THE NEW ENGLAND PAINTER, James Franklin Gilman (1850-1929), is of special interest to Christian Scientists because of his illustrations for Mary Baker Eddy’s poem, Christ and Christmas. A deeper understanding of the artist’s life and his experience in making the illustrations for the poem throw an interesting light on this important publication by Mrs. Eddy.

When James Gilman began his work on Christ and Christmas in March 1893, a poetic temperament, a rejection of materialistic motives in work, and a devotion to Christian Science and Mrs. Eddy, were already at work in his consciousness

His life purpose really emerges about 1870 when he was some twenty years of age. By that time he had determined upon “art-practice” as his life work and looked back on his earlier years only to recall that “a vague, nameless sense of lnfinite Beauty attended his thought from childhood,” and his awakening in his late teens to the need of giving tangible expression to this thought that would unfold in some appropriate and practical form.

The choice of his life activity seems to have been met in a natural way. A friendly neighbor in his home town, recognizing his skill in drawing, offered to pay him if he would make a drawing of his home for him. From this early suggestion may have come the greater part of James Gilman’s paintings, now so prized by descendants of many well-to-do farmers in northern Massachusetts and Vermont. By nature or necessity he was a nomad and for over fifty years as an artist, he never acquired a home nor accumulated material possessions, so far as is known. For much of his life he moved from place to place, and many times in return for room and board with a family he painted the homestead and its surroundings, usually including in the picture members of the family at their habitual occupations.

In 1970 Edyth Overing wrote in the Orange Enterprise and Journal, Orange, Massachusetts, on the occasion of an exhibition of Gilman’s work in New Salem, Massachusetts, “The viewer sees examples of country life as it was lived then … The whole family, including the animals, appear in many of the pictures … The paintings evoke a kind of nostalgia — the kind of homesickness which remembers perfection that never was.” She concluded, “In the work of James F. Gilman, artist, the past is preserved for all time.” Steven Preston of the Worcester Sunday Telegram, covering the same exhibit, wrote of Gilman’s work, “He pictured country life as idyllic and innocent, with man and nature in harmony.”

Mr. Gilman’s practice of signing and dating his pictures has been of utmost help in following his migrations over the years. His earliest known drawings are signed 1871 and 1872 and are in the collection of Mr. Charles E. Stearns of Billerica, Massachusetts. They are mostly in charcoal, stiffly drawn as if he were following rigid instructions from an early teaching manual. But this style apparently did not satisfy the artist’s desire to express in his work a sense of life in nature to which he had been sensitive from early childhood. One can well imagine his throwing away the teaching manual and turning within himself for the message that nature always gave to him. He taught himself the effective use of many media, including oil paints and etching, water colors and pastels, producing pictures which evidenced the self-discipline so essential to success in any endeavor. He was listed as instructor in drawing and painting at Goddard Seminary, Barre, Vermont, in the school catalogues of 1876 and 1877, and possibly he taught in 1878, but no catalogue of that year has been found.

The vicissitudes of his life as an artist called for certain “religious ethics,” as he termed it, the seeds of which had been sown in his childhood by an “earnestly Christian mother.” This awakening moral sense, together with his natural simplicity of thought, prepared him to accept Christian Science which came to him in 1884. At the time he was living, teaching and practicing his art in Montpelier, Vermont. He had come to this town about 1880 and had published, the following year, his pamphlet, Instructions in Pictorial Art for Home Study. It seems likely that he maintained a studio for some years in Union Block, Main Street, where in 1884 he advertised to make portraits from small pictures.

After learning of Christian Science he turned seriously to the study of the Christian Science textbook, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy. He records that he was soon enabled to find in its teachings the healing power of God, and to discover through it the spiritual explanation and import of his early ideals. He continued his art-practice in Montpelier until 1892, when he was led to go to Concord, New Hampshire, “in obedience solely to his spiritual intuition that it would be spiritually good for him to do so.”

Within three weeks after arriving in Concord, he had arranged with Mr. Bowers, Mrs. Eddy’s photographer, to make some preliminary sketches for an exterior picture of Pleasant View “that was required.” When completed Mr. Bowers took them to Pleasant View to show Mrs. Eddy. It was about the year’s end and Mrs. Eddy invited Mr. Bowers and Mr. Gilman to visit with her on New Year’s Day. Mrs. Eddy talked freely to them on the subject of Christian Science until eight o’clock. Later Mr. Gilman was to be frequently called to Pleasant View, and often remained for lunch and dinner. Copies of the prints made from two of his early drawings of Pleasant View are hanging in the Mary Baker Eddy Museum.

