J. ROBERT ATKINSON sat quietly on his mother’s porch with the California sunlight playing around him. To him all was dense blackness. Two months earlier he had been blinded by the accidental discharge of a pistol while he was packing it in his suitcase.

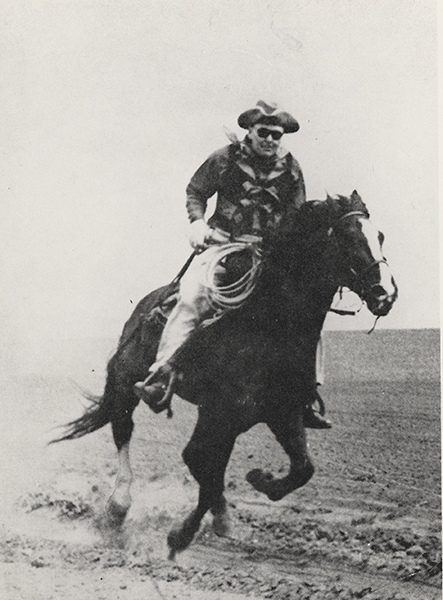

From his ‘teens he had been a cowboy — one of the best riders and cowherds in the Montana territory — a fearless and adroit bronco buster, a dependable and alert range rider. At the age of twenty-one his skill was recognized all over the Montana range and had attracted the attention of a leading cattleman in the area who, sensing his potential, offered him the most responsible post within his power to give — that of foreman of his large ranch. One condition was made: Bob must give up the social life of the saloon, the gambling and dance halls, where cowboys found their recreation. Bob loved his friends and his liquor and let the offered opportunity pass him by.

From the time he had become a Montana cowboy, after a hard but wholesome life on his father’s farm in Missouri, his work had been steadily climbing, always offering a new challenge and a new conquest. But life was drifting for him now at a dead level. He felt the need of visiting his mother who now lived in California. She had given him deep but gentle religious teachings — principles for living. It was while preparing to return to Montana that he had been blinded. For weeks after the accident he was held in the grip of despair, unreached by the loving help of his family who had rallied to his support.

A friend of the family — a Christian Scientist — urged him to attend church with her. At length he consented to do so but when the day arrived he deeply regretted his promise. The music and the singing made him acutely aware that never again would he see. In his own words, ” … I felt unutterably lost. Then something mother had said to me many times flashed through my mind, ‘When you need Him most, Bob, if you’ll just reach out your hand to God, you’ll find Him there, waiting to take yours.’ … in my extremity I did reach out, but I was very doubtful that God could see the hand of one who had paid Him so little heed for so long.” Gradually he heard the words of the soloist, “Mourner, it calls you ….” from Mrs. Eddy’s communion hymn, and he continues: ” … In that same moment, a ray of light suddenly flashed into my darkened consciousness, more beautiful than the sun and more wonderful than I thought ever would come to a human being …. At first I was only dazzled, breathless, even unbelieving. No, my sight had not been restored … at least not my physical sight. But, in that one instant, all the inner darkness which had so completely engulfed me was gone, and in its place was a radiant and inexpressible glory of hope and promise … no night remained and with the night, vanished all my forebodings of a dark, hopeless, helpless future…. Since that day in church until now (fifty-one years later) I have never been in darkness for a single instant, night or day. Indeed to me, ‘the night shineth as the day,’ quoting from the 139th Psalm.” He joined The Mother Church in 1915 and was a member until his passing in 1964. His wife, Alberta Atkinson, is still a member.

As Bob Atkinson sat on the porch that sunny morning his mind was filled with hope in spite of his personal darkness. A sightless huckster, bringing vegetables to the door, came this day with something for Bob — a Braille chart of the Moon system of raised printing and several pages from the Bible printed in Moon Braille. After his accident, the Atkinson family had rallied around him and took turns in reading to him through much of the day — mostly from the Bible. The old huckster explained to him how he could read for himself by using the embossed printing. The original Braille system was invented in 1829 by a young professor of music, mathematics, and history at the Paris School for the Blind — Louis Braille, who had been blind from the age of three. In time, several different adaptations of his system were made in England and America, each group working independently with no coordinated effort to meet the real needs of the blind.

