In her Message to The Mother Church for 1901 (pp. 31-32), Mary Baker Eddy praises with warm affection the “grand old divines” who taught her as a young girl growing up in New Hampshire. Concluding her tribute, she writes: “I believe, if those venerable Christians were here to-day, their sanctified souls would take in the spirit and understanding of Christian Science through the flood-gates of Love;…”

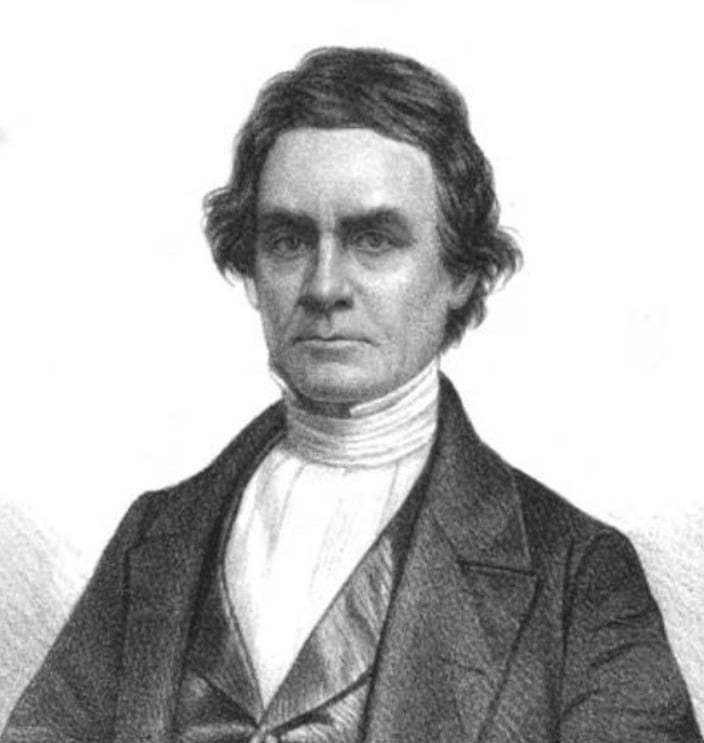

Among the six distinguished clergymen Mrs. Eddy mentions by name is Rev. Nathaniel Bouton, D.D., pastor of First Congregational Church in Concord, New Hampshire, from 1825 through 1867. Mrs. Eddy’s parents, Mark and Abigail Baker, joined Bouton’s church in 1831, and the popular young minister, who baptized Mary Baker as a small child, was a frequent guest in their home in Bow. This article examines the life and character of the Rev. Dr. Bouton, who contributed to the early religious education of the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science.

In the spring of 1813, a boy — the youngest and brightest of his parents’ fourteen children — rode fifteen miles on horseback from Norwalk to Bridgeport, Connecticut, in response to the following newspaper advertisement: “Wanted at this office, an apprentice to learn the printing business.” His earnestness and eagerness to learn won him the position, which he felt would provide the opportunity to read, as his family owned few books.

He was to remain for two years, until, at the age of sixteen, “the good Providence and Spirit of God, soon gave a new impulse and direction to my mind.”1

Young Nathaniel Bouton had caught the spirit of excitement and new possibilities of his time, and with little ceremony had ventured beyond the unyielding stone walls of his father’s farm to explore larger and more fruitful fields.

The year Nathaniel began his apprenticeship, the premier performance of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony was given in Vienna, and the British public first read Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Closer to home, the War of 1812 continued to hold the concerned attention of Americans, as their largely untried naval forces strove to prove their mettle in a second great struggle with Great Britain. During the previous year, the venerable patriarchs John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, whom age and time had softened, made amends after years of estrangement, finding that their love of the country they helped found was stronger than divergent partisan opinions.

In religion, the ubiquitous white spire of the Congregational Church dominated the New England landscape, although a few modest challengers, the foremost of which was the Baptist Church, had gained a foothold in the region. Theological liberalism was beginning to emerge as well, corning to a head in the so-called “Unitarian Controversy” of 1815. Led by William Ellery Channing, this revolt against the strictures of Congregationalism would jostle the foundations of religious beliefs that had held up for some 200 years.

Congregationalism itself, perhaps as a response to the loss of many of its members to Unitarianism, would by mid-century see sweeping changes, mitigating the severity of orthodoxy to such a degree as to disturb the church’s Calvinist roots, and eventually eradicate them. Henry Ward Beecher, born in 1813, would become one of the best known exponents of this liberalization of the church, whose sterner doctrines had caused him such difficulty as a young man. Yet in the ordered rural life of a Connecticut village in the early decades of the nineteenth century, such impending storms were no threat to the sturdy meeting-house structure.