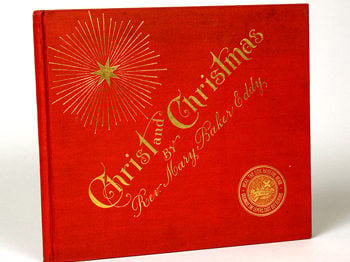

On March 11, 1893 Mrs. Eddy invited Mr. Gilman to come to see her, and asked him if he would make illustrations for a poem, Christ and Christmas, which she had written. She cautioned him to say nothing about this plan. Later she asked him if he knew how to keep a secret. “Let no one know you have a secret,” she is reported to have said, “and you can keep it.” Mrs. Eddy is said to have told him his mentality was “uncommonly plastic and impressible” and she urged him to maintain a purity of thought, free from the suggestions of other minds, that his thought might be receptive to the spiritual import of her poem. His early drawings for Mrs. Eddy met with high favor and on occasion she sent him home with “God bless you.” During the time he was making illustrations for Christ and Christmas he kept a diary. He reported the difficulties of preparing his work and some problems of his own making which brought down upon him rebukes from Mrs. Eddy.

Every illustration was completed under Mrs. Eddy’s supervision and was designed to express the spiritual idea embodied in her poem. He saw that out of his limited understanding alone he could not make illustrations acceptable to Mrs. Eddy. The design must come from pure inspiration to attain Mrs. Eddy’s vision. His devotion to her ideal helped him to reach a point of inspiration. However, he later said that “every footstep forward cost numberless pangs, which appeared to my sense then, of course, more than heaven was worth.”

When planning the picture “Christmas Morn” Mrs. Eddy wished to have angels swiftly moving through the air to welcome the dawn, but without wings. For some four days he struggled with the composition but when he brought it to Mrs. Eddy she was dissatisfied with it. A note arrived from her after he had begun to rise from his subsequent depression. He went in his “freshly attained chastened sense” for a walk to Bow Mills about the time of sunset. He said that the “sundown rays” streamed through (the break in the clouds) causing “a sharp cupola that was on a building just in line with me and the sunset rays of light, together with some beautiful trees, to appear silhouetted against the light western sky in a very picturesque, artistic way.” In this scene he found the inspiration needed to complete satisfactorily the illustration “Christmas Morn,” which included “for beauty’s sake” a domed building on the horizon.

Christ and Christmas was published in December 1893 with two editions of 1000 copies each, the first printed in black ink, the second in sepia. When an early copy was shown to Mr. Gilman by Mrs. Eddy, he was surprised and pleased that his name appeared jointly with that of Mrs. Eddy as artists.

In the latter part of February 1894 James Gilman decided to go to Gardner, Massachusetts, and there, in collaboration with H.E. Carlton, an illustrated album, PLEASANT VIEW, Home Surroundings of Rev. Mary Baker Eddy, was brought out in August 1894. Twenty plates included in it show exterior and interior views of Mrs. Eddy’s home. They combine drawings by Gilman with photographs by Bowers, reproduced by photogravure. Mr. Carlton, a photograveur, had made the plates for Christ and Christmas. Later he and Gilman collaborated in a reproduction of Gilman’s charcoal painting of “The Beautiful Bettie’s Spring Wood” on the Westminster Road. Still later Gilman issued an annual Christian Science calendar for the years 1901, 1902, and 1903.

In the latter part of the 1890’s Mr. Gilman was actively working to establish Christian Science in Athol, Massachusetts, and nearby Orange. As recorded under Church Services in The Christian Science Journal, he was serving as First Reader in Athol in August 1900 and continued through December 1902. He had earlier received class instruction in Christian Science.

In 1904 he issued a leaflet, Gilman’s OLD HOME PICTURES, from 80 West Main Street, Orange, in which he stated his sense of mission as an artist. He wrote, “Life abounds in the poetry of beauty … eyes that can see beauty are a great possession, and the true art-usefulness lies in its power for opening eyes more and more to see life’s beauty in the true and real that is all about us … ” He felt it was important to preserve pictorially New England life as it was in his time.

