Many interesting discoveries came to light from researching and writing about the achievements and life stories of four early workers — Emma and Abigail Dyer Thompson, Janette Weller, and Annie M. Knott — who helped Mary Baker Eddy establish her religion and Church. Read their stories in full in Paths of Pioneer Christian Scientists.

Like many of the early Christian Scientists, Emma Thompson, Janette Weller, and Annie Knott each came to this new religion in great need of healing.

Annie M. Knott, after hearing the cries of her young son Frank, walked into the kitchen and discovered her little boy had drunk the contents of a bottle of carbolic acid. Doctors called to the emergency told her there was nothing they could do at that stage of poisoning. As a last resort, Mrs. Knott, who had been reading a copy of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy, sought help from some Christian Scientists she knew. Christian Science treatment was given and by the next day the boy was completely healed. She would call the event “the entrance into Life.”1

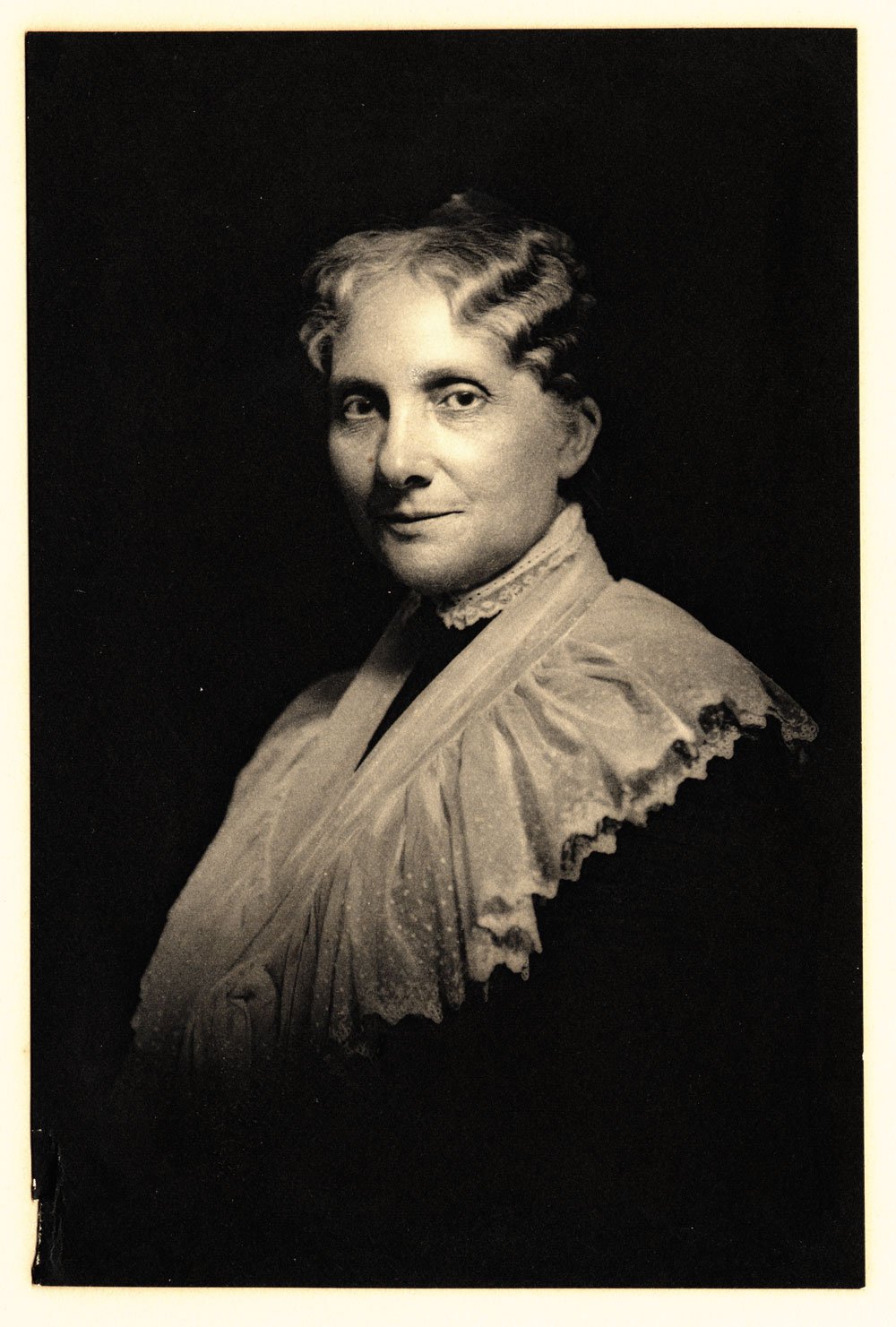

Emma Thompson had suffered from a painful case of neuralgia of the head since childhood — a condition that, as her daughter Abigail wrote, made her mother “nearly frantic”2 at times. Now in her forties, she, too, began reading and studying a copy of Science and Health and was completely healed after decades of slavery to this ailment.

Janette Weller had been struggling for nearly twenty years with consumption (tuberculosis), when she got a copy of Science and Health, studied it, and she, too, was completely healed The healing left her, she said, “free as a bird.”3

