“In 1884, I taught a class in Christian Science and formed a Christian Scientist Association in Chicago. From this small sowing of the seed of Truth, which, when sown, seemed the least among seeds, sprang immortal fruits through God’s blessing and the faithful labor of loyal students,—the healing of the sick, the reforming of the sinner…”1

—Mary Baker Eddy

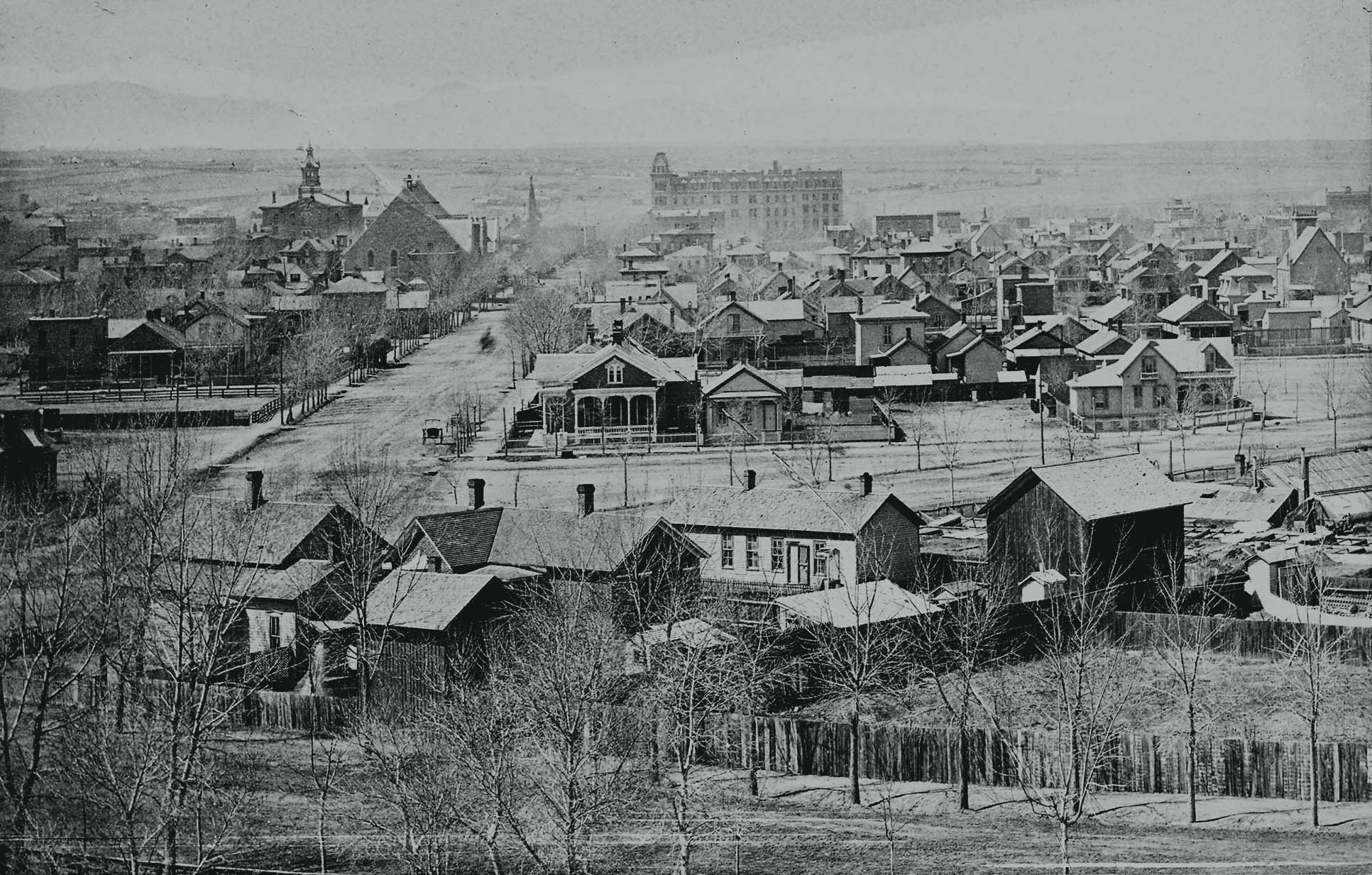

In the 1800s in the United States, a westward wind stirred the air. As settlers spread out from eastern states across the plains of the Midwest toward the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific coast, an expansive, open-minded spirit was sweeping the still-young nation. People were eager to leave the old and move forward to new spaces, new ideas—no matter what adventures might lie ahead.

