to help. Deeply religious, she sought comfort in her Bible. But the comfort was scant. “My constant prayer,” she recalled later, “was that I might die… [and] enter eternal rest.”6

Seven weeks into a rest-cure at a sanatorium, Jennie received an astonishing letter from her husband. Silas had been reading Science and Health. He didn’t understand much of it, but he urged that they go to Boston and consult the book’s author, Mary Baker Eddy. Jennie, at that stage of her life, was too weak to turn a book’s pages. The idea of a thousand-mile trip to Boston filled her with dread. But Silas had become impressed with this practical, demonstrable form of Christian faith. After two months of persuasion and preparation, the Sawyers arrived in Boston in December 1883 for an appointment at the Massachusetts Metaphysical College, which was also Mrs. Eddy’s home. 7

In her first meeting with Mary Baker Eddy, Jennie was too weary with pain to take in fully what Mrs. Eddy was explaining. But she was touched by Mrs. Eddy’s “womanly, motherly kindness,” and her hopes were raised by “the idea of gaining health through abiding in God’s omnipotence.” Jennie was looking for Mrs. Eddy herself to take her case, but Mrs. Eddy had other ideas: “I would advise you to sit in my class and let me teach you.” 8

Jennie was stunned. Doctors had warned she might die at any moment. She was too weary to think, let alone study. Merely having people around her, talking, exhausted her. Sit in a classroom for two whole weeks? Impossible! But Mrs. Eddy assured her, “You will be able to sit in this class.” 9

The following Monday, that is exactly where Jennie was.

Mary Baker Eddy as teacher

In the classroom, Jennie found her teacher to be “prepossessing, attractive, and kind . . . guiding the thought of the members of this class away from discussions in relation to matter as the only tangible evidence of life.” She recalled that whenever one of the students caught her spiritual meaning, their teacher’s face would “become actually radiant with the spiritual uplift.” 10

Jennie was unaccustomed to any physical or mental activity, least of all the rigors of intensive study. The twelve-lesson course was often a struggle. Her despair over failing to rise to the mental and spiritual heights required in the classroom brought her to tears. Mrs. Eddy reassured her that she was “in the most favorable condition of mind of anyone in the class.”11 She invited the Sawyers to a private talk in the evening and gave Jennie special encouragement. She let them know she valued them as her first students from the West. Partway through the course, Mrs. Eddy called a recess to let Jennie have a few days of respite, extending the course to three weeks. The lessons resumed, and Jennie rose to the challenge. At the conclusion, she was well.

As the Sawyers departed, Mrs. Eddy asked Jennie what she was going to do with what she had taught her. Apparently Jennie hadn’t thought about that. “I don’t know what I’m going to do with it!” she said. Her teacher replied, “You are going to heal with it!” 12

And she did.

Jennie’s first case

Back home in Milwaukee, late on a Friday, Mrs. Sawyer’s very first case came to her door. The patient was a young woman with inflammatory rheumatism affecting her right arm, which hung limp and useless in a sling. She could not even open her right hand. Jennie began treatment at once. Monday morning the girl called on her again to announce, “See what I can do!” She reached out to the table, grabbed a heavy atlas, and lifted it in the air—with her right hand.

The young woman also had been born with a spinal double curvature, and had lived with that deformity all her twenty years. She asked Jennie to treat the problem. A week later the girl’s back was so straightened she could wear a normal straight-cut corset for the first time—as Jennie joyfully reported back to Mrs. Eddy. 13

So began the Sawyers’ Christian Science practice in Milwaukee, treating anyone who asked for help—at first, for no charge, despite Mrs. Eddy’s instruction that Christian Science practitioners charge a fee commensurate with the fees of medical practitioners. Many of the Sawyers’ cases were considered chronic and incurable. With each person healed, word spread. More patients came. Silas closed his lucrative dental practice to concentrate on his new metaphysical practice.

As for his wife, whom doctors had given up as incurable? Jennie Sawyer would still be actively practicing and teaching Christian Science healing nearly 50 years later.

A Chicago “craze”