Each of these healings took place in 1884. Each healing resulted from being introduced, at a critical time in her life, to Science and Health. And, interestingly, after her healing, each pioneer — Mrs. Knott in Chicago, Mrs. Thompson in Minneapolis, Mrs. Weller in Littleton, New Hampshire — pivoted 180 degrees onto a new life path.

Shortly after her healing, each began to help and heal others solely from the understanding she was gaining from her own study of Science and Health. Each would attend class with Mary Baker Eddy, enter the full-time work as a Christian Science practitioner, and plant the seed of truth in her respective city.

Yet, despite this similar set of circumstances, all three of these pioneer Christian Scientists have unique stories of what took place as they went about this work — the challenges met and surmounted, the resistance overcome, the doubts destroyed, and the many victories and triumphs that resulted from holding steadfastly to the truth they had been shown by Mrs. Eddy in Christian Science.

This autumn Longyear Museum Press is publishing a book containing the stories of four early workers — Emma and Abigail Dyer Thompson, Janette Weller, and Annie M. Knott. Titled Paths of Pioneer Christian Scientists, this work examines these four lives from the vantage point of what they accomplished and how they accomplished it: What were some of the unique ways they went about establishing Christian Science? What qualities do we see these early workers expressing? With this as the focus, their stories are not only interesting, but highly instructive and deeply inspiring.

So many interesting discoveries resulted from researching and writing these profiles.