When Bob Atkinson began to look for books in Braille to read, he was appalled at the meager number of them, at their lack of quality, and at the confused state of the Braille systems. In 1912 little beyond textbooks for children had been produced in America, and the few available adult publications were hardly adapted to raise the spirits of the sightless. Only one thing remained to be done, Bob reasoned. He must make his own library. He acquired a typewriter-like instrument for transcribing Braille and with the help of his sister Agnes, he made a list of books to be transcribed. Agnes was an experienced teacher and gave him untold help in the selection of books for his library, also in reading to him while he made transcriptions. She helped him with the various Braille systems and within eighteen months he had acquired a working knowledge of the New York Point system, the Revised American system, and the British system. Earlier he had mastered the Moon system.

In 1915 the Pan-American Exposition was held in San Francisco and during that time the first international conference to consider the establishment of a uniform system of raised print for all English-speaking peoples was held. This conference had been made possible largely by that “great-hearted” woman, Mary Beecher Longyear, who had given $5,000 toward its expenses. She had long been interested in helping the sightless. H. Randolph Latimer, Director of the Western Pennsylvania Institute for the Blind, and “one of the truly great figures in the world of the sightless,” presented a Braille system with British and American features which he proposed for acceptance by the conference. It was enthusiastically approved but, with no enforcement, sixteen years were to pass before a single system of Braille for English-speaking countries became a reality — not until 1931.1

Meanwhile, Bob Atkinson continued his transcriptions. He had learned independence of bodily movement and how to stand alone in a world of darkness, and when a great desire to help his fellow travelers in the dark overtook him, he was able to go alone from El Centro, California, where his mother now lived, to Los Angeles and to begin his work there. Soon he was teaching other sightless adults to read Braille and to rise above such despair as had once engulfed him, helping them to find hope again and faith in God.

After his move he continued to build his library. In four years he had transcribed 960,000 words in Braille, bound in sixteen volumes. They included all the fundamentals of a liberal education.

In 1918 Mr. and Mrs. Longyear went to Pasadena to spend the winter. Miss Maurine Campbell took them to see Mr. Atkinson’s library. They were deeply moved by his accomplishment and listened with sympathy when he told them of the deplorable lack of reading matter for the sightless, and especially of the urgent need for the Bible in a uniform Braille system. A few days later Mrs. Longyear called on Mr. Atkinson again and said to him: “I had heard about you before I came West …. I believe you are the man to produce the Bible in Revised Braille. I’ll go further than that. I believe you are the man to establish a Braille printing establishment for the purpose of producing books in necessary quantity for sightless readers. If I make it possible, will you do it? … If you will undertake it, Mr. Longyear and I are prepared to contribute $5,000 a year for five years toward the establishment and operation of a Braille printing plant such as I have mentioned, with the stipulation that the Bible shall be the first work you publish. It would be specified that $3,000 of each yearly contribution shall be your salary. Will you do it?” For some weeks he considered seriously the problems of operating a non-profit business and the personal sacrifices this would entail but, aside from personal considerations, he knew that Mrs. Longyear’s offer gave him the greatest opportunity to help the greatest number of his sightless companions in the dark. He realized that for this he had been preparing himself. In February 1919 he advised her that he was prepared to accept. (When the Longyear gift terminated in 1924 Mrs. Longyear had contributed $34,000.)

Having made his decision, Robert Atkinson was galvanized into immediate action. He set out in February for the East to investigate existing machinery for printing Braille manuscripts. He went by way of Detroit where he had wired Miss Alberta Blada, whom he had met at a Los Angeles Christian Science church meeting, and who spent some time with him as a volunteer secretary. In 1919 she had returned to visit her family in Wisconsin prior to moving permanently to California. Bob had realized that she was the girl he had always looked for, but had never felt that he was in a position to speak to her. The matter was quickly settled when they met at the station in Detroit. While he stammered his proposal, she laughed and said, “Just why do you suppose I came here in such a hurry to meet you?”

