It is a hymn of liberty, of gratitude, of prayer;

Ten thousand throats are sending forth across the valleys fair;

A hymn whose echoes shall increase, to gladden the forlorn,

And guide men’s feet to paths of peace, through centuries unborn!

Near where the fair White Mountains uplift their stately rim,

The pilgrim host is gathered and Truth’s ensign is unfurled:

And, lo, ten thousand voices join in the joyous hymn

That floats around the world!

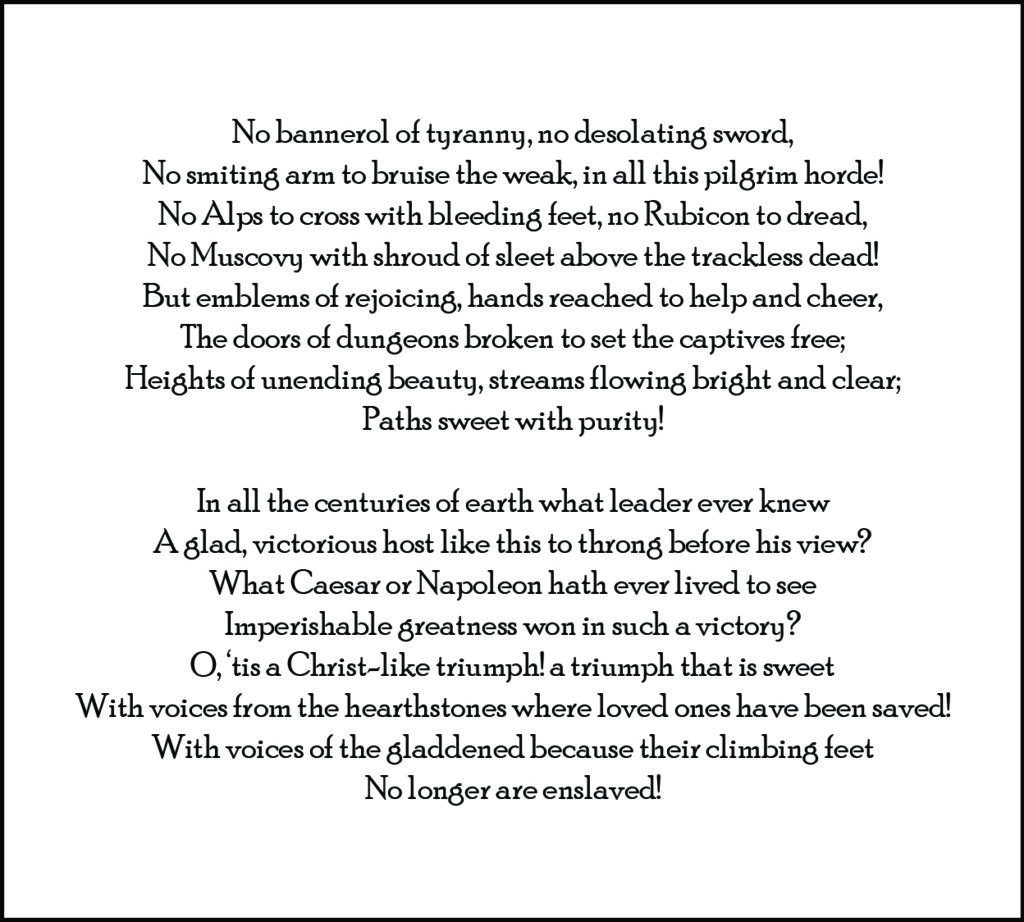

One of those ten thousand voices echoing across the “valley fair” that memorable Monday afternoon belonged to Clarence Buskirk, whose poem commemorating the event, “At Pleasant View June 29, 1903,” would be published in a New Hampshire newspaper a few months later.1

