This two-part memoir of Mary Beecher Longyear was written by her youngest son and was originally published in the Museum’s Quarterly News in the autumn of 1971 and the winter of 1971-72. This second part covers her experience after her move to Boston.

MARY BEECHER LONGYEAR, after returning from Paris in the spring of 19021 to settle in Boston permanently, found purpose as a local member of The Mother Church. She renewed her acquaintance with members and administrators she had previously met, and was able to take part in the manifold activities of the movement.

In June 1905, Mrs. Eddy invited Mrs. Longyear to Pleasant View where the two ladies had an hour’s conversation. After Mrs. Eddy left for her drive, Mrs. Longyear visited with Mrs. Laura Sargent with whom a continuing friendship was begun. Of the conversation with Mrs. Eddy, her guest never spoke in detail. She did report that when she left Mrs. Eddy’s study Mrs. Sargent inquired, “What in the world were you talking about that made Mother laugh so heartily? I haven’t heard her laugh like that since I don’t know when!”

Mrs. Eddy enjoyed her few personal visits with Mrs. Longyear because the latter never came to her with a problem to be solved or a favor to be granted. Both had lived in the country as girls, and their common background afforded a platform on which a link of mutual human understanding could be forged.

She also brought up in a letter to Mrs. Eddy a proposal that places of refuge be established which might be termed “Sanatoria,” where persons wishing Christian Science treatment could find a place of quiet sojourn and be visited by their practitioners in an atmosphere free of the turmoil of mortal thought. The proposal interested Mrs. Eddy, but action was postponed until 1919, when the Christian Science Board of Directors established the Benevolent Association home at Chestnut Hill. (At that time Mrs. Longyear donated the land on Single Tree Hill, Brookline, where it is now located.)