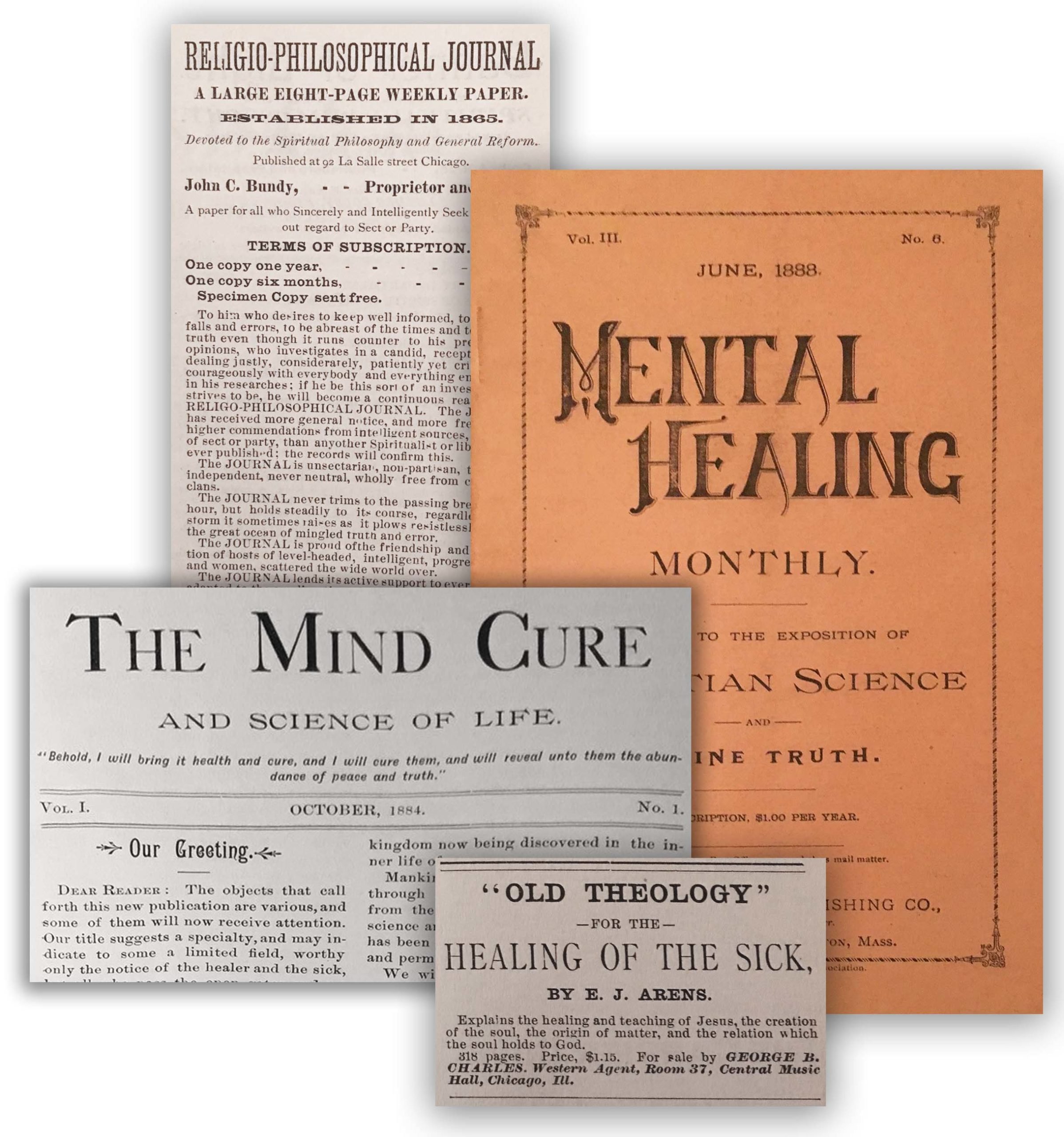

During this same year, 1883, as reports of Christian Science healings grew, so did opposition to the religion. Some Bostonians derisively mocked Mrs. Eddy’s discovery as the “Boston craze.” What was going on in Chicago in the early 1880s might better have deserved that term. There, opposition often took the form of imitation. Spurious imitators of Christian Science were spreading like a second Chicago firestorm. In a broadside, one such imitator promoted his system as embracing “Mediumship, Clairvoyance, or Magnetism.”14 Announcements presenting what claimed to be “Spiritual Healing” fed public curiosity. Mental-cure magazines, in many cases plagiarized from Mrs. Eddy’s writings and lectures, were widely published.

Under this influence, Fannie Silsbee was combining what she had learned from Bradford Sherman and from reading Science and Health with the practice of sitting in back-to-back contact with a patient during treatment.15 Others offered even more bizarre methods in the name of what they called “Christian Science.”16 Even the Shermans and Caroline Noyes were evolving their own variant concepts.

“The West needs your labors”

In January 1884, the Sawyers returned from studying with Mrs. Eddy in Boston, Jennie having been healed there. They and Ellen Brown, who had attended the same class, met with the Shermans’ circle to share what they had learned. It began to dawn on those who had not yet studied with Mrs. Eddy that they had gotten off-course from the one universally correct way to understand and practice Christian Science healing. Bradford Sherman remarked to Fannie Silsbee: “Well, we have had our foundation knocked out from under us….” 17

The very next month, February 1884, Bradford and Mattie Sherman, their son, Roger, Fannie Silsbee, and Caroline Noyes were all in Boston, enrolled in Mrs. Eddy’s Primary Class at the Massachusetts Metaphysical College. On their return to Chicago some weeks later, patients were waiting to be healed; word was continuing to spread; and some were asking for further instruction and enlightenment. All this was unfolding very rapidly.

