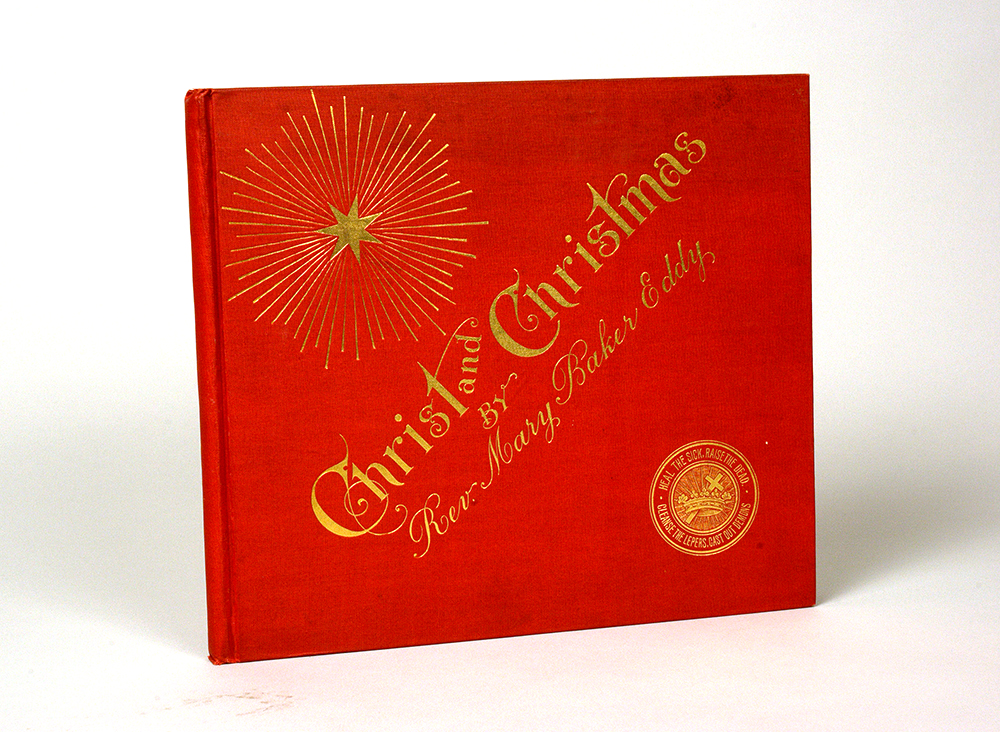

Early in 1893, Mary Baker Eddy, Discoverer of Christian Science and Founder of its Church, completed a poem entitled “Christ and Christmas.” She decided to have it published as an illustrated gift-book, a popular form of the day. It was issued in December of that same year to a flurry of mixed reactions. This article probes the story behind the book and what ensued upon its release to the public a century ago.

To put the Christmas theme of the poem into a historical perspective, it is interesting to note that America was in a period of transition regarding the once sacred Christmas season. One noted writer and historian puts it, “By the era of the Civil War the old festival…was on its way to becoming a spectacular nationwide Festival of Consumption.”1 Major retail department store R. H. Macy’s set sales records in 1867 when it remained open until midnight on Christmas Eve for the first time, and in 1874 it offered its first promotional window displays on a Christmas theme. Although still relatively undeveloped commercially then and into the 1880’s, in 1891 the Christmas season was referred to by retailer F.W. Woolworth as “…our harvest time.”2 On Christmas Eve 1893, an article in the Boston Herald quoted social reformer Elizabeth Cady Stanton regarding the evolution of the observance of Christmas: “I do not think the change is for the better. No one recognizes improvement more than I do, and bearing this in mind I must confess that the celebration of Christmas, like that of marriages and funerals, has been run into the ground.”3 As an example of how far the commercial and gift-giving aspect of Christmas had gone, the Boston Herald ran an article on “‘Misfit’ Christmas Gifts” in their New Year’s Eve 1893 issue.4

For Mary Baker Eddy, the importance of Christmas lay in its spiritual significance.5 In her short article “A Word to the Wise” in The Christian Science Journal of December 1893, she wrote:

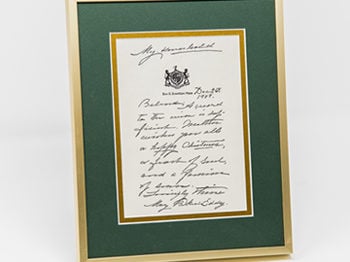

“Will all the dear Christian Scientists accept my tender greetings for the forthcoming holidays and grant me this request, — let the present season pass without one gift to me?