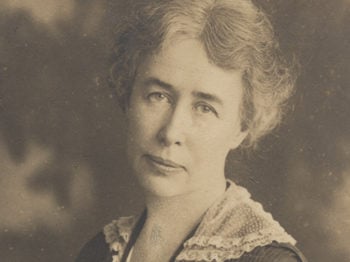

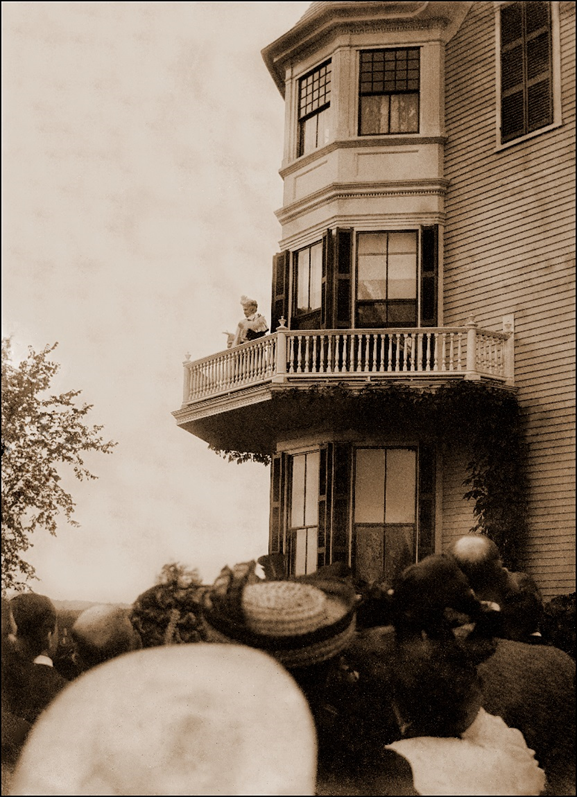

Following the annual Communion service of The Mother Church the previous day, Mary Baker Eddy had surprised the congregation with an invitation to her home in Concord, New Hampshire.

“A moment only must it be,” she had cautioned, “for my moments are precious and belong to God.”2

Like most of the others in attendance at the service, Mr. Buskirk had jumped at the opportunity to see Mrs. Eddy even for “a moment only.” Taking a train north from Boston to Concord, he joined the “greatest throng of guests within the city gates which has ever been known in a single day.”3 As was the case with so many in the crowd, the path that brought him to Pleasant View, and to Christian Science itself, began with a healing.

