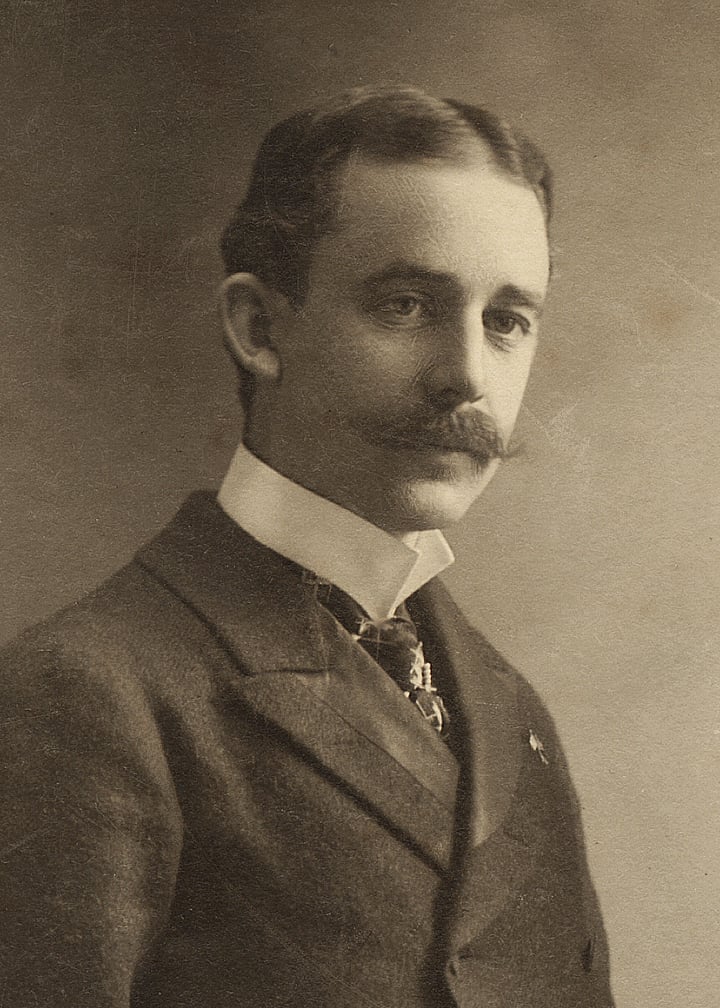

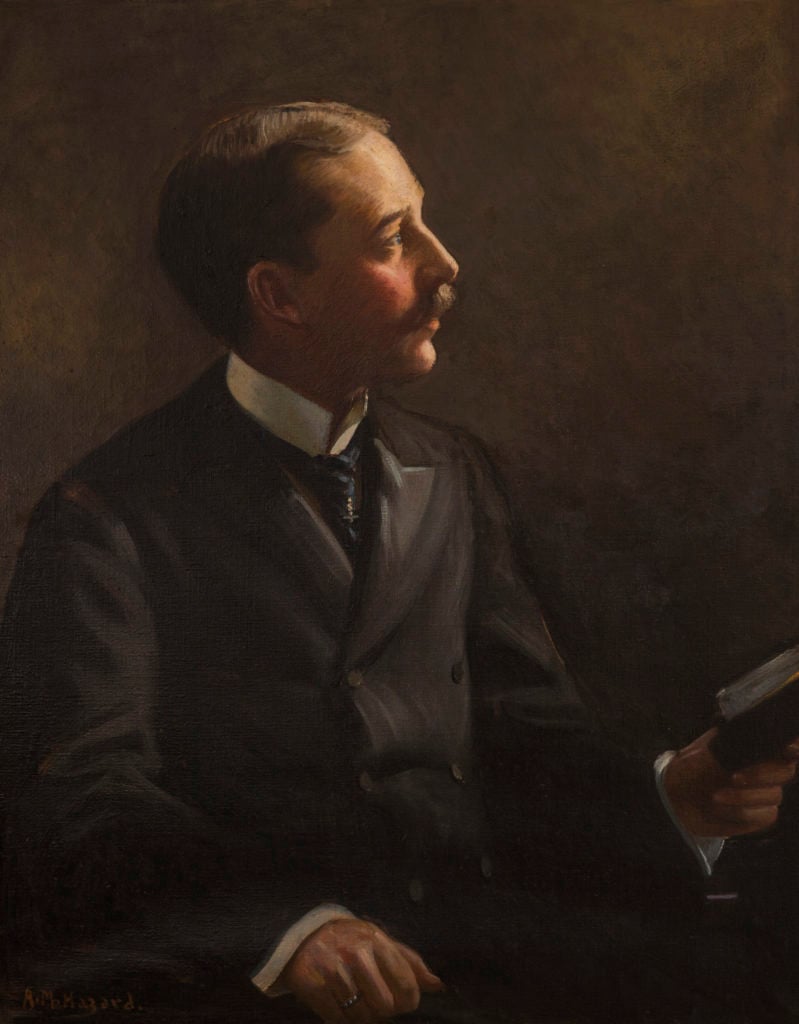

On the afternoon of December 18, 1898, an unassuming but earnest young man, still in his twenties, addressed an audience of over 3,000 people at Carnegie Hall in New York City on the subject of Christian Science. Prominent clergymen were in attendance, and a physician of the allopathic and homeopathic schools was seated on the platform. The only New York newspaper that reported the event stated that the lecturer, Carol Norton, spoke extemporaneously for over an hour and a half, and “held the close attention of his vast audience…. He declared that the philosophy of Christian Science would stand the test of time; that it proved its accuracy by its results, and demonstrated its divinity from the Bible….”1

We cannot know how the distinguished audience responded to such statements as: “The restored Church of Christ on earth is rising in our midst”; and ”…since the days of the Palestine Healer and Reformer nobody in Christendom or in any other religious world, has gone to the supreme end of pure Monotheism except Mrs. Eddy.”2 But we do know that the lecturer was “enthusiastically received,” and that he handled his subject “in a masterly manner.”3

Norton’s lecture was presented at a time when Christian Science was being viciously attacked by the press, and this was no doubt the reason that all but one New York newspaper ignored the event in their columns. Just six months later, however, it was a different story. Norton’s appearance at the Metropolitan Opera House on May 28, 1899 was reported by every major newspaper in the city. The New York Mail and Express printed the lecture in full. The Herald, the World, the Times, the Sun, the Tribune, the Daily News, all provided thorough coverage, and most of them underscored what must have been a most dramatic moment during the course of the lecture: Norton asked all in the audience to stand who had been healed in Christian Science. It was reported that of the 3,000 people in attendance, about one-third rose, and were acknowledged by “a great outburst of applause.”4 The Mail and Express noted: “…the address of Mr. Norton was such in text and temper that no honest truth-seeker, be he friendly or hostile, will care to ignore it…. Mr. Norton has certainly made the strongest presentation of the philosophy and method of Christian Science that has thus far come to public notice.”5