“Then, let’s hurry together,” he happily replied. They were immediately married and from that day she was his supporting eyes and hands and mind, sharing with him the great work toward which together they were hurrying that day in 1919.

Their visits to New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C., were disappointing. They soon found that no equipment for printing in Braille was made commercially in New York or elsewhere. In New York, they spent long hours in the Matilda Ziegler Magazine plant examining every detail of the press and stereotyping machines. This was the only plant in New York printing in Braille, and the only magazine of a secular nature printed in the United States for the sightless. All the machinery was handmade and they found this to be true of the Howe Memorial Press of the Perkins Institute for the Blind near Boston, and the American Printing House in Louisville, Kentucky, where textbooks authorized by Congress were printed for blind children. The library for the blind at the Library of Congress was also a disappointment. In a single small room they found mainly textbooks for children and a few shelves with adult literature — mostly ponderous and steeped in gloom. In Baltimore, they visited the Evergreen Hospital No. 7, where he gave new hope to soldiers blinded in the First World War. He was greeted with loud cheers when he assured them of his plan to produce books of interest to them. Their enthusiasm and need sealed his decision that day to devote himself to this work.

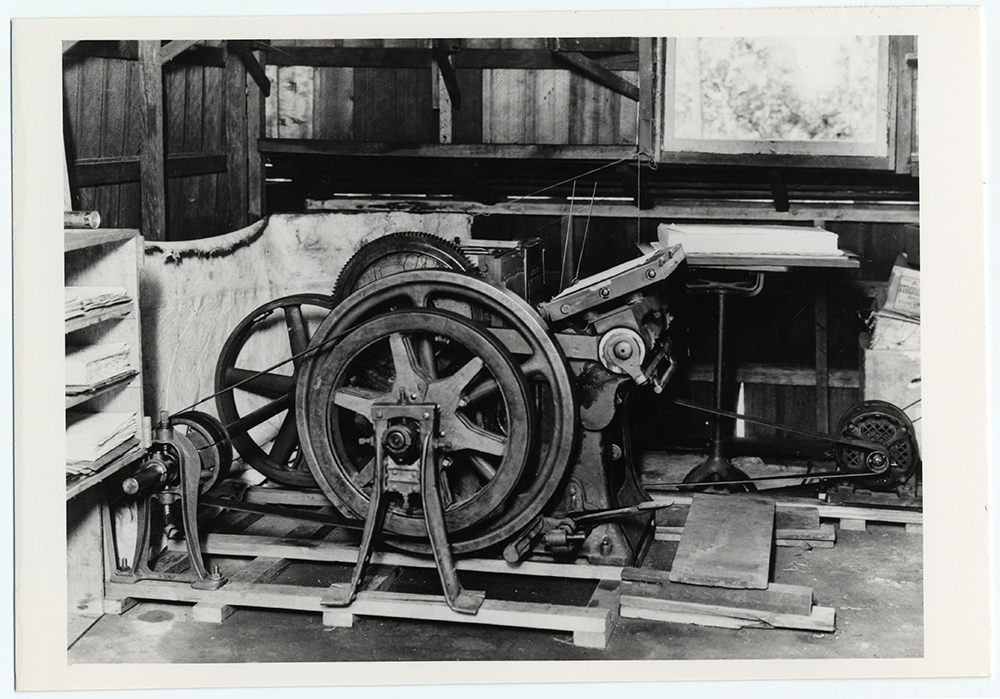

Back in California at the end of March, Mrs. Atkinson found a roomy Swiss chalet-type house near Hollywood with a two-car garage which became the press room. Eventually the entire plant was set up in the house and was operated there until 1926 when the rapid expansion of the work required a number of moves which led them in 1927 to acquire the property at 741 North Vermont Avenue in Los Angeles, its permanent location.

But, going back to 1919, machinery for the project must be built, and Bob Atkinson set out to make the best equipment yet known for Braille printing. A skilled mechanical engineer, Harry Gearing, came to work with him and together they completed the press in eighteen months. It was patented in 1921. Meanwhile, Bob turned his attention to the manufacture of a paper with maximum tensile strength, which would withstand repeated finger-tip readings over the years. The Zellerbach Paper Company of San Francisco cooperated with him in experimenting with various paper formulae and they arrived at one which later was adopted by the United States Bureau of Standards for use by the Library of Congress in printing literature for the sightless.

