This two-part memoir of Mary Beecher Longyear was written by her youngest son and was originally published in the Museum’s Quarterly News in the autumn of 1971. The first part covers her early experience until her move to Boston.

DURING THE DECADE from 1840 to 1850, emigrants from New York State, Pennsylvania and Ohio poured into Wisconsin. In this stream, in 1844, a young man named Bryant, a cousin of the poet, William Cullen Bryant, and his partner, Samuel Peck Beecher, left Buffalo to set up a nursery business in Milwaukee. With Beecher came his 15-year-old bride, Caroline Matilda Walker, who learned the duties of a housewife between the births of five children by the time she was 21. Her fourth and fifth children were twin girls named Abby and Mary Hawley. The latter is the subject of this memoir.

After dissolving the partnership, Beecher with his family, now increased to seven children, moved to Erie, Pennsylvania, where he established himself in the same business. The twins were inseparable. They were dressed alike, but there was never any difficulty differentiating them. Mary was blue-eyed and blonde, Abby, brown-eyed with glorious chestnut hair. They started school together timidly; they sat where they were told to “for the present” and together burst into tears when they learned there wasn’t any present forthcoming!

At the close of the Civil War, Beecher decided to move again. This time, his choice fell on a farm in Augusta township, about five miles west of Battle Creek, Michigan. Here, conditions were much more primitive than in Erie. Beecher lost no opportunity of urging useful skills upon his children. His exhortations bore fruit with the twins, who both chose school teaching. At 16, they entered Albion College together to study for teacher’s certificates.

The religious training of the young Beechers appears to have been carried out mainly in the home and to have emphasized Bible readings. During the early years in Erie, there are references to Captain Wilkins’ Sunday School, but after the family moved to Michigan, the opportunities for church attendance were rare. Both parents, whose New England forebears for seven or eight generations were habitual Congregationalists, accepted that denomination, but had apparently little interest in church organization or activities.

Mary Beecher’s first school assignment was at Marengo, five miles west of Albion, where she had to be janitor, teacher, and principal at the one-room wooden schoolhouse. After a year at Marengo, Mary had saved enough to take a term of instruction at the State Normal School at Ypsilanti. Some seven years after starting to teach, Mary Beecher borrowed money from her father to take a further year’s course at Ypsilanti for an advanced certificate which would entitle her to a better salary. Armed with this, she had every right to regard herself as a professional.

Abby had been teaching at Benton Harbor, and caused Mary’s interesting but predictable world to collapse by announcing her engagement to Edward Abbott, a druggist’s clerk from the state of Maine. She was married soon after, and went South with her husband who had saved enough for him to purchase a half interest in a china-ware store.

Mary, deprived of the usual consultation with her twin about a school post for the next year, went to Calumet to teach. However, an acquaintance pictured the advantages of Marquette over Calumet so persuasively that Miss Beecher seized an opportunity of filling a vacancy there. She attended the Marquette Congregational church and applied for membership.

