Everyone who came to Amesbury always went to see John Greenleaf Whittier, Sarah Bagley told her new tenant and teacher, Mary Baker Eddy (Mrs. Patterson at the time). Wouldn’t she like to go see him, too?

“No,” Mrs. Eddy responded. “I have no particular desire to see him.”

Well, if she changed her mind, Sarah told her, “you must see him soon for he is ill and will probably not live long.”

Hearing these words, Mary didn’t hesitate. “Well, said I, if that is his condition I will go and see him and help him.”1

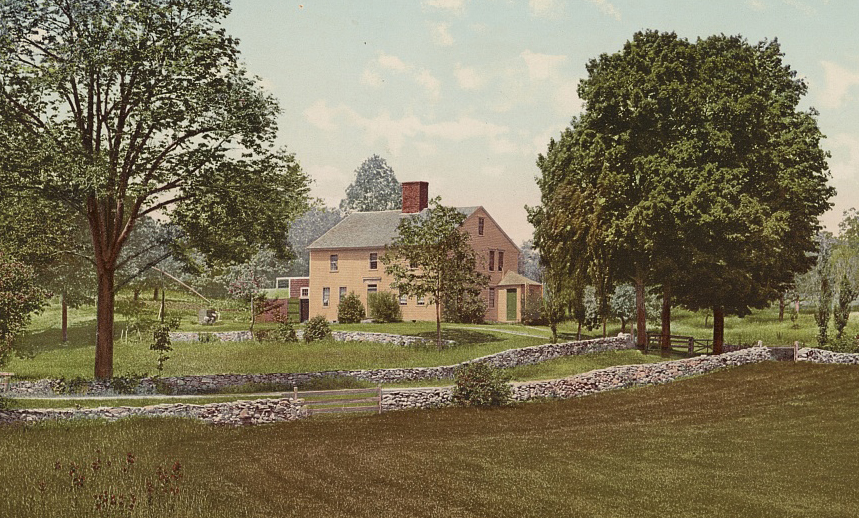

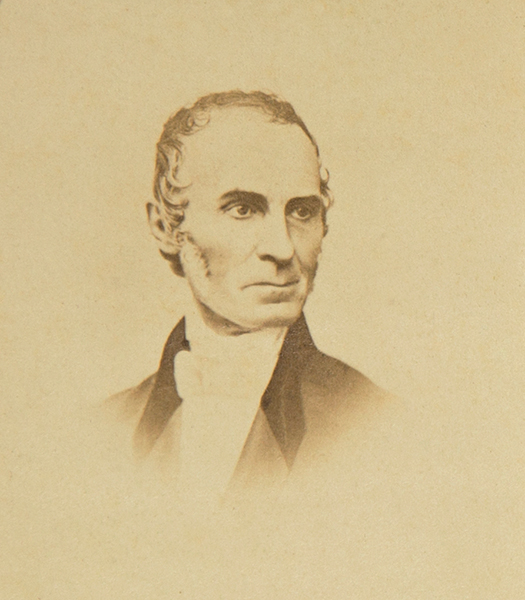

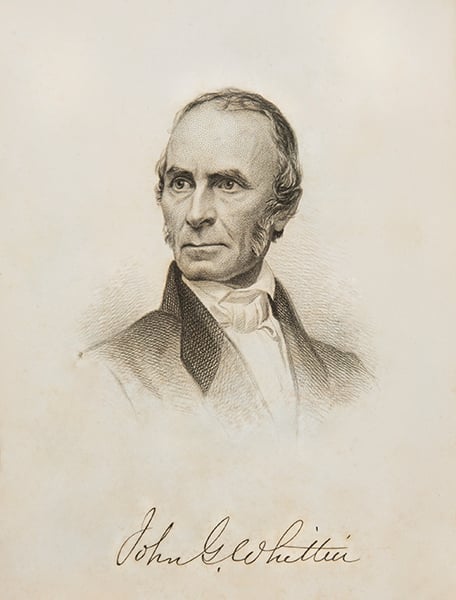

John Greenleaf Whittier, the famous Quaker poet who fervently advocated for the abolition of slavery, lived just down the road from Sarah Bagley, a distant relative and a friend of his sister Elizabeth’s.2 Their small town of Amesbury, Massachusetts, sandwiched between the New Hampshire border and the placid Merrimack River, proved a captivating landscape to this 19th-century writer.3 Although born in the neighboring town of Haverhill, after Mr. Whittier moved to Amesbury in 1836, he never left.4