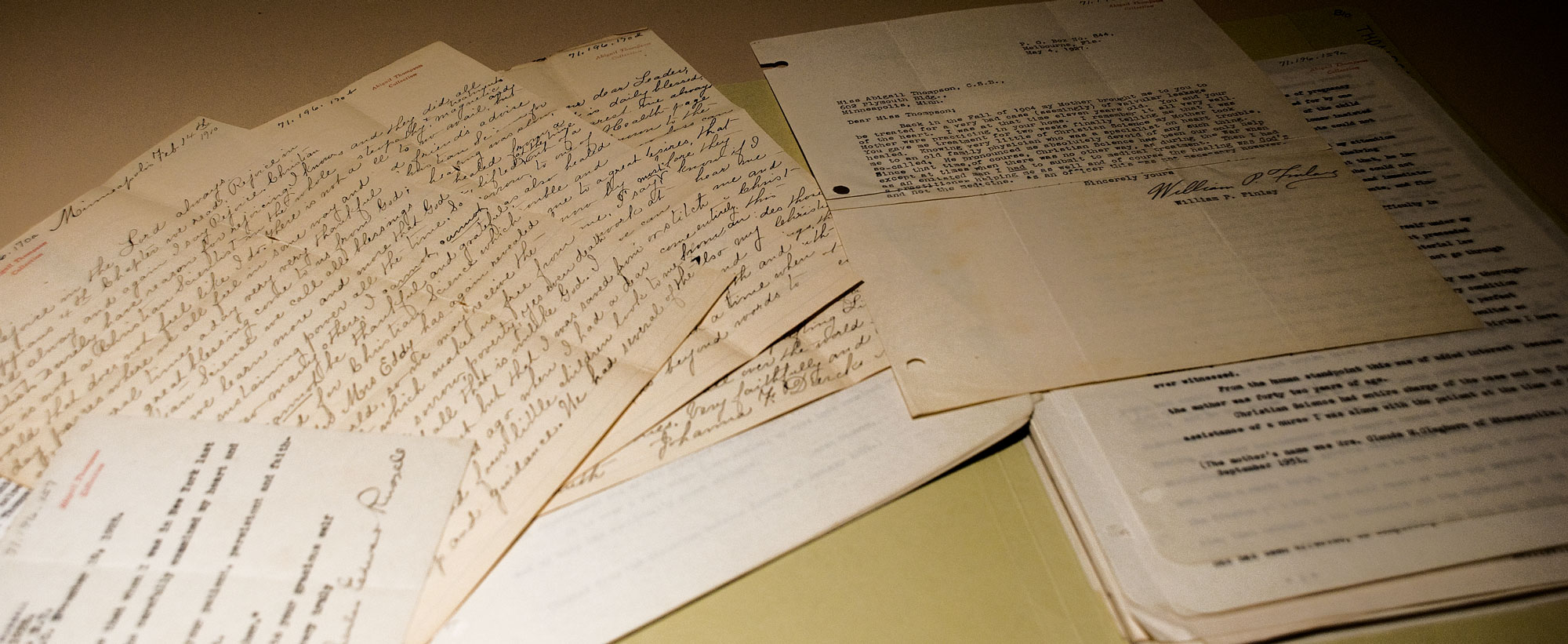

I recall a winter night while living in Longyear Museum’s Mary Baker Eddy Historic House in Rumney, New Hampshire, where I was Resident Overseer. I was reading through the reminiscence of Minneapolis Christian Science practitioner Abigail Dyer Thompson, and then the correspondence that travelled back and forth between her mother and Mary Baker Eddy. I was trying to get a sense of the underlying story and so had spread photocopies of these documents across my living room floor for examination.

I suddenly noticed what appeared to be Mary Baker Eddy’s handwriting in an unexpected place — on the envelope of a letter from Emma Thompson. I had been tracing an 1887 reference to a case taken up by Mrs. Thompson. Her patient was a woman named Lissette Getz, whom Mrs. Thompson had earlier healed of invalidism from a knee fracture. Mrs. Getz later suffered a mental breakdown, and was committed to an insane asylum. Mrs. Thompson went to visit her patient at the asylum but was turned away and not allowed to see her.

Mrs. Thompson came home and wrote Mrs. Eddy of the particulars of the case, telling how her patient’s family claimed that the mental derangement had resulted from studying Science and Health.

Mrs. Eddy’s return letter instructed Mrs. Thompson how to handle the situation:

The woman was not hurt reading truth — if error says that, it lies, and you know it, and you must establish the truth in your own and your patient’s mind. You know there is but one Mind and there is no other to be deranged. There is no deranged mind— know this and make it appear.4

Mrs. Eddy’s instruction brought exactly what was needed, and after it arrived, Mrs. Getz was healed. Mrs. Thompson went down and helped bring her patient out of the institution. Mrs. Thompson later wrote a letter to Mrs. Eddy, telling her about the healing. It was on the envelope of this letter that Mrs. Eddy had written the note I saw when I began my research. Just to the left of the post office date stamped on the envelope, are the words in Mrs. Eddy’s handwriting: “Certif[ication] of my healing.”5 This discovery of Mrs. Eddy’s writing on the front of the envelope unfroze a moment of time from a century and a quarter ago.

Such are the rewards of research, study, reading and rereading historic documents — every so often one is able to coax from evidence its secrets. From that time on, I realized the operative words for this project were stay alert. We were going to cover some very interesting terrain.

Indeed, writing Paths of Pioneer Christian Scientists was a little like hiking deep into a California redwoods forest. The further in one travels, the more unexpected the landscape, and the more interesting the discoveries. One thing had already proven itself true: research, with its somewhat lack-luster reputation, had been transformed into a powerful telescope of discovery.

Many such discoveries awaited.