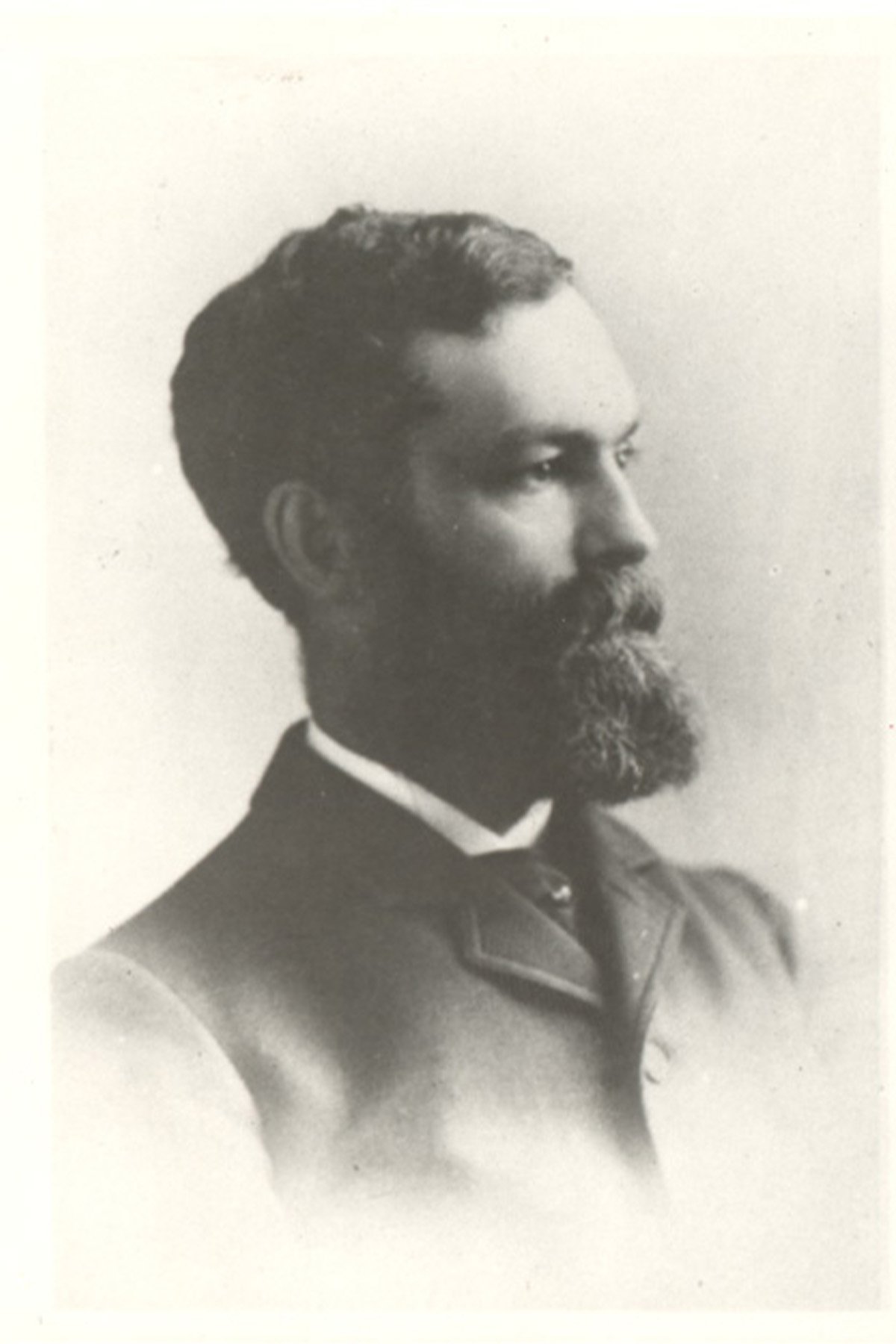

One Sunday, she noticed in the pew in front of her a tall man with curly black hair and a fine full black beard. She learned that his name was John Munro Longyear and that he was the eldest son of a recently deceased Federal Judge in Detroit. He was working as “landlooker,” reporting on the natural resources of lands ceded by the Federal Government to the Sault Ste. Marie Canal Company. Miss Beecher saw to it that she obtained an introduction to the attractive stranger.

John Munro Longyear and Mary Hawley Beecher were married at the bride’s parental home at Augusta the January following their engagement. The bride never spoke of a honeymoon, and it is probable that her husband’s new responsibilities as resident agent for Eastern interests with local holdings required their immediate return to Marquette.

After a few years, her husband was doing well. His detailed knowledge of large areas of undeveloped land in the Upper Peninsula, gained in his “landlooking” days, was beginning to bear fruit, not only for the owners, but also for himself. During this period three children were born to the Longyears—a daughter and then two sons.

However, their bright material prospects were suddenly overshadowed; little John Beecher, the youngest child, became ill. A doctor was called who prescribed the usual medicaments and the child appeared to be recovering; however, he suddenly became acutely ill and died before the doctor who had been summoned could arrive. The shock to the mother was profound; she, who for 30 years had met the contrarieties of life by opposing them, now found all human effort vain. The formal comforts of her church worthless, her confidence in the science of medicine and its practitioners shattered, where could she turn for assurance in the future for her two remaining children, her husband and herself? She turned to prayer, after raging at fate, and found her only moments free of fear when she truly entered her closet alone and asked guidance of God.

