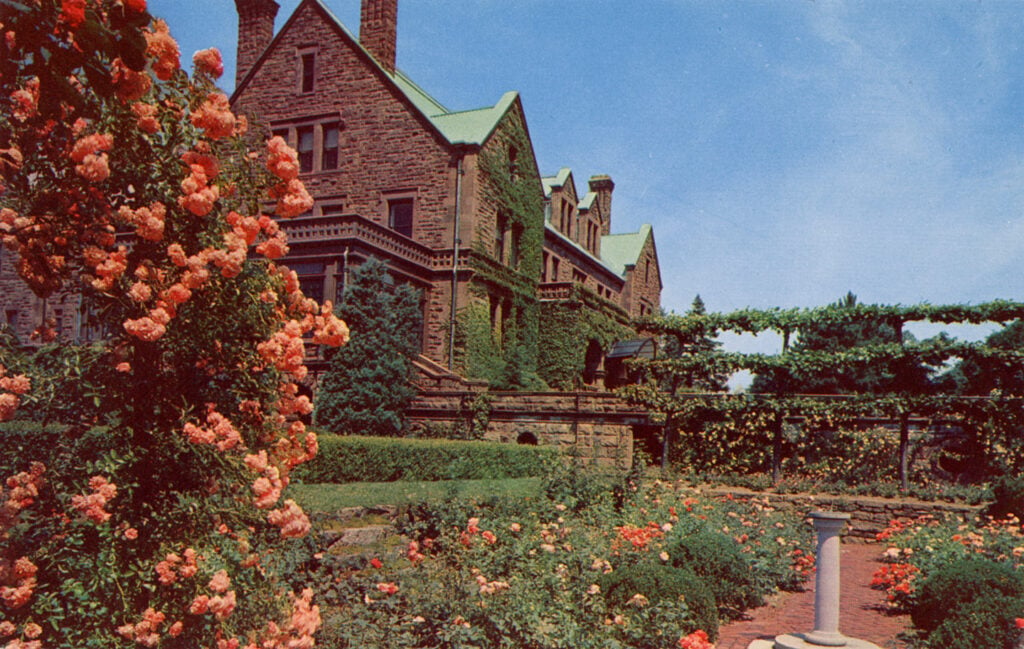

From 1937 to 1998, Longyear Museum was housed in the former home of founder Mary Beecher Longyear on Fisher Hill in Brookline, Massachusetts. Over those 60 years, the Museum trustees faced the gargantuan task of maintaining the 88-room mansion and its expansive, manicured grounds. The mansion was sold in 1997 with the intent of constructing a purpose-built museum, which had been Mrs. Longyear’s dream from the beginning. As part of our coverage of the Museum’s 100th anniversary, former staff member Timothy Leech looks back on the process of packing up the collections as Longyear prepared to take a huge step forward.

On a June morning in 1997, I sat in the library of Longyear Museum, the oak-paneled room where Mrs. Longyear had once kept her early collections. I was there for a job interview with the Museum’s director.

Prior to my arrival that morning, I had visited several times, both during a childhood trip in 1979 and after I moved to Boston, in 1990. Memories of those visits include seeing the marvelous collection of portraits of early Christian Scientists, the Baker family spinning wheel, and the skiff that Canadian Christian Scientists donated to Mrs. Eddy for use on the Pleasant View pond—exhibited in the mansion’s former bowling alley in the basement. I had an overall impression of the grand but quiet residence.1

During my interview, the director clearly explained the reason that Longyear was moving out of the mansion: The building needed costly repairs and maintenance just to make it suitable as a house, without taking into account any upgrades to the security, climate control, and exhibit spaces that were desired for preserving and displaying museum collections. Selling the property would provide seed funds for purchasing and developing a new location that would offer several advantages. It would open the way to build a state-of-the-art museum, give better access for those coming by public transportation and car, and dispel the on-going tendency to directly associate Mary Baker Eddy with the old mansion. (Mrs. Eddy’s final home at 400 Beacon Street in Chestnut Hill, also a large stone mansion, was located about 2.5 miles away from the Longyear property in Brookline.)

Before wrapping up the interview, the director offered me a job assisting with packing and preparing to move the historical collections.

