During the early twentieth century there were a number of architects in Europe and America who believed that buildings could reflect ideals and help to perpetuate them. Two of these men, Bernard R. Maybeck and Hendrik P. Berlage, designed edifices for branches of the Church of Christ, Scientist. The two churches have become famous in their own right as landmarks in the careers of architects who had a major influence on their contemporaries. Maybeck designed First Church of Christ, Scientist in Berkeley, California, and Berlage designed First Church of Christ, Scientist in The Hague, Netherlands.

Hendrik Berlage had a long and productive career in the Netherlands, stretching from 1882 to 1934. He became famous throughout Europe when he completed the Stock Exchange in Amsterdam in 1903. But it could be argued that the Christian Science church he designed in The Hague in 1925 was the most complete objectification of his philosophy in the later years of his career. The church also shows his deep interest in architectural developments in the United States because there is some evidence that he was greatly influenced by Louis Sullivan’s design of St. Paul’s Methodist Church in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. The congregation that chose Dr. Berlage as their architect probably got a good deal more than they bargained for because they gave him an opportunity to mix his outlook with the needs of a faith that had come to Europe from America. Berlage was an idealist who believed in the brotherhood of all mankind as opposed to the carnage of World War I, which raged around his native Holland.

In 1911 Berlage came to America on a brief lecture tour which permitted him to meet the famous architects Louis Sullivan and William G. Purcell. For a number of years the Dutch architect had admired the work of Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, and at long last he was able to see the buildings that had been published in architectural magazines in Germany and Holland. The trip was a great success in every respect. Berlage was able to speak to a variety of audiences in New York, Chicago, Boston, Minneapolis, and a few other cities. He saw the buildings that best reflected the American architecture of the Prairie School, including Louis Sullivan’s designs for the Methodist Church in Cedar Rapids. Shortly after his return from the United States Berlage printed some articles and a book that summarized his discoveries. He freely admitted that the best work of the Americans was equal to the finest new buildings in Europe.

As World War I left the Netherlands physically and culturally isolated, Hendrick Berlage developed some of the ideas that stressed the need for a greater sense of brotherhood for all mankind. He designed a startling project for a Pantheon of Mankind that included tall towers and radiating geometric paths. He had used towers before in the corners of his larger buildings, but now the tower was to become a central feature of the design.

Berlage believed that central towers could have a symbolic meaning, and he had been quite taken with Sullivan’s tower on the Cedar Rapids design. “Rightly starting from the recognition that a Protestant church has to be an ideal meeting-room, he (Sullivan) made the auditorium in the form of a semi-circle, placing the tower in the center, that is on the place of the pulpit. With this he therefore broke completely with the tradition of Protestant church-building, which has never quite been able to free itself from the form of the original Christian church, namely the Roman Catholic, where the tower by its special place receives a higher, ideal significance than that of bell tower alone.”

About six years before the work on the Christian Science church in The Hague, Berlage prepared a design for the Gemeentemuseum, a municipal museum. Here he did not use towers, but reflecting pools of water helped to increase the size of the building and offered visitors many vistas of a succession of domes and walls. This particular building was not completed until the 1930’s in a much reduced form. However, the church design executed in 1925 reflected all of the trends in Berlage’s career, and the building was completed as he had designed it.

