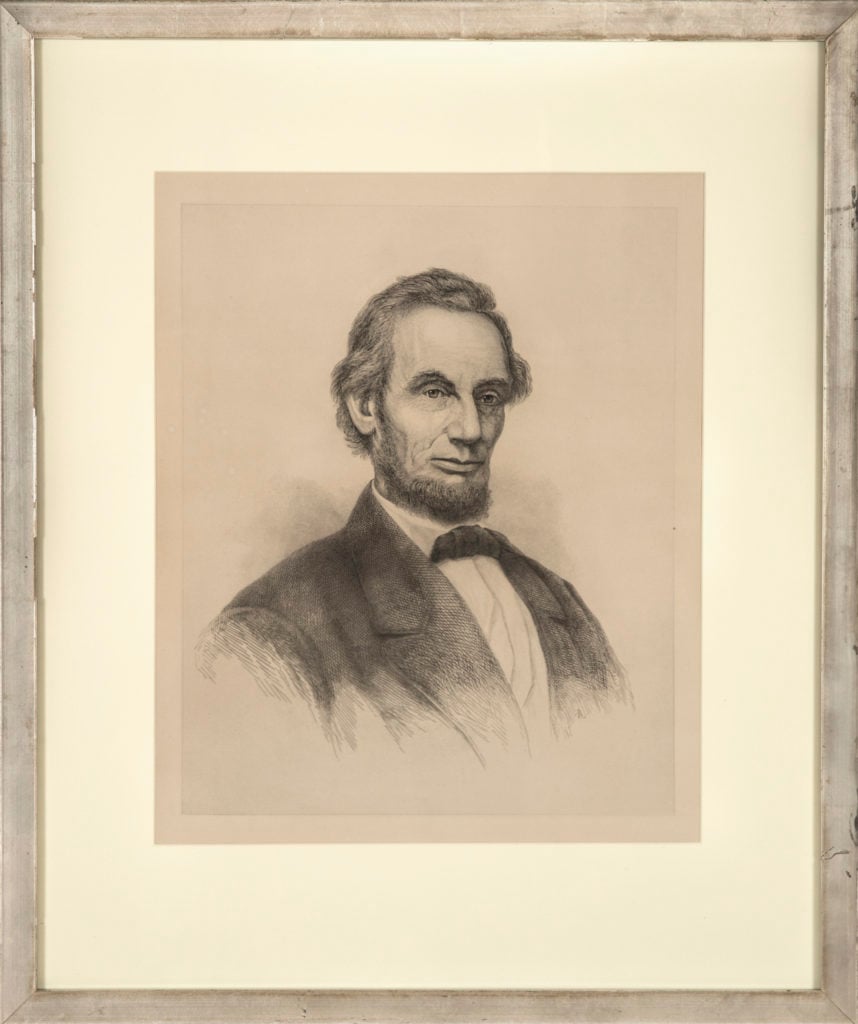

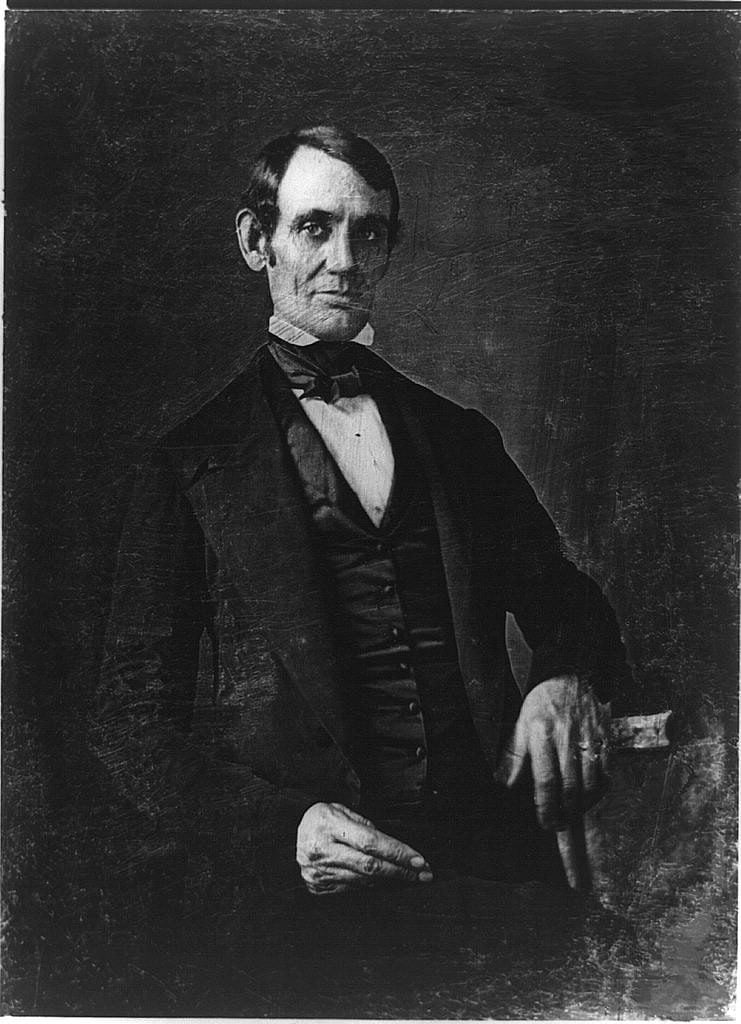

Abraham Lincoln made a lasting impression on many whom he met. This was certainly the case for William Ewing, who from boyhood was acquainted with Mr. Lincoln and who would eventually find his way to Christian Science.

Mr. Lincoln was a friend and frequent visitor of the Ewing household in the 1840s and 1850s. He was larger than life to young William, who would later describe the 16th President of the United States as a “transcendent composite of greatness and goodness, of genius and gentleness, of sublimity and simplicity.”1

In later years, William would recall how, as a boy, he heard Lincoln defend a case in court, where he delivered the “briefest and most logical argument that was ever made in a court of justice” in the state of Illinois.2 And in 1860, on behalf of his revered friend, William delivered a campaign speech in Muscatine, Iowa, during the memorable race to the United States Senate between Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln.3

Mr. Ewing particularly enjoyed telling friends and family about the time Lincoln came to visit and teased William’s father about his politics.