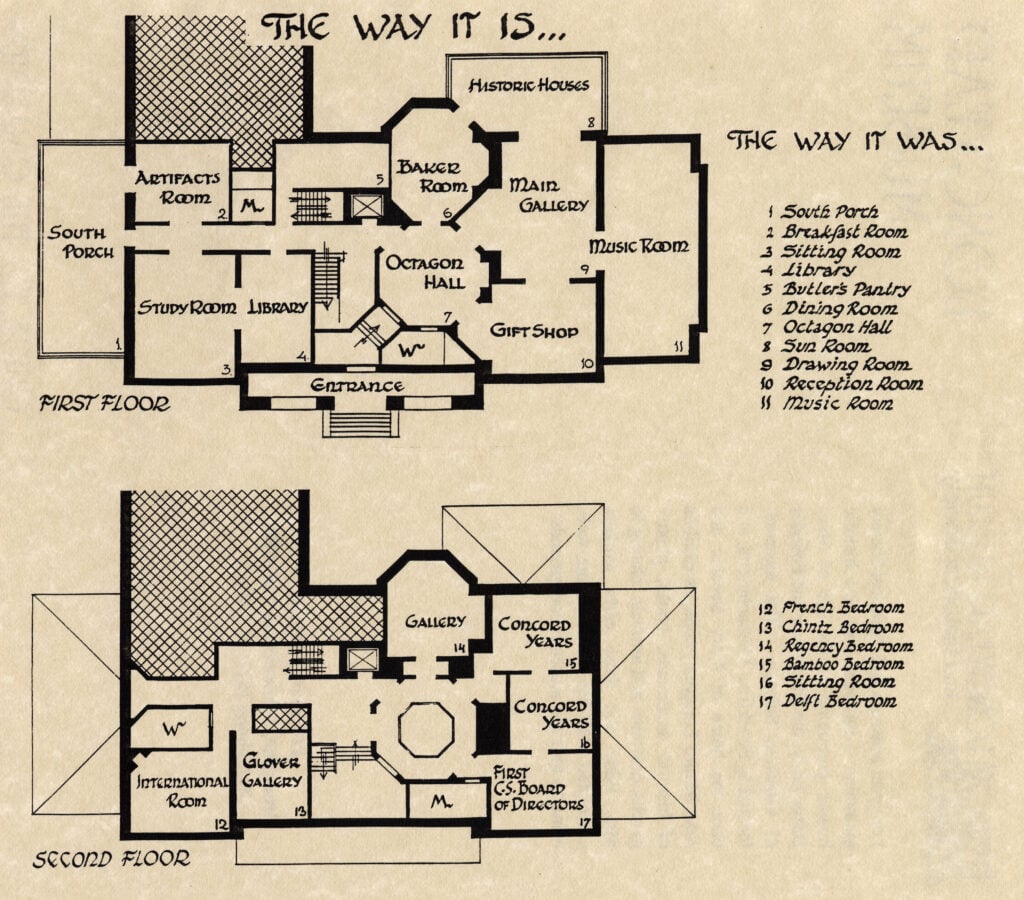

When I started my work, my supervisor, the Museum’s assistant curator, gave me a thorough tour of the mansion. This was very useful, as my work soon took me to every room of the house. The mansion had three floors, plus a basement and an attic. After Mrs. Longyear’s passing, the Museum had been set up with exhibits and public spaces in the principal rooms of the mansion on the first two floors, as well as in some of the spaces in the basement. Museum staff and support spaces were allocated to the wing that had been home to “back of house” activities—mainly kitchens, laundries, and servants’ areas—during Mrs. Longyear’s day. The administrative and management offices were on the second story of that wing, with the curatorial and collections spaces on the floor below, in what had been the food storage and preparation areas. By the time I started, most of the exhibits had already been dismantled and many of the key artifacts had been secured in crates with custom-fit padding. I had to concentrate to not get turned around in the mansion’s maze-like corridors.

