A remarkable History of Concord, New Hampshire from 1725 to the beginning of the Twentieth Century — a publication of some 1500 pages in two volumes — has been aptly summarized by a contributor thus: “I feel that the greatness of America is bound up between the swollen covers ofthis history.” And he adds, “The greatness of America is bound up in the records of quaint, homely annals of the early settlers, repositories of humble items, dragnets of facts big and little.”

As one reviews the records of this dynamic area of our country in its infant days, especially of Concord itself, with which Mrs. Eddy’s experience was so closely associated, one finds the very fiber of which America was built. Mrs. Eddy was brought up only a few miles from Concord on the same principles on which America was founded, and these were to prove of much value to her when, later, she guided with much wisdom the Christian Science movement and her followers. She was born less than fifty years after the Declaration of Independence of the American colonies from British rule. Only fifty years earlier — in 1725 — had the first steps been taken to plant a community, which was later to become Concord, on New Hampshire’s frontier which was still dangerously exposed to Indian attacks.

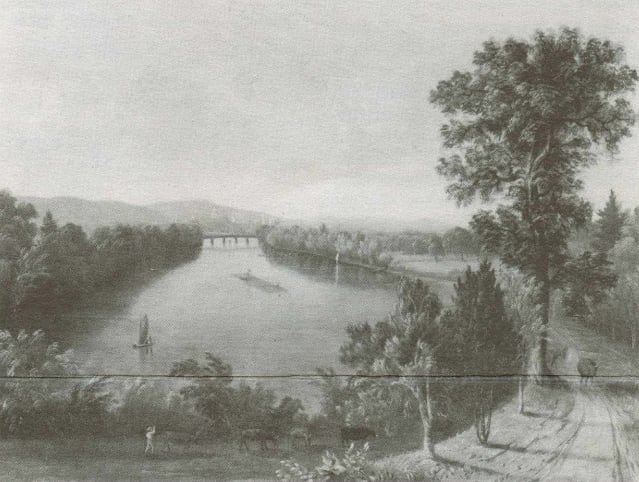

It was a verdant region with heavy forests flanking rolling lands to the Merrimack River. At that time many great trees were marked with a white arrow to indicate that they were reserved for Royal Navy masts and would be removed from time to time on order from England. Here the Penacook Indians lived and it was they who named the region Penny-Cook, or “crooked place,” from which the town Penacook derived its name — so named because of the many windings of the river at this location.

In 1725 a carefully selected group of one hundred men from Haverhill and Andover, Massachusetts applied to King George II for a grant of some seven square miles along the Merrimack River for the purpose of extending the habitable areas of the colonies, for the building of homes for themselves and their families, and for establishing a community for their descendants. In general the Penacook Indians were friendly to the newcomers. However, other tribes from near the border of Canada were often incited to raids by the French, then occupying Canada, who looked with longing on the fertile lands south of them held by the English.

The continuation of such raids was, however, considerably lessened by a campaign against the northern tribes led by the intrepid Indian ranger, Captain John Lovewell, who in 1725 carried the fight to the headquarters of these tribes at Pigwacket, now Fryeburg, Maine. He was killed along with their chief in these encounters. No further raids were made by the Indians until the French and Indian War began.

Captain Lovewell was a greatgreat-grandfather of Mary Baker Eddy. His daughter, Hannah, married Captain Joseph Baker of Roxbury, Massachusetts. The young couple rode some seventy-five miles into the unknown northern frontier to occupy lands which Hannah had inherited through a posthumous grant to her father in recognition of his services against the Indians. They settled at Pembroke (Suncook) adjoining Concord and their eldest son, Joseph Baker, crossed the Merrimack River from Pembroke in 1762 to settle in Bow with his wife, Mary Ann McNeil Moore. Here was built the house in which their little granddaughter, Mary Baker, was born in 1821, the daughter of their youngest son, Mark.

Unlike most communities in America, Concord was settled as a colony. Before acceptance, each applicant to join the colony was carefully screened as to his fitness for frontier life and his willingness and ability to function and cooperate with other members in matters touching the common interest. Thus early was established in their thoughts the value and reward of working in harmony, and the principle of community responsibility. These early settlers, known as proprietors, were all English and heirs to a sense of law and order, as well as to an awareness of moral responsibility.

