To have been a notable woman in Mrs. Eddy’s time required much of what it does today — courage, perseverance, unselfed motives, and often a singleness of thought. In the following article we have selected some of the prominent women of that period. These women shared qualities which were enriched with a great sense of love and caring for their fellow man. Most of them taught, many were mothers and wives, several were wonderful speakers, and all are still an inspiration today.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony

Though Mrs. Eddy was truly ahead of her time in her spiritual concept of true equality for men and women, the cause for woman’s suffrage was brewing during her lifetime under the direction of two rather different women — Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Mrs. Stanton (1815-1902) was an organizer. She certainly had to be since her combined work for the woman’s movement and woman’s suffrage (two distinct goals in Mrs. Stanton’s mind) and the raising of seven children kept her very busy. As the daughter of Judge Daniel Cady, she learned to probe and question. Unfortunately, her father didn’t approve of what she chose to question so she was almost disinherited. Her husband, Henry Stanton, a lawyer, wasn’t too keen on his wife’s activities, so she depended upon support from others. One was Lucretia Matt, a well-known preacher and abolitionist, who spoke at the first Woman’s Rights convention in 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York. It was here that woman’s suffrage was first demanded.

Susan B. Anthony (1829-1906) was the co-founder of the National Woman’s Suffrage Association with Mrs. Stanton. Her working life began when she taught school to help pay off family debts. She first met Mrs. Stanton in 1851 when Miss Anthony learned that women weren’t allow to speak at temperance meetings. Mrs. Stanton’s advice was not to fight but to form a separate temperance society. Miss Anthony was also an active abolitionist. They worked closely together as publisher and editor of the magazine Revolution, 1868-1870.

Both women were not afraid to rock the boat and risk the consequences. Miss Anthony was jailed when trying to register to vote in 1872. Mrs. Stanton took the cause a step further when she ran for Congress in the 8th district of New York City in 1866. She was not jailed. Instead, she received 24 votes.

Harriet Beecher Stowe

When Abraham Lincoln met Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) he reportedly said, “So this is the little woman who wrote the book that made the big war.”

Mrs. Stowe, like so many of Mrs. Eddy’s contemporaries, was a dedicated school teacher. She married the widowed professor/clergyman Calvin Stowe of South Natick (now Natick), Massachusetts in 1836 when she was 25. She raised six children. Her interest and talent in writing developed when she temporarily returned to her father’s house in Cincinnati and helped her brother, Henry Ward Beecher, edit The Cincinnati Journal. She then saw that she could write stories to add to the family purse. In fact, she wrote primarily for money, not for her need for artistic expression. In 1850, the Stowe family moved to Brunswick, Maine, where Mr. Stowe taught at Bowdoin College. There, Harriet became passionately involved in the anti-slavery movement. The combination of her writing and her political feelings culminated in the publication of her most famous work — Uncle Tom’s Cabin — in 1851. She was her own publicist and sent copies of her book to everyone from Charles Dickens to Queen Victoria’s Prince Albert. Two years later she traveled through Europe and was highly praised in Great Britain. She continued writing, contributing to the new magazine Atlantic Monthly and publishing more novels, including The Minister’s Wooing (1859).

Lilly Martin Spencer and Mary Cassatt

Art has always been a somewhat unconventional occupation for men and women. In the 19th century, not many women painted. But there were a few American ladies who dared.

Lilly Martin Spencer (1822-1902) was born in Ohio of French parents. Her parents were active in social reform so there was little uproar when she decided to be an artist. In fact she began her painting in her teens — on the family walls. She studied in Cincinnati, and later in New York. She also married and raised seven children. She concentrated on day-to-day moments in women’s lives in her paintings, and these “genre” paintings were her most popular. Though never quite able to support her family by her work, she did make a name for herself and is often included in retrospectives of women artists.

Far more famous was Mary Cassatt (1845-1926) a woman from an upper class main line Philadelphia background. Her family was not too pleased with her chosen field. Unlike Mrs. Spencer, she never tried to combine family and career. She studied abroad in Paris where she said “I began to live.” She was invited in 1877 by Edgar Degas to join a group of artists called Independents (later named by art historians as Impressionists). Miss Cassatt was capable of working in many mediums — oils and pastels. Interestingly enough, though never a mother herself, she eventually would devote more and more time to the mother and child theme, and would explore this subject in a variety of wonderful ways.

