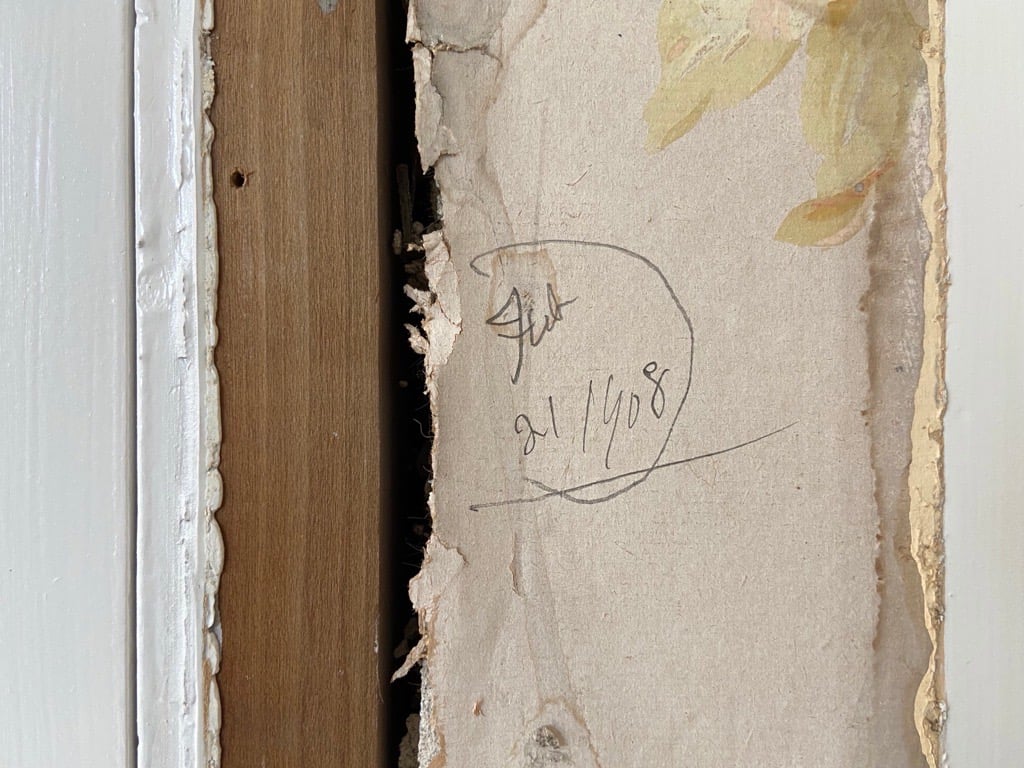

It’s a simple notation in pencil: “Feb 21 1908.” But it’s also important evidence of some of the adjustments made to ensure that Mary Baker Eddy felt at home when she moved to Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts.

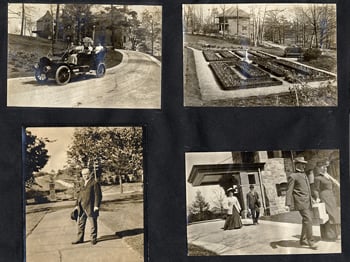

Mrs. Eddy had arrived on Jan. 26, 1908, at the large estate that brought her closer to The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and the Christian Science Publishing Society in Boston, where she would soon be launching a daily newspaper. In early February, she saw the extension of her church edifice for the first time, driving slowly by in her carriage with her longtime assistant Calvin Frye by her side.1

Before she could truly settle in, however, something had to be done about her new bedroom and study, which had been built considerably larger than she had requested.

As the hard-working Discoverer, Founder, and Leader of Christian Science, Mrs. Eddy valued her time. Regarding the great expanse of floral carpet in her study, she quipped that she disliked waiting for her secretary to come to her “across all those roses.”2 In addition, the windowsill in the room was so high that she couldn’t see the drive and the road from her chair.3