In the period of relative freedom from Indian raids after the campaign of Captain Lovewell, the proprietors began building sturdy log houses, planting crops, clearing roads and establishing such facilities as they immediately needed. The first public building erected was the meeting house built of heavy hewn logs of sufficient thickness to be bulletproof. Small portholes on the sides and ends were used in defense against the Indian attacks. In 1751 it was replaced with a larger frame building on the same location, now Bouton Street. The cost of construction was paid by the proprietors and its cost of operation, including the salary of the minister, was paid by the community. No single religion was associated with this meeting house although it was predominately Congregational in character. As years passed many people in outlying villages came to its services as did the Bakers from Bow in the late 1820’s and early 1830’s.

Reverend Timothy Walker, a graduate of Harvard College, was a young man when he was called from Woburn, Massachusetts in 1730 to become the first permanent minister of Penacook Plantation, as the new settlement was designated in their charter from George II. For more than forty years Rev. Walker was not only the spiritual leader of this brave group, but advisor and participant in many advances made by the settlement. As their minister, he was no doctrinaire teacher, but on Sundays, morning and afternoon, he stressed the practical virtues of Christianity instilling in his listeners a tolerance toward all beliefs. This teaching was to bear fruit much later when Concord had acquired churches of divergent denominations. They lived harmoniously side by side and frequently shared efforts touching the common welfare. Many years later when Mrs. Eddy needed a home in which to contemplate matters concerning the Christian Science movement, it was to Concord that she went, first to 62 North State Street and then to Pleasant View.

Through the initiative of Henry Rolfe, an early settler from Newbury, the name of Penacook Plantation was changed to Rumford by the General Court of Massachusetts in 1734. The name is said to have been derived from that of an English parish from which several of the proprietors came. Rumford was made a township with the privilege of holding town meetings, but its legal rights of self-government were severely restricted by the provincial government. In 1753 the proprietors of Rumford appointed Rev. Timothy Walker and Col. Benjamin Rolfe to present to the “King’s Most Excellent Majesty, in Council,” a petition for more equitable local government and for better defined boundaries. Rev. Walker went to England while Col. Rolfe handled intermediary reports to the provincial government. Rev. Walker made three trips — in 1753, 1754, and 1762. These appeals were to bear fruit in 1765 when Rumford became a parish renamed Concord. In 1784 Concord was incorporated as a town having been given the status of a town with full governing rights. (Concord was incorporated as a city in 1853.)

The royal grant of 1725 included land on both sides of the river. As early as 1728 plans were discussed for an adequate ferry to carry persons and animals across the river, and such a service was soon in operation, continuing regular service until after the building of the first Concord bridge in 1795. Steps were taken in 1739 to start a school, and despite frequent interruptions and the hazards of the French and Indian War and the subsequent Revolutionary War, the schools multiplied and became an essential part of community life. In the absence of high schools, which were much later in coming, private academies were established throughout the state, with one at Concord on Sand Hill. It is important to note that the early proprietors had maintained from the first that education and order must go hand in hand with material growth.

Although the population of Concord was only 757 by the 1774 census, the enterprise and well-being of the town as a place to live were attracting desirable young men. Peter Green, a young lawyer from Worcester, Massachusetts cast his lot with the people of Concord and became Concord’s first attorney at law. Benjamin Thompson, a personable young teacher from Woburn, Massachusetts came to teach the community’s public school. This brilliant young man was welcomed in the homes of the leading townspeople. In the early 1770’s he married the widow of Col. Benjamin Rolfe, the man who had shared with Rev. Walker the mission which eventually brought Concord its full town status. Mrs. Rolfe was the daughter of Rev. Walker. But Mr. Thompson was a Royalist at heart and when his lack of loyalty to the pending Revolution was realized, resentment rose to such a pitch that he was forced to flee, leaving a little daughter behind with her mother. He returned to England during the Revolutionary War and in later years lived a useful life, furthering institutions of learning and benevolence in Bavaria where he was awarded many honors and was known as the “friend of man.” Thompson was made Count of Rumford (with reference to his former home) and was awarded many other honors by the ruling prince of Bavaria. After his wife’s death in 1792, his daughter joined him in Europe and as Countess of Rumford she passed much of her adult life in Munich, Paris, and London, returning in 1845 to Concord where she devoted her last years founding the Rolfe and Rumford Asylum for orphan girls, and supporting other charitable institutions.