Harriet Tubman

Heroines appear throughout history, and Harriet Tubman (1820-1913) was certainly one for her time. “The Moses of her people” Mrs. Tubman was the most successful conductor on the underground railroad. She was known for her incredible courage, cleverness and ingenuity.

Mrs. Tubman, the child of Harriet Greene and Benjamin Ross, was born a slave and lived with the vivid memories of her two sisters being sold. This was a common plantation practice. After Harriet suffered some physical mistreatment, there was a rumor that the plantation was sinking and that the slaves would be sold. She and her two brothers decided to run away. Though the men turned back, she kept going on to Philadelphia. Her success inspired her to set others free. During the years 1850-60, Mrs. Tubman made 19 trips to the South to bring back over 300 slaves worth a quarter of a million dollars. Though the journeys were risky, she used wisdom and brought only the number of slaves she knew she could care for. She also incorporated Bible references to let her passengers know where she was.

She worked with John Brown, a leader who planned a slave revolt in 1859. Though the Harper’s Ferry incident failed and Brown was hung, she clung to Brown’s vision of free blacks.

She brought her last group of slaves to Canada via New York in 1861, and returned to Boston to meet Alcott, Emerson, and Lydia Maria Child. She told them and many others of her work. Mrs. Tubman was a gifted speaker, though she often had to address anti-slavery meetings under an alias as she was still considered a hunted woman. During the Civil War she served as a nurse, laundress and spy. Unfortunately, her work for the government was never acknowledged and she was unable to get a pension. Nevertheless, Mrs. Tubman certainly made her mark on history.

Mrs. Tubman married twice. First, a free black, John Tubman in 1844. Then, Nelson Davis in 1869. Her second marriage was a grand affair, even Secretary of State, Seward attended.

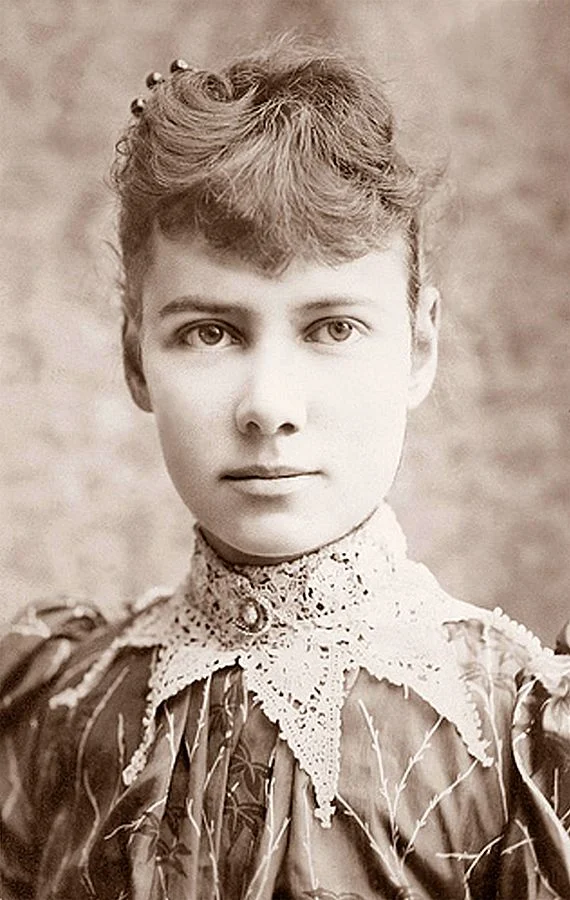

Nellie Bly

Women journalists were few and far between during Mrs. Eddy’s time though ironically Mrs: Eddy would found an entire newspaper. The profession was considered a man’s field.

There was one notable woman reporter — Nellie Bly [the pen name of Elizabeth Cochrane (1867-1922)]. At 18 she began as a feature writer for The Pittsburgh Dispatch, where the managing editor suggested she take a pen name from a song by Stephen Foster. After moving to New York in 1887 she wrote a series of expose-style pieces for The New York World including one on inhumane conditions in local asylums, which she researched by being admitted to an institution as a patient. The piece brought about needed reforms. Perhaps, she is best known for sailing from New York hoping to beat the record of the imaginary Jules Verne character Phineas Fogg (Around the World in 80 Days). She did — it took her a little over 72 days. She married millionaire Robert Seaman in 1895, but after his passing returned to her writing career.