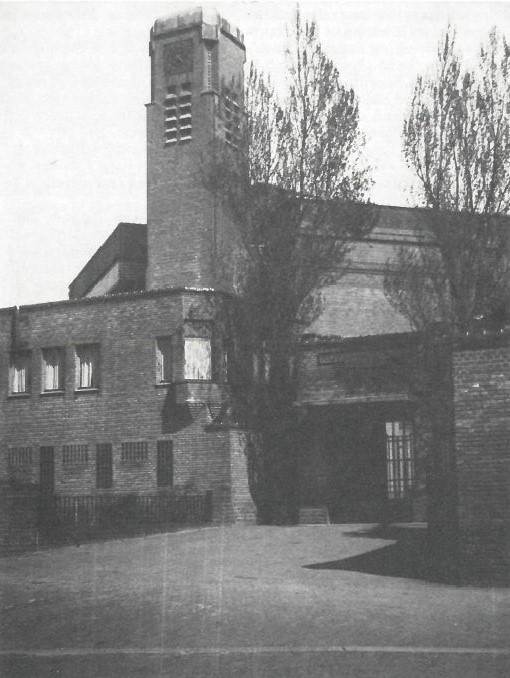

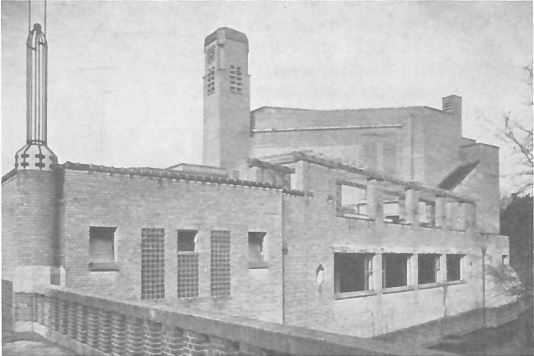

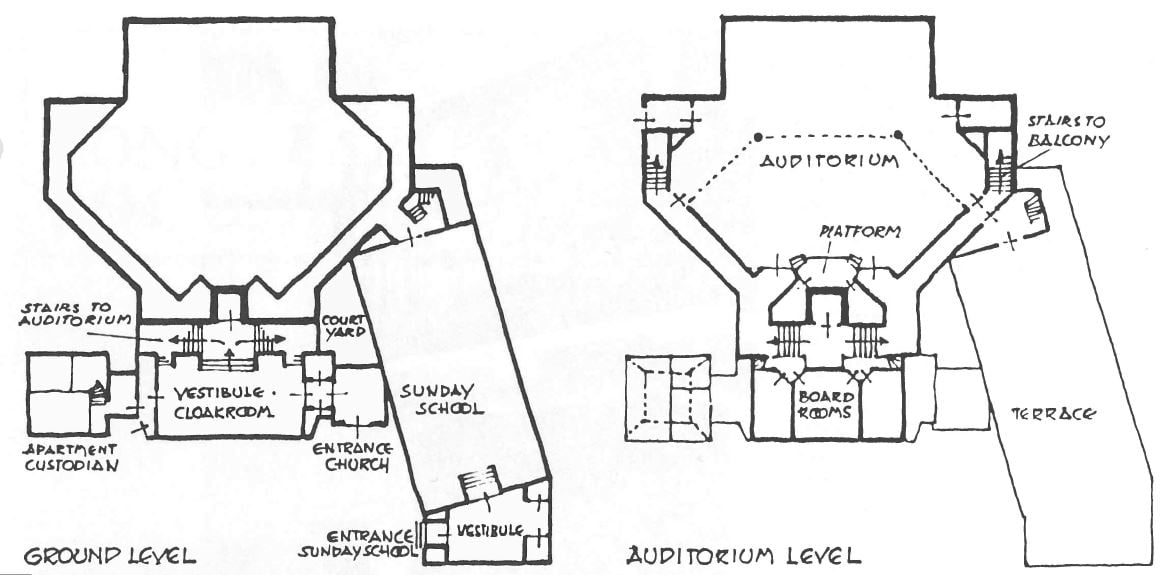

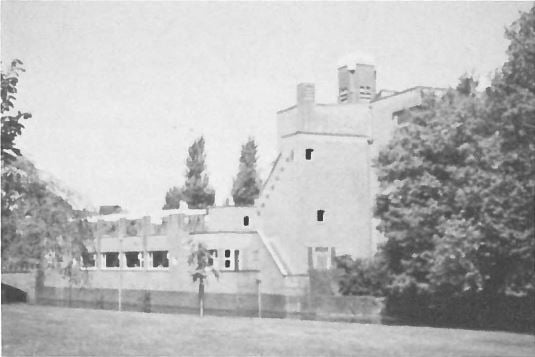

The Christian Science church is sited on a slope bordering a stream, giving the visitor a reflected view of the Sunday School wing of the edifice. In addition, there is a strong central tower placed above the readers’ platform, in keeping with Berlage’s ideas about the Sullivan church in Cedar Rapids. It seems peculiarly appropriate that the most influential architect in the Netherlands would design a church building that embodied ideas he had picked up in the United States fourteen years before. Perhaps he saw in the Christian Science services the kind of simplicity and idealism that permitted him to move away from the conventional idea of what a church should look like.