Mr. and Mrs. Atkinson organized a company and incorporated it under the name of Universal Braille Press. The printing of the King James Version of the Bible in Revised Braille was their first undertaking. In 1923 the New Testament was ready and in 1924 the complete Bible was available in twenty-one volumes printed on one side of the paper which measured 12 inches high by 14 inches wide. Although printing on both sides of the paper had long been discussed, it remained for Bob Atkinson to devise a system of spacing and contractions, called interpoint, to make it possible. In 1928 another King James Version of the Bible was brought out, printed on both sides of the paper in British Braille, thus reducing both cost of production and weight of the finished edition.

In 1924 the Braille Press received an order for the largest single edition of any book ever brought out in raised print: 2,500 volumes of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy for The Christian Science Publishing Society. The printing in Braille of the Christian Science Lesson Sermon was later placed with the Universal Braille Press, with repeat printings in subsequent years.

From 1919 to his retirement in 1957, scarcely a year passed in which J. Robert Atkinson did not make some technical, mechanical or social contribution for the benefit of sightless people. From 1921 he was an active member of the American Association of Workers for the Blind and served as an officer, including four years as President. To their biennial meetings he brought his inexhaustible ideas. He was a charter trustee of the American Foundation for the Blind, a central coordinating committee for united effort throughout the United States. He was early aware of the part Government must play in serving the sightless.

In all of J. Robert Atkinson’s work he was to express a universal sense of love, enabling him to provide the basic equipment by which the blind could help themselves. Far-reaching in its effect was his publication of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Dawn of a Tomorrow, a lighthearted novel, the first of many to come, designed to lighten the darkened thought of the sightless. In 1926 he began the publication of the Braille Mirror, a monthly magazine modeled after the editorial format of the Reader’s Digest; and from 1931 to 1939 he developed the equipment for printing books in Moon type and issued The New Moon for those lacking finger tip sensitivity. In 1938 he published jointly with the American Printing House the complete Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, and in 1948 he brought out Anthology for children. But he felt more must be done for the individual. The sightless must be prepared if he were to find his right place in the world.

“We will have to do something about that,” he said to Mrs. Atkinson. She agreed, adding, “We weren’t ready to undertake it before. I think we are now.” By 1929 the idea had taken form.

At the biennial meeting of the American Association of Workers for the Blind in 1929, Mr. and Mrs. Atkinson announced a plan to consolidate the Universal Braille Press and all its assets into a non-profit, non-sectarian corporation dedicated to the welfare of the blind without respect to race, color, or creed. It was to be known as Braille Institute of America, Inc. The plan was wholly that of Mr. and Mrs. Atkinson and developed out of their understanding of the still urgent needs of the sightless. While the printing breakthrough was fundamental, they saw that now they must provide a program of education and social culture if the sightless were to take normal places in society. They must learn to play, to adjust to life’s countless hazards; they must learn trades, crafts, and the use of the mind.

The transition from private ownership of the Universal Braille Press to a public institution governed by a Board and publicly supported was accomplished easily. The promise for the immediate future was bright. Then came the depression. The Atkinsons were not at a loss, however. If 1931 was the nadir of the American economy, it was to prove a time of great blessing to the sightless. Mr. Atkinson initiated a move for Government support through a California congressman, which eventually resulted in passage of the Pratt-Smoot Act, providing an annual fund of $100,000 to be administered by the Library of Congress for making books in raised print for the sightless. These were to be distributed throughout the country from designated library centers. The Braille Institute under the direction of Mr. Atkinson established a free public library at the Institute with 250 titles in 1 ,350 volumes and a few periodicals. Later this library was made the distributing center for Southern California and Arizona. A final blessing came in 1931 with the adoption of a single system of Braille- British Braille with many added contractions — for use in all English-speaking countries.