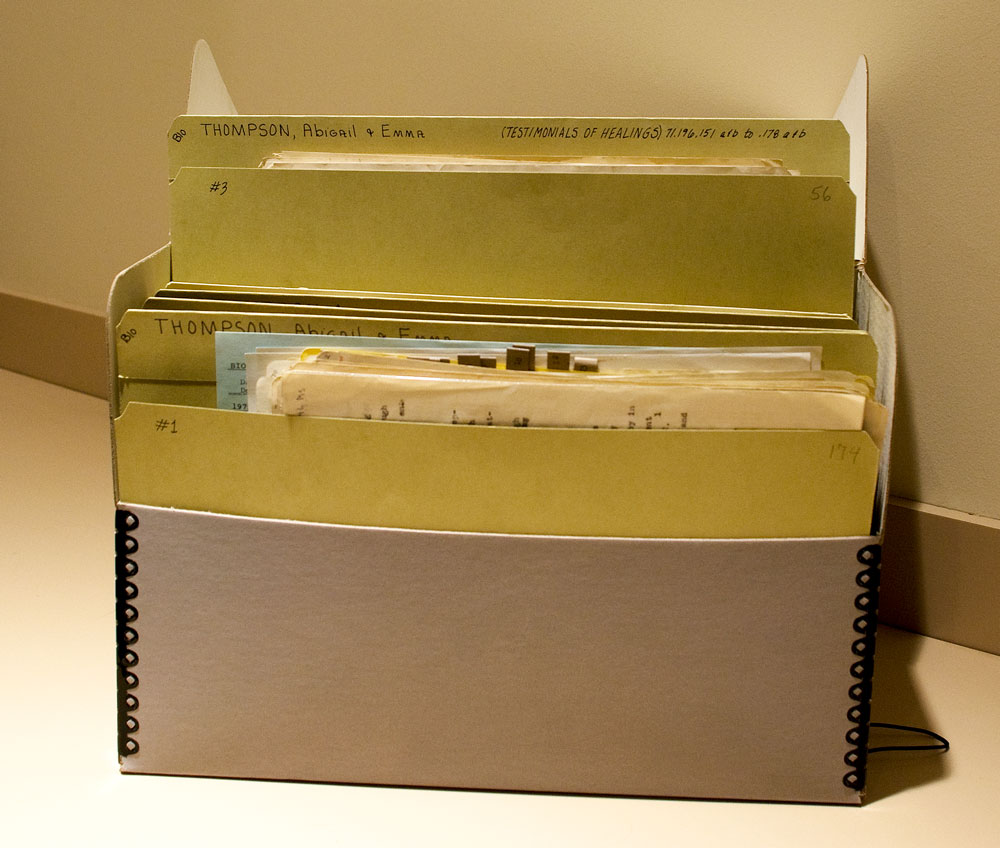

I recall, early on in the research process, retrieving a documents box from Longyear’s vault containing files on Emma Thompson and her daughter Abigail. As I was looking through the various folders, my eye fell on one folder marked “Healings.” At the time, this did not strike me as an unusual discovery, given that both Thompsons were prominent Minneapolis practitioners who left behind remarkable records of healing.

It was in the light of Abigail Dyer Thompson’s account in her reminiscence of a visit with Mrs. Eddy in New Hampshire sometime in the 1890s, that I realized the significance of this file of healings that sat in Longyear’s vault.

During a visit, the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science once asked the teenaged Abigail whether she was keeping a record of her healings. Abigail replied that while she was grateful for each healing, it had not occurred to her to keep such a record.

Mrs. Eddy told her student, “You should, dear, be faithful in keeping an exact record of your demonstrations, for you never know when they might prove valuable to the Cause in meeting attacks on Christian Science.”6

Mrs. Eddy went on to tell Abigail that many early healings from her own work — “much of my best healing work,” she said — were never recorded. Consequently, Abigail and her mother kept a record of their healing work. Mrs. Eddy’s request almost certainly resulted in this file of healings in the Longyear vault. Thanks to their obedience to Mrs. Eddy’s instruction, the pioneer articles on Emma and Abigail Thompson are rich with examples of their healing work — works that were known throughout Minneapolis and that resulted in a multiplication of branch churches in that city, as healed patients took up the study of Christian Science and became church members.

One of the most interesting facets of studying these four women was seeing their lives emerge into a sense of dominion. At times, the process resembled a kind of nature documentary time-lapse photography sequence, in which one watches, in a few seconds of film, some colorful flower quickly open and unfold.