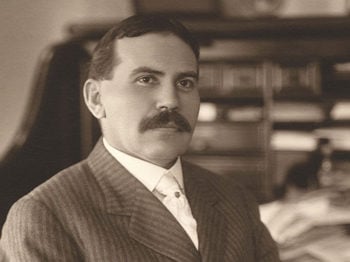

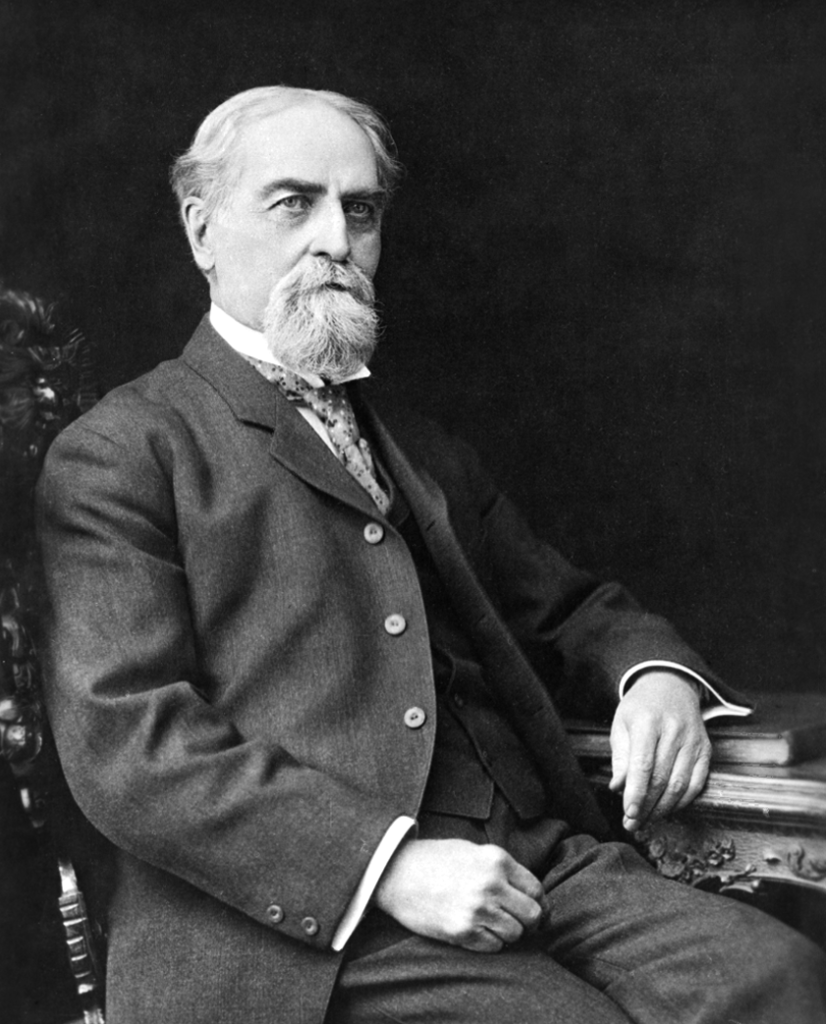

A man of the law

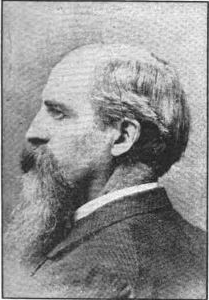

Clarence Augustus Buskirk was born in Friendship, New York, on November 8, 1842, to tailor and merchant Andrew C. Buskirk and Diantha E. Scott. The youngest of four boys,4 he attended public school and Friendship Academy, then taught locally for a time until he had saved 45 dollars—enough to purchase a ticket to Kalamazoo, Michigan, where an older brother lived. There, Clarence farmed in the summer and taught in the winter, and when he was 18 years old he ventured out on his first business enterprise: harvesting and selling potatoes.5

In 1861, he used the proceeds to launch his next enterprise—the study of law—and the following year he entered law school at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.6 Admitted to the bar in 1865, Clarence quickly made his mark as an attorney.7

“Mr. Buskirk ranks among the ablest in the state, and as a pleader and advocate has few equals,” wrote one of his contemporaries. “His great forte in the management of cases is the complete mastery of all details, and he is remarkably skillful in his manner of handling and bringing out evidence. In the presentation of cases before courts and juries he is clear, concise and logical in his statements, and his speeches are generally very ornate and eloquent.”8

Mr. Buskirk moved to Princeton, Indiana, in June 1867, where he would practice law for the next 38 years. Meanwhile, that November he married Amelia Fisher. The Buskirks would eventually have three daughters—Ella, Zelia, and Agnes.9

Several years later, Clarence was elected Gibson County representative in the Indiana state legislature, and he also served two terms as Attorney General of Indiana.10

“She came home to us a new creature”

In 1895, Clarence’s life took an unexpected turn.

For many years his oldest daughter had been an invalid, requiring constant care and attention. Clarence and his wife took Ella to sanitariums and mineral springs in the United States and Europe, as well as to the best physicians, but to no avail.

“Finally,” Clarence writes of his daughter, “while she was in Chicago receiving treatment at the hands of an eminent specialist, she met someone who told her of Christian Science. She wrote home and begged my consent to her taking Christian Science treatment. My love for our daughter overcame my prejudice and preconceived erroneous notions and I wrote her that if there was anything in this world that would help her I wanted her to have it.”

A practitioner was engaged and began treatment, and within a few weeks Ella was well.

“She came home to us a new creature,” her overjoyed father reports, “and has been well and happy ever since.”11

Still, this didn’t convince him.

“For myself and for my family,” Clarence wrote candidly many years later, “I wished to feel very sure that I was not leaning upon a rotten staff.”

And so he applied his considerable intellect and investigative skills to the honest study of Christian Science, “its religious claims, its philosophy or metaphysics, its influences over human conduct and character, and its merits as a curative agency in the various ailments which are manifested in the body.”12

After thorough scrutiny, he would later tell a crowd of listeners, he became “firmly convinced of the absolute truthfulness and trustworthiness of the teachings of Christian Science.”13

An advocate for Christian Science

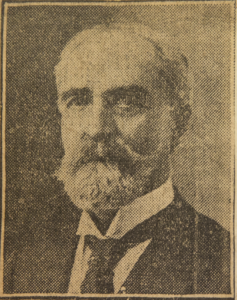

Clarence Buskirk’s legal training – his scrupulous nature, keen communication skills, and ability to reason analytically – would quickly prove to be an asset to the Christian Science movement.