Our church edifice must be built in 1894. Take thither thy saintly offerings and lay them in the outstretched hand of God. The object to be won affords ample opportunity for the grandest achievement to which Christian Scientists can direct attention, and feel themselves alone among the stars.”6

The “Christ and Christmas” poem was completed early in 1893, during a period of significant change and accomplishment in Mrs. Eddy’s experience. She had moved to her home at Pleasant View in Concord, New Hampshire, only months before (in June of 1892). Also in 1892, preparations had begun for the building of her church, the original edifice of The Mother Church; and in September of that same year she had formally reorganized the Church of Christ, Scientist.7

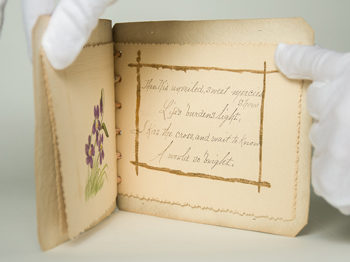

Mrs. Eddy was already the author of numerous books, her major work being Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, the textbook of Christian Science that by 1891 was into its landmark fiftieth edition (a major revision). She was also an accomplished poet from an early age,8 and had been published many times in periodicals and literary compilations of the day.

Just a few years prior to the publishing of Christ and Christmas, there had even been urging by some students who evidently felt strongly that the textbook was difficult to understand, that Mrs. Eddy should “…abandon prose and rewrite Science and Health in verse….”9 This apparently was fueled by an unusual interest at this time by Christian Scientists in popular literature of the day, and anything relating to the life and times of Jesus.10

It is not surprising then that there was also considerable fascination in artistic renderings of Jesus. As one writer expressed his opinion of the scene, “It was felt by nearly every practitioner and student that he must have a picture of Jesus in his house or room, and the question often arose, as to what face of all that were to be had was the most like his.”11 The stage was certainly set for a curious and confused reception to Mrs. Eddy’s illustrated poem (described later in this article), which would attempt to depict her spiritual perceptions of Jesus, the message of Christian Science, and the Christ.

Illustrating the Poem

Mrs. Eddy chose an itinerant artist by the name of James Franklin Gilman, whom she met in 1892, to produce the illustrations with her.12 Prior to this time he had made his living going from farm to farm and producing drawings, etchings, or paintings of those locations and inhabitants. He had become interested in Christian Science in 1884 and had since become a serious student.13 The year 1892 found him in Concord, New Hampshire, preparing sketches of Mrs. Eddy’s home at Pleasant View for her photographer, Mr. S. A. Bowers.14 After having been shown the sketches, Mrs. Eddy invited both Mr. Bowers and Mr. Gilman to visit her on the evening of New Year’s day, 1893. A friendship and correspondence was begun, Mrs. Eddy expressing loving interest in Gilman’s spiritual progress.15

On March 11, 1893, Mrs. Eddy invited Mr. Gilman to Pleasant View, this time to request that he work with her on illustrating the poem she had recently completed, “Christ and Christmas. “16 She gave him the text of the poem to ponder, allowing him the freedom to “look to God for guidance and inspiration.”17 Shortly thereafter, also in order to prepare Gilman for what she had in mind, she showed him the illustrated poem O Little Town of Bethlehem by Phillips Brooks, and later on The New World by Carol Norton.18

Over a period of months, the making of illustrations for such a poem became far more of a humbling spiritual journey than Gilman had realized when he accepted the task of translating Mrs. Eddy’s refined spiritual expressions into a visual medium. He found himself being challenged and instructed, gaining in understanding, and willing to turn wholeheartedly to God and away from his own sense of self when the work did not go easily, and when the project seemed unable to go forward.