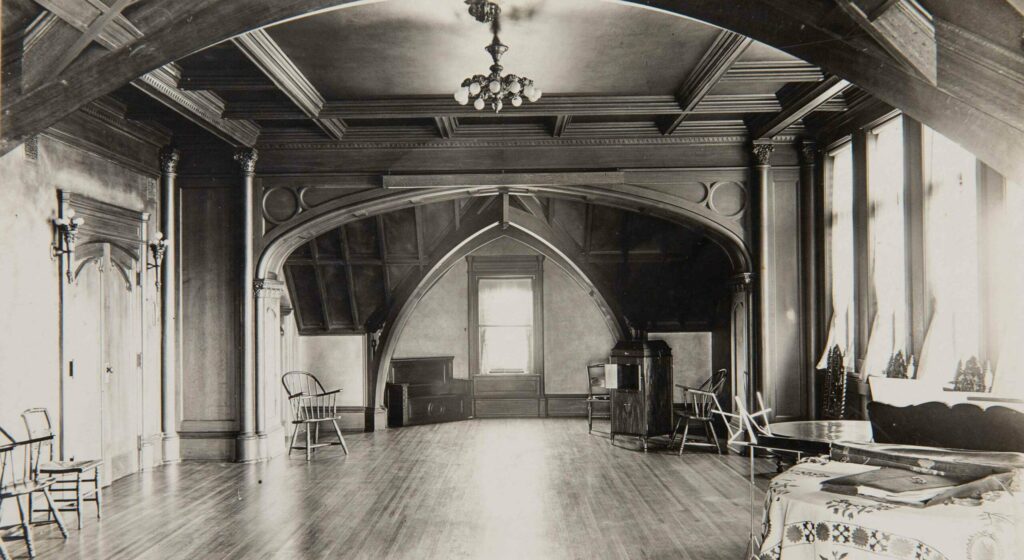

On my first day at work, I was assigned to disassemble and pack labels and photographic reproductions from the exhibit in the former bowling alley. After that, I was sent to the third floor “Gothic Hall” (or ballroom) to retrieve a piece of furniture. This paneled room, which covered the full width of the house, had been formerly used for a variety of recreational functions, but it had been given over to storing larger furniture. In order to get to the item I was searching for, I had to shift a chair out of the way. I had started to receive training on handling museum collection items, but I hadn’t gotten specific instructions on moving chairs. Rather than finding my way down two long flights of stairs to my supervisor’s office, I pulled on some cotton gloves that I was already in the habit of carrying and lifted it carefully by the seat. I was later grateful to be reassured that I had handled it correctly.

Shortly after I started working at the mansion, Longyear’s management realized that an inventory prior to packing the museum’s collections needed to be conducted in a thorough and detailed manner—with a scope that was much larger than originally envisioned. In addition to taking the inventory, each item would be photo-documented and all those images, along with the other information, would be entered into a computer database. To accomplish the monumental task, many other workers were rapidly brought on board: a librarian to process books, a photographer, a person to handle the paintings, someone to scan the historic photographs, and several workers to assist with the archival collections.

Before long, the mansion was buzzing with activity, with stations set up in various rooms for the inventory and packing work. Breaks and lunch times—in areas set apart for food in order not to attract mice or insects—became social occasions filled with laughter and joy.

Within a few weeks of starting my job, my supervisor determined that it was appropriate for me to work, when needed, in the vault. This was the storage facility for the archival collections, photographs, and the smaller artifacts and art objects. The vault had been installed in the space that had originally been the Longyear family’s meat locker—a highly secure, well-insulated location. The vault was entered through a locked anteroom (the original pantry), which was also used for collection storage. The vault door was just like the entrance to a classic bank vault—solid steel with a central combination lock.

Once I entered the vault, I found myself surrounded with floor-to-ceiling shelves that were absolutely packed with archival-quality acid-free boxes. The center of the space was filled by a worktable that had larger boxes stored below and was mostly covered by objects that were too fragile or complicated to pack away. A narrow path provided access around the perimeter of the central table. Lighting in the vault was minimal, in order to protect collection objects from damage. I would eventually learn that such a crowded space was not ideal for a museum collection, because there was no room to add any new acquisitions, and the cramped quarters increased the likelihood of accidentally bumping into something.