In 1901, he was appointed Committee on Publication for the state of Indiana, and while serving in this role diligently responded to incorrect assumptions and misstatements about Christian Science in the press. The Muncie Times, Indianapolis Journal, Terre Haute Gazette, Richmond Sun-Telegram, Vincennes Commercial, and Goshen Democrat are just a few of the newspapers across the state that published Mr. Buskirk’s comments and corrections.14

Defending the constitutional rights of American citizens, particularly those practicing Christian Science, became a priority for him. In early 1901, when Indiana was considering a bill restricting the practice of any type of healing method outside the established schools of medicine, Mr. Buskirk watched the proceedings closely.

The Indiana Bill—which was specifically directed at Christian Scientists—outlawed the practice of healing without a license granted by the State Medical Board. A handful of Indiana Senators opposed the legislation, contending that it was unconstitutional and that it limited the “liberty of conscience” afforded to every person by natural law.15

“I would not abridge or limit the right of any man to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience,” remarked one senator, while the bill was being debated on the floor, “because it is a violation of the Constitution of the State of Indiana and the Constitution of the United States, and it is opposed to the very bulwark of freedom upon which our country stands.”16

Another added, “Why, my friends, all over this world wars have been waged, battles have been fought in the interests of liberty, religious liberty. . . . Tell me that liberty is to be voted away from the people of this country by an Indiana legislature! I resent it, my friends. I say that now and forever I protest against any act of this legislature that takes from me the right to worship God.”17

Despite such strong opposition, the bill passed. Clarence kept a sharp eye on the new legislation, relaying his own thoughts on the matter back to Boston, and ultimately to the rest of the field through the Christian Science periodicals.

“The good Samaritan who crossed the street to ‘relieve’ a fellow-being,” he commented in part, “can no longer be held up to our children in Indiana as furnishing a good example, but we must admonish our children that they become criminals if they fail to imitate the example of the Pharisees instead.”18

Eventually, Indiana Christian Scientist Emma Ehrit was indicted for “practicing medicine without a license.”19 Mr. Buskirk wrote a vigorous article around this time for the Indianapolis Journal. It begins, “Christian Science is a religion, not a method of practicing medicine.”20 After Mrs. Ehrit was tried before a jury and found not guilty (Clarence served as one of her attorneys), the proceedings and outcome of the case were once again recorded by Mr. Buskirk, and his report forwarded to the field through the pages of the Christian Science Sentinel.21

“The utter futility of attempts to curtail individual liberty through legislative enactment is once more apparent in the field of medical legislation,” the editors wrote in a brief introductory note telling of the acquittal.

Clarence explained the defense’s winning position in part: “Our contention was that the medical laws of Indiana, under the guarantees of our state constitution in favor of religious liberty, cannot be construed to mean that the clergyman, friend, or Christian Science practitioner who prays for the sick . . . disclaiming any knowledge or skill in materia medica, and employing no material means or methods, trusting solely in God for the recovery of the sick, is within the term ‘practising medicine’ as used in the statute.”22

A way with words

In addition to his legal acumen, Mr. Buskirk’s other great gift was his way with words. Already a widely-published poet and author before he became a Christian Scientist,23 his literary talents found a new outlet thereafter. Over 80 of his articles and 15 of his poems were published in the Christian Science periodicals, along with about two dozen reprints of articles originally written for other newspapers in his capacity as Committee on Publication.

On June 10, 1906, the dedication day of The Mother Church Extension, Clarence wrote an impromptu poem. That evening, when asked by reporters about his thoughts on the proceedings, he went silent, smiled, and handed them a copy of his words.

“The Dedication to Divine Love” was published in an array of newspapers and would be reprinted in the Christian Science periodicals as well. It begins:

In this brave city, after scores of years,

The stately sign of a sublime event,

The symbol and prophetic monument

Of men’s completer liberty, appears

With dominating dome against the sky,

A witness to this morning century.

The poem concludes:

And whose the voice, more eloquent and bold

Than Peter’s from his hermitage of old,

When Europe woke beneath his eloquence?

Whence is the voice, whose eloquence serene

And masterful evok’d this grandest scene

Of nineteen centuries? Its evidence

And message come to-day in words of cheer

And loving wisdom, while the thousands hear

In loving gratitude. A woman’s voice,

Sweet, earnest, pure, hath bade mankind rejoice

And waken from their falsehoods, and move on

Higher and higher yet, till “the good fight” be won.24

Mrs. Eddy wrote the author, “I beg to thank you for your contributions to our periodicals, they are doing much good. Your ‘Dedication to Divine Love’ is masterly. It comes nearer to Truth than history, it is both truth and history.” She asked if he had been present at the dedication, adding, “I think you must have done this in order to write as you did so extempore, so grandly.”25

Clarence responded with sincere gratitude.