Mrs. Eddy had wisely requested that he keep to himself what he was working on, and not even share or discuss it with the faithful workers in her own household. Gilman came to understand that he was not to allow any other influences on himself. He even goes on to say that “she [Mrs. Eddy] saw then what she later definitely expressed in saying she found my mentality uncommonly plastic and impressible.”19

In his reminiscences of his work with Mary Baker Eddy, Gilman mentions many struggles along the way, but one particular instance, indicative of his inherent and continuing difficulty of relating to Mrs. Eddy’s higher view, was with the illustration that she had in mind of “two angels moving swiftly through the air to welcome the approaching dawn.” Her idea of angels as not having the conventional “feathered wings” left him bewildered as to how they would be recognized as angels.20 To help him understand this concept and to be able to translate that idea into a visual representation, she showed him a picture she had with two angels which she liked (with the exception of the wings). It gave him the idea that he needed, and inspired him “…[to make] the rest of the picture suit the high requirements of Mrs. Eddy’s thought.”21 It is interesting that this incident took place in June 1893, and in the August 1893 issue of The Christian Science Journal there was an article by Gilman entitled “Angels” that chronicles his understanding of the term as Mrs. Eddy uses it, in the more spiritual sense. That article contains a reference to “angels” from a letter Mrs. Eddy had written to a student, the basic wording of which appeared later in her Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896.22

Making of the Book

By mid-July most of the illustrations were ready, and the publishing process commenced. Mrs. Eddy had hoped to have the book completed in time for the Parliament of Religions to be held in conjunction with the World’s Fair (Columbian Exposition) in Chicago that September, as plans were already underway for a presentation on Christian Science. Although Gilman was overseeing the project himself in painstaking detail, the attempt by a local [Concord] publisher to reproduce the illustrations was a failure, mainly because of strong feelings against Mrs. Eddy by the chief plate-maker.23

Perceiving what must be done to insure the unhampered progress of the project, Mrs. Eddy arranged for Gilman to go to Gardner, Massachusetts, to work with a publisher there. She instructed him not to reveal for whom the work was being done, having seen from the previous experience what problems the mention of her name seemed to incur. A communications system and an efficient and secure method of transport for the pictures were devised, and Mr. Gilman departed for Gardner on Monday, August 28.

He returned to Concord a week and a half later on Thursday, September 7, with proofs from the plates in hand. This time the reproduction work had been successful, and all that remained now was the printing. Mrs. Eddy received the first copy on November 28.24

The finished book contained a title page naming Reverend Mary Baker Eddy as author, a copyright page, the poem interspersed with eleven illustrations, and before the “finis” page, one that read “Rev. M.B.G. Eddy, and Mr. J.F. Gilman, Artists. Mr. H. E. Carlton, Photograveur.”25 When shown the credit to his name Gilman recalls, “This was unexpected to me…,” as Mrs. Eddy had seen the wisdom in his not having his name or initials on any of the illustrations, and he felt this printed tribute “…far more than compensated….”26

The Book’s Reception

The atmosphere into which the book emerged was charged with conflicting opinions about Mrs. Eddy and Christian Science. On the one hand, the Christian Science movement was growing at an incredible rate, from 45 churches in 1889, to 242 in 1894.27 However, this presented daily challenges for Mrs. Eddy to maintain correct teaching and preaching within its ranks. There had been considerable upheavals, and the church had just recently been reorganized in 1892. There was reason to hope that the release of the book would help correct conditions of thought existing in the Christian Science movement at the time, and in one observer’s opinion, possibly to clear the way for the building of the original Mother Church edifice.28

In addition, although immediate evidence indicated that Christian Science had made quite a successful presentation at the World’s Parliament of Religions held in Chicago earlier in 1893, the event had tended to crystallize opposition against Christian Science and Mrs. Eddy by the more traditional Protestant and Catholic churches, who saw it as more akin to the Eastern religions than to Christianity.29

All of the above conditions were further confused by the difficulty of many of her followers and former students to truly understand Mary Baker Eddy and her unique position as an increasingly prominent female religious leader. There was the definite and widespread tendency to dwell on her personality, a problem she spent countless hours attempting to correct by repeatedly turning them to her spiritual message, as contained in her writings.

