Mary Baker Eddy embraced the whole world in her prayers. And during her lifetime, Christian Science spread to many countries through the healing, teaching, and lecturing activities of her church.

Grateful hearts often prompted people to bring or send Mrs. Eddy gifts from their home countries. One day in 1907, a little girl from Australia stopped by the house of John Salchow and his new wife, Mary. It was next door to Mrs. Eddy’s Pleasant View property in Concord, New Hampshire, where Mr. Salchow had been working as a groundskeeper for several years. The girl had something special that she wanted to give to Mrs. Eddy.

“I remember when she arrived at Pleasant View she would not let anyone see what she had,” Mr. Salchow later wrote. While the girl was talking with Mrs. Salchow, “finally, she opened the box a crack and let her have a peek.”1

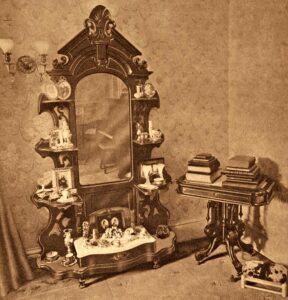

What was inside? Seashells. And where did they end up? According to Mr. Salchow, they were displayed on Mrs. Eddy’s whatnot, a carved set of walnut shelves framing a mirror. When Mrs. Eddy moved in 1908 to Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, the whatnot and the seashells came with her and were placed in her second-floor sitting room known as the Pink Room.

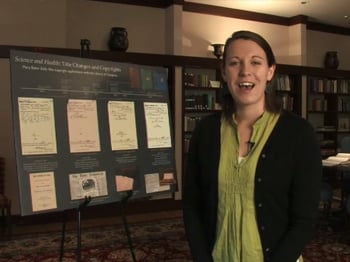

As a Longyear researcher, questions starting with “I wonder” often crop up as I am reading historical documents. So when I encountered this anecdote, my first question was, “I wonder if we have those shells in our collection?” I found some historic images of Mrs. Eddy’s whatnot and confirmed that it displayed shells. Then our Collections team helped me dig further. As it turned out, we did have shells in the collection, and seven of them had, in fact, been displayed in the Pink Room.

The generous curator of the Bailey-Matthews National Shell Museum in Sanibel, Florida, helped us identify these shells. They range from a bright orange Thorny Oyster to a sea snail known as Ramose Murex. Two of the shells—a Great Green Turban and a Mule Ear—appear to have been immersed in acid, a process designed to give them a polished look, implying they were purchased.2 They are relatively common shells around the world, but many of them can be found in Australia.

So, who were this girl and her parents? Research led me to the Gibbs family of Sydney, Australia. Although their story does not conclusively prove them to be the source of the shells, it is a rich one and well worth telling, full of demonstrations of healing, faithfulness to Mrs. Eddy, and steadfast work to establish Christian Science in Sydney.

“In the year 1898 a precious jewel came into our home,” wrote Charles H. Gibbs in the Christian Science Sentinel. “That jewel was the Christian Science textbook, ‘Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures’ by Mary Baker Eddy. Although a sufferer for many years from various ills, I was not seeking the physical healing of Christian Science but rather looking for more light about God, man, and the universe.” As Mr. Gibbs continued to read, however, he was healed of chronic indigestion and liver trouble, a “weak chest,” and seasickness, which he’d struggled with all his life.3

Born in Victoria, Australia, in 1856, Mr. Gibbs grew up on a family farm north of Melbourne and spent some years as a young man raising livestock in Western Queensland, in Barcoo Shire at Cooper’s Creek. It was an area so remote that the journey to Ipswich, where his wife’s parents lived, required travel by steamer, coach, and even a camel! His wife passed away after the birth of their third child, and the children went to stay with their grandparents, though they kept in close contact with their father.4

Mr. Gibbs’ second marriage was to Alexandrina Caroline Elizabeth Munro in 1891, and the couple settled in Sydney, where he left the farming life behind and likely pursued land development.5 Alexandrina was the daughter of a church architect, and she continued attending her own church for a time after her husband took an interest in Christian Science. “I had to travel the first few miles of my road from sense to Soul alone,” he wrote.6

The Gibbses had two children of their own—Sybil and Charlie Eric, known as Eric—who were under five when their father found Christian Science.