Carol Norton had been appointed by Mary Baker Eddy to the newly-formed Christian Science Board of Lectureship a year and a half earlier. He had endeared himself to her through his gentle, loving nature, strong moral character, writing and speaking ability, and appreciation of womanhood. Mrs. Eddy was not the only one who found Carol to be an exceptional young man. During his brief lifetime, many felt his influence for good.

Born and raised a Unitarian in Eastport, Maine, Carol early lost both his parents. As a result, his faith in God was sorely tested, particularly after his father’s passing. He writes of this experience: “My beloved father became ill, and gradually grew worse…. All this time, with the trust of boyhood, I prayed that he might be spared to us. There seemed no good reason why, just at a time when his young son most needed him, he should be taken; but, one evening after I had climbed down out of his loving arms, he slipped away from his loved ones, and I awoke to two awful facts. I was fatherless; and, God had not answered my prayers…. Had God deserted me? To my regret, my religion threw no light on the question as to why this great sorrow should enter my young life.”6 Throughout this experience, however, Carol felt that somehow good would triumph over evil, and this hope, he later saw, was “the voice of the impersonal Christ.”

Although Unitarianism failed to answer his heart-yearnings, he was befriended by a minister of that denomination, with whom he walked “hand in hand the rocky road of theology.” Other Unitarian thinkers had a profound effect on Carol as well. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his brother Samuel were cousins of Carol’s mother. In particular, Carol drank in the spirituality inherent in the poems of Samuel Longfellow, the author of many sacred hymns.

After the loss of his parents, Carol lived with an uncle and aunt in New York City. Completing his formal education at fifteen, he entered the business world. Though successful, his heart was still fervently committed to theological concerns. He never abandoned the strong moral teaching of his faith, and his commitment to church work and love for humanity led him to help meet the spiritual needs of the young men in his home town. Carol spent long hours studying religious works in his search for truth. Though unsatisfied, he never questioned God’s existence or yielded to cynicism. There must be, he felt, a divine solution to life’s problems.