“Yes, the lines – ‘The Dedication to Divine Love,’ – were written after attending the services, June 10th,” he replied, “an epochal day in the history of the Christian Science movement. . . . That they have merited the praise of the author of ‘Shepherd, Show me how to go,’ etc., makes me, indeed, most thankful and happy.”26

“Giving the world treasures of truth”

In April 1904, Mrs. Eddy appointed the “Hon. Clarence Buskirk,” as she called him,27 to the Christian Science Board of Lectureship. After being notified of Mrs. Eddy’s wishes, he wrote her, “I realize the great importance of the step; and I try to realize the magnitude and sacredness of the trust which is reposed in the Lectures. . . . I pledge my most earnest efforts to do what good I can in the field of Christian work which your noble and unwearying labors have plowed and planted.”28

Over the course of his lecturing work, Mr. Buskirk would receive much praise from Mrs. Eddy, who reviewed and read a number of his lectures. However, he got off to a rocky start. Mrs. Eddy was direct and to the point in her critique of his first lecture:

“[Y]our reasoning is profound and eloquent,” she wrote, “but your premise can afford no logical conclusion. . . . The extracts from your lecture disprove its title.” Ever the teacher, Mrs. Eddy pointed out its flaws for Clarence’s benefit, then concluded her remarks in part with, “I greatly desire to have you succeed and prosper in this sacred ministry hence these hints for your mile-stones.”29

Clarence, who had declared himself “glad to receive any critical suggestions by which I may improve my work in the good fight,”30 heeded Mrs. Eddy’s advice. Soon, she was lauding his efforts.

“The able discourse of our ‘learned Judge,’” she noted after one lecture he gave in Toledo, Ohio, “his flash of flight and insight, lays the axe ‘unto the root of the trees,’ and shatters whatever hinders the Science of being.”31

Another time, after reading one of his lectures printed in a newspaper, Mrs. Eddy wrote him, “I have yearned to write sooner and say, ‘well done good and faithful.’ Your lecture in Sandusky Register is indeed a gem. The lawyer, logician, and sound Scientist characterize it. You will give, are giving the world treasures of truth.”32

Clarence Buskirk’s lecture circuit took him from coast to coast and across the Atlantic to Great Britain, Germany, and France. From October to December 1905, he anticipated giving 19 lectures in seven states: Missouri, Kansas, Tennessee, Wisconsin, Iowa, Minnesota, and South Dakota.33 In early 1907, he lectured in New York, Michigan, Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Oregon, Washington, Nebraska, Wisconsin, Illinois, Kentucky, and Indiana. During his trip, he wrote Mrs. Eddy that the Cause of Christian Science was “growing as never before in its history. . . .”34

Later that same year, Clarence lectured in Belfast, Dublin, Berlin, and Paris, as well as some half a dozen other cities throughout Great Britain.35 One attendee described his first lecture in London, commenting on his “fine and impressive voice and manner with which it was delivered,”36 while another noted, “Mr. Buskirk got a magnificent reception, and he certainly deserved it. I have never heard such cheering at a lecture. When it was over the reporters jumped up and reached up to the platform to shake hands with him and congratulate him.”37

Praise for lecture and lecturer were manifold in the press, who called him “a thorough master of the subject,” “eloquent,” “most entertaining,” “a telling speaker” who “held his audience in rapt attention.” His lectures were noted as “wonderful,” “one of the best of its kind,” and his stage presence “held the undivided attention of his hearers.”38

Mr. Buskirk’s extensive lecturing trips were not easy for his family, who had to part with him often. Still, as his daughter Ella wrote to Mrs. Eddy at one point, “How much joy it is to know he is one among others chosen to speak for the right and defend our Cause and our dear Leader.”39

In 1915, Mr. Buskirk stepped down from the lecture circuit.

“I desire to be able to devote more time to the other general activities pertaining to the life of a Christian Science practitioner,” he explained, “and feel that in withdrawing from the lecture field I am only exchanging one line of activity and labor for other activities and labors in our movement.”40

Clarence Buskirk continued to serve the Cause of Christian Science until his passing in 1926.