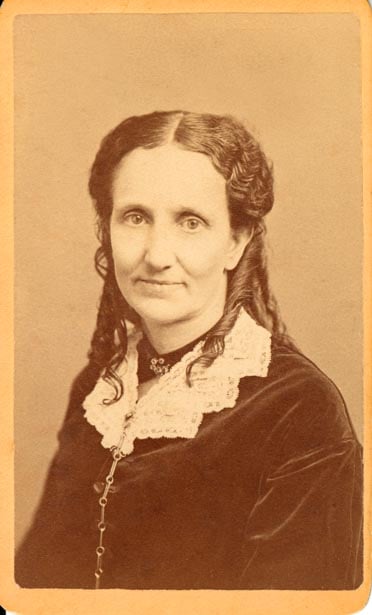

By 1867, Amesbury had become home to another writer, though this one did not stay nearly as long. That autumn, the woman who would come to be known as Mary Baker Eddy traveled north from Lynn in search of a quiet place to study her Bible and write. She found what she was looking for at the home of Captain Nathaniel Webster and his kind-hearted wife, who was known locally as “Mother Webster,” thanks to her generosity in offering shelter to those in need. Mrs. Webster gave her new boarder a room with a view of the river5 — the Webster home was near the ferry port — and a desk at which to write.6

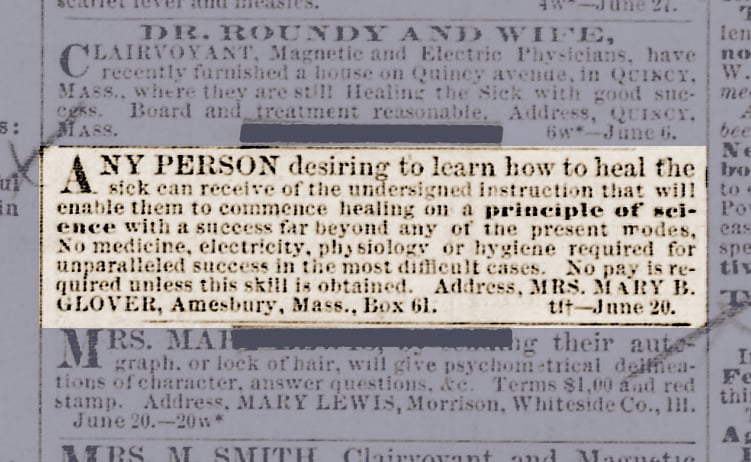

The previous year had been a momentous one for Mary. Not only had she experienced a transformative healing after a severe fall on icy pavement — a recovery brought about by spiritual means alone7 — but she had also taught her first student. Sadly, her husband had also deserted her, and she was struggling to make ends meet. Now, this boardinghouse in Amesbury would become, for a time, a refuge and a workspace.