After wrestling with a longstanding physical difficulty which medical treatment failed to cure, he turned to Christian Science. The first treatment healed him. He writes: “I could hardly realize it;…Life to me now had a new meaning. I was fairly drunk with the new wine of spiritual Illumination. The revelation was indescribable.”7 His eager delving into the theology of Christian Science settled for him the troubling questions about God’s nature for which he had long sought satisfying answers. He gave up his business career, and in the words of a lifelong friend, “he renounced the comforts and ease of prosperity for the limitation and privation of a reformer. He…began at the humblest phase of the work he could find as a helper in one of the Christian Science churches.”8

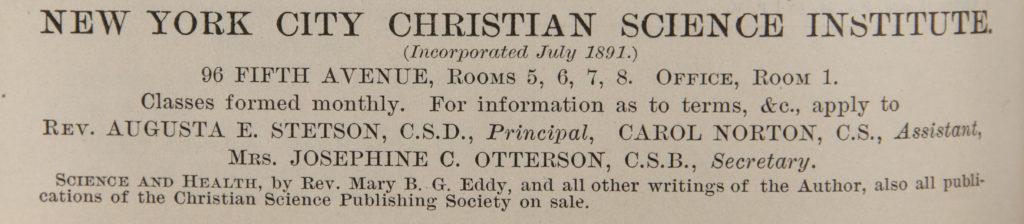

That church was the precursor of First Church of Christ, Scientist, New York City. At the time Carol united with it, Augusta Stetson was pastor of the church, as well as principal of the New York City Christian Science Institute. Carol’s name first appeared in The Christian Science Journal of February 1891 as assistant to Mrs. Stetson. Recognizing his talent and ability, she gave him opportunities to preach, lecture, and aid in the promotion of Christian Science. She even went so far as to seriously consider adopting him.9

Mrs. Eddy, however, foresaw problems arising from Mrs. Stetson’s hold on her young protege, and warned him of her influence.10 Carol ultimately severed his connection with her as assistant teacher and as Second Reader of the church. In a letter explaining his action, he wrote: “This step is essentially one of individual conviction and represents my own interpretation of the demands of impersonal Christian Science upon me at this hour…. [It] has of course meant much prayer and fasting, demonstration and prayerful thought, and I feel to-day a deeper loyalty than ever to the cause of Christian Science, its Leader, the Rev. Mary Baker G. Eddy, and the Church of Christ, Scientist,…feeling that impersonality, liberalism, individual spiritual freedom, divine democracy

and equality, consistent compassionate love, purity and chastity of thought and unity born of divine love are the cardinal and vital demands of Christian Science in this hour.”11

In 1898 Carol was invited to attend what was to be Mrs. Eddy’s last class, held in Concord, New Hampshire, after which he was given the degree of C.S.D. Another member of the class, Sue Harper Mims, described her fellow students: “There were lawyers, physicians, judges, businessmen and, what was to me the most beautiful of all, several young men of twenty to twenty-five years of age, who had given up every kind of business occupation just to become Christian Scientists…. The sweetest thing to me was to see those young men — just leaving all for Christ.”12 Carol Norton was no doubt one of those young men whose commitment to Christian Science so touched Mrs. Mims’ heart.

In January 1898, Carol — at the age of 2 7 — began his work as one of the first five members of the Board of Lectureship. His early lecture engagements kept him for the most part in the middle Atlantic states and Ontario. The individuals who introduced him were often prominent members of the community: physicians, editors, ministers, lawyers, judges, mayors, professors, and university presidents, including Hon. John H. Peck of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. A number of Norton’s lectures were held near academic institutions; and in March 1901 he delivered “A Third of a Century of Christian Science” — a strong explication of Christian Science and defence of its Founder — at Cornell University.13 In reading this lecture today, one finds it difficult to believe that it was written by a man whose formal education ended at the age of fifteen.