That vigorous pioneering spirit was evident in Mary Baker Eddy’s thousand-mile western journey in 1884 from Boston to Chicago. There, she taught one class of 24 students and delivered a public address to a small audience.2 It might seem that such a modest venture could make little difference. But that historic missionary journey planted the correct teaching of Christian Science healing. How that seed took root and grew is evident in the stories of two frontier women in Colorado—stories that would be echoed in thousands of lives across the American West.

Pioneer spirit in the Rockies

A forward-looking frontier spirit certainly characterized Mary Melissa Hall of Denver. At age 16, back in her home state of Michigan, she married a man named Nathan Nye. Looking to strike it rich in the Colorado gold fields, Mr. Nye brought his wife and their two children by ox-drawn wagon to the Pikes Peak area. Alas, Nye turned out to be an abusive alcoholic who eventually took the children with him and abandoned Mary Melissa in a mining camp.3 In short order, an ad hoc miners’ court was convened and granted her an uncontested divorce.4

In the winter of 1861, the young woman found herself living on her own among prospectors encamped in a Colorado mountain valley. One day, far off in the snow-covered hills, there were gunshots—a signal for help. The miners formed a rescue party and found two prospectors who had been lost for weeks. Hardly able to crawl, the men had survived starvation by boiling their boot tops and leather breeches for food. The one who had fired the gun weighed only 48 pounds. His name was Charles Hall. Mary Melissa nursed him back to health. Mr. Hall continued prospecting for gold, but he would find his fortune with a salt spring, as salt was of great value for metallurgy and other purposes. Hall went on to establish a salt refinery, mines for other minerals, and a cattle ranch in the hills. And he married his nurse.

As Hall’s wife, Mary Melissa spent the next years mainly at his Salt Works Ranch. The remote location demanded self-reliance, independence, and courage. At one point, there was a battle on the Hall property between Cheyenne and Arapahoe tribes and their enemies, the Ute nation. The Utes were on friendly terms with the settlers, and sometimes came to the door for food. The ever-caring Mrs. Hall even nursed wounded Ute fighters in her home.

There were also outlaws to contend with. One of them burst into the Halls’ home one day when Mary Melissa was alone, and threatened to kidnap her. She coolly raised a loaded rifle and ordered him to put up his hands. The man quickly obeyed—fortunately for him because, as one historical account records, “Mrs. Hall was a dead shot!”5

This combination of motherly kindness and fortitude defines the spirit of a woman who would pioneer Christian Science in Colorado. Her children, too, would demonstrate that same spirit.

Turning a sudden corner

Charlie Hall’s mining ventures prospered. As the wilds of Colorado Territory were tamed into the 38th state,6 he became a business and government leader. In addition to the ranch, the Halls also occupied one of the larger homes in Denver, where their daughter Minnie was born in 1863. A son, Charles, arrived in 1865, followed by another daughter, Nettie, in 1869. In their younger years, the Hall children spent most of their time at Salt Works Ranch in the hills, where they often rode four miles to school on horseback.7

Later, the family lived full time in Denver so the children could attend local academies. Minnie’s life-goal, at age 22, was to pursue art as a career. She showed great promise, having studied painting and sculpture in Chicago and New York, and she had learned French and German in preparation for studying in Europe.8

But then debilitating physical troubles overtook her mother—and, suddenly, all of their lives turned a corner. In early 1884, Mrs. Hall lost her sight. She was told the condition was irreversible. Then, she injured her foot severely. For a year and a half, she could neither see nor walk. Doctors in Denver diagnosed the foot injury as life threatening. They foresaw the possible necessity of amputation.

This plucky frontier women would have none of that. In June of 1885, she and her daughters boarded a New York-bound train, hoping to find more advanced treatment in the East. They did find it—but not at all the way they expected.