My first assignment in the vault was refiling some documents and photographs that had been used for a publication. With any sizable collection, it is absolutely critical that the items be well-organized, and everything is returned to its proper storage location after use. Otherwise, there is a substantial risk that the desired item won’t be able to be found the next time it is wanted. As the inventory project got into full swing, it soon became my duty to pull out boxes of archival documents for cataloguing into the database and boxes of photographs for scanning. We used rolling carts to bring out the materials being worked with in the morning and returned them to the vault at the end of the day.

Despite our top priorities of conducting the collection inventory and packing for the move, we understood that we also needed to devote some time to looking ahead to when the new museum building would open. It would need exhibits. Early on in my job, one of my assignments was to go through the bound volumes of the first issues of the Journal of Christian Science to identify the pieces written by Mrs. Eddy, photocopy those items, and arrange them into chronological binders.2 (The online presence of the Christian Science periodicals, jsh.com, did not debut until 2012.)

Mrs. Eddy provided most of the content for the first several issues of her Journal. Most of these pieces are now available in Prose Works, but I found it really interesting to see them in their original context, especially since the subsequent process of editing often removed some of their sense of urgency and immediacy. Mrs. Eddy often wrote these items very quickly, in the midst of revising her textbook, teaching in her college, and working to establish the cause of Christian Science on a firm foundation.

In addition to this work with the Journal, I also had the special privilege of working with some of the manuscript documents that Mrs. Eddy had written with her own hands. We always took the greatest care, whenever we handled her letters and other manuscripts. I found it especially challenging in this work to decipher the handwriting. With practice, patience, and mentoring from colleagues, it gradually became easier to understand the handwriting. Dealing with penmanship (or orthography) is one of the types of puzzles that often makes historical work so fascinating. From the beginning, we were all unified in our commitment that Mrs. Eddy’s own words—the primary sources—would be the foundation of Longyear’s historical exhibits.

My months of working in the Longyear mansion seemed to fly by. I learned a lot very quickly, and I always kept very busy. About a year after my Longyear journey began, it was time to move out of the mansion. Anyone who has ever moved out of a house will have some idea of what this experience was like. But moving a museum is far more complicated than moving a family from one house to another. The quantity of material to be moved, as well as the imperative need to properly care for the historic collections, elevated the project to one of incredible complexity. Months of planning were devoted to preparing for the move.

One way I contributed to these preparations was locating a supplier for vast quantities of bubble wrap which we needed to use for wrapping the collection of portraits. An internet search led me to a vendor in western Massachusetts who sold and shipped to Longyear four rolls of bubble wrap. Each one contained 1,000 feet of wrap and was 4 feet wide. It was quite a sight watching the semi-trailer truck inching its way up the back driveway of the mansion to make this delivery. Once we received the rolls, we were dismayed to find out that they were so wide that they couldn’t fit through the service door we generally used. Fortunately, we were able to carry them around to the front and bring them in through the imposing main entrance.

Difficult choices had to be made. Specialists at handling fine arts packed and moved the most important and fragile items, but dealing with all the collection items this way would have been prohibitively expensive. Instead, a commercial moving company was engaged to move most of the furniture and artwork, as well as our office fittings and equipment. Some items would go to warehouse storage, while others would go to different areas within the museum’s temporary quarters on Huntington Avenue in Boston.3 Everything had to be carefully labeled, tracked, and accounted for. All of the work we had put into our inventory database began to really pay off.

Supervising the crew of movers and directing them through the mansion seemed like coordinating a parade. After months of preparation, everything was cleared out very quickly. Before we said our final good-byes to the old Longyear mansion, staff members were allowed to select some of the household items that were not part of the museum collection to keep for themselves. Among the mementos I still treasure are one of the wooden bowling balls and a 1920s-era lightbulb from the Gothic Hall, which still works.

Seemingly in a flash, the mansion had gone from a building that was totally packed with all the things that had to be moved to a vast empty space. We looked around the now-empty rooms, and our quiet voices echoed through the corridors. It was a wistful moment akin to a school graduation—it marked both the end of an era but also the beginning of a new and progressive chapter in the history of Longyear Museum. It brought to mind Mrs. Eddy’s words in Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures: “When outgrowing the old, you should not fear to put on the new” (410). Our next tasks involved organizing our temporary workspace, so that we could continue preparing for the joyous day when Longyear would again be open to visitors.