The healing of seasickness proved important to Mr. Gibbs’ progress in Christian Science, for in 1899, he took a long sea voyage to attend Primary class in Boston with Julia Bartlett, one of Mrs. Eddy’s enduringly loyal students.7 While there, he joined The First Church of Christ, Scientist (The Mother Church) and made his way to Concord, New Hampshire, capturing the attention of the Concord Evening Monitor. “Among the visitors present at the Wednesday evening meeting in Christian Science Hall last evening,” the paper reported, “was Mr. Gibbs, from Sydney, Australia, who had traveled ten thousand miles to learn more of Christian Science and to visit the home of its revered Leader, the Rev. Mary Baker Eddy.”8 And in the following months, that long trip bore fruit: Mr. Gibbs’ Christian Science treatments healed his father, Henry Gibbs, of heart trouble by the end of that year.9

It had been less than a decade since the first copies of Science and Health and Christian Science periodicals had arrived on the Australian continent.10 Small groups had begun studying and meeting in Sydney, Brisbane, and Melbourne, with a few individuals receiving instruction in the United States and starting to practice Christian Science healing.11

Returning from the United States, “I decided to give up every other occupation and to devote all my time to my Father’s work,” Mr. Gibbs wrote. He applied to open an office in a large building in Sydney, but the owners were “indignant that I should ask for it for such a purpose.” It took convincing proof of his social standing—a letter from the mayor—to get his foot in the door. “They then allowed me to have an office on the understanding that I would leave at any time if requested to do so,” he noted, but his steady flow of patients must have satisfied them.12 It was fitting that tenax propositi, meaning “tenacious of purpose,” was the Gibbs family motto.13

Alexandrina Gibbs began to study in earnest after about a year, noticing the good effects Christian Science had on her husband and their young daughter, Sybil. The little girl herself persuaded Mrs. Gibbs to start attending Christian Science services, held at first at the home of William and Harriet Virtue.

“Mother, if it does me good it will do you good; come along,” she told her. Mrs. Gibbs did, and found there “spiritual uplift … riches that can never be taken away … peace of mind.”14

In her Message to The Mother Church for 1900, Mrs. Eddy commented on the reach of Christian Science “in the five grand divisions of the globe; in Australia, the Philippine Islands, Hawaiian Islands; and in most of the principal cities … .”15 That same year, the Sydney Christian Scientists began holding Wednesday evening testimony meetings. Miss Bartlett responded to the news with encouragement, expecting they would soon need to move to a public hall. “[Y]ou will be glad to know I mentioned you all to [Mrs. Eddy] and your good work in Australia,” she added in a letter to Mr. Gibbs.16

Mrs. Eddy had been recognized just the week before by the governor of New Hampshire at the inaugural Concord State Fair. “It seems that the world is beginning to see something [of] what she is,” Miss Bartlett continued. “I never saw her look so beautiful as when she took her carriage that day in response to the Governor’s invitation.”

She also sent “a kiss to the little ones.” In a P.S., tacked on after receiving another letter from Mr. Gibbs, she added: “I was interested in your little girl’s case of healing of her little brother. Is it not beautiful for a child to grow up in this way. Her pure thought makes her a transparency for Truth to shine through.”

In December 1902, First Church of Christ, Scientist, Sydney, was formally established, although its meetings took place in several halls before the congregation built an edifice. Meanwhile, Christian Science had spread to Western Australia and various inland communities as well.17

Mr. and Mrs. Gibbs were hungry for more instruction in Christian Science, so in May 1903, they took their children on a long voyage to the United States. Relying on Christian Science made travel more harmonious for Mrs. Gibbs, who had previously suffered from severe seasickness. This time, she later wrote, “I completed the voyage without being ill once, although the weather was very rough.”18

During their visit, the family attended the Annual Meeting of The Mother Church and saw Mrs. Eddy speak to about 10,000 Christian Scientists who had taken up her invitation to gather at Pleasant View on June 29.19

“[T]he words of our Leader have meant and will mean more to us than we can express,” Mr. Gibbs wrote afterward. “They will go with us to help us ever on our way ‘from sense to Soul.’”20 And the family attended at least one Christian Science service in Concord, New Hampshire. Even little Sybil signed the congregation’s guest book on July 22, 1903.21

