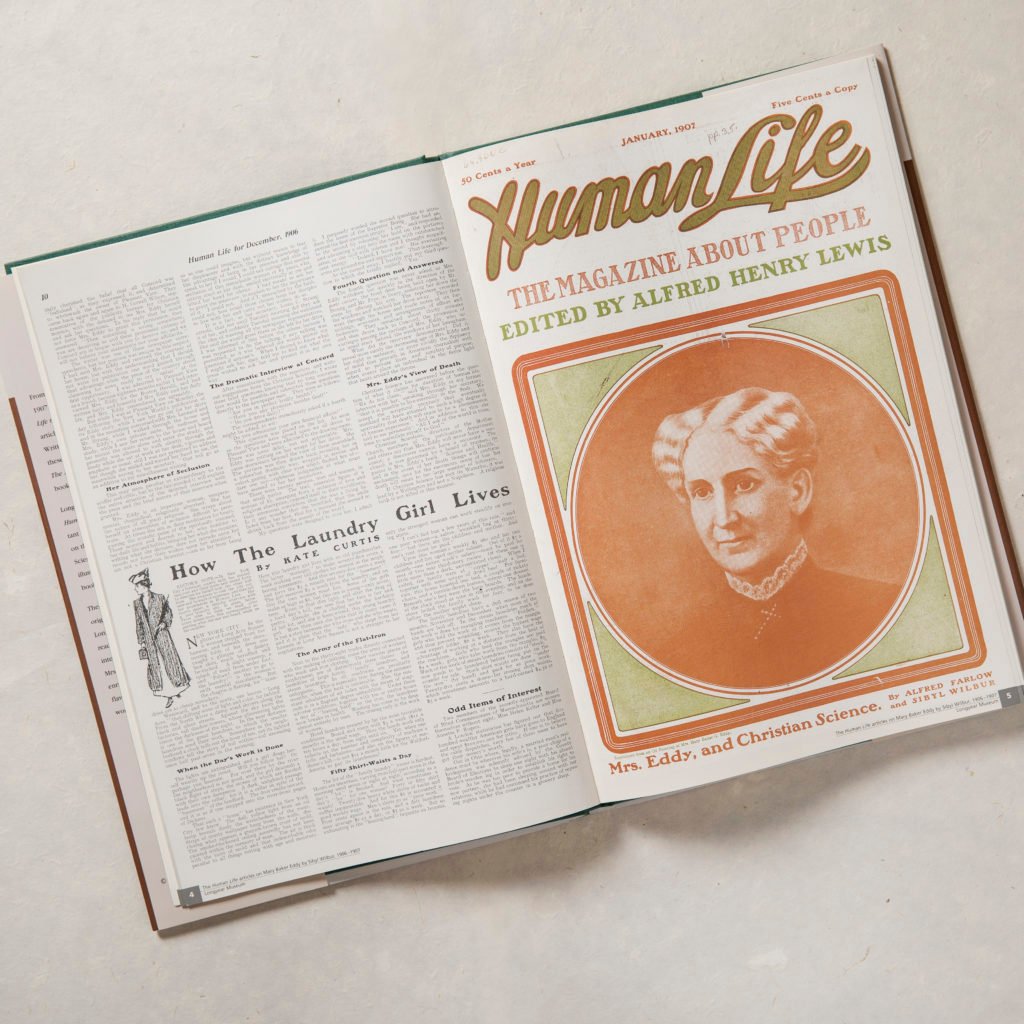

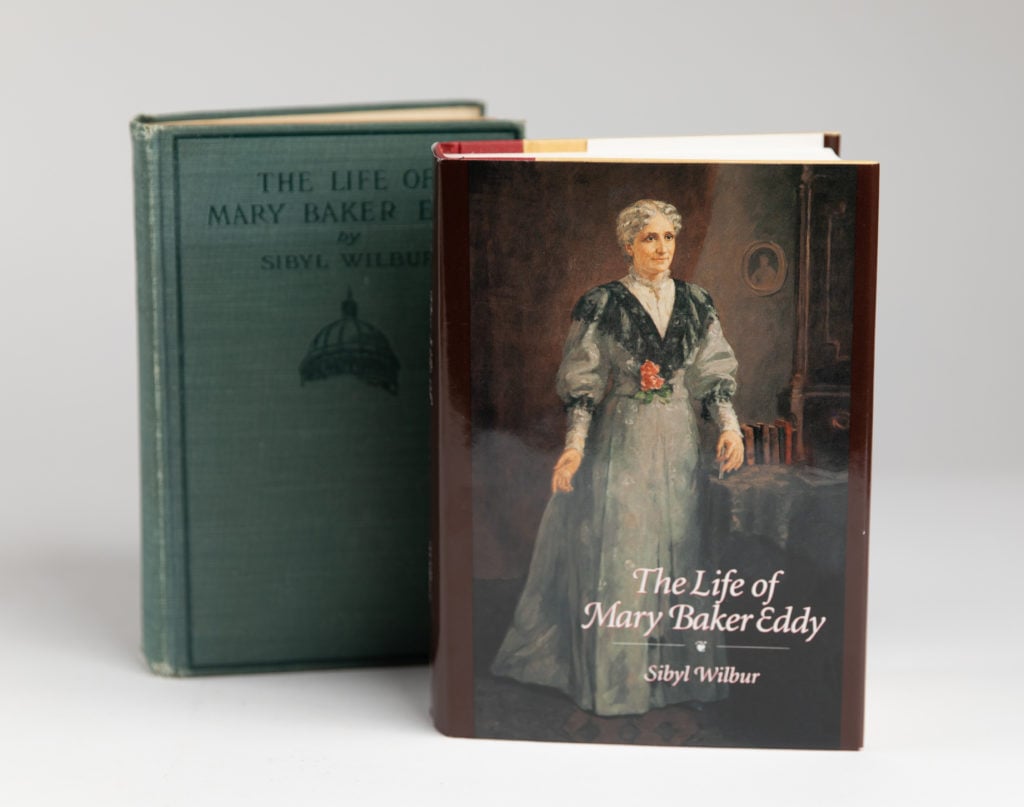

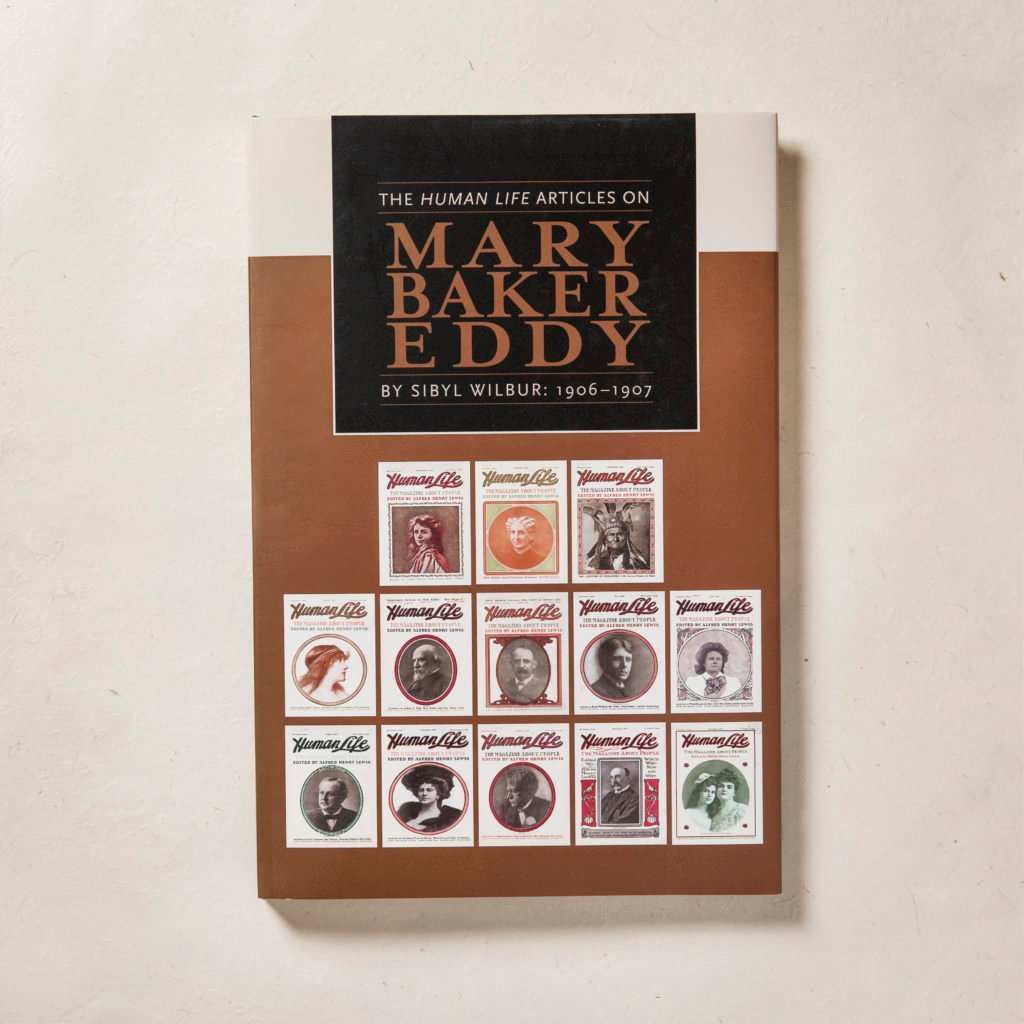

From December 1906 through December 1907, the Boston-based magazine Human Life ran a ground-breaking series of articles on the life of Mary Baker Eddy. Written by noted journalist Sibyl Wilbur, these articles formed the basis of her book The Life of Mary Baker Eddy – the first book-length biography of Mrs. Eddy.

Miss Wilbur’s articles were published in thirteen installments, during a period of intense public scrutiny of the life of Mary Baker Eddy, scrutiny that was filtered through lenses ranging from the outright hostile to the laudatory.

In 2000, these Human Life articles on Mrs. Eddy were reproduced by Longyear Museum Press in the hopes of making them more readily available to researchers and readers, as