“Writing, writing, writing, she was always writing, the sheets falling to the floor beside her,” a fellow boarder at the Webster’s home observed. “She seldom went out, she saw few people; she simply sat and wrote.”8 A neighborhood policeman confirmed this report, adding, “Never did I see a lady write so fast and so much.”9

Mrs. Eddy was busy pondering her mission, studying the Bible, and making “copious notes” of her findings.10

“I sought the solution of this problem of Mind-healing,” she later reflected, “searched the Scriptures and read little else, kept aloof from society, and devoted time and energies to discovering a positive rule.”11

This “positive rule” would be thought and re-thought, worded and re-worded for nearly a decade, until it finally took form in a finished book.12

Meanwhile, though, when the Websters’ son came home in June 1868 to make arrangements for his family’s annual summer vacation, Mary and the rest of the boarders were evicted. Fortunately, there was room nearby at the Bagley house, where Sarah Bagley lived with her widowed mother. Mary was shown to a small upstairs bedroom overlooking Main Street. Sarah was intrigued by her new lodger, who was not only reading and writing, but also teaching and healing!13 She determined that Mary and her famous relative had to meet.

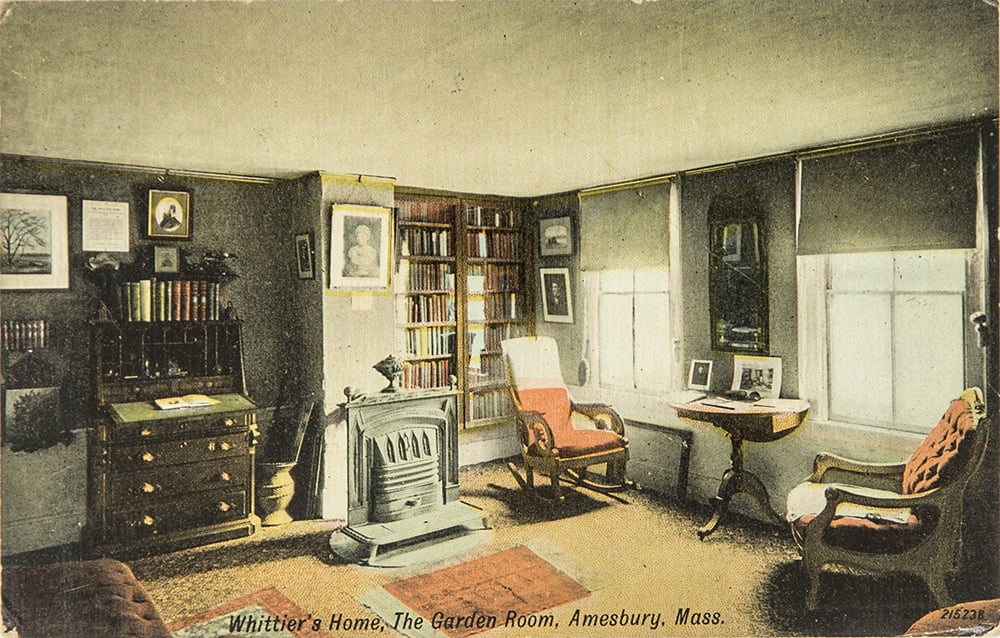

Mary and Sarah had only to walk a mile through town to reach Whittier’s house. They found the poet in his study, surrounded by brimming bookshelves and walls adorned with portraits of great men and women — poets, authors, ministers, politicians, and army officers — from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to Ralph Waldo Emerson, Marcus Aurelius, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and more. John Greenleaf Whittier lived directly across from the Friends Meeting House, which was very convenient for his Quaker friends, who huddled around him in concern on this particular day.

Whittier sat helplessly by the fire, coughing incessantly, unable to speak louder than a whisper. Mrs. Eddy sat patiently and calmly beside him.