It is no wonder, then, that the illustrations drew far more comment than the poem itself. While there were praises given for the high quality of the artwork, there was on the other hand outrage and criticism that the illustrations had no artistic merit.30 In a December 14, 1893 letter to her student, Carol Norton, Mrs. Eddy wrote, “The Christ and Christmas was an inspiration from beginning to end. The power of God and the wisdom of God was even more manifest in it and guided me more palpably…than when I wrote Science and Health…. [God] taught me that the art of C.S. has come through inspiration the same as its Science has. Hence the great error of human opinions passing judgment on it.”31

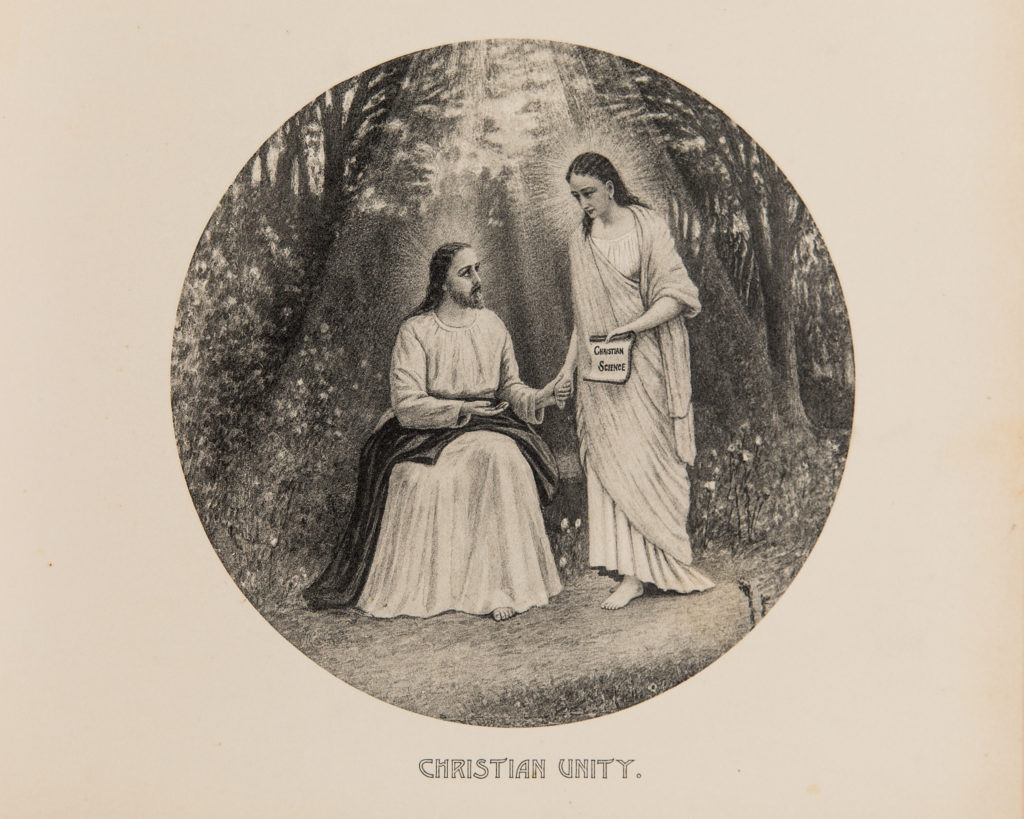

In addition, there was a reaction by friend and foe alike to endeavor to interpret in the artwork a personally-based metaphysical symbolism. The controversy brewed especially over the illustration “Christian Unity,” which depicts a seated Jesus-like figure with halo, holding the hand of a standing female figure (also with halo). This female figure is holding a scroll inscribed with the words “Christian Science.” The correlating passage of the poem reads:

“Winged Christian Science soars to view

The great I Am,

With all His glory shining through

Mind, mother, man.

As in blest Palestina’s hour,

So in our age,

‘Tis the same hand unfolds His power,

And writes the page.”

The female figure was said to resemble Mary Baker Eddy in this as well as in some other illustrations. This particular illustration was an especial affront to the more orthodox Protestant and Catholic clergy of the day, who saw it as blasphemous.32 Interestingly, however, it was the absence of human origin that she seems to be expounding in the verse.33 Mrs. Eddy commented in a Journal article, “The clergymen may not understand that the illustrations in ‘Christ and Christmas’ refer not to my personality, but rather foretell the typical appearing of the womanhood, as well as the manhood of God, our divine Father and Mother.”34

Soon after the book was released, reports began to reach Mrs. Eddy of its wonderful healing effect, especially by close study of the illustrations.35 Of course, healing was always desirable, but to Mrs. Eddy this “picture-healing”36 was not in accord with the primitive Truth that Jesus had taught, or the method she had discovered, proven, and made practical to this age. Gilman recalls her commenting that this sort of healing was “through…blind faith and worship and not through understanding, which will not do; that is not the Christian Science idea; that is one reason why I must withdraw it.”37

Also disturbing to Mrs. Eddy was hearing from a close student of his memorization and use of the poem for treatment, a practice she immediately discerned as the use of a “mental opiate.”38 And so, in January 1894, just weeks after its introduction and already into its second edition, she was compelled by its general misuse to withdraw the book from publication.