well as to those who find enrichment and enjoyment in getting a flavor of the times in which Sibyl Wilbur’s work appeared. The book’s introduction, by Longyear’s former Curator·Director Stephen Howard, explains the significance of the articles and offers historical context.

It is not altogether easy today to capture the depth of feeling in 1907 that surrounded articles on the life of Mary Baker Eddy. That year, detailed information about her history was available to the public for the first time. Two serialized magazine accounts, very different in their interpretations, offered probing scrutiny of her past.

Sibyl Wilbur’s thirteen articles appeared in Human Life from December 1906 through December 1907. Running concurrently, McClure’s Magazine was treating the public to Georgine Milmine’s lurid and sensational account of Mrs. Eddy’s life, largely ghost-written by Willa Cather.1

While this battle over Mrs. Eddy’s history occupied these magazines, intense interest in her present occupied newspapers. A month before the Wilbur series began, the New York World headlined that Mrs. Eddy was dying and was under the control of her household. With financial backing from the World, the “Next Friends’” suit was launched on March first. Although ostensibly on Mrs. Eddy’s behalf, it was in fact intended to secure control of her property for close relatives, by proving her incompetent. The suit dragged on during the spring and summer, providing rich fare for the press. The suit collapsed on August 21, when Mrs. Eddy’s mental competency and physical health were unassailably established by a court interview. Mrs. Eddy had won a moral, but not a legal, victory.2