One example of this can be seen by looking at excerpts from some of Emma Thompson’s letters to Mary Baker Eddy over a six-year period. In these sentences, extracted from the letters, Mrs. Thompson comments about her life experience and, in the process, leaves behind the bread crumbs that enable a twenty-first-century reader to see her path and how she became such a remarkable practitioner.

Here are excerpts taken from a few of her letters to Mrs. Eddy between 1886 and 1892:

I have no time from early morning till late at night.7

I am now working fifteen hours per day not one moment to spare.8

Since I left Boston doubts — fears have vanished like dew before the sun. Yes, — God is all to me. He leadeth me.9

Now in my fourth year sitting from early morn till late at night have arrived to the place I wanted namely the best Healer, not for fame, only to show the Truth — as Mrs. Eddy teaches was the truth. And now my work must talk for me…10

Since my return [from visiting you] one year ago this month I have gained more understanding than all the seven years of work, seven this fall.11

The interest that is taken in Science with us is certainly wonderful. I have never seen anything like it.12

From these excerpts we see something of the dominion she was clearly gaining, and the resulting interest being shown in Christian Science in that city.

Indeed, Mrs. Eddy herself commented on Emma Thompson’s devotion to the goal of becoming a Christian Science practitioner, telling Emma’s daughter, Abigail, during one of her visits to Pleasant View:

As a rule my students have wanted to heal, and preach, and teach. … In contrast to this, your mother has been satisfied to do just this one thing — to heal the sick — and she has been humble enough, and selfless enough to continue steadfast in the healing work until she has given to the world an exact proof of the way Christian Science should be demonstrated.13

Other qualities common to this group of pioneers include remarkable honesty and forthrightness with Mrs. Eddy — even about their weaknesses. In Science and Health, Mrs. Eddy writes of the human mind’s disinclination to self-correction,14 but so great was their desire for spiritual growth, that this group of women submitted themselves to self-discipline and correction.

“I shall expect you to chide me and censor me as you see fit,” Emma Thompson wrote her teacher on October 5, 1886, “and any advice will be most cordially received now. I have many faults, and I want you to watch me closely.”15

Janette Weller, in a May 3, 1895, letter to Mrs. Eddy, put it a little more succinctly: “If I need to be whipped, I want to be.”16

Annie Knott greatly valued and took to heart a severe lesson she had learned from one of Mrs. Eddy’s rebukes. Mrs. Knott had just completed the February 1887 Normal class in Boston and returned home to Detroit to her family and busy healing practice. A few weeks later, a letter arrived from MRs. Eddy, requesting Mrs. Knott to return to Boston in a few weeks’ time to attend the April 13 meeting of the students of the Nation Christian Scientist Association.

Mrs. Knott sent word she could not attend the meeting. Not only did her busy practice demand her presence at home, she felt, but traveling to Boston would also mean she would have to ask her husband — the man who had only recently walked out on her — for money for the trip.

Mrs. Eddy’s return letter arrived a few days later by American Express, just as Mrs. Knott was about to give a treatment to a patient. Perhaps Mrs. Knott detected the smell of smoke coming from Mrs. Eddy’s words: “I have gotten up this N.C.S.A. for you and the life of the Cause,” Mrs. Eddy wrote. “I have something important to say to you, a message from God. Will you not meet this one request of your teacher and let nothing hinder it? If you do not I shall never make another to you and give up the struggle.”17

Mrs. Knott immediately reversed course, cut a hasty path to the Western Union office and sent Mrs. Eddy word that she would indeed attend. The episode had a humbling effect on Mrs. Knott, teaching her the need for and power of obedience that would inform so many of her future decisions.

Many years later, Mrs. Knott eloquently explored the subject of obedience and the spiritual possibilities it enables: “[E]very step taken in obedience to divine law means far more than we are able to see at the time, or, perhaps, for long years there-after.”18

There are many lessons these pioneers learned as they went about their work. These stories show, again and again, how they came to realize that the spiritual gifts they had been given were not intended just for themselves, but were meant to be handed out to others.

The efforts of the pioneer Christian Scientists to help and heal others make not only for some very interesting stories, they also form some of the foundation blocks of Christian Science history.