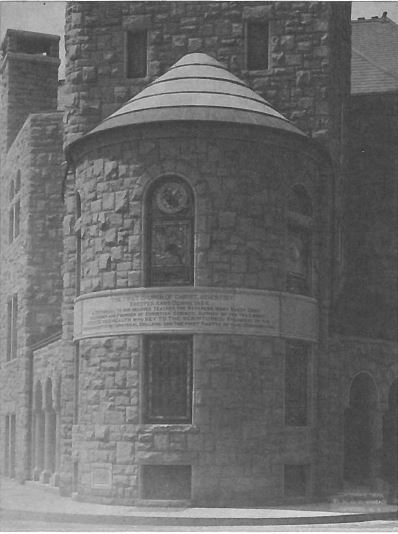

It is important to note though, that even after its withdrawal, three of the illustrations from the book were used as the basis for design of the stained glass windows in the room set aside for Mrs. Eddy in the original edifice of The Mother Church, completed in late 1894. Those three were “Star of Bethlehem,” “Suffer Little Children to Come unto Me,” and “Seeking and Finding” (without the serpent).39

Withdrawal and Subsequent Re-release of the Book

In The Christian Science Journal of February 1894 Mary Baker Eddy wrote of Christ and Christmas, “The poem and illustrations are not a textbook. Scientists take them too hard. Let them return to the Bible and ‘Science and Health’ which contain all, and much more, than they have yet learned. We should prohibit ourselves the childish pleasure of studying Truth through the senses, for this is not the intent of my works.”40 Earlier in that same article, Mrs. Eddy as Teacher and Leader humbly shares a further insight into the book’s purpose, “The little messenger has done its work, fulfilled its mission, retired with honor, and mayhap taught me more than it has others. This knowledge I have gleaned from its fruitage, namely, that contemplating finite personality impedes spiritual growth, even as holding in mind the consciousness of disease prevents the recovery of the sick.”41

The afore-quoted article was published later in Mrs. Eddy’s Miscellaneous Writings, under the title, “Deification of Personality.” The revised article refers to the “…little messenger [as having] done its work…retired with honor…” but adds “…only to reappear in due season.”42

In December of 1897 the book did reappear, in its third edition, and was described in The Christian Science Journal issue of that same month as “A revised edition with improved plate of the illustration, ‘Christian Science Healing.'” Among other details, the improvements included a different expression on the face of the woman attending (healing) the patient, her eyes and face turned upward, and her cape having been changed to white (from the previous black one). Not mentioned in the Journal advertisement but also in the third edition were significant textual changes; and a few copies were printed with a cropping and altering of the illustration “Seeking and Finding,” resulting in the omission of the serpent behind the woman.43

By the fourth edition (1898), there were extensive changes in the illustrations “Truth Versus Error” and “The Way.” In “Truth Versus Error,” the floor, doormat, and door were changed; the word “Truth” on the scroll and “Mortal Mind” on the doorplate were dropped; and there appeared beneath the picture, “Behold, I stand at the door and knock.” In the fifth edition (1900), this line was dropped. In “The Way” illustration, previous to the fourth edition there had been only one cross, with a Jesus figure and a dove above in a cloud of suggested childlike faces. In the fourth edition and on, Jesus, the dove, and the host of faces have been removed. There are now two crosses and a crown, rising in succession.44 During the making of these changes, Mrs. Eddy wrote Gilman, “The art of Science is but a higher spiritual suggestion that is not fully delineated nor expressed, but leaves the artist’s thought and the thoughts of those that look on it more rarified.”45

There were nine editions of the book in all. Subsequent to the major revisions in the second, third, and fourth editions, there were only minor changes in detail, especially in typeface and borderwork, and of course in the title page, which reflected edition numbers, dates, printers, and locations of Mrs. Eddy’s official residence.