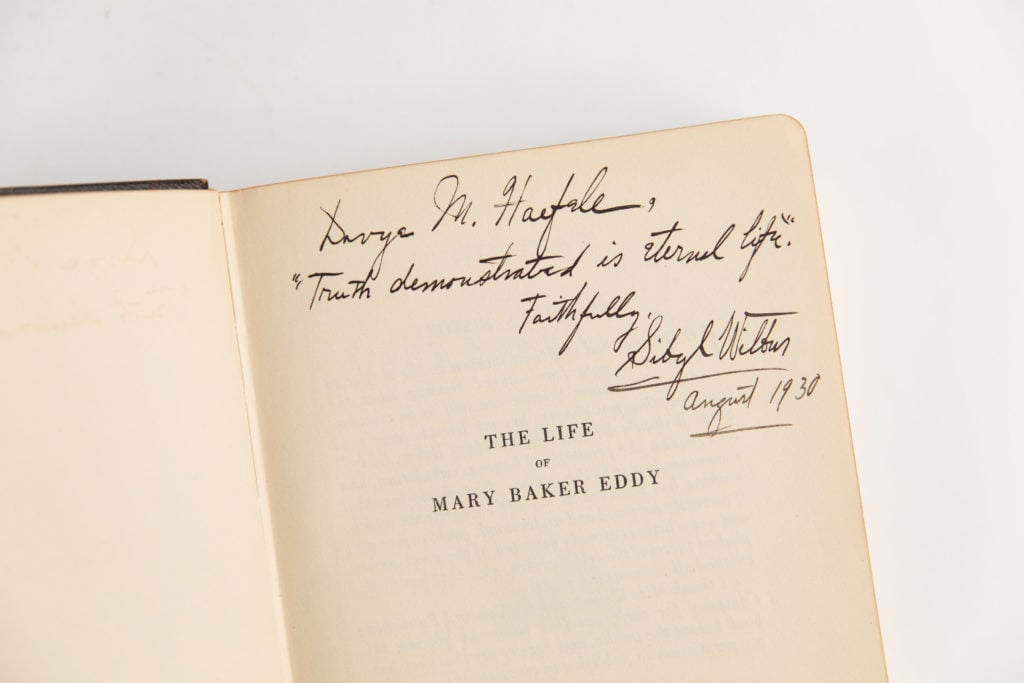

While the suit was still playing itself out, the two magazine series in McClure’s and Human Life offered the public two strikingly different portraits of Mrs. Eddy. Each series was later revised and issued in book form. Two strikingly different biographies: the first, by Sibyl Wilbur, was entitled The Life of Mary Baker Eddy and was published in August 1908; the second, The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science, was published in 1909 and was credited to Georgine Milmine, though it was mostly written by Willa Cather.

Each biography was more extreme than its original magazine series. Demonstrably inaccurate in many respects, the Milmine/Cather biography remained for many years the unquestioned source of information about Mary Baker Eddy, while the adulatory style of Sibyl Wilbur’s biography made it easy game to dismiss as mere hagiography.

Readers of the Wilbur biography often find, however, a freshness in her Human Life articles. The articles are an important source of information, and they themselves constitute documents in the history of biography on the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science. The series represented the work of a journalist who had spent months in investigation and research, interviewing people who had known Mrs. Eddy decades earlier, and obtaining statements and gathering information that otherwise might have been lost. She crisscrossed New England, tracking down leads and getting to the bottom of legends.3

Today’s reader will not, of course, find in Sibyl Wilbur’s series the “last word” on biography about Mary Baker Eddy. The series belongs rather to the inception of biography on this religious leader. Nearly a century of research and documentation unavailable to Sibyl Wilbur (and to Willa Cather, for that matter) has accumulated in the intervening years and adds perspective necessary to a balanced assessment of Mrs. Eddy’s life.

Sibyl Wilbur’s original articles have been photographically reproduced by Longyear, making this ground-breaking series of articles more readily available. Recognizing that Miss Wilbur wrote during a period of caustic attacks on Mrs. Eddy can assist modern readers to appreciate more the author’s dry, sometimes sarcastic humor, and to understand the context of her sympathetic portrayal of Mrs. Eddy.