By the time the Christian Science church commission came along Berlage had been able to watch a younger generation of architects in Holland develop two contrasting styles. One group designed large public housing facilities that had bold decorations done with brick, stone and tile. These apartment blocks were punctuated with towers and unusual doorways; sometimes figures and messages appeared on the walls of these large buildings. Another group of architects had proposed that the twentieth century called for a new style that was clean and geometric. Simplicity was a keynote in their work, which stressed the use of right angles, large windows and plain white walls. Both groups were “modern” in their outlook, and both owed something philosophically to the earlier work of Berlage. It turns out that his edifice in The Hague really reflects the ideas of Berlage’s earlier career and the outlook of the newer generations as well.

As viewed from the main entrance, the church has the angular outline of the Amsterdam structures of Berlage and his younger contemporaries. Inside the auditorium one sees the clean lines of bright tones of the modernist group. In addition the floor plan expresses the ideals of the American architect Sullivan in its concentration on the center tower, both as a focus inside the building (where the readers stand) and outside where the visitor would have heard the bell ringing.

There is color, both in the landscaping and in the bricks and windows, but it is a muted tone. Some of the windows are large, particularly in the Sunday School wing which borders the water. Other windows, especially in the auditorium have plain glass bricks with a row of green glass bricks along the outer edge.

Above the Sunday School there is a wood pergola that hints at a roof garden looking out over the water. As the visitor walks around the church, different masses come into view, often outlined by rows of bricks. Even the rear of the auditorium and upper portions of the balcony make a bold profile in contrast to the tower.

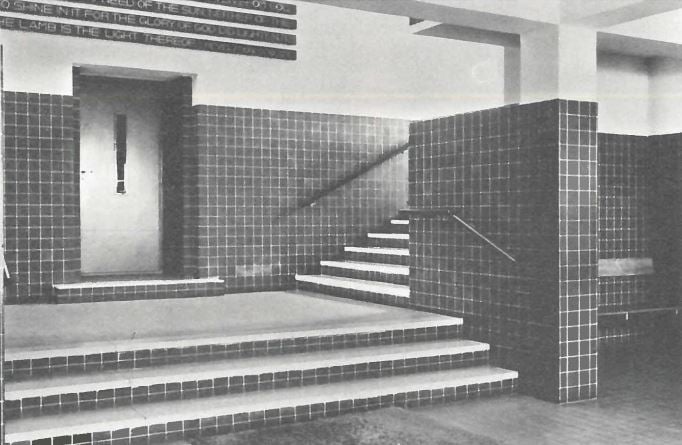

The entrance to the church brings the visitor up to a remarkable dedicatory plaque placed in the courtyard October 31, 1925. It is done in blue tiles with texts from Isaiah and I Corinthians. The vestibule is covered with tiles up to about eye level, while the ceiling is plain white. On the stairs to the auditorium there is a quotation from Revelation about the Heavenly City, complete with a symbolic motif in the ceiling. At this point the stairs lead into the main auditorium in such a way that the visitor comes out on the lower level fairly near the readers’ platform.

The auditorium is the principal space of the whole design, and it expresses the idea of a temple by the inclusion of colors in the organ-case, mainly blue and crimson, as mentioned in II Chronicles where the veil is described. The visibility is excellent because the readers’ platform is high and the seats in the rear are steeply banked. The readers’ desk is made up of a tile base with two metal cylinders with the lecturns. All of the focus is on the center of the room, just as Berlage had noticed in Sullivan’s design for the Methodist Church in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. All the light in the auditorium is from windows high on the wall, as is the case in the readers’ rooms. Dr. Berlage maintained that leaders of a church should receive their light from above.

In the Sunday School room the atmosphere is quite different because the large windows on one side of the room open out to the water and the parkland beyond. There is a great sense of the presence of nature in this space. The side walls have a hint of alcoves, thus giving each of the classes a certain identity.

The architect had a copy of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy for his own use while he was designing the edifice, and it appears that he found the concepts of man’s perfection appealing. Berlage’s biographers and critics agree that he was a great believer in social causes, in man’s brotherhood and in the power of ideas as a force in organizing society. Many of his most advanced designs were never built, and in some cases they were never intended to be built. But the Christian Science church in The Hague represents a mature statement by a very influential architect. All of the main elements of his approach to planning were here: careful disposition of the parts of the building, deep thought about the symbolism that was connected with a religious structure, use of water as a key element in the setting, a tower that was the functional center of the whole complex, color used in a careful way to enhance the services and the approaches to the auditorium. And he was able to use many of the materials and techniques developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a means of keeping contact with the contemporary world. First Church of Christ, Scientist, The Hague, is truly one of the finest buildings in Europe that came out of the years immediately following the first World War.