Mary Baker Eddy lived most of her life during the Victorian era, named for the extended period (1837-1901) in which Queen Victoria ruled England. The queen’s influence was felt throughout the world, including in the United States, where Victorian values shaped both American society and style, especially in home décor.