The Congregational Church in Norwalk left deep impressions on the character of Nathaniel. As a small child he had been well schooled in the Ten Commandments, the Westminster Catechism, and the Lord’s Prayer, the last of which he repeated each night before going to bed. During his youth, religious revivals were sometimes held which on at least one occasion moved him to tears. Possessed of a “tender” conscience, he offered himself to God’s service at the age of sixteen partly as a result of being deeply affected by his father’s admonition: “My son, you are now old enough to be a Christian.”

Much soul-searching and deep study of the Bible followed. Self-distrust plagued him, as well as “a sense of total unworthiness and sinfulness before God.”2 Emerging from such brooding introspection, however, he became animated by the prospect of preparing for a career that would give his life profound meaning. As he later wrote: “My mind became aglow with religious thoughts and feelings; new desires and aspirations were awakened. I began to think of a college — could I ever reach it? Obstacles presented themselves which seemed insuperable. I was an indentured apprentice, bound to serve four years more. I had no means by purchase to take up my indentures, or, if I could, to prepare myself for a college. Yet the idea of an education grew upon me; I desired it, that I might be suitably qualified to preach the Gospel. That became my absorbing thought.”3

Through the sale of two acres of land by his father and money raised by neighbors and friends, Nathaniel was released from his indentures and began preparatory study for Yale. Ministers from his hometown of Norwalk and the neighboring towns of New Canaan and Wilton offered him tuition-free education at local academies, as well as private tutoring, and provided the means for him to attend Yale. His gratitude for all that these gentlemen had done for him was such that he felt obligated to repay them — not monetarily, but in spreading the gospel in the towns where they resided. Thus, while a student at Yale, he spent his vacations in meetings with young people that awakened their interest in religion.

Upon graduating, Bouton pursued his studies at Andover Theological Seminary, where he was introduced to teachings that occasionally seemed to conflict with the doctrines of the Westminster Catechism he had learned by heart as a child. Instruction at Andover on “the freedom of the will” was not easily reconciled with Calvinist dogma that rigidly held to the belief in an inscrutable Providence who foreordained either the salvation or damnation of every sinning mortal, taking no account of the individual’s sincere efforts toward reformation.

Bouton was troubled, lest by embracing the concept of man as a free moral agent, he should appear to depart from the religion of his youth. He describes in his autobiography how he came to terms with the difficulty: “While I fully believed in man’s dependence for all good on the ‘Grace of God,’ I learned that the grace became effectual by the willing reception of it in a free agent. Consequently, in all my preaching, I have insisted strenuously on duty and obligation, admitting no excuse for sin or disobedience in any form, but at the same time teaching that Divine Grace was assured to all who sought it. In short, I embraced heartily the system of theology as taught at Andover….”4

(One of his more thoughtful future parishioners, the young Mary Baker, was to find herself troubled as well by the severity of Calvinism, specifically the doctrine of predestination.)5

Pestered by the same sensitive conscience that disturbed the serenity of his boyhood, Bouton drew up the following set of resolutions during his second term at the seminary:

“1. Resolved, That I will not dispute with any of my brethren, but whenever a discussion is required, I will advance my opinion with reasons for it, and then dismiss the subject.

“2. I will not contradict, but carefully guard against positiveness of opinion, always remembering that I am very fallible, and liable to be mistaken in the plainest and most simple matters.

“3. In intercourse with my brethren I will aim to treat them according to the Spirit of the Apostle’s direction: ‘Let each esteem others better than himself.’

“4. I will guard against hasty, uncharitable, and censorious remarks.”6

Fifty years later he confessed that he was “not yet cured” of his argumentative tendency, a fault well hidden from all who knew him, including his family.

Bouton’s strong belief in accountability for one’s actions is underscored in a speech entitled, “The progressive diffusion of moral influence,” delivered before a debate club at Andover. He writes: “Who estimates with sufficient thoughtfulness the consequences of single actions? Who of thoughts and emotions? Who realizes that he cannot move without touching chords that may vibrate round the globe, and through Eternity?” Amplifying his theme, the young divinity student observes in his own time the far-reaching effects of such morally and spiritually disciplined thinking: “In the united and extensive operations of benevolence, that distinguish the present period, we see a full developement of the principle which the scriptures assure us shall work the regeneration of the world.”7

Graduating from Andover in September 1824, Bouton toyed briefly with the idea of missionary work in Syria and Palestine, or in “the great West,” which interested a number of his classmates. But as he had always wished to be a settled pastor, he decided after “careful and prayerful consideration” to accept an invitation from the Congregational Church in Concord, New Hampshire, to preach at that church for seven weeks as a ministerial candidate.