“Don’t let all these fine boys grow up Democrats,”4 the future president advised John Wallis Ewing, pointing to his five sons. “Let me make a Whig of one of them.”

Although a staunch Democrat himself, John thought his friend’s advice was a good idea for his son William. “You may take him,” he told Lincoln, who upon receiving the go-ahead hoisted the boy upon his knee and dubbed him “Whig Ewing”—a name that stuck to the youngster for many years to come.5

Another warm memory was the time William accompanied his father and Mr. Lincoln when the first “picture making machine” arrived in Bloomington, Illinois.6

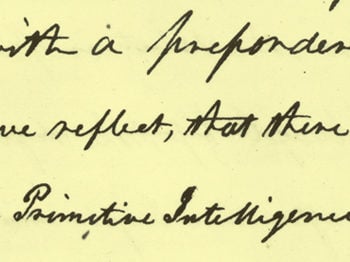

“The art gallery was a little room, perhaps 10 x 12 feet in size, over a little old-fashioned rhubarb drug store,” Ewing would write. “I went with my father and Mr. Lincoln over to this art gallery, across the street from my father’s house, to have their daguerreotypes taken. These pictures were very small and were worn respectively by Mrs. Lincoln and my mother as curio breast pins, and were regarded as very fine and rather striking likenesses.”7

“Abraham Lincoln’s massive character was constantly before the boy and the youth,” wrote one who would come to know William Ewing many years later, “and must have retained a large place in his unfolding manhood.”8