That fall, the couple attended an October class taught by Edward Kimball under the Christian Science Board of Education in Boston.22 A few years later, Mr. Gibbs’ longstanding desire to teach Christian Science led him back to Boston for the December 1906 Normal class. Its members came “from nearly every quarter of the earth.”23

This time, the family’s journey to Boston included a stop in Canton (now Guangzhou), China. There, Sybil and Eric purchased for Mrs. Eddy a butterfly curio made of blue kingfisher feathers and silver, which their guide told them was made only in Canton.24

Japan was likely their next port of call. They traveled from Yokohama to Canada, arriving near the end of October.25

During this visit, the Gibbses spent at least some of their time in Boston at 158 St. Botolph St., near The Mother Church and just down the street from Miss Bartlett’s home.26 Miss Bartlett occasionally visited Mrs. Eddy. Could she have asked to bring the family along with her one day? To fit with Mr. Salchow’s recollection about the shells, the visit would have had to take place in 1907, because he and Mary did not wed until Dec. 31, 1906. The first three weeks of January would have provided the opportunity, and Sybil would have been 11 years old.27 The Gibbs family left Boston in late January, and by early February they headed west on a ship from British Columbia to Honolulu.28

Although it is not clear when, at least one member of the Gibbs family did meet Mrs. Eddy in Concord, according to Irving Tomlinson, who assisted her there and in Chestnut Hill. His diary entry for July 5, 1910, notes: “Showed letter from a student, Mrs. (C. H.) Gibbs of Sydney, Australia, containing postcards of places of beauty in that island continent. Mrs. Eddy was much pleased, and requested that they be placed in her post card album. She asked if she did not know student and when (I) told of her visit to Concord (she) said that she thought she remembered her. I said—how beautiful to know of the world-wide love and gratitude to the Discoverer and Founder.”29

As Christian Science continued to grow in Australia, Mr. Gibbs helped correct misunderstandings in the press about the religion and its Leader, serving as a local Committee on Publication.30

He also helped bring Christian Science lecturers to Australia. Bicknell Young spoke twice in Sydney to large audiences on a tour which took him around the world in 1908. These were the first such lectures in Sydney. Mr. Gibbs and the Sydney lecture committee wrote to Mrs. Eddy that the audiences “listened with rapt attention to his clear and simple statement of facts regarding Christian Science and its Founder. There is already abundant evidence of a wide-spread interest in Christian Science having been aroused, and of many misconceptions having been swept away.”31 And Mr. Young reported upon his return: “The Christian Scientists in Australia are staunch and true. Their church organizations were founded upon the healing of the sick and sinful, and because that work goes on the churches are growing in numbers and influence.”32