He made his debut with a sermon based on the text, “But one thing is needful: and Mary hath chosen that good part, which shall not be taken away from her” (Luke 10:42). Confronting him as he mounted the pulpit that first Sunday morning was his own sense of inadequacy, exacerbated by the awareness that the congregation whose eyes were fixed on him was a large, distinguished, and critical one. An additional vexation was the extreme reserve of the parishioners, who, during the entire seven weeks of his candidateship, never expressed appreciation for any of his sermons.

On January 1, 1825 Bouton received word that the church voted unanimously that he be called to serve as their pastor. He accepted, and on March 23, 1825 Bouton was ordained. Among the eleven ministers in attendance were Rev. Abraham Burnham of Pembroke, well known and respected by Mark Baker and his family in neighboring Bow, and Enoch Corser, who in 1838 would admit the 17-year-old Mary Baker as a member of the Congregational Church in Sanbornton Bridge (today, Tilton). The Bakers attended Rev. Bouton’s church from 1829, after the church in Bow disbanded, until 1835, when the family moved to Sanbornton Bridge.

Rev. Bouton’s preaching was doctrinal, as the times demanded, and yet was tempered with warmth and humanity. This benign side of the clergyman’s nature doused some of hellfire’s most searing flames, as his son recalls in his depiction of a typical Bouton sermon at Old North Congregational Church: “The pastor manages his voice skilfully. It is loud and emphatic in the condemnation of sin. But it sinks to a whisper when he refers to ‘Sheol’ by the equivalent of the old version. He does not conceal the terrors of the law, but he never shakes them like a stick at his congregation. He appeals to reason and not to fear, and to the heart more than to the conscience. And he does all this in plain English which everybody understands.”8

It is not surprising that a minister characterized by his son as “liberal in his Orthodoxy” would find ways to reach out to those whose needs had rarely been addressed by the church. It was his heartfelt concern for each individual, as much as his superior abilities, that drew crowds (approximately 750 women, men, and children every Sunday) from long distances to hear him preach. Particularly fond of young people, he formed a Bible class for young women that proved highly successful. Starting with the Gospel according to Matthew, he required the students to study each lesson in preparation for a thorough discussion of its meaning. They were encouraged to ask as well as answer questions, evidently a new concept to women at that time.

Women’s voices could be heard as well at Bouton’s “family conferences,” held once a week. Each person attending brought a question in writing which would be read by the pastor and discussed by those present. First, the “brethren” would be given an opportunity to respond; then the ladies were invited to share their comments. In 1831, when it was still widely held that women, like children, should be seen and not heard, Bouton’s modest but significant reforms must have come as a breath of fresh air to female parishioners unused to expressing their spiritual insights — except in prayer.

According to his son, however, Bouton was not unlike most men of his day in the raising of his family of thirteen children. In a eulogy to a “pious” wife of a fellow minister, he conforms to the patriarchal stereotype, extolling women who obey the Scriptural directive regarding obedience to husbands. And yet his recognition of womanhood’s integral spiritual role throughout the Scriptures, and particularly in Jesus’ ministry, bespeaks a deeper understanding. He writes: “It was a woman…to whom Jesus said, Great is thy faith; be it unto thee even as thou wilt;… When all the disciples of Jesus had forsaken him and fled, then daughters of Jerusalem followed…. It was woman’s love, stronger than death, which clung last to the cross;…and woman’s voice first gladly announced his resurrection.”9

The dedicated and tireless Rev. Bouton visited each family in his large parish at least once a year, usually on horseback, attending especially to the sick and elderly, with whom he prayed. He also lectured once a week in schoolhouses in outlying areas, and held Monday evening meetings for those who simply wished to converse freely with the pastor on religious subjects as a preliminary to church membership. “Sabbath schools” were so increased that by 1832 sixteen schools were conducted for 925 students.