Proclivities toward the law

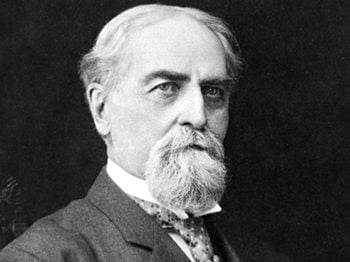

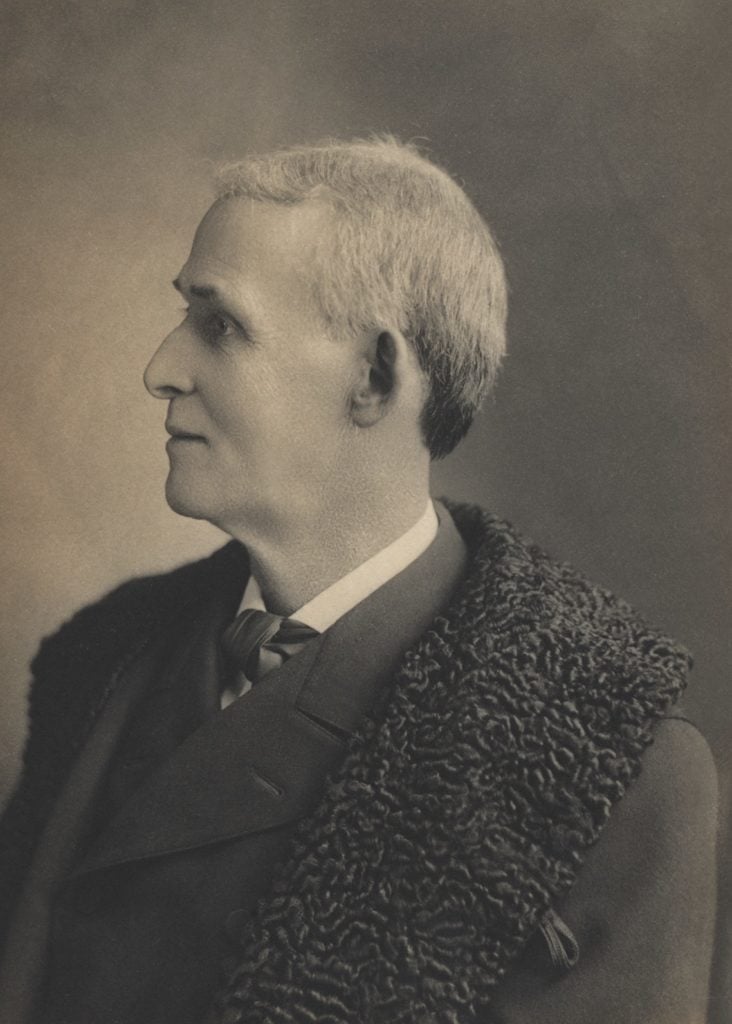

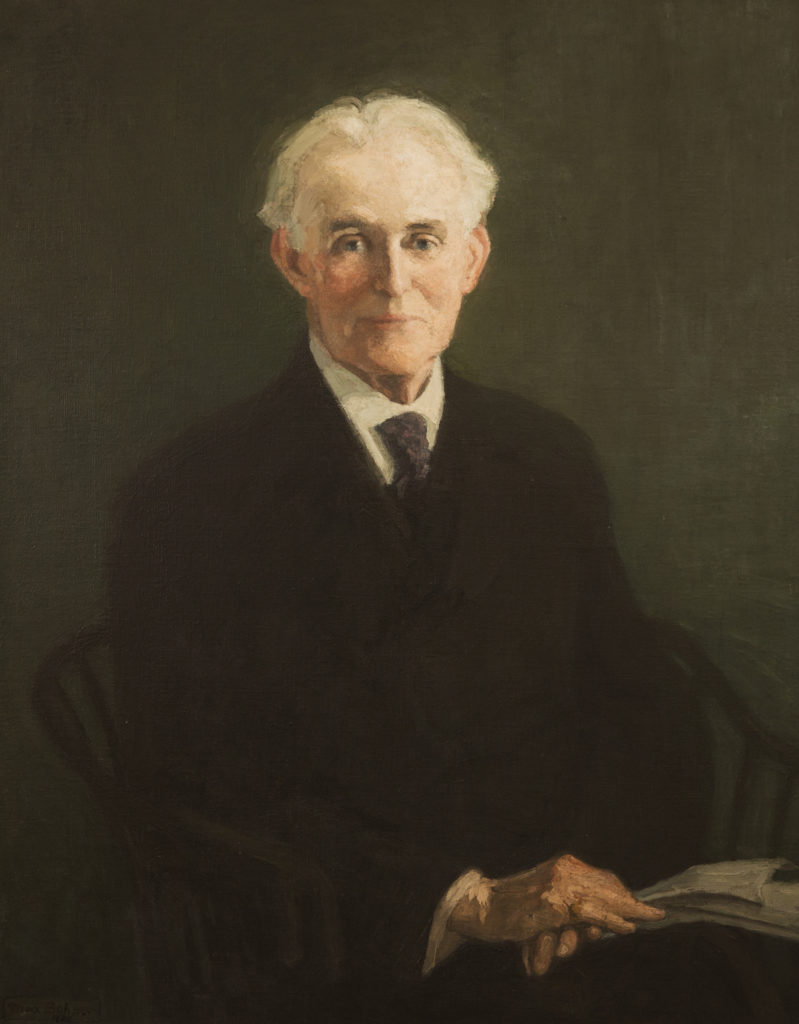

William Gillespie Ewing was born on a farm in McLean County, Illinois on May 11, 1839 to John Wallis Ewing and Maria McClelland Stevenson.9 After attending district schools, he studied at Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington until he began studying law in the office of Robert E. Williams at age twenty. He worked for the firm for three years, until he was admitted to the Illinois Bar in 1861. Work brought him to Quincy, Illinois, where for nineteen years he served at different times in the capacity of City Attorney, Superintendent of Schools, and State’s Attorney for the Judicial Circuit. It was during this time that he gained a reputation for his skill in handling several of the most notorious criminal cases.10

“Mr. Ewing’s uprightness, his love of his fellow-man, his firm belief in the ultimate triumph of the right,—these elements of character,” wrote an essayist, “together with a rare gift of eloquence, a fund of humor and practical experience, and a pathos which touches the hearts of men, fitted him to hold high rank, and as a trial lawyer and jury advocate he has had few equals and no superiors.”11