When the Declaration of Independence was declared by the American Colonies, the people of Concord were ready with few exceptions to serve the Cause of the Revolution. Almost immediately after the battle of Lexington eighteen volunteers with their captain left for Cambridge to help their beleaguered Massachusetts brothers-in-arms. They were joined by other New Hampshire units and many fought valiantly at Bunker Hill, some losing their lives. After the battle, even though temporarily a setback, Washington’s prediction rang out, “The liberties of America are safe.”

After dissolving all allegiance to Great Britain in 1783, the American Congress met to frame a Constitution for a new country — The United States of America. It was submitted to all thirteen states; nine approvals were necessary for ratification. The document was approved by New Hampshire on June 21, 1788 in the old meeting house at Concord. This was the ninth ratification — the final vote needed to make the Constitution the law of the land. New Hampshire has long cherished this act of putting the “keystone in the arch of freedom,” as one newspaper headlined the announcement.

In 1785 a committee was appointed to name the street which began near the meeting house and followed the river for several hundred feet. At the time it was known only as “the street.” It was extended along the river southward over a mile and its width set at sixty feet, far exceeding the width of most streets in other towns at the time. The name settled upon, requiring no great originality, was Main Street, and is today as in early times the principal shopping and business street in Concord.

The town soon began expanding southward. The new post office was established in 1798 away from the north end; and new homes, businesses and small industries were building along lower Main Street and the streets radiating from it.

The year 1784 was a momentous one for Concord. By that year, it had become a town with accompanying statutory privileges, and immediately its citizens went about the business of setting up a local government. Too, the New Hampshire General Court [the title for the state legislature) indicated a desire to meet at Concord instead of Exeter or Portsmouth as it had in provincial times when the Massachusetts Bay Colony had final jurisdiction over New Hampshire. New Hampshire was now on its own as a state with its own governor. Concord was conveniently located, was an enterprising community and offered superior facilities for the accommodation of the legislature. The meeting house was again remodeled, a steeple added, and plans were made for a building to take care of the two branches of the legislature, leaving the meeting house for special occasions. When the 1784 state constitution came up for revision in 1792, these meetings were held in the old meeting house, and the work was apparently so well done that no change was made in the constitution for sixty years. The rafter, a bout 1796, the legislature began holding most of its regular sessions in Concord. Concord became the official capital of New Hampshire in 1816 and soon work was begun on the State House which finally became the home of the legislature in 1819.

When this development came to the town of Concord, it had less than 3000 inhabitants, with no hotels and few public accommodations. As a result, the incoming government officials and representatives were integrated into the community as boarders in private houses. Few houses of size and comfort were without an official paying guest. This resulted in a society of unusual interest and variety which enriched the lives of all.

The first hotel in Concord, the Eagle Coffee House, was erected a cross the street from the State House, and enjoyed a busy and colorful clientele, until it was destroyed by fire. When rebuilt it became a notable hostel, beautifully equipped and in the current decor. It was much patronized in the 1890’s and 1900’s by officialdom as well as by visitors to Pleasant View.

One must turn back a decade or two before Concord became the capital of the state, in order not to miss some of its colorful events. Early in the 1800’s Samuel F.B. Morse, who was to discover the electric telegraph in 1843, came to Concord as a portrait painter. Many of the portraits painted by him in this period are today treasured by descendants of his sitters or by museums. His inventive genius found expression in a design for a much needed second fire engine. This valued contribution is recalled in a record in the annals of Concord’s fire department. In 1818 he met Miss Lucretia Walker at a party and soon they were married. It is recorded that she was one of Concord’s “most beautiful and accomplished young ladies.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson also married a beautiful Concord girl, Miss Ellen Tucker, on September 30, 1829. Mr. Emerson had earlier given a series of sermons to the newly organized Unitarian Church members in Concord. Among the members was Col. William A. Kent, a successful business man and distinguished citizen who had come to Concord as a young man. His stepdaughter became the first wife of Mr. Emerson. It seems probable that Mr. and Mrs. Emerson may have inspired Henry David Thoreau’s week-long canoe trip from Concord, Massachusetts to Concord, New Hampshire in 1829, which is recorded with philosophical diversions in his Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, published in 1849. He stopped at Concord again in 1858 after a frigid climb through the snow to the top of Mt. Washington.

Note

This article was originally published in the Longyear Quarterly News, Autumn 1975.