“The atmosphere is more comfortable outside than inside,” she said, motioning toward the windows and the warm summer day beyond. She continued talking with him “in the line of Science,” and soon noticed a change to his pallor. “By and by his countenance changed and the sunshine of his former character beamed through the cloud and his friends sat wrapped in interest in the truth that I presented. When I rose to go he came to me with both hands extended and said, ‘I thank you Mary for your call, it has done me much good’. . . . The next day he walked down to the village and was well.”14

Whittier must have heard something that resonated with him and prompted him to thank his visitor with such sincere appreciation. Years later, members of his family would recall him speaking about Mrs. Eddy with high praise, even talking about her with members of the community — including the local grocery driver.15

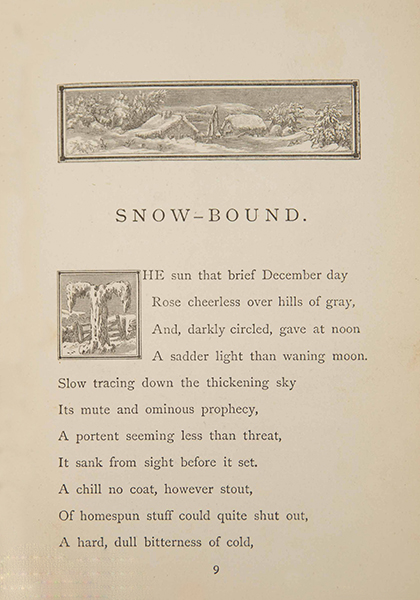

Whittier’s writing certainly resonated with Mrs. Eddy. She’d been a lifelong fan of his poems, including the one he wrote the same year that she experienced her landmark healing. Snow-Bound: A Winter Idyl, Whittier’s famous narrative-poem, was a sensation when it first appeared in 1866. The author himself was surprised by how popular and beloved this work became.16

Set in his hometown of Haverhill, Massachusetts, Snowbound nostalgically recounts a typical New England homestead in the dead of winter: the children collecting kindling for the fire and feeding the animals in the barn while a storm is brewing; the entire family looking forward to a few nights of storytelling by the fire with mugs of hot cider.17 The verses drew on Whittier’s own childhood memories of growing up on a working farm, with seven members of the family living under one roof (Whittier’s parents, a brother, two sisters, and a maternal aunt and paternal uncle), and Snowbound was dedicated to the members of his own household.18

By the time the book appeared, however, Whittier and his brother Matthew were the only surviving family members. A sense of melancholy fills the pages, although not without glimmers of hope:

We tread the paths their feet have worn,

We sit beneath their orchard-trees,

We hear, like them, the hum of bees

And rustle of the bladed corn;

We turn the pages that they read,

Their written words we linger o’er,

But in the sun they cast no shade,

No voice is heard, no sign is made,

No step is on the conscious floor!

Yet Love will dream, and Faith will trust,

(Since He who knows our need is just,)

That somehow, somewhere, meet we must.19

Produced by the highly-esteemed University Press — the same printer that Mrs. Eddy would eventually use when publishing later editions of Science and Health20 — Snowbound sold briskly and helped make Whittier a household name. After reading it, Mrs. Eddy was moved to draft a short poem of her own, titled “Lines On Reading Whittier’s Snow Bound.” Never completed or published, the lines nevertheless shed light on how deeply Whittier’s words and sentiments touched her:

But through times chinks thou let’st in light

My curtains hast uprolled

And from the chill and shadowy night

The chariot wheels of old

Roll back the morn the dewy morn

With sunshine on its breast

When those were here who now are gone

And would they might now loving come

All silently as thought

To look upon my labor done

And see ‘twere wisely wrought 21

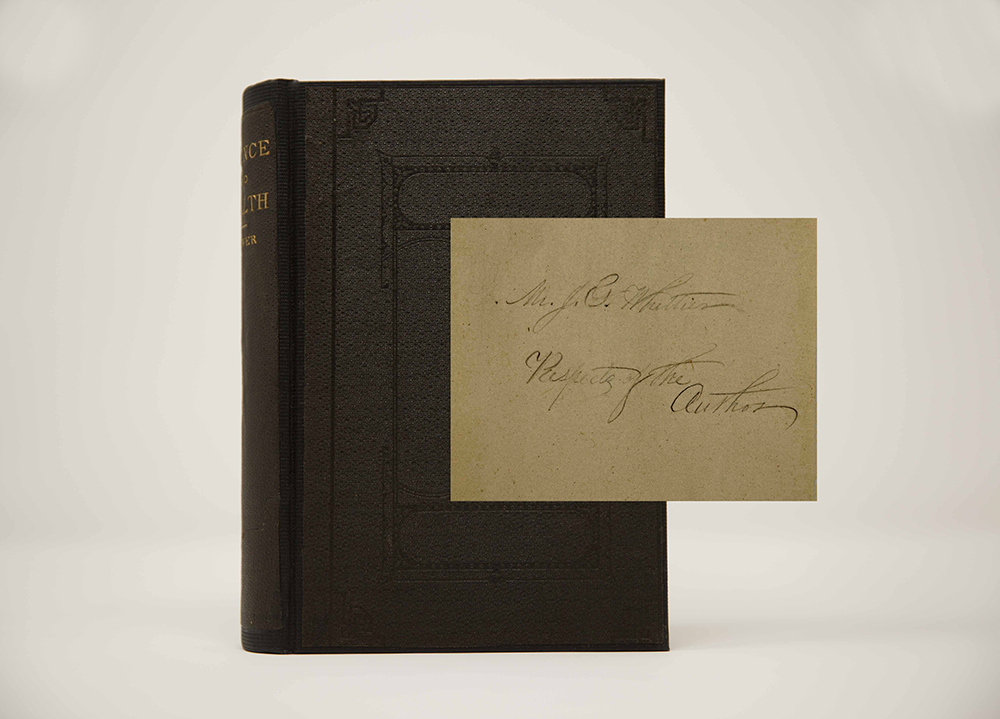

The work to be done, which doubtless must have felt like “labor” at times, kept Mrs. Eddy speedily writing. In 1872, she sent Whittier a copy of “Questions and Answers in Moral Science,” an early teaching manuscript about her discovery22 — which he read and sections of which he praised.23 After Science and Health was published a few years later, she followed up by sending him an inscribed copy of the first edition. It was still among his belongings years later after his passing.

Mrs. Eddy’s admiration for Whittier and for his words stayed with her as well. Over the years, she had clipped his poems out of literary magazines and pasted them into scrapbooks. Interestingly, the same year that she sent him a first edition of Science and Health, Whittier wrote a poem that speaks to Christian healing, and “The Healer” would eventually find its way into the Christian Science Hymnal:

So stood of old the holy Christ

Amidst the suffering throng;

With whom His lightest touch sufficed

To make the weakest strong.

That healing gift He lends to them

Who use it in His name;

The power that filled His garment’s hem

Is evermore the same.24

Mrs. Eddy once referred to Whittier as the “grandest of mystic poets,” one whose words captured the precise character of Christ Jesus that she was also trying to elucidate in her writings.25 Although the two writers had their differences, Mrs. Eddy certainly felt that Whittier’s messages were important enough to share with her readers. Eight of Whittier’s poems were turned into hymns in the Christian Science Hymnal,26 and more than a dozen of his poems were published in the Christian Science Sentinel and The Christian Science Journal. While Whittier never thought of himself as a hymn-writer per se, he couldn’t think of any form more worthy of his words. “A good hymn is the best use to which poetry can be devoted,” he once wrote.27

Mrs. Eddy also cherished a painting of Whittier’s rural homestead sent to her as a Christmas gift some years later, in 1890, by Chicago Christian Science practitioner and amateur artist Bradford Sherman.

“I look at Whittier’s Birthplace, an oil painting by Bradford Sherman, beautifully framed,” Mrs. Eddy wrote in The Christian Science Journal, “and wonder if ever poet and painter met more warmly with pen and brush in so frigid a scene as this illustration of the inimitable poem ‘Snow Bound.’”28

Mrs. Eddy loved the painting so much that she hung it in the guest room at Pleasant View, her home in New Hampshire, and took it with her when she moved to Chestnut Hill in 1908, where it graced Calvin Frye’s office.29