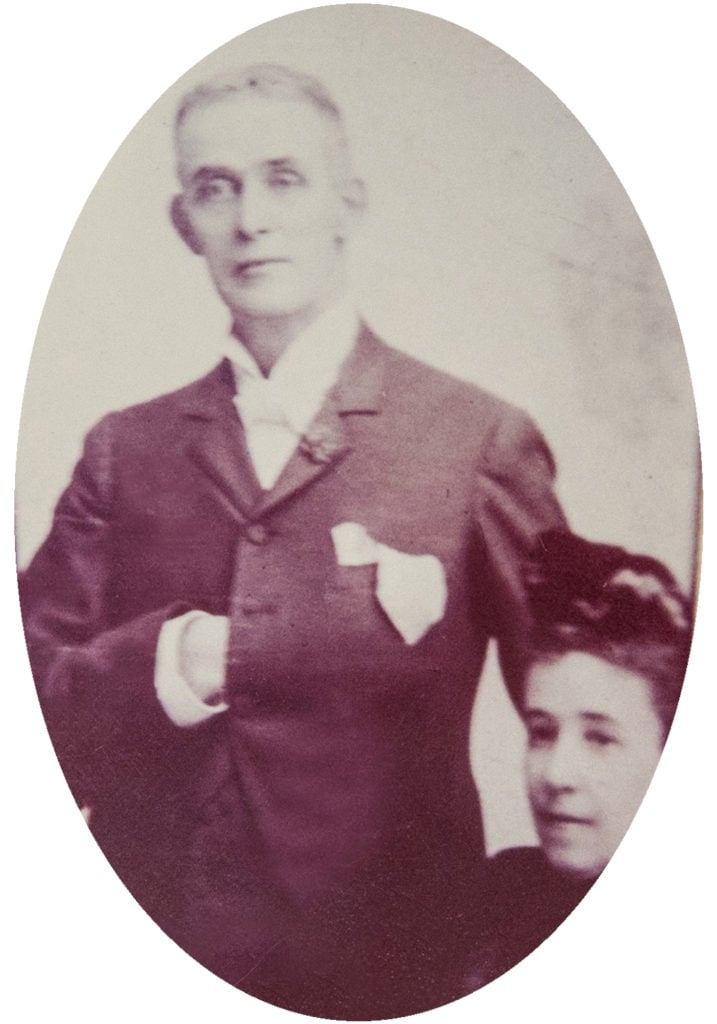

On April 25, 1865, William married Ruth Goodrich Babcock. Two years later, their first daughter, Mary (or “Mamie” as they called her), was born, followed by Ruth four years later.12

In 1882, William and his family moved to Chicago, and four years later he was appointed United States District Attorney for the Northern District of Illinois by President Grover Cleveland.13 Although he lost the candidacy for Congress from the First District of Illinois in 1890, in 1892 William was elected Judge of the Superior Court of Cook County, where he served six years.14

Judge Ewing was known for being “a gentleman of refined taste,” and for having “a courteous and kindly manner.”15 Those that knew him well loved him for his “gentle sunny spirit, as much as for the keen, incisive intellect.”16 He had “a national reputation as a lawyer of high legal attainments,” was “a scholar and an orator known far and wide,” and was “quoted all over this country as authority settling legal questions.”17

“Child-like surrender to Christian Science”