Bouton’s preparation of sermons was methodical and thorough. He always wrote each one out in full, leaving extemporaneous preaching for less formal occasions. The text would be studied first in Greek or Hebrew; then the theme would be thoroughly pondered and researched until it became lucid. Not until then would he begin writing, very quickly without interruption, until the 35-minute sermon was completed. Bouton states: “I can testify that sermons that have cost me most study and labor in preparation have been also best received and appreciated. The people well know when they are fed. My habit was to devote an hour Saturday evening to a review and correction of what I had written, and implore upon it the blessing of God’s Holy Spirit, again, before entering the pulpit, and again, after preaching.”10

In a sermon that includes a brief history of First Congregational Church in Concord, Bouton emphasizes that its early members were “orthodox” and calls attention to the Greek derivation of the term, meaning “right doctrine.” Reaffirming the church’s commitment to orthodoxy, he adds: “Though some changes have taken place, yet it is matter of devout thanksgiving to God, that this Church, planted a hundred years ago in the wilderness, is now both in doctrine and discipline what it was then. Far be the day when it shall be moved from its foundation!”11

As if in sympathetic response to Bouton’s fervid desire to preserve the integrity of the Congregational Church, Mary Baker Eddy would write three-quarters of a century later of her love for the church of her youth, indicating that it and the “new-old” church that she established have the same foundations, “even Christ, Truth, as the chief corner-stone.”12

The years of Bouton’s ministry, 1825-1867, were punctuated by a number of notable events in Concord. Within the decade following a much-heralded visit by the Marquis de Lafayette (during the first months of Bouton’s pastorate), President Andrew Jackson attended a service at Old North. On June 28, 1833 his party rode up the river road in Bow (by the Bakers’ farm) and stopped at the Concord line, where the President emerged from his carriage, mounted a white horse and dramatically rode into town to the cheers and waving handkerchiefs of some 10,000 people who crowded into Concord for a glimpse of “Old Hickory.” A few years later an angry town mob threatened to tar and feather the Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier, an ardent abolitionist, who had been scheduled to speak at an antislavery rally. And in 1845 the issue of slavery was again hotly contested during a famous debate in Bouton’s church between Franklin Pierce and John P. Hale, an abolitionist member of the U.S. Senate.

Bouton maintained that he never preached a sermon in which his personal political views were aired. He was outspoken, however, when the governing principles of his country were under attack, either politically or morally, and his strength of character in this regard was particularly evident in his active support of the temperance movement.

His self-control was severely taxed during an incident that could have resulted in bodily injury. In 1836, Dr. George B. Cheever, the author of a scathing expose of the evils of alcohol, was invited to give a lecture at Old North. The “rum interest” rioted and attempted to batter down the door of Bouton’s home, where Dr. Cheever was staying. Failing in the attempt, they burned Cheever in effigy in the State House yard. Had the ruffians broken in, speculated Bouton’s son, his father would have “risked his own life in a desperate resistance. That meek and polite man would have received his assailants with the kitchen poker.”13 Happily, circumstances precluded the necessity for such uncharacteristically violent behavior.

Bouton resigned as pastor in the forty-second year of his ministry, feeling somewhat out of step with the younger generation and sensitive to indications that a change was desired. He was then appointed state historian, a position well suited to one whose love of the religious legacy handed down by Puritan settlers two centuries earlier had been the motive-power of his life. His History of Concord, on which he had worked painstakingly during such spare time as his ministry would allow, had been published in 1856, a natural outgrowth of his work as president of the New Hampshire Historical Society during the 1840s. After his retirement, he continued to serve as a trustee of Dartmouth College, having been appointed in 1840. (Dartmouth had granted Bouton the honorary degree of Doctor of Divinity in 1851.) He passed on in 1878, just after the completion of his autobiography.

The following passages from a sermon entitled “Private prayer” reflect Bouton’s uncompromising attitude toward evil, as well as his tender concern for the individual: “Beloved brethren, do you pray in your closets?… Do you enjoy the devotions of the closet; find nearness to God there, and experience in your soul that peace and joy, that resignation to the divine will, love to mankind and foretaste of heavenly bliss, which other Christians have experienced, and which are a part of the reward promised to secret prayer? If, brethren, you cannot answer these questions in the affirmative, what is the reason?… Examine yourselves…. If, on examination, conscience accuses you of living in any sort of sin, then you may know the true reason why your closet devotions are barren and joyless….

“Do any of you, who are members of this church, wholly neglect private prayer?… What, then, is your experience? What progress do you make in spiritual religion?… I would also seriously and affectionately ask you, Why you do not pray in secret?…

“Call then upon [God] now. He bends from his mercy-seat to hear and save! Let the prayer of thy heart, offered in silence here, be repeated, and urged with fresh importunity in thy closet at home…. Daily, to the end of life, ‘enter into thy closet, and pray to thy Father who seeth in secret, and he will reward thee openly.'”14

It is likely that the twelve-year-old Mary Baker heard Bouton speak these words from his pulpit at Old North Church in 1833. Could it have been such sermons that prompted her in later years to write of Dr. Bouton: “The religion that he taught and lived, I love and honor. It was the vestibule of Christian Science.”15