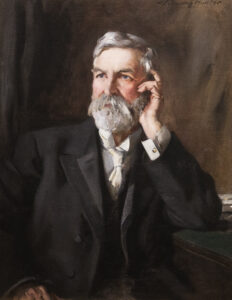

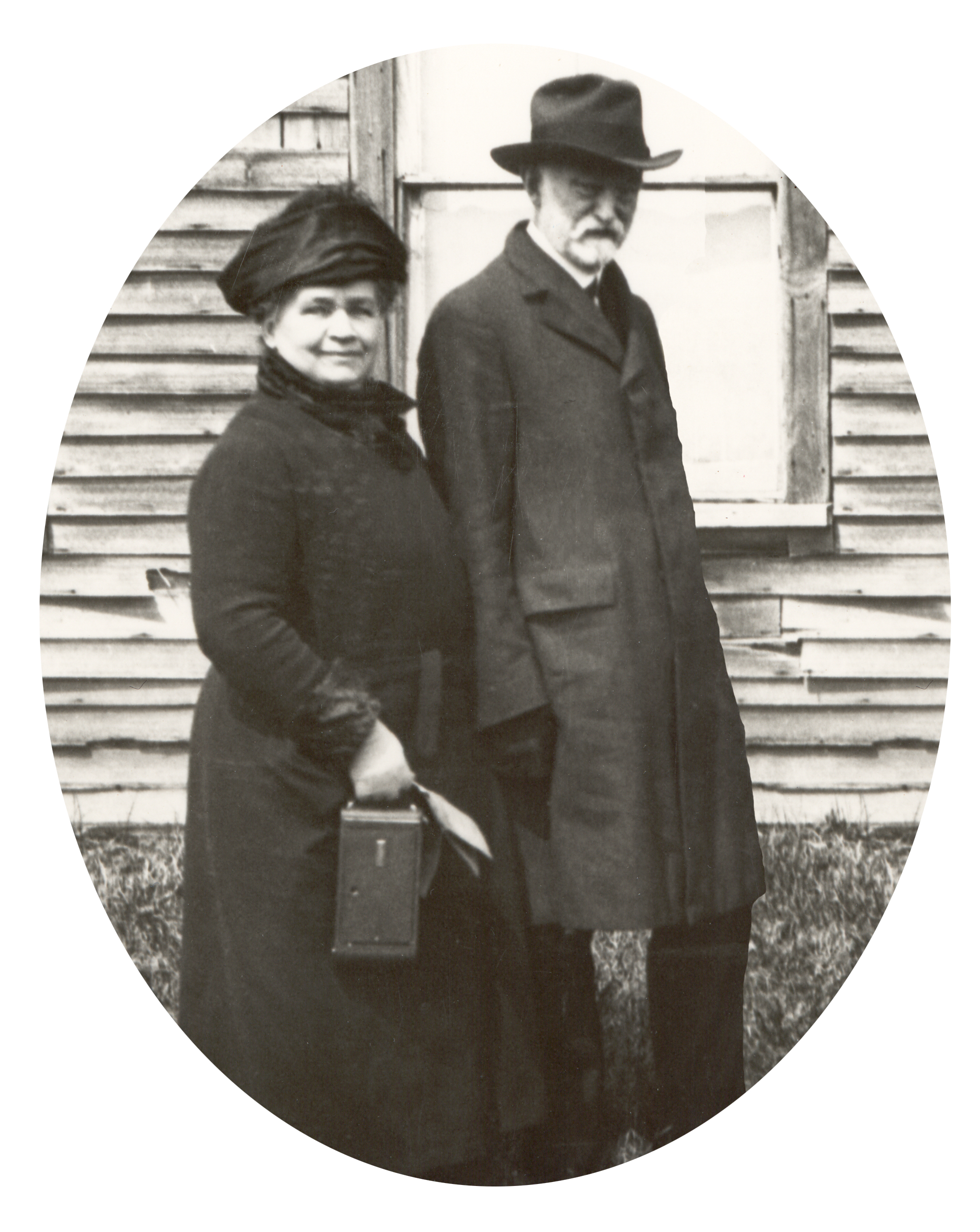

During the first decade of the twentieth century, those who knew her and worked with her deeply respected Mrs. Longyear’s direct and frank manner, her candid and unaffected reliance upon God, and her entire lack of personal pride. She had clear, intensely blue eyes, a straightforward, somewhat didactic manner of speaking—a heritage from school-teaching—and a direct line of cogent argument when she was sure of her ground. Her voice was clear, of a soprano quality, and carried easily when she sang, as she often did about the house.

Liberal in sentiment, seeing her affluence as a means for improving situations brought to her notice, she became interested in many activities, some purely Bostonian and others of international scope. The World Peace Society, whose president was Mr. Elwood Mead, had her support for a number of years. She joined, and persuaded her husband to join, the Twentieth Century Club whose Saturday luncheons she greatly enjoyed, meeting there figures from New England’s cultural flowering, such as Frank Sanborn, Thoreau’s biographer; John Orth, Liszt’s pupil; and the redoubtable Father Van Allen of the (Episcopal) Church of the Advent, with whom she did not hesitate to cross swords when he inveighed against Christian Science. She and Mr. Longyear also became interested in the further development and expanding use of the Braille system for the blind, and substantially endowed J. Robert Atkinson, the founder of the Braille Institute, in this work. She found time to explore the colonial ramifications of her parents’ families and supported the Massachusetts Historical Society. The Museum of Fine Arts benefited by her patronage, and she and her husband had a large share in the establishment of a repertory theatre by Henry Jewett and his company of actors. They were box-holders at the Boston Opera House during its first three seasons. Her interests in so many directions were always with a purpose beyond self. She never sought or accepted a post on a committee or a title of official standing to bring her person into prominence.