As an infant, William was baptized in the Presbyterian Church, and remained an active member into adulthood. His mother’s “sublime and beautiful faith in the measureless goodness of God” greatly impressed William, and after college he even considered going into the ministry.18

In 1884, when he was 45 years old, after suffering for many years from asthma and finding no relief in the care of the best physicians, William was told that unless he sought a change in climate, his illness would prove fatal. Upon hearing the news, William left home and hearth “with a sad heart” and journeyed “over the Rocky Mountains and across the Sierra Nevadas, and from climate to climate” throughout the country. Eventually, he found himself in Richmond, Virginia, nothing bettered, where a friend who had experienced a remarkable healing urged him to try Christian Science.

“I did not have one particle of faith in Christian Science,” he later recalled. “I did not know anything about it, did not care anything about it. My education, my habits of thought were all against it. . . .”19

Nevertheless, William finally agreed, and took a train to Boston to see a Christian Science practitioner. While meeting with her, a change swept over him.

“I felt a relief; and it was such a strange kind of relief,” he would later explain, “so gentle, so supremely sweet, as if a sunbeam had touched you in the dark midnight’s gloom; as if a finger unseen, dipped with life’s omnipotent power had touched you. . . .”20

William had not eaten anything except fluids for a month. He wasn’t able to walk 50 yards without stopping to rest, nor had he been able to lie down at night. But on the day that he visited the practitioner, all that changed.

“I never slept sweeter or more restfully and refreshingly in all my life,” he recalled. “I have not had a single attack of asthma or anything approaching it from that time to this. My healing was instantaneous, perfect and permanent. I am now able to go anywhere and do anything that an ordinary, respectable man would wish to do.”21

This healing, which came “in the very gloom and shadow of the grave,” moved William to later say, “I owe to Christian Science every breath I’ve drawn; and henceforth, all that I have or can, I will cheerfully contribute to give this dearest love of my life to my neighbor.”22

Fourteen years later, on December 26, 1898, he wrote a letter to Mary Baker Eddy, signing it, “a student of Christian Science.”23 Mrs. Eddy replied, “As I read the declaration of yourself . . . I thanked God and took courage. I need a modern Gamaliel, or doctor of the law – our Cause needs you, and God has given you to us.”24

Mrs. Eddy would also remark to a friend, “I was impressed with his sublime child-like surrender to C[hristian] S[cience].”25

“My lecturer laureate”

In 1899, William visited Mrs. Eddy at Pleasant View, her home in Concord, New Hampshire. While there, she asked if he would become a Christian Science lecturer. At first, the former judge didn’t think he had the ability that she was looking for. Referencing the Apostle Paul, he told her, “He is my ideal of the kind of man you want.” Towards the end of their conversation, however, William agreed to accept the position. “If you think that I will be of any value to you on the Lecture Board,” he said, “I will be very pleased to accept the service.”26

When William sent his first lecture to Mrs. Eddy, he hoped that she would feel free to use her blue editor’s pencil liberally. But when he received it back in the mail, the only words written in blue were: “Entirely satisfactory.”27