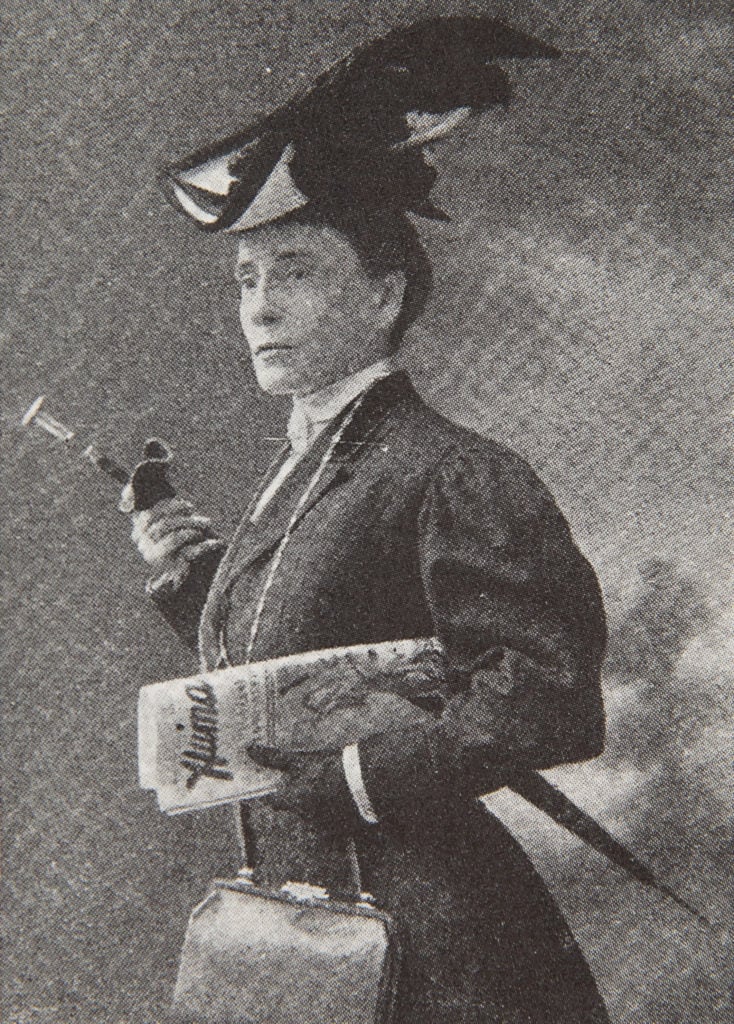

While the articles present valuable first-hand interviews, they are not exempt from the sort of error that may occur in any biography. For instance, a photograph caption states that Mrs. Eddy wrote Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures in the attic room of her house on Broad Street in Lynn. The fact is that she wrote about a dozen pages there and corrected proof pages for the first edition. But a mistake like this does not detract from Miss Wilbur’s later firsthand observation of how uncomfortable living in such an attic room would be, experience she herself had gained while living in an attic room when she reported on the working conditions of Lynn shoemakers.

When the Human Life series concluded in December 1907, Miss Wilbur was already at work on her biography of Mrs. Eddy. The road to publication proved bumpy. The book was issued in August 1908, financed by John V. Dittemore, who had been a businessman in Indiana, was serving as Committee on Publication for the state of New York, and would be appointed Clerk and a Director of The Mother Church in 1909. Mrs. Eddy felt, however, that the time was not right for a biography of her and requested Alfred Farlow, Manager of the Committees on Publication, to see whether its circulation could be stopped.4