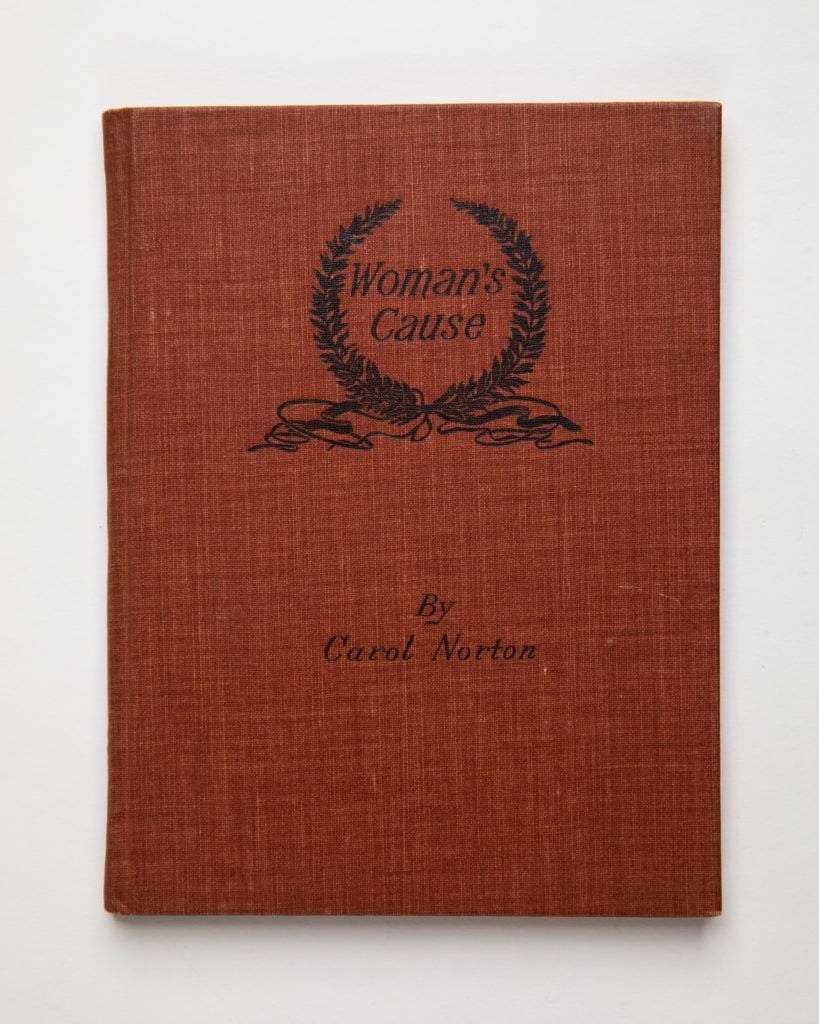

Perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of the lecture is Norton’s tribute to womanhood. His audience, comprised largely of young men, would have heard the speaker say: “The present age witnesses woman’s ascension to her rightful place as man’s equal. The highest conception that man can have of the divine Being is to think of the infinite Motherhood of God as divine Love. Can it not then be truthfully said that ideal womanhood is the scientific expression of this phase of the divine Nature?”14 Norton’s closing remarks included a loving tribute to her whose exemplification of the womanly ideal brought forth Christian Science: “Mrs. Eddy is without doubt the greatest religious reformer of the nineteenth century and the greatest woman leader in the history of religion…. To know her is to love her…. Thousands upon thousands of men, women, and children offer up a perpetual Psalm of thanksgiving to the eternal Good for the great good that has come to humanity through the career of this God-governed woman.”15

The following lines by Tennyson, a portion of which Norton used as an epigraph for his book Woman’s Cause, were quoted in the Cornell lecture:

“The woman’s cause is man’s;

they rise or sink

Together, dwarfed or godlike,

bond or free.

For woman is not undeveloped man,

But diverse ….

Yet in the long years liker must they

grow,

The man be more of woman,

she of man,

Distinct in individualities;

But like each other even as those

who love.

Then comes the statelier Eden

back to men;

Then reign the world’s great bridals,

chaste and calm.

May these things be!”16

At about this time, Norton celebrated his own personal “bridal.” On April 9, 1901, the Boston Herald announced the wedding in New York of Norton and Elizabeth Griffin of Boston.17 The marriage was performed by New York Supreme Court Justice Edward W. Hatch in his chambers, the couple letting no one know of their plans until after the ceremony. Justice Hatch, whose wife had been healed in Christian Science, had introduced Norton at a Brooklyn lecture some time earlier. The Nortons resided in New York for another two or three years, then moved to Chicago, which Carol used as a home base for his expanding lecture work. Now a “lecturer-at-large,” he was no longer limited to any particular region, branching out as far west as the Pacific coast.