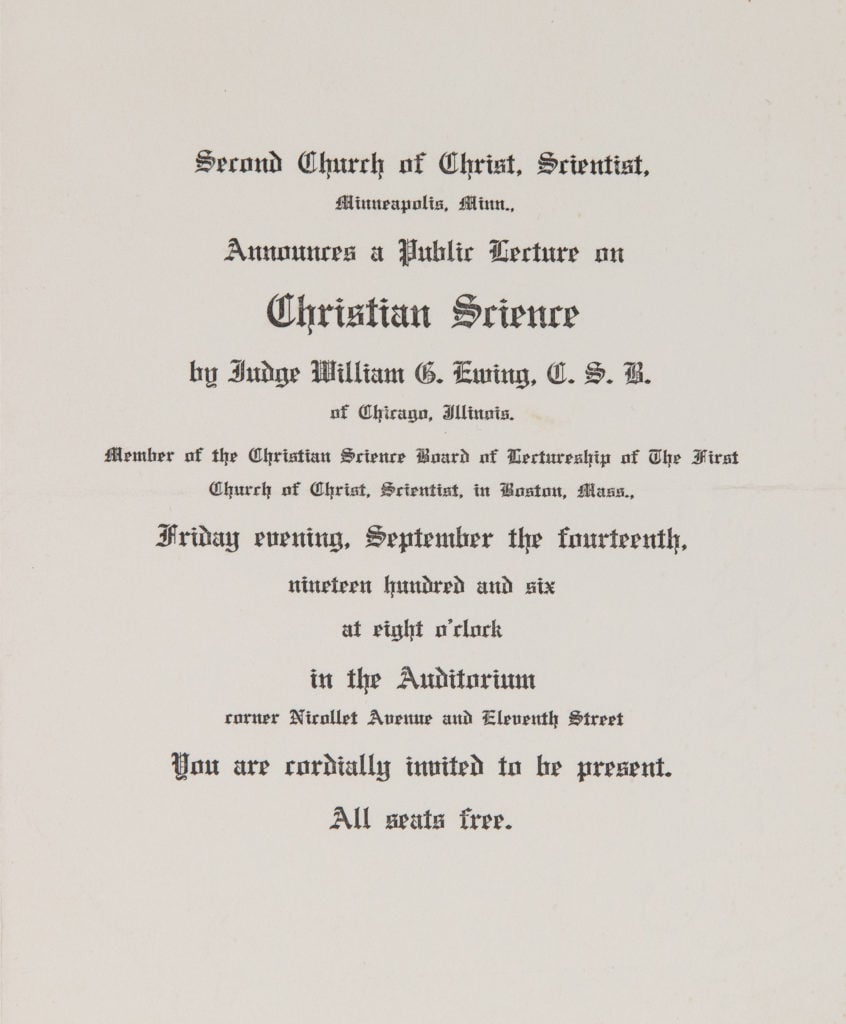

Once William decided to devote the rest of his life to Christian Science, he never looked back. Declining a re-nomination and re-election to the bench, he traveled from coast to coast and eventually overseas, lecturing constantly and continuously from 1899 until 1910.28 While he was originally slated to lecture only in the Midwestern section of the United States,29 he was on the Board for a mere six months when this notice appeared in the Christian Science Sentinel under the heading “Church Rule”:

“It shall be the privilege of all the leading Churches of Christ, Scientist, situated in our largest populated cities, or in the capital cities of the United States, Canada, or Great Britain (in addition to their other established lectures), to call on Judge William G. Ewing of Chicago, Ill., for an annual lecture under the regulations and auspices of the Mother Church in Boston.”30

On October 5, 1899, Hon. William Ewing delivered a lecture titled “Christian Science, the Religion of Jesus Christ,” in Boston’s Tremont Temple. It began, “I am not a preacher; not to soothe you into a brief dream of content by flowers of speech—I am a stranger to the pleasing, but ephemeral, devices of the orator; I simply want to talk to you as man to man, as friend to friend, brother to brother; my only art will be the simplicity and courage of conviction; my only argument, a statement of facts, and after all, how resistless is the potency of a fact! The sole purpose of inquiry in every court of justice in Christendom is, and ever has been, to invoke facts; the world is weary of theories, it longs for facts; it is surfeited with dogmas, arguments, and platitudes, and cries out for facts.”31

Mrs. Eddy was overjoyed with the lecture. After reading it through, she wrote William, “Soul of my Soul, the one God, spake through you. Your preparation of your hearers, your subject matter, your way of enforcing it by persuasive strength and humor, your exordium and peroration were perfect. No borrowed plumes, no confounding abstractions, no tiresome detail. And the fire of genius, honest convictions, stalwart purpose, all combine in that Lecture.”

She concluded the letter, “I have made you my lecturer laureate.”32

”Catching his fish”