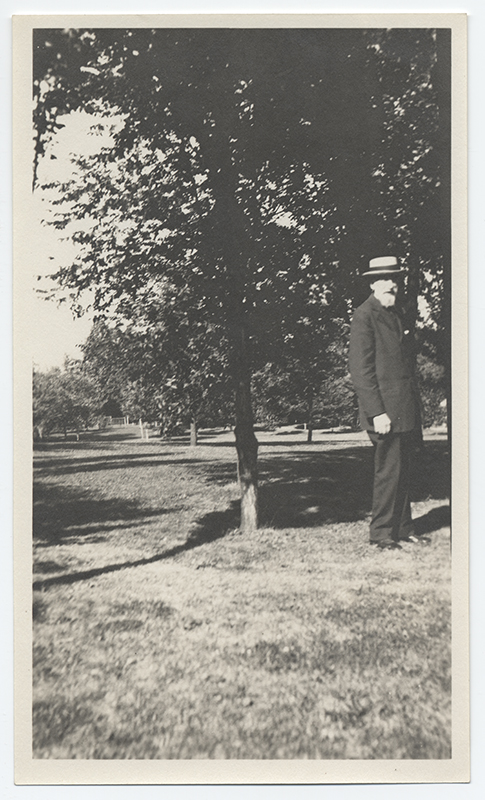

By 1905 he was making portraits and pictures of the countryside in New Salem, which was not far from Orange. In 1910 the graduating class of the New Salem Academy bought from Mr. Gilman one of his paintings to give to their favorite teacher. A member of the class, Hugo Karlson, recalled a few years ago that he often saw Gilman while he was a student at the Academy. Karlson’s image of Mr. Gilman was included by Mrs. Edyth Overing in her brochure for the Gilman Exhibition held in 1970 by the Swift River Historical Society, New Salem: ” … He had gray hair, was tall, slender, and quite dignified… He wore a long, swallow-tail coat, which was not considered unusual, and a white shirt … He had long, pale, slender hands (unusual to us because all farmers’ hands were brown) … His clothes looked worn … He sounded educated, was well-mannered and never used coarse or abusive language. He had a friendly disposition, a mild man… ” Mrs. May Waterman of Athol, who was with him just before his passing, spoke of him on April 13, 1972 as a man of great pride, scrupulously clean, and one who loved people, especially children.

On July 3, 1920 Mr. Gilman came to Boston from Athol, where he was then living, to see Mrs. Longyear, a visit she records in her diary of that date. She met him at the train and picked him out of the crowd at once. He was extra tall, wore a blue serge suit, had a gray beard and mustache. He told Mrs. Longyear much of his experience with Mrs. Eddy when making the illustrations for Christ and Christmas. In her diary she records his mention of the illustration “Christian Science Healing.” When at work on it he said to Mrs. Eddy that he thought the healer should express repose and calm, but Mrs. Eddy is said to have answered, “Yes, but Love yearns.” Mr. Gilman spent the night at the Longyear home and next morning she took him to the train.