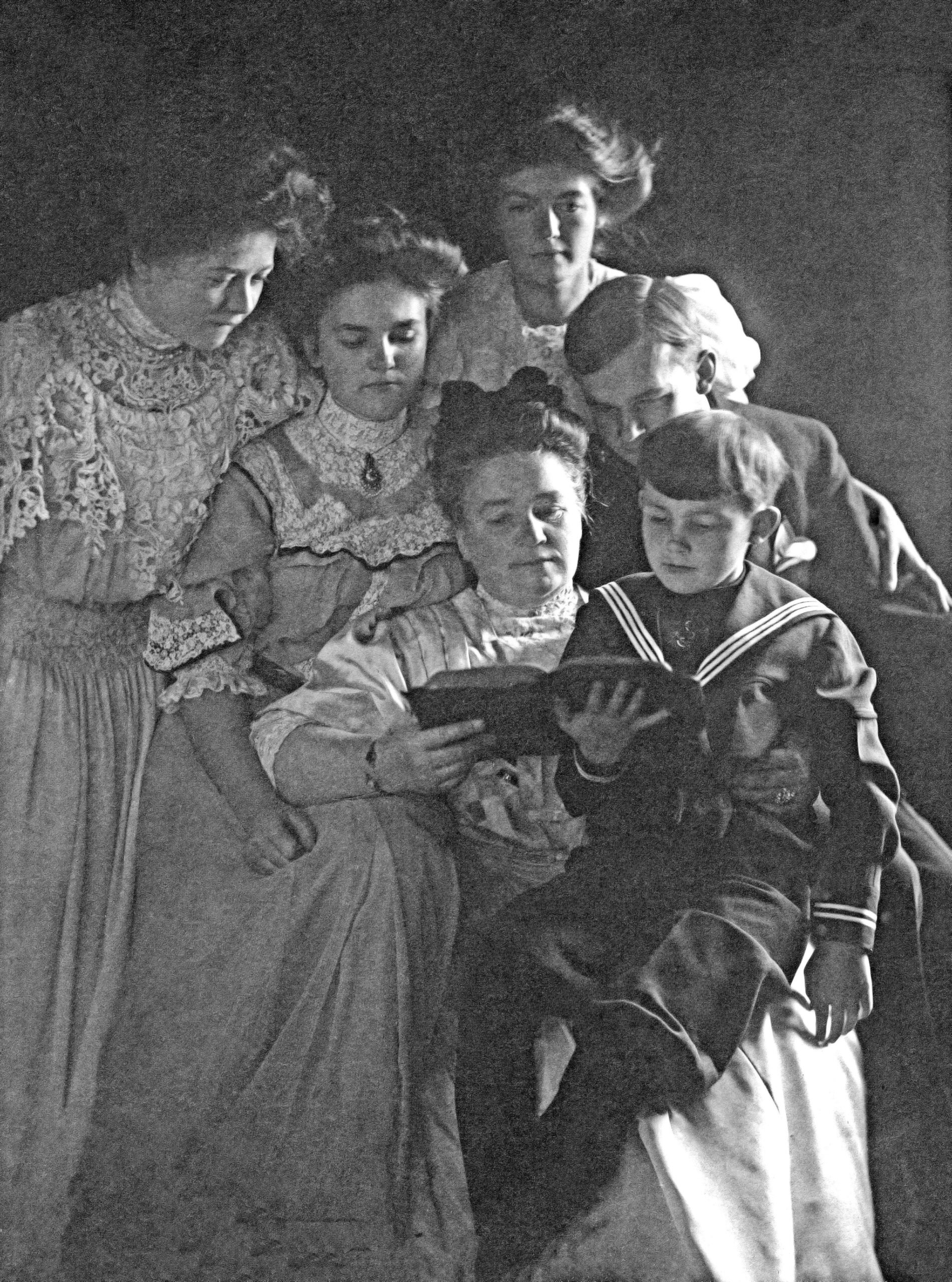

Through all the well-meaning efforts of family and friends to divert her thoughts, Mary continued to pray for guidance toward security and sought practical means to rebuild her assurance. Distrustful of drug-laden medicines, she was attracted to the doctrine of homeopathy, but could find no one in Marquette capable of explaining its practice. During these troubled years, two more children, both girls, were born.

Her search revealed the existence of methods of mental healing, beginning to make themselves known beyond their places of origin. Among these, Christian Science appeared to the harassed mother as opening a way in the direction she wished to go. She was then on a short visit to Chicago and under obligation to return to Marquette. Before she could go further into the matter, on her way home, she bought at a bookstore a copy of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy.