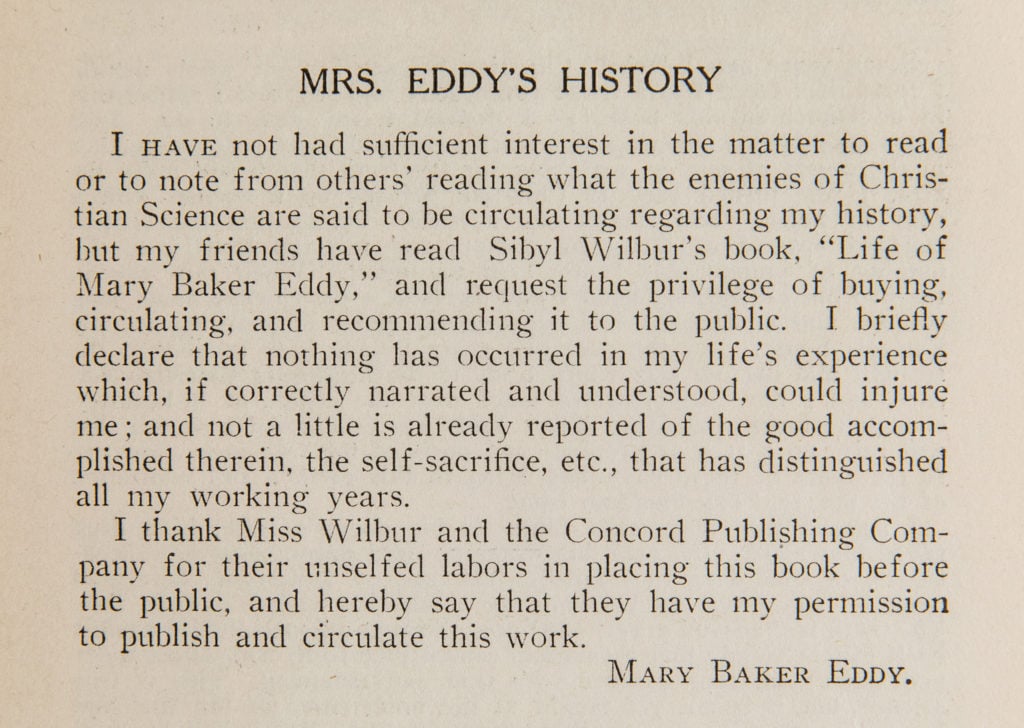

When the news reached Sibyl Wilbur, she at first apparently acquiesced; but she also consulted Samuel Elder, one of Mrs. Eddy’s attorneys during the Woodbury libel suit some years earlier, to explore the possibility of legal action to resume sale of her book. This development was reported to Mrs. Eddy, who withdrew her prohibition. She also issued a public statement of her permission for the book to be circulated:

I have not had sufficient interest in the matter to read or to note from others’ reading what the enemies of Christian Science are said to be circulating regarding my history, but my friends have read Sibyl Wilbur’s book, “The Life of Mary Baker Eddy,” and request the privilege of buying, circulating, and recommending it to the public. I briefly declare that nothing has occurred in my life’s experience which, if correctly narrated and understood, could injure me; and not a little is already reported of the good accomplished therein, the self-sacrifice, etc., that has distinguished all my working years.

I thank Miss Wilbur and the Concord Publishing Company for their unselfed labors in placing this book before the public, and hereby say that they have my permission to publish and circulate this work.5

In the heart of this reserved endorsement is Mrs. Eddy’s remarkable declaration that “nothing has occurred in my life’s experience which, if correctly narrated and understood, could injure me.”

Given the hostile press of 1906 and 1907, it is hardly surprising that Sibyl Wilbur’s writing should slide more toward adulation in her biography than in her magazine articles. Yet it is instructive to shake the dust off the Human Life articles and read them afresh with the perspective of nearly one hundred years.