Searching for a site on which to reconstruct their home, Mr. and Mrs. Longyear looked at scores of properties in the Boston suburbs. Their task was greatly advanced by Mr. Longyear’s purchase of the family’s first motor car, a White Steamer 1904 model touring car. Gradual elimination of other sites left eight acres at the top of Fisher Hill in Brookline as the best. A puzzle existed as to which of two sites, each a four-acre tract divided by Hyslop Road, was preferable. An old Marquette friend, Miss May Burt, daringly recommended a site for the house in the middle of the road. The Longyears purchased both tracts and had the road between them condemned for public use.

Moving the house from Marquette to Brookline took four years, was commented on in the national press, and brought much unwanted publicity. The general opinion seemed to incline to the idea that the house was re-erected in Brookline exactly as it had stood in Marquette. This is not the case. While many features of the Marquette house were retained, the house on Fisher Hill is much enlarged from its predecessor.

The larger house took a great deal of Mrs. Longyear’s time. The interior decoration of the home caused its mistress constant preoccupation. She visited decorators’ shops by the score in Boston and New York, seeking someone in whose advice and taste she could confide, but without success.

As always, when discouraged she turned to prayer and to her understanding of Christian Science. After a fruitless search of several days in New York, she left the hotel one morning with no idea where to go next. Her eye was caught by a sign across the street: “Alice E. Neale, Decorator.” Without introduction or investigation, she went into the tiny one-room shop and made the acquaintance of its proprietor, whose vast knowledge of style and recognition of true craftsmanship had embellished many mansions about Chicago, but who was just beginning in New York. A strong bond between the two women was established. The following years frequently saw Miss Neale at Brookline. It was her ability to search out fine old furniture to harmonize with her client’s older pieces of value, plus her knowledge of places where fine craftsmanship was still available, which were the principal factors in building up the successful combination of formal decor and homelike comfort that prevailed in the house. When the music room was completed, it was Miss Neale who knew where to find the young Italian who had a Prix-de-Rome award for bas-relief. The ceiling decorations are the result.

Mrs. Longyear was tireless in her experimentation for the smooth operation of her household. The large staff of servants each had a typed loose-leaf book detailing his respective tasks and the days on which they should be done. These were kept up-to-date as new requirements proved necessary. The housekeeper had a master copy to aid in her supervision. So much interest was aroused by her system that she finally had a summary of it published under the title “The Law of the Household.” So the seed planted by her sessions with housekeepers and butlers in England twenty years before bore fruit. On the strength of this publication she was invited to become a member of the Boston Authors’ Club, whose meetings she greatly relished.

The diversity of her activities never deflected her from the daily discipline and earnest study of Christian Science. She served for several years as a teacher in The Mother Church Sunday School where she taught girls between the ages of twelve and sixteen.

A demonstration of the practical application of the teachings of Christian Science was afforded by her then daring experiment of having transplanted mature trees to mitigate the stark bareness of the new house. The hilltop boasted only five starved, drooping elm trees, a few apple trees in a remote corner, and one large elm near what is now the entrance gate. The latter had recently lost one of its two main branches in a storm and seemed to have been mortally wounded. The mature trees were in the line of a nearby road widening project and had to be hurriedly uprooted in full leaf. Teams of six or eight workhorses hauled them with huge root clumps of earth to the positions designated. Portable cranes were needed to set them upright in the holes provided. The operation drew the attention of landscape gardeners, none of whom gave the trees the slightest chance of survival. For a few years their opinions seemed justified; meagre foliage and dry branches mocked Mrs. Longyear’s bold concept. But she never faltered in her efforts to work out the problem along Scientific lines. After five or six years nearly all the trees were thriving. The skinny elms and the wounded one leafed out each year, giving constantly spreading shade, and, with other trees planted later, now provide the well-wooded grounds which visitors to the Foundation can enjoy.