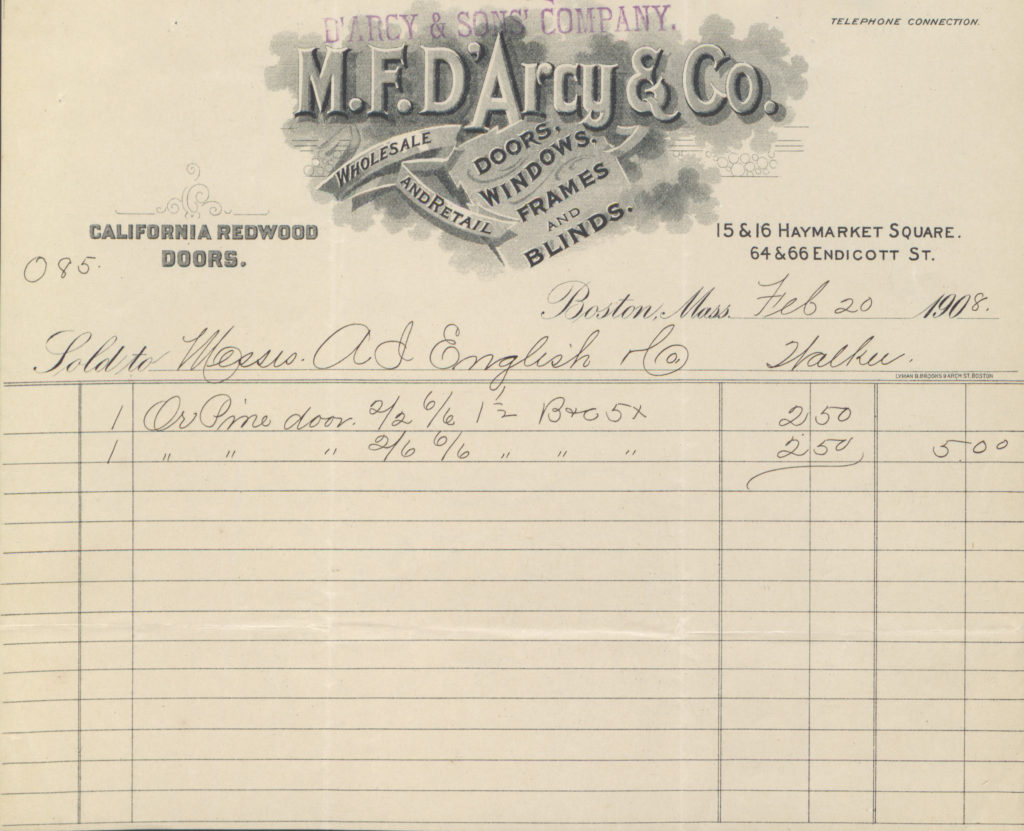

Mrs. Eddy arranged with an architect to renovate her suite to more closely resemble the modest rooms she had been accustomed to at Pleasant View, her home in Concord, New Hampshire. Other adjustments included installing a small private elevator.4

The staff identified a set of rooms on the third floor for Mrs. Eddy’s temporary use, and Nellie Eveleth, her seamstress, graciously moved out of her bedroom and sewing room for the duration of the remodel.

During Longyear’s modern-day work on the restoration of 400 Beacon Street, evidence surfaced of the very day that a small new doorway was built to adjoin rooms in the suite where Mrs. Eddy carried on her work for three weeks in February and March of 1908.

Longyear staff had been carefully removing mantles and door casings at various spots in a hunt for remnants of wallpaper. When they came to this two-foot-wide door, they discovered under the casing not only wallpaper but also a bonus— the “Feb 21 1908” marking, and another mark that could be the initials of a carpenter.

“Finding this little gem was wonderful,” says Pam Partridge, Longyear’s director of education and historic houses. “We were all so grateful to be able to find original evidence.”

Just a few days after the doorway was installed, Mrs. Eddy’s furniture was moved upstairs while she was out on her daily carriage ride.5

“When she got into the bedroom that night she said it was the most homelike room she had seen since she left Concord,” her maid Adelaide Still later wrote, adding that Mrs. Eddy often remarked that Miss Eveleth had “the best rooms in the house” because of the beautiful view.6

Meanwhile, down on the second floor, workmen tackled the renovations in three shifts of eight hours each. Mrs. Eddy attended to such details as choosing a wisteria-bordered wallpaper for the remodeled rooms.7

As Mrs. Eddy oversaw a growing staff and carried on her correspondence, it was not a quiet time at the house, but “the carpenters, plumbers, gasfitters, electricians, painters, paper hangers, and iron workers all did their work smoothly and well, so that the whole change was effected expeditiously and with a degree of harmony that is seldom seen in alteration work of this character,” recalled Adam Dickey, one of her secretaries.8

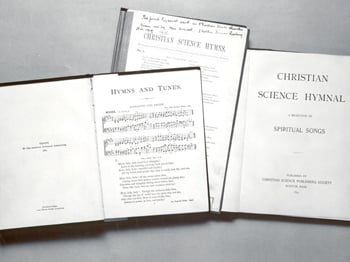

Later that spring, another adjustment would be made on the second floor—the addition of a private sitting room, called the “Pink Room” thanks to wallpaper, upholstery, and carpet in shades of one of Mrs. Eddy’s favorite colors. There, Mrs. Eddy would take time for refreshment, including singing hymns with members of the household gathered around the piano.9

But by March 14, the main renovations were completed. Mrs. Eddy’s furniture was placed back in her bedroom and study during her carriage ride.

Irving Tomlinson made a simple note about her that day: “Moved back. Much pleased with completed rooms.”10