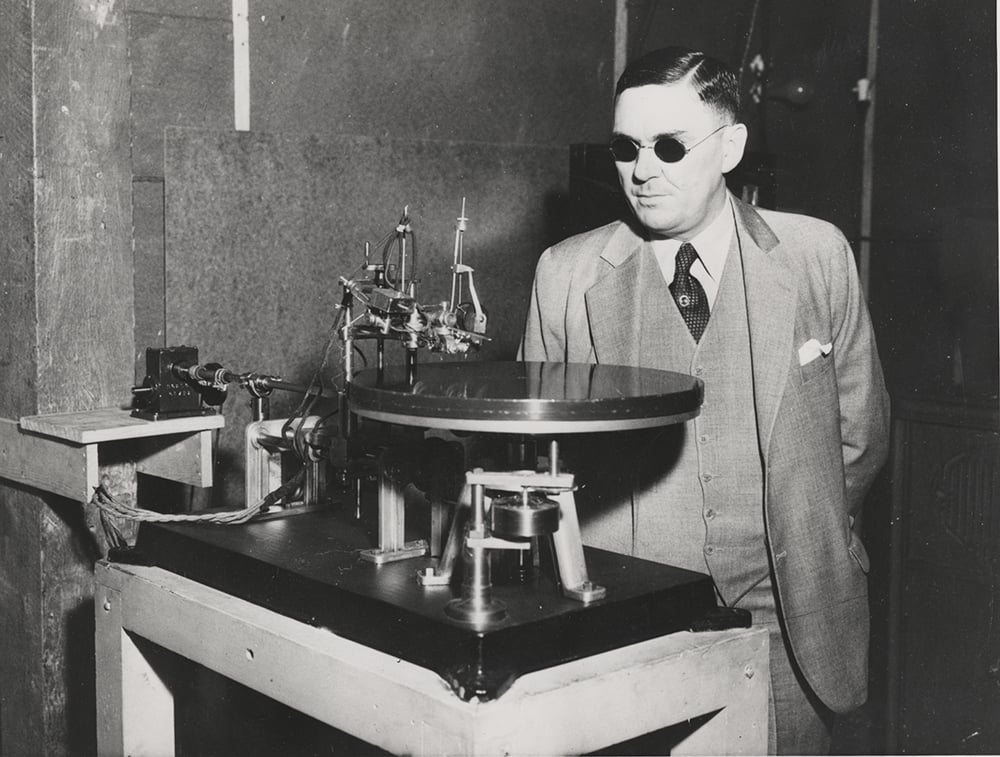

Mr. Atkinson then turned his thought to the last segment of the sightless still in need — to those who were unable to read Braille because of insensitivity in the finger tips or crippled hands. The possibility of the spoken recordings, just coming in to use, came to him as a solution. He applied himself to the problem and discovered a constant speed principle which he embodied in his invention called the “readaphone,” with forty-five uninterrupted minutes of listening on each side of the record. While the invention was not adopted by the Government for the Library of Congress, it stimulated the introduction of records into its collection for the blind. They number in the thousands today. About that time he also designed and engineered a portable Braille writer which was patented in 1934.

After the depression faded in the mid-thirties, Robert Atkinson’s many friends in business circles and in the Hollywood community began to pour contributions into the Institute, and an era of expansion began under his far-seeing direction. He was considered by many businessmen to be one of the “most useful” citizens in the state and the nation. In the next few years he was to see and direct, under his friendly Board, the fruits of his long years of work. He was to see the introduction in private homes of individual teaching of Braille; the initiation of classes in crafts, trades, theatre and dancing, literary training, teaching; a thrift shop was added, and the Atkinson Auditorium dedicated in 1953.

When he retired in 1957 after forty-five years of service he was awarded the honorary Shotwell Memorial Award and Scroll for distinguished service to the sightless as a member, director and officer of the American Association of Workers for the Blind, and as Founder, Vice-President, and Managing Director of the Braille Institute of America, Inc.

A handsome nine-foot bronze monument to him, with his horse Sandy, stands at the head of a clear lake in Cascade, Montana; but his imperishable monument is the institution he founded and developed, and the host of joyous, sightless individuals who have been and continue to be blessed by his inspired dedication and the dauntless devotion of his beloved wife.