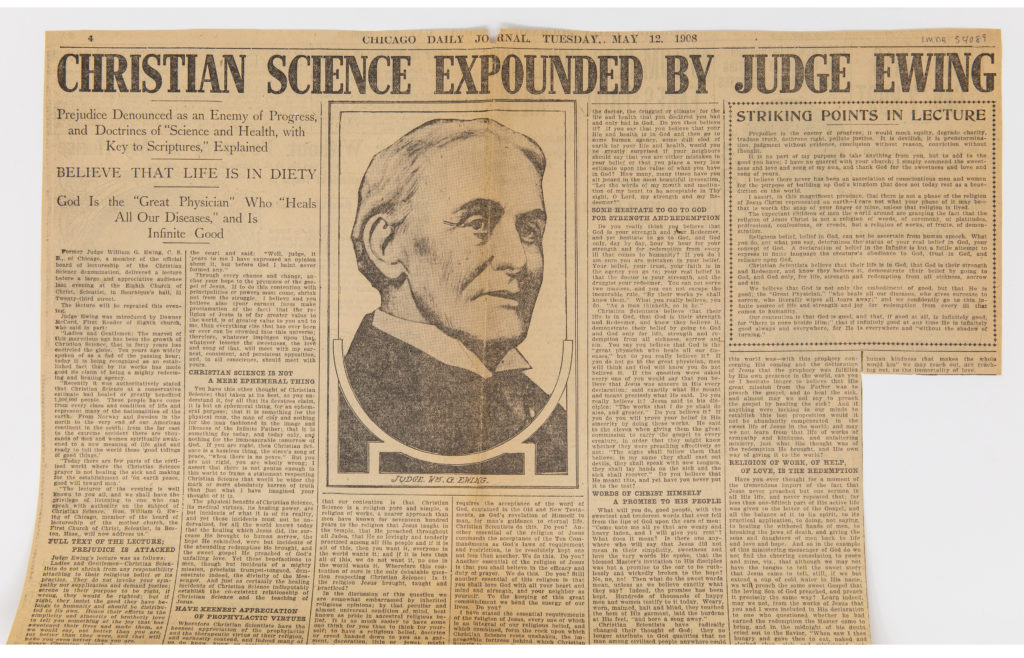

Described by one newspaper as “an elderly man, somewhat spare, of fine, scholarly appearance, an eloquent, impressive speaker, and a man who is evidently thoroughly in earnest,” Judge Ewing received high marks wherever he lectured.33

“One of the lecturer’s strong points is his deep sincerity, his honesty of statement and earnestness of manner,” wrote the editor of the Christian Science Sentinel.34 Praised for his mastery of his subject, his sound logic and superb rhetoric, he was known for neither criticizing nor proselytizing, but for endeavoring to enlighten. “It was not an argument to persuade to belief in the principles he represented, so much as it was a plea for fairness and candor,” observed the Memphis Commercial Appeal.35

Mrs. Eddy herself called Mr. Ewing “our best lecturer” on more than one occasion.36 She noted the spirit of “liberty, justice, divine wisdom, and love,” that radiated from his words, as well as his masterful clarity and concision.37

He “enters at the salient points of thought, thus catching his fish by the logic and love in Christian Science,” she wrote to a Christian Scientist in St. Louis in 1900.38 To another, she described him as “the soul of eloquence,” while to William’s wife, Ruth, she noted, “He is so adapted to waken thinkers to the call of God.”39

Continued service

In 1900, William Ewing lectured to a crowd in Quincy, Illinois, a city that knew him many years earlier as a lawyer and judge. Though the good-natured gentleman who left about the year 1880 was similar to the one who returned to give the lecture, this time, he had something more important to share.

“In changing from politics to religion,” he told the crowd, “I certainly cannot have offended my Republican friends, and in sacrificing my Democratic principles for religious principles I hope I have not offended my Democratic friends.”

“I am here to-day to discuss a question more important than any political question,” he explained, “a question the most important that could engage the thought of man in this advanced and advancing age; a question of vital importance to every man and every woman; a question than which none of more far-reaching importance has ever been presented for consideration. That question is, What is the relation of man to God, of the creature to the Creator?”40

This is a question that William Ewing strove to share with his listeners throughout his prolific career as a Christian Science Lecturer. In 1902, he made the first overseas tour of Great Britain by an American Christian Science lecturer.41 He would return again the following year, stopping in Ireland as well, and in 1904 was the first lecturer to visit Mexico.42