Late in the winter of 1904, Carol was crossing Chicago’s State Street, when the trolley-pole of a street car became disengaged and struck his head, rendering him unconscious. Because of the severity of the injury, he was taken to a hospital. His wife and Christian Science friends stayed with him, and a telegram was sent to Mrs. Eddy. However, according to George Kinter, a member of her household at the time, this telegram and subsequent wires were kept from her in an attempt to adhere to a rule that appeared regularly as a notice in the Christian Science periodicals and in Science and Health: “The author of the Christian Science text-book takes no patients, does not consult on disease, nor read letters referring to these subjects.” Kinter, who felt that the rule should be disregarded in this particular case, was overruled, and he received the many wires from Chicago with anguish. Carol Norton passed away without Mrs. Eddy’s being informed.

A short time later, Mrs. Eddy learned of the tragedy in a roundabout way. Kinter describes her reaction: “Upon hearing [of Norton’s death], she was moved to tears, and literally wept copiously, exacting every detail and requiring to be shown all the telegrams…. And now, how shall I convey any adequate sense of the pathos with which she appealed to me to ‘follow my own intuitions another time and let her know things like that, of such moment to our Cause,’ concluding with ‘Dear Carol, oh how I love him!'”18

In a letter to Mary Beecher Longyear some twenty-five years later, Norton’s widow referred to the deep affection that Mrs. Eddy felt for “her young student,”19 and many of Norton’s associates remarked on this, as well as on the love that he felt for Mrs. Eddy. Speaking of Norton, an editor of The Christian Science Journal wrote: “Because he represented a noble type of true manhood he was keenly appreciative of the advancing idea of true womanhood, and ever held in the highest reverence our beloved Leader…. “20 And in a tribute to Norton, Alfred Farlow observed: “Everywhere he was regarded favorably and affectionately by Christian Scientists; …His clear apprehension and elucidation of Christian Science made him an excellent teacher and he was held in the highest esteem by our beloved Leader, Mrs. Eddy.”21

In a letter to Carol in 1891, she had written: “My heart is always touched by your pure goodness.”22 Clearly, the John-like attributes of this beloved disciple remained with her well after his passing. She had placed on her “whatnot” a photograph of Carol which remained there throughout her lifetime, and which may still be seen at her home in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts.

Perhaps Norton’s most enduring contribution to the Cause of Christian Science was as a writer. Twenty-five of his articles and poems appeared in The Christian Science Journal between 1892 and 1904. His style is simple, direct, and warm — but uncompromising and unapologetic. A longtime friend — not a Christian Scientist — said of Norton, “what he writes he lives,” and praised his “clear, logical mind,” and “fondness for metaphysical thought.”23 He also expressed unusual humility in, as well as about his writing, as exhibited in a letter to an assistant to Julia Field-King, who was then editor of The Christian Science Journal: “If Mrs. King will freely advise changes in this article [“Purity”] I will cut with pleasure, that is if she sees fit to use it. “24

In all his writing Norton continually emphasized the need for purity of thought and action. The term “sinless humanhood” surfaces frequently in his articles and lectures, particularly in conjunction with his inculcation of the importance of following Jesus’ example — “the divinely human life of…the Founder of the Christian religion.”25 Norton placed this Christian demand squarely on his own shoulders, as illustrated in lines from a brief statement entitled “My Life Model”: “…to emulate always the Manhood of Christ Jesus, and ever set the compass of daily life by the North Star of Womanhood revealed through the Revelator of Christian Science; …This is to be my life prayer and perpetual quest.”26

Carol Norton pursued this quest with all the fervor of his characteristically loving nature. He left a legacy of goodness that honors both himself and the Cause he so staunchly defended and devotedly served. As his Leader wrote of him after his passing: ”Tho dead he yet speaketh, for his works do follow him.”27

In Norton’s own words:

”Love knows no cross —

The glory of a spotless life

Outshines the darkness

of Gethsemane;

And o’er life’s cross-crested hills,

As with ancient Calvary,

Shines the sunset glory of a life

well lived,

Which, while telling that the

twilight cometh,

Speaks also, in finer tone,

Of the New Day coming,

Robed in glory all its own.

No night is there, no portal

But the door of Life,

Whose arch and keystone,

Strong and firm, are fashioned

As the gates of brass —

Of Purity and Love.”28