A first reading of the textbook convinced her that her long search was ended and that here she had found the key to the puzzle with which life’s uncertainties had confronted her. She felt that her prayer of desperation to a God she had always regarded as a loving Father was truly answered; she had been shown what to do, and now it was up to her to do it.

Another son was born, 3 1/2 years after the latest daughter, and early showed signs of great susceptibility to changes of temperature. Born in mid-October, his chances of surviving a Lake Superior winter seemed slim; in her yet confused state of thought, his mother decided to take all her family to California for the winter. Alerted to the danger of unauthorized practitioners, she sought out Miss Sue Ella Bradshaw, an authorized Christian Science practitioner in San Francisco. Miss Bradshaw cleared away the confusions in Mrs. Longyear’s thought and imparted renewed confidence in the effectiveness of the Science of Christianity. While the family was in San Francisco, the baby became ill and the mother called on Miss Bradshaw for help. The old fear of nearly six years before assailed her spirit once more, and she pleaded with Miss Bradshaw to come and sit with the child; she, the mother, would not leave his side. The practitioner, recognizing the human fear, said, “You must learn to leave him with God; God is ever-present, and your confidence that God is beside him and beside you wherever you are will destroy the false claim.” Overcoming her fears, Mrs. Longyear dined with the family in the hotel. Returning to their rooms, she asked the child’s nurse:

“How is the baby?”

“Oh, Ma’am,” she beamed, “he hasn’t coughed once since you went down. He woke up hungry, so I gave him a banana.” (A banana for an infant of a few months was regarded in those days as highly indigestible!) No further difficulty was experienced by the baby and from that time on, Mrs. Longyear placed her whole reliance on Christian Science as the method for solving difficulties and as a way of life.

Her temperament never having been one to settle into habitual routine, Mrs. Longyear sought to broaden her experience beyond the confines of the community of which her husband had become the mayor. As his term of office was ending, a large stone house designed to care amply for his numerous family was nearing completion, and his wife was faced with the problem of furnishing and staffing it.

It had been her duty to entertain numbers of highly placed members of the financial world when they came on trips of inspection to that frontier country. One younger son of an English peer had stayed some time in the region, finding sympathetic hospitality at the Longyear home. He missed his own home and gladly shared the activities of his host’s young family and showed great interest in the new brownstone house under construction. When he departed, he left pressing invitations to his host and hostess to come to England where his parents would be delighted to make them as welcome as he had been made in Marquette.

When Mr. Longyear’s term as mayor ended, he and his wife embarked on their first trip to Europe. Arriving in England, they were warmly welcomed by their former guest, and by his parents. It must be admitted that Mrs. Longyear rather startled her hostess with a request that she might be instructed in the details of operating a large establishment; but the evident sincerity of her inquiry was appreciated. The American guest accordingly spent several most instructive hours with the housekeeper and the butler. She repeated her request at other homes, and returned to Marquette with copious notes. These formed the basis of her serious efforts to perfect the method of training and maintaining a large household staff. Her efforts finally resulted in the publication of her book, The Law of a Household, under the pseudonym of Eunice Beecher.

Mr. Longyear was glad indeed, to find that his wife’s moods of despair and depression had ceased, and had no hesitation in giving Christian Science the credit. He had, however, little interest in applying its practice to himself until a recurrent muscular rheumatism attacked him after a period of relative freedom from pain. His wife asked him whether he wished to have treatment, and he agreed. She applied what she knew of Science, and in a short time, the pain ceased. He thanked her, but from previous attacks he had had similar relief. It was only after a year or more that he realized that he had had no return of the pain, when he forthrightly admitted to his wife that he henceforth accepted the teaching of Christian Science without reserve.

A decrease in income made it advisable to close the Marquette house after little more than two years’ occupancy and transport the family to a Paris pension where expenses could be kept down. The children would benefit by the experience of living in another country, acquiring another language, and would broaden their outlook.

Mrs. Longyear enrolled as an art student and found her lessons fascinating. She acquired a practical approach to painting which gave her immense pleasure and provided her with a hobby which she loved and gladly shared with others. Although she never achieved good drawing, her native and accurate sense of color received a training and discipline which attracted artists. Many years later, when John Singer Sargent and Bernhard Berenson visited her in Brookline to see a Moroni portrait, Berenson’s quick eye passed over several other paintings. In the hall, Mrs. Longyear had hung inconspicuously one of her oils. On his way out, Berenson stopped short, pointed to the picture and said, “Now, who did that? It has real life!” Mrs. Longyear admitted her work, and Berenson’s notice was one of her most treasured memories.