With so many interests to occupy her energies, one may well wonder at what point the thought of a Foundation began. During Mrs. Eddy’s earthly career, Mrs. Longyear had been invited to see her four or five times at widely separated intervals. She occasionally sent Mrs. Eddy small remembrances, such as fruits from her garden, and once she recalled a frontier delicacy, squirrel pie, and had one prepared and sent. Mrs. Longyear did not seek to visit Mrs. Eddy after she moved to Chestnut Hill, but did have frequent visits with Mrs. Sargent.

Mrs. Eddy’s passing in 1910 brought a sense of personal grief to Mrs. Longyear which called upon all the resources of her faith to master.

She learned that the Directors had been informed that Mrs. Eddy’s son, George Glover, accompanied by his son and daughter, was en route to Boston to attend the funeral of his mother. It came as an inspiration to Mrs. Longyear’s thought to suggest to the Directors that she house the Glover family during their stay in Boston. Their train was stopped at a station near Brookline, thus avoiding the phalanx of reporters awaiting them at the terminus.

This considerate service to her Leader may have turned Mrs. Longyear’s attention to the importance of historical accuracy about her. Details attesting the essential nature of a person may be forgotten or distorted, once that person passes from human sight, unless friends and associates put them in permanent form. She came to regard as paramount the factual record of the events of Mrs. Eddy’s earthly sojourn. The more complete it could be made, the less opportunity would there be in succeeding centuries to fabricate tissues of imagination in order to vilify or sanctify her.

It took some years for these thoughts to mature. Three extensive trips abroad, the last around the world in 1912-13, interrupted her Boston activities, but served to bring her into touch with Christian Scientists in England, Paris, and even Hong Kong and the Philippines. She vividly appreciated the worldwide nature of the Cause, and felt that she wanted to contribute whatever she could to provide accurate and factual historical information for future generations about its Discoverer and Leader.

Mrs. Longyear enjoyed making trips by automobile and went as far as Buffalo in 1908. Wherever she went she looked up former students of Mrs. Eddy and urged them to write their reminiscences. The documents received were filed in a black cardboard box with ten or twelve drawers which sufficed until the end of World War I.

Some sort of organization had to be developed to maintain and catalog her rapidly growing mass of historical material. A large collection of books on religious thought and exegesis had been acquired through the years, especially since the Longyear round-the-world trip when they had had an opportunity to look into Eastern gropings for the Truth. In 1920, they formed the Zion Research Foundation and Library with an important endowment whose purpose was to provide comment and shed light on the origins and development of Judean-Christian thought through the ages to its logical and inspirational culmination in Christian Science. This step prepared the way for the cataloging of the numerous reminiscences she had requested from early workers, for the conservation of other historical material connected with Mrs. Eddy and her family, and for the maintenance and exhibition of portraits of Mrs. Eddy’s early students which Mrs. Longyear was commissioning and collecting.

Following her historical leads, Mrs. Longyear collected material on the life and forebears of Dr. Asa G. Eddy, and sought out the houses where Mrs. Eddy had lived and worked during the years of her search and eventual discovery. By relying on her understanding of Christian Science, she eventually found herself the owner of four of the houses, those at North Groton, Rumney, Amesbury, and Swampscott.

The scope of the deed of trust creating Zion Research Foundation proved insufficiently broad to permit its taking title to the historical houses or disbursing funds for their restoration and maintenance. After much prayer and heartsearching, Mrs. Longyear in 1923 determined upon the creation of another enterprise which she named Longyear Foundation. (Thus Longyear Foundation took over the collection relating to Mrs. Eddy which had been assembled under the Zion Research Foundation aegis.)

The strengthening of Longyear Foundation was Mrs. Longyear’s primary concern in her later years. She met the Foundation’s problems as they arose and sought their solution by applying to them her understanding of Christian Science. She sincerely welcomed the creation of a department of historical records in The Mother Church administration, for she was certain that in the true history of the movement there could only be corroboration. She was convinced to the depth of her being that the idea of Longyear Foundation was a right concept, and would continue to serve the purpose she felt she had been guided by Truth and Love to initiate.

To read part 1 of this series, click here.