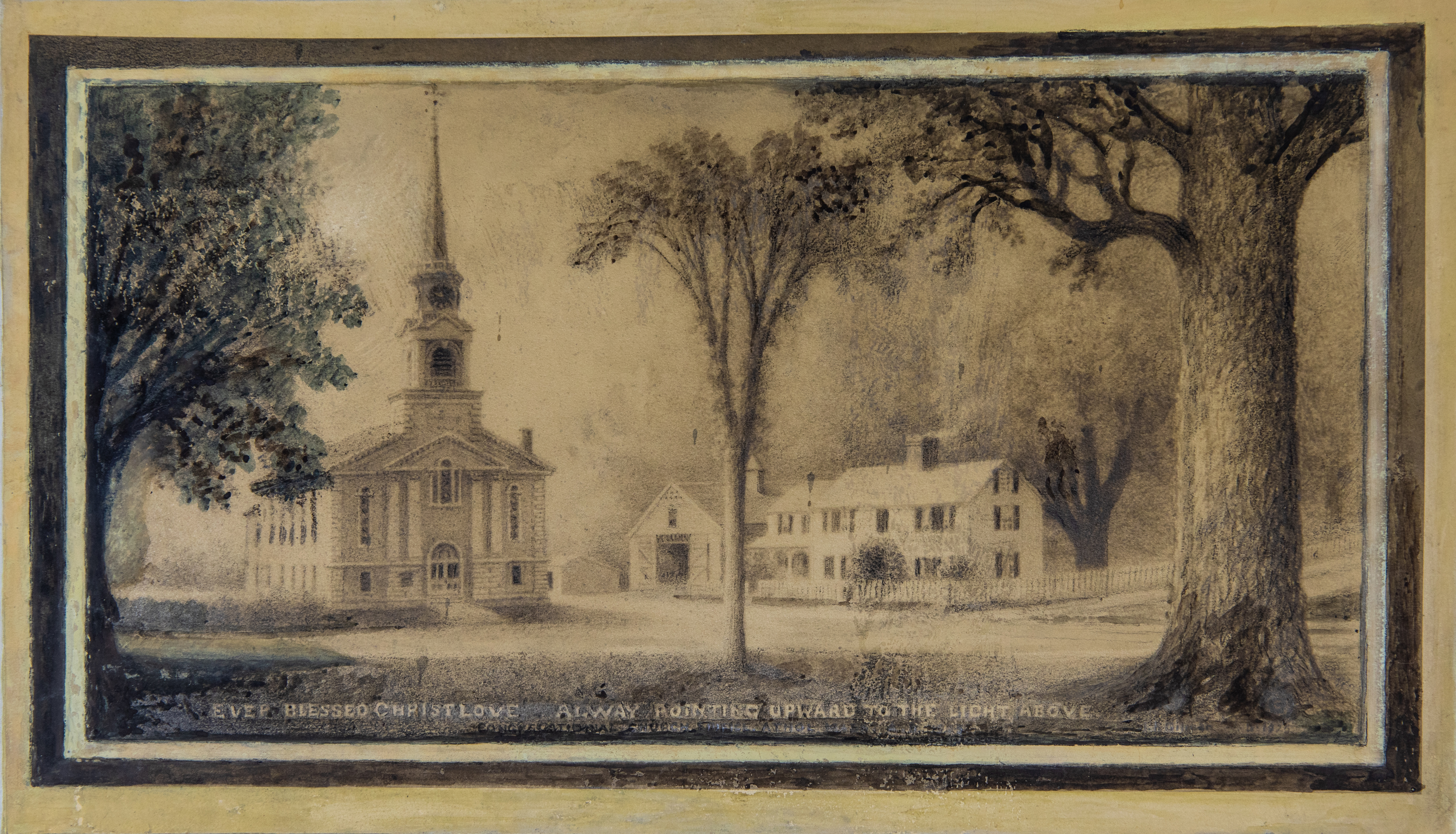

About a month later, August 5, 1920 he came again to Boston, bringing a large picture in sepia of the Baker homestead where Mrs. Eddy was born. It hangs in the Mary Baker Eddy Museum. Another picture of the same subject, but in color, now hangs in the Christian Science Reading Room at Randolph, Vermont. Mrs. Longyear wrote in her dairy that Mr. Gilman was looking very fit and that he told her he was over seventy and worked with a farmer and earned money. He allowed Mrs. Longyear to take his picture with her small Kodak. Some years later, January 5, 1925 he was a guest at the Longyear table at the Twenty-fifth Commemorative Dinner of the Authors’ Club of Boston.

Over the years he made many paintings in and around Athol, often recording incidents in the life of the town. Many of these paintings were reproduced on postcards some years ago and a complete set is now in possession of Mr. Richard J. Chaisson of Athol, a student of the life of Gilman. In 1925 Gilman made his beautiful painting of the Congregational church edifice in the upper town of Athol. It expresses what one critic applied to Gilman’s work, “an affectionate tenderness for his subject.” Many think this was his last work but other paintings may come to light as Mrs. Adele Dawson of Marshfield, Vermont, continues her definitive biography of James Franklin Gilman, which she hopes to publish in 1973. Mrs. Dawson was a member of the active committee which arranged the exhibition of Gilman’s Vermont paintings at the Robert Hull Fleming Museum of the University of Vermont, August 8 to September 4, 1970. The one-day exhibition of Gilman’s paintings of the Athol and New Salem areas followed on September 12, 1970.

Much has been said of Mr. Gilman’s poverty in his late years, but the record of his activities shows him to have lived a free, happy, independent life for many years, frugal perhaps, but hardly recognized by him as poverty with his rich artistic sense of being, and his freedom always to seek a congenial mental milieu. And he had friends, many in his church.

His granite headstone bears the simple inscription:

JAMES F. GILMAN

Artist

1850-1929

The awakening enthusiasm for the painting of James Gilman points to the dawn of a secure place for him among the rural painters of this country.