Two years abroad, the first in Paris, the second in Dresden, were filled with activity, primarily concerned with painting in Paris and with music in Dresden.

With all these occupations, her attachment to Christian Science remained paramount. She interested several people at the pension, and found responsive thought among French Protestants. True to her impulses, Mrs. Longyear wrote her first letter to Mrs. Eddy to suggest a French translation of Science and Health.

A number of people came to Dresden to ask Mrs. Longyear about Christian Science, and a group gathered on Sundays to read the Bible Lessons. Several notable healings took place, and the impulsive matron wrote to Boston to report the eager interest she had found. This interest was not confined to Dresden, for Herr Eckert had been active in Stuttgart and Frau Günther-Petersen in Hannover, starting Christian Science services in both of these cities. Upon her return to the United States, Mrs. Longyear arranged for Mrs. Frances Thurber Seal, a pupil of Mrs. Laura Lathrop, to be sent to Dresden to carry on the work in Christian Science. Mrs. Longyear supported this work financially for several years. Mrs. Seal became a Christian Science teacher herself and returning to Germany made Berlin her headquarters for teaching and healing.

When Mrs. Longyear returned to Marquette after two years of intellectual and artistic stimulus abroad, she could not help feeling that her children merited wider opportunities than were available at home.

Boston proved congenial with its literary and artistic resources. That it also harbored the headquarters of the Christian Science movement was at first almost incidental. She used the children’s term time to make herself more familiar with the writings of Mrs. Eddy, and by her study to seek indefatigably the occasions in daily life to apply the teachings of Christian Science. Of the three daughters, two eventually made professional appearances as singers and the other earned an architectural degree at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

For three years, the family divided its sojourns between Boston and Marquette. Howard, the eldest son, did well at Lawrenceville and entered the forestry school at Cornell University.

The year 1900 put to severe test the progress that this devoted mother thought she had made in the study of Christian Science. The beloved and cherished Howard, on vacation from his first year in Cornell, started with a friend on a canoe trip towards the Club near Huron Mountain. A sudden thunderstorm overtook them as they were crossing a wide bay, and both young men were lost. Even in the midst of her maternal grief, the mother held fast to the assurance that accidents are not God’s doing; the equally bereaved father contributed a staunch steadfastness in the face of the apparent destruction of his long-cherished plans for his eldest son.

Whether or not she realized it at the time, the mother in later years admitted to having trusted too far the power of humanly parental brooding love, and the building of material hopes about the person of this talented son. The lesson she learned from this seeming disaster was to lift her personal thought above the trials of parenthood and to see her children as God’s reflections rather than her own offspring. It was a hard lesson, not always understood either by herself or by her children, but it gave her thoughts a wider scope and an awareness of the world’s needs which over the later years inspired her work for the Cause of Christian Science and culminated in the establishment of the Zion Research and Longyear Foundations.

An ore-carrying railroad which had constructed ore-docks four miles north of Marquette wished to extend its tracks along the shore into the city. This meant circling the Longyear property and the adjacent residential district on three sides.

This so disheartened Mrs. Longyear that her husband suggested a summer cruise with the children to Northern Europe, in the hope that a radical change of scene would help her in overcoming her disappointment. He accompanied them, and from this trip, which included a visit to the desolate island of Spitsbergen, originated his development of the coal deposits there.

Mr. Longyear returned to Marquette for a last effort to dissuade the railroad from circling his home, while the rest of the family went to Paris again for the winter. The point of no return was reached when news came that the railroad “was blasting below the house.”

Mr. Longyear arrived in Paris to bring his family back to the United States. One pleasant spring Sunday, while they were driving in an open carriage in the Bois de Boulogne, along with hundreds of others, Mr. Longyear murmured in his deep voice :

“You know, Molly, I think I could move the house and rebuild it in Boston.”

His wife flung her arms about him and cried:

“Oh, Mun, I know you can, I know you can!”

His cautious nature began to marshal reasons for not doing what he had proposed, but her enthusiasm for the idea, and evident feeling that in the proposal lay a foundation for a bridge of continuity between past and future persuaded him to carry the idea of the moment to fulfillment.

First in a two-part series. To read the second installment, click here.