Dorothea Dix

Social work has always received much support from women, Miss Dorothea Dix (1802-1887) is a fine example of a noble crusader with a great singleness of purpose. She was also a born teacher.

Though experiencing a lonely childhood — lacking in love and support — Dorothea never wallowed in self-pity. She spent most of her time with relatives. She lived with a grandmother in Boston, later an aunt in Worcester and there Miss Dix, at 14, successfully opened a school for young children. After three years, she returned to her grandmother’s home and educated herself to become a qualified teacher. During this time, Miss Dix experienced a broken engagement and a broken heart but once again never allowed herself to give in to her sorrows. She did become interested in Unitarianism (a far cry from her father’s Methodist teachings) and through this she met the renowned Unitarian teacher — William Ellery Channing.

She opened another school but the work was too much for her and an emotional and physical collapse followed. In 1835, she closed her boarding school for girls and sailed to England to recover. She met William Rathbone, a friend of Channing’s. He was involved in urban reform and sparked her particular interest in the human plight of the mentally ill. When she finally returned to America in the fall of 1837, she was invited to teach Sunday School in an East Cambridge jail, and there saw the horrible conditions which existed. She began to canvas the state of Massachusetts for two years and this culminated in a study with recommendations addressed to the state legislature. Her proposals were adopted.

In 1845, after traveling through nine thousand facilities and sixty thousand miles, she conceived the idea of designating federal ground — 5 million acres — for care facilities. The proposal passed both houses. However, much to Miss Dix’s disappointment, President Franklin Pierce vetoed the bill in 1848.

She decided to return to England to rest, however her “restful” vacation became a two year crusade on behalf of the mentally ill in 14 countries.

The Civil War brought her stateside, and she served as Superintendent of Nurses for the War Department. One of her nurses was Louisa May Alcott.

She continued touring and inspecting after the war and spent her last years as a guest at a New Jersey care facility.

Mary Harris Jones

Possibly the least known activist of Mrs. Eddy’s contemporaries is Mary Harris Jones (1830-1930). Though she was born in Ireland, her father later settled the family in Burlington, Vermont and it was from him that Mrs. Jones learned the “ins and outs” of railway travel which would serve her well in the years to come. She attended a teachers college in Toronto, graduated in 1859 and proved to be a natural teacher. She married a blacksmith/ organizer for the Iron Moulder’s Union in Memphis and with him had four children.

Twice her sense of home and security would be shattered. First in Memphis, yellow fever wiped out her entire family. A few years later, in Chicago, her dressmaker shop was destroyed by the great fire of 1871. She was never to accumulate any possessions after that. “I reside wherever there is a good fight against wrong,” she would say.

She began to attend Knights of Labor meetings and unofficially joined them (women couldn’t be members until 1879) and served as a recruiter. She was a fiery speaker though her demeanor was always quite ladylike.

Mrs. Jones would find herself involved in many landmark labor strikes and would always be called in to help in emergencies. She would be involved primarily with minors and it was by them she was named “Mother.” She, interestingly enough, would also organize the miners’ wives and that would often turn a strike around.

A specific concern was for the children who worked the mines. She organized the March of the Mill Children which went from Kensington, Pennsylvania to Oyster Bay, New York where President Teddy Roosevelt was staying. Today this might be called a publicity stunt, but it did its work because laws were passed in Pennsylvania to keep children out of factories until they were 14 years old.

Mother Jones was also directly involved in what some historians consider the most serious labor conflict in the United States, the Colorado Mine Field Struggle which lasted 14 months during 1913-1914. Miners were striking for an eight hour day, among other demands. However, the owners — including John D. Rockefeller, Jr. — fought back, literally. There was much bloodshed and though Mother Jones was carefully watched, she managed to stay close to the strike as a result of her working knowledge of the railways. She even met Mr. Rockefeller though that did not turn the strike around.

She continued her labor work throughout her lifetime, and when she turned 100, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. was among her well-wishers.