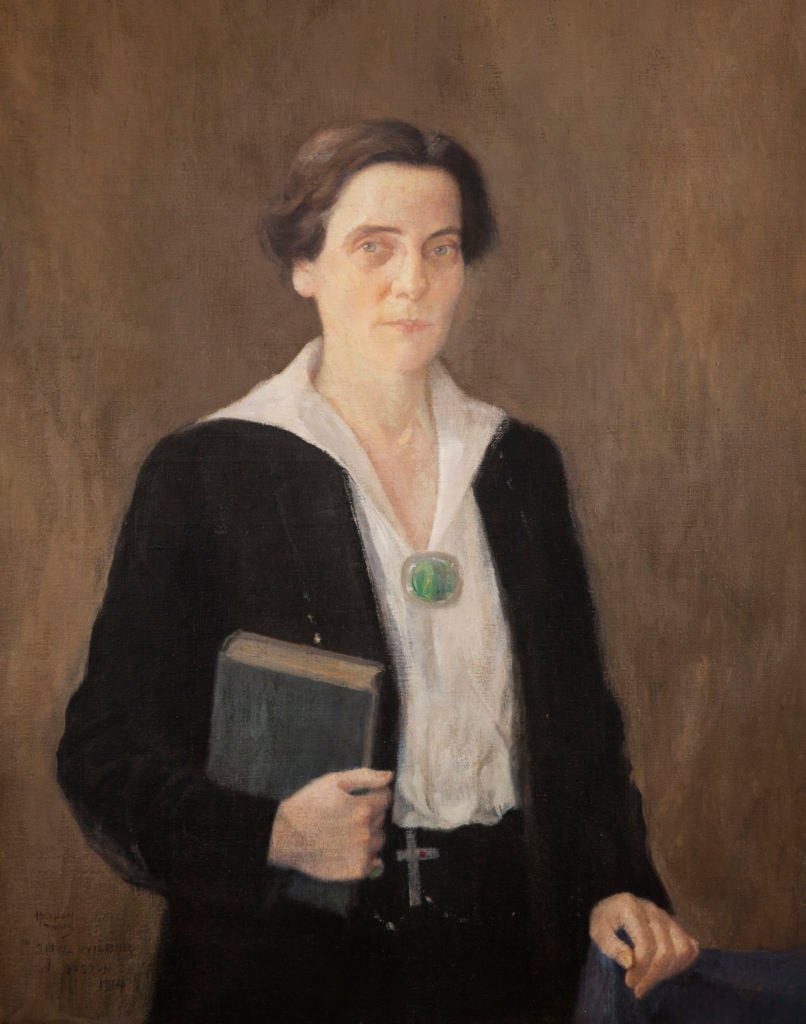

Biographical information about the biographer herself, however, is not plentiful. Sibyl Wilbur was orphaned at a young age, and moved from her native New York State, where she had been born in 1871, to live with relatives in the Midwest. She grew up a Methodist, the religion of her relatives (her father was of Quaker background, her mother a Congregationalist). She attended a Methodist college, Hamline University, in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Attracted to journalism, she worked for the Minneapolis Journal, Minneapolis Times, Chicago Journal, Washington [DC] Times, and the Boston Herald. She served as an overseas correspondent, reporting from Europe. The Birmingham Ledger referred to her as “one of the most widely known newspaper women in the United States.”6 It noted her reporting for the New York World on the conditions of working women, adding that “she was the first writer to start this line of work, which was subsequently taken up by Wyckoff, Upton Sinclair, and many others.” The Ledger also noted her work as Chicago Journal’s labor editor:

She was sent to write accounts of the striking miners in the soft coal district of Illinois and at the time of the memorable Virden riot she scooped the country with her story…. She also reported the big anthracite strike in Pennsylvania and the annual convention of the American Federation of Labor for the Hearst papers and was their special labor reporter, investigating child labor conditions in New York.

About the time Miss Wilbur became interested in writing about Mrs. Eddy, she married a dashing Irishman named O’Brien. It was an unfortunate marriage and did not last. At the time of her marriage, she converted to Roman Catholicism, which she left when the marriage dissolved. She received class instruction in Christian Science from Alfred Farlow in 1907. Though not a member of the Church of Christ, Scientist, she had a large community of Christian Science friends in San Diego, a hundred of whom joined in presenting her with a copy of the “subscription edition” of Science and Health in 1941. At the presentation, Sibyl Wilbur’s close friend Laura Conant, who had served as Second Reader of The Mother Church from 1905 to 1908 and had known her since then, read a brief sketch about her work. Sibyl Wilbur continued to live in San Diego until her passing, on July 21, 1946.

In honor of Women’s History Month, “The Human Life Articles on Mary Baker Eddy by Sibyl Wilbur 1906-1907” is being offered at a special sale price of $15, including shipping. Click here to order your copy!