“The blind see, the lame walk”

En route, the Halls stopped off for a brief stay in Chicago. While there, they met a friend whom doctors had diagnosed with cancer. Now, she was recovered—due entirely, she told them, to Christian Science. Mrs. Hall had resigned herself to blindness, but this new approach to healing impressed her. Accustomed to heading in new directions, she decided to stay in Chicago and try this Christian Science treatment for her injured foot. She and her daughters contacted Roger Sherman, who was fresh from Mary Baker Eddy’s Primary class in Chicago, and her Normal class in Boston. It took two men to carry Mrs. Hall up the steps to Mr. Sherman’s office. While treatment progressed, Minnie and Nettie threw themselves into studying Mrs. Eddy’s book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, reading it aloud to their mother day and night. Minnie reports: “At the end of three months, we were rewarded by ‘the light coming into the eyes,’ as she expressed it.”9 Soon, their mother was walking. And she could see! Guests at their boarding house were amazed—so much so, that some of them took up the study of Christian Science themselves.

Like his son Roger, Bradford Sherman had just completed the Normal class with Mrs. Eddy. One of the first classes he taught on his return to Chicago included Mrs. Hall and her daughters. Minnie describes what occurred during this experience and the months preceding it as “the unfolding of a Christian life from the old school to the new, from being unable to pray with understanding, to that understanding gained by Divine Science.”10

In September, after their class with Bradford Sherman, the Halls packed up and headed home. What happened next embodied the exuberance with which Christian Science flourished in America’s West.

Patients on packing crates

The Hall family was well known in Denver, as were Mrs. Hall’s afflictions. When she returned home healed, word traveled fast. The news was also spread by an unlikely courier—a somewhat ragged, white-haired scissors-grinder. He was a familiar character around town, easily spotted by his scraggly white beard—and his crutches. Years earlier, he had lost the use of his legs, and now, swinging between his crutches, he hobbled from door to door plying his trade. One day, he came to the Halls’ to sharpen some knives. As he worked, Minnie told him how her mother’s foot and eyesight had been healed and tried to convey what she had learned about Christian Science. She must have shared this with great conviction, because the man insisted that Minnie herself come to his home the very next day to heal his crippled legs. Minnie agreed.

Her mother would not have her 22-year-old daughter going off to visit a man alone, and so she went along with her. They found his cabin and knocked on the door. The tiny home’s one small sitting room was furnished only with a bed and some grocer’s packing crates. Seated on the crates were the man’s ailing neighbors, waiting expectantly. The scissors-grinder had invited them to come and be cured. Just like that, Minnie and her mother were plunged into the practice of Christian Science healing!

The small house offered no place for privacy, so the novice practitioners improvised. They went around the circle from person to person, sharing statements of truth as best they could. Each patient who came that day was soon healed. One of them, a consumptive who had not been expected to live more than a day or two, was restored to health and went to work as an express man at the Denver train depot.

For his own part, the scissors-grinder improved rapidly. One day while treating him, Minnie simply told him to walk, if that was what he wanted. He rose and took a few steps. His astonished 16-year-old child had never seen him walk before. Within three weeks, the man threw away his crutches. After that, he found he had no time for work. “All I can do,” he said, “is tell people how I was healed. They stop me at every corner!”11

Thanks to that one woman, Mary Melissa Hall, her two young daughters, and a poor scissors-grinder, word of Christian Science spread through the city. Before long, people were coming to the Halls’ home for healing at a rate of up to a hundred visitors a day.

Correct Christian Science teaching comes to Denver

Mrs. Hall quickly saw that more Christian Science healers were needed. And this growth called for the same correct teaching she had received from Bradford Sherman—which he had received directly from Mary Baker Eddy. Mrs. Hall wrote to Mr. Sherman urging him to come to Denver to teach a class in Christian Science healing. She had barely ten students lined up, but she promised him there would be more. So certain was she, that she deposited a thousand-dollar advance in the bank to guarantee that enrollments would cover expenses.12 Her husband warned that she was going to lose the money, because there would never be that many people willing to take up the study.

Charlie Hall hadn’t reckoned with the number of people who were being healed by his wife and daughters. By the time Sherman arrived in December, nearly 100 prospective pupils had signed up! They had to be divided into classes, which Sherman taught day and night. Then he returned to Chicago.

Just weeks later, the Halls gathered another batch of students. This time there were about 45. In February 1886, Sherman was again on the west-bound train to teach in the Rockies. Thus it was that, little more than a year after Mary Baker Eddy’s westward-looking mission to Chicago, Colorado was home to nearly 150 class-taught Christian Scientists.