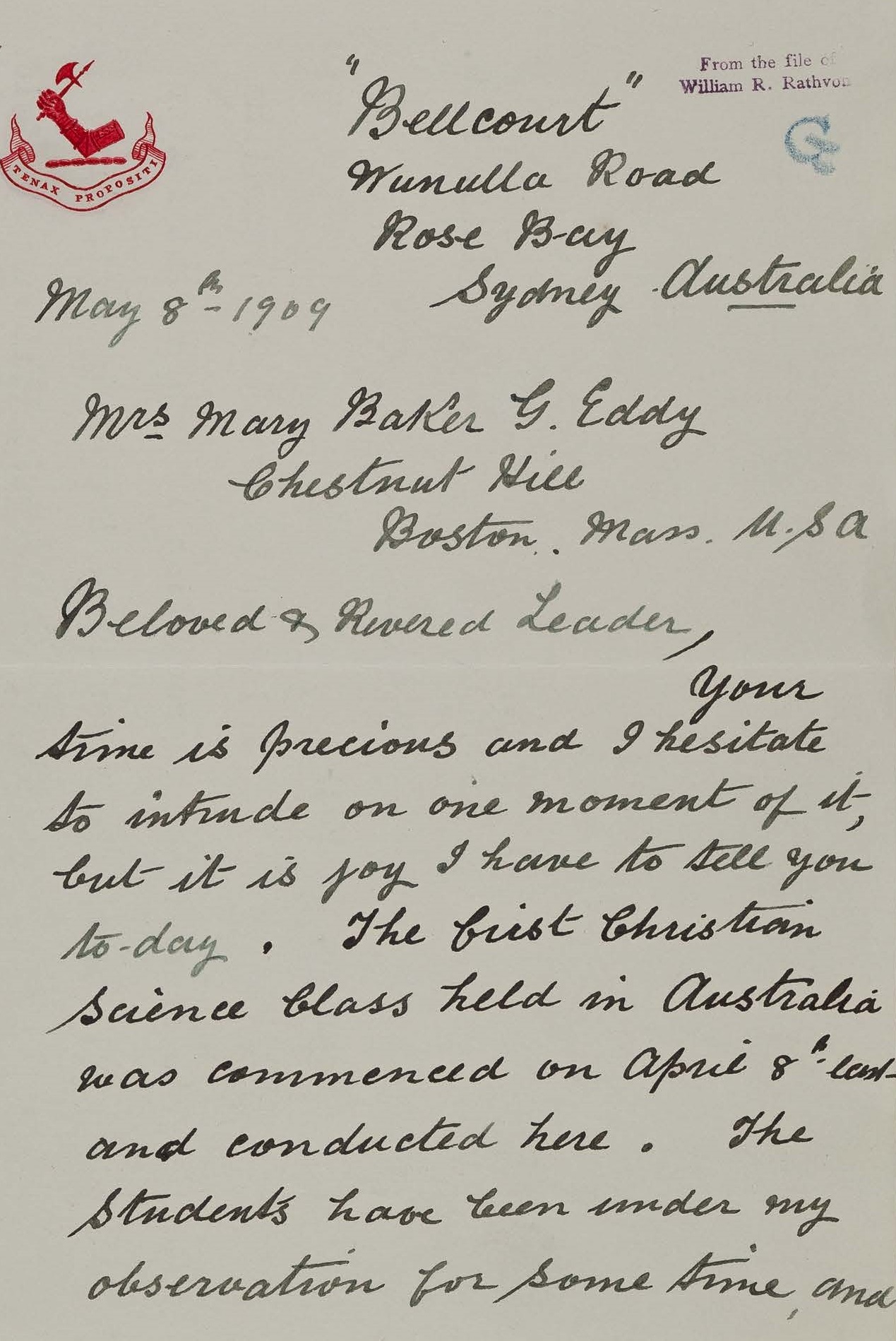

April 1909 brought a momentous occasion: Mr. Gibbs taught the first Christian Science primary class in Australia. His students had “the child spirit and humility like Mary of old that will sit at the feet of Christ and listen,” he wrote in a joyous report to Mrs. Eddy afterward.33

His wife also wrote to Mrs. Eddy about solid healings the students had experienced before attending class. While supporting the class with her prayers and looking out on the glittering waves from their home near Rose Bay, Mrs. Gibbs thought of Jesus calling Peter and Andrew to be fishers of men. “I thanked God the same Truth was here today doing the work,” she wrote.34

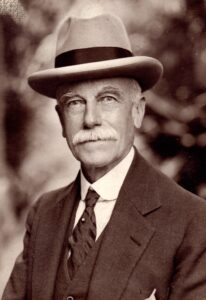

From those consecrated beginnings, Mr. Gibbs continued his work in Christian Science, teaching scores of students, corresponding with several of Mrs. Eddy’s students, introducing lecturers such as William R. Rathvon, and paying at least two more visits to the United States. When he passed away in 1941, there were about 50 practitioners in Sydney listed in The Christian Science Journal, and many others throughout the country.35

The beautiful gems of the sea displayed on Mrs. Eddy’s whatnot, whether or not they came from the loving hands of the Gibbs family, serve as symbols of the waves of support and affection that flowed between Mrs. Eddy and her followers on the far side of the globe.

“The progress of the work in Australia is a subject that always enlists the attention of our Leader when presented, and anything pertaining thereto is always welcomed,” Mr. Rathvon, who was serving as Mrs. Eddy’s secretary, wrote to Mr. and Mrs. Gibbs in one of several letters in 1909.36 That summer, the Sydney church also reported their progress to Mrs. Eddy. Her reply: “It would seem as if the whole import of Christian Science had been mirrored forth by your loving hearts, to reflect its heavenly rays over all the earth.”37

Stacy A. Teicher is a research associate at Longyear Museum.

This article originally ran in the fall 2022 issue of the Longyear Review, a free publication for members. If you’d like to join and receive this print newsletter, please click here.