The Chicago workers saw that if Christian Science was to continue broadening its horizon, correct teaching was imperative. By April, the Shermans and the Sawyers were appealing to the College to send them a qualified teacher. Roger Sherman wrote Mrs. Eddy: “I think the West needs your labors.”18 With no one else prepared to go, Mrs. Eddy saw that it was she herself who must answer the call. As she put it:

“I went in May to Chicago at the imperative call of people there and my own sense of the need. This great work had been started, but my students needed me to give it a right foundation and impulse in that city of ceaseless enterprise.” 19

Thus it was in May of 1884 that the train carrying Mary Baker Eddy was steaming down from New England’s western hills, past the orchards, farms, and foundries of New York and Pennsylvania, through the night across Ohio and Indiana, and at dawn around the curve of Lake Michigan toward the boomtown of Chicago, fully rebuilt after its great fire a decade earlier.

Her journey marked a pivotal moment in the history of the Christian Science movement.

Mrs. Eddy’s Chicago class

The Shermans, Caroline Noyes, Ellen Brown, and the Sawyers had arranged a class of twenty-four, larger than any of Mrs. Eddy’s classes to date. Most of the students came from Chicago, with a handful from Wisconsin, including a woman from Oconto named Laura Sargent, who had recently been healed and who would go on to a lifetime of service for Mrs. Eddy.

The classroom, filled with rented folding chairs, had been set up in a spacious home at 470 Randolph Street.20 At the front, seated beside a small table holding a Bible and Science and Health, Mrs. Eddy greeted members of the class, asking each one to occupy the same seat every session. Students took their places, facing her steady, searching gaze that, at times, seemed to look far beyond them. Mrs. Eddy spoke gently, gracefully, but her voice was firm in correcting faults. One student recalled her “affectionate and endearing manner” that could also be “tactful, convincing, and forceful.”21 Another student wrote: “The truth drawn from her lessons—and association with her—changed the whole character of one’s future years, and her own wonderful spirituality seemed to be imparted to her faithful students.” 22

“Whom do men say that I am?”

Following the two weeks of classes, Mrs. Eddy felt there was a need for her to voice a particular message to the public at large. A lecture was announced for her last Sunday in Chicago. The hastily chosen venue was at the Hershey School of Music. As a couple of hundred attendees filed into the bare recital hall, Mrs. Eddy was seated before them on a plain wooden platform. Beside her on a table was a bowl of yellow flowers, the only decorative note in the dusky auditorium. Rising to face her small audience, Mrs. Eddy addressed the great issue underlying the confusion and fragmentation in Chicago. 23

She took as her text the question Jesus posed to his disciples: “Whom do men say that I am?” In Science and Health she paraphrases that question: “Who or what is it that is thus identified with casting out evils and healing the sick?”24 No word-for-word record of her address has been found, but the choice of text suggests its message: A recognition of her as the sole Discoverer, Founder, and Leader of Christian Science was crucial to a correct understanding of Christian Science itself. 25

With her theme set by that Biblical citation, she launched into a 45-minute talk on Christian Science healing—as she alone taught it. Those who were there recall her voice ringing out clearly, every statement landing with great conviction. 26

Two days later, her mission to Chicago complete, Mrs. Eddy and her assistants were on the train back to Boston.

A class for teachers

While healing would continue to plant seeds for the spread of Christian Science, after Chicago it was clear that correct teaching would be needed to grow those seeds into fields ripe for harvest. Her book could not do it alone—nor could she. There would have to be teachers, teaching Christian Science precisely as it was being taught by its Discoverer and Founder.

Just three months after Mrs. Eddy’s return to Boston, in August 1884, the Normal class was born. The preparation of teachers of Christian Science had begun. Mrs. Eddy’s first Normal class at the College included such Boston students as Julia Bartlett and Calvin Frye. Her second Normal class in February 1885 would reach farther afield. Five from Chicago would be there, all three Shermans along with Ellen Brown and Caroline Noyes. 27

The following year, 1886, the Sawyers would attend the Normal class. By that time, Caroline Noyes would have taught young Sue Ella Bradshaw, who would in turn bring Christian Science to San Francisco. Bradford Sherman would have traveled to Colorado to teach classes in Denver. Over the next few years, at Mrs. Eddy’s direction, Silas Sawyer would be teaching and helping hundreds of Scientists in several cities organize themselves into associations and churches.

Just three years later, in 1889, at the close of the Massachusetts Metaphysical College, there would be nearly 250 teachers prepared by Mary Baker Eddy to teach Christian Science healing as she herself taught and practiced it. With this growing cadre of teachers, the message of Christian Science was already spreading across America’s still-pioneering West.

Coming in the spring issue: A WESTWARD WIND, Part 2: Colorado

Web Lithgow, Multimedia Producer for Longyear Museum, has written and directed six Longyear documentary films: The Onward and Upward Chain (2004), Remember the Days of Old (2005), and Who Shall Be Called? (2008), The House on Broad Street (2012), Upon Life’s Shore (2013), and “Follow and Rejoice”—Mary Baker Eddy: The Chestnut Hill Years (2015), and has written articles for Longyear publications and website.

This article was first published in the Fall / Winter 2017 Longyear Museum Report To Members Newsletter.