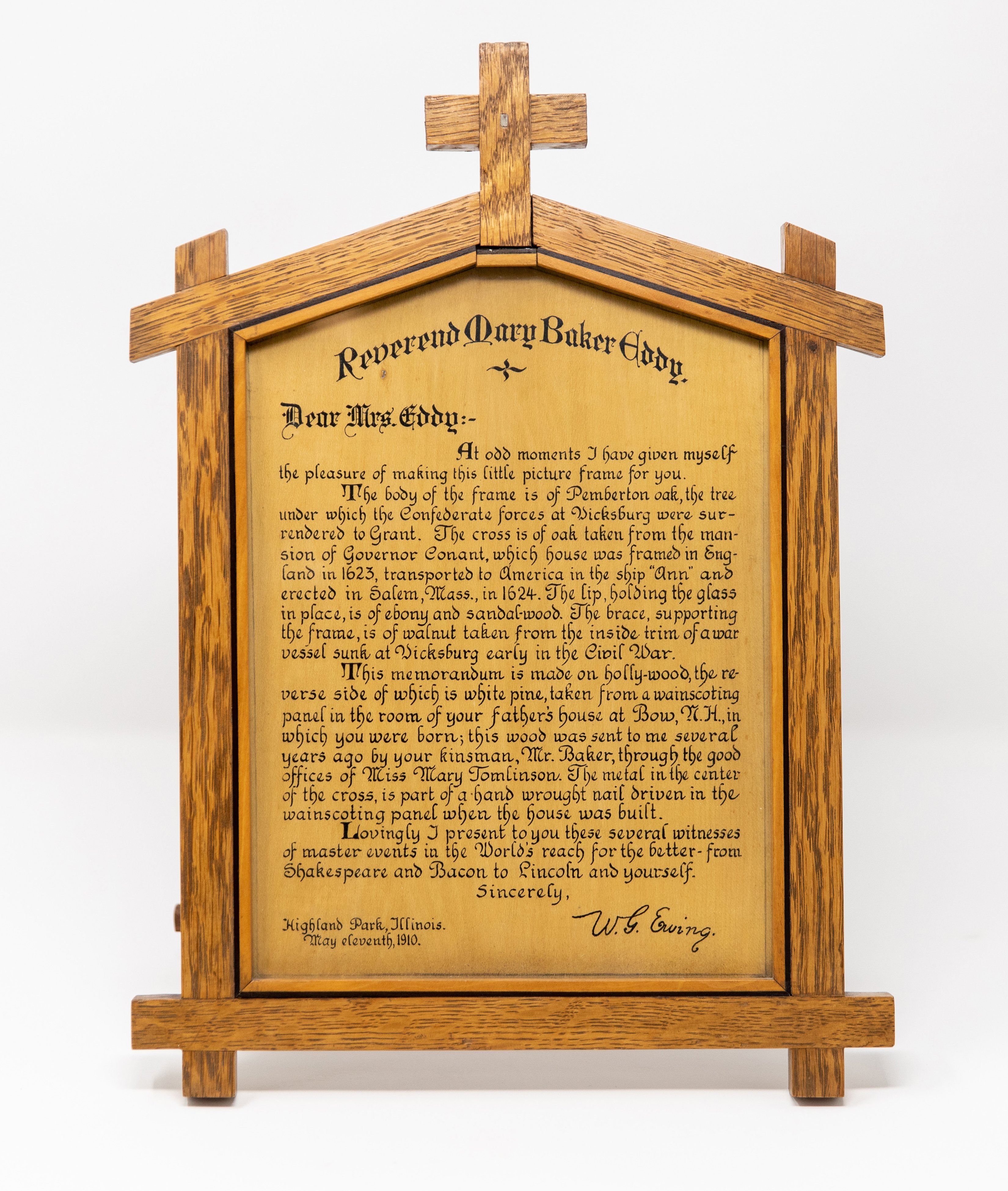

In addition to his skill as a lecturer, William was a talented woodworker, and in June 1910, presented a gift to Mrs. Eddy that he’d made in his spare time.

Irving Tomlinson, who was serving as one of Mrs. Eddy’s secretaries at the time, wrote a thank you note on behalf of Mrs. Eddy for the gift, to which William replied, “I beg you to express to Mrs. Eddy my great appreciation of the love and thanks she sent me by your hand. It gives me great comfort to know that I have been able to add one gleam of joy to her relentless struggle for the good of man.”44

“Judge and Mrs. Ewing of Chicago were always very dear friends of Mrs. Eddy’s,” Mr. Tomlinson later noted, adding that his “lovable qualities greatly endeared him to our Leader.”46

In November 1910, William G. Ewing stepped off the Board of Lectureship. In publicly expressing their gratitude for his years of active work – “work which he was well qualified to do by reason of his profound learning, ripe experience, and great love for his fellow-men” – the Christian Science Board of Directors concluded, “In the less public lines of Christian Science endeavor which will now engage his attention, Judge Ewing will be the same kindly Christian gentleman and retain the loving regard of all who know him.”47

Friend of Abraham Lincoln, distinguished judge, and eloquent advocate for Christian Science, this “kindly Christian gentleman” continued his endeavors in “the less public lines of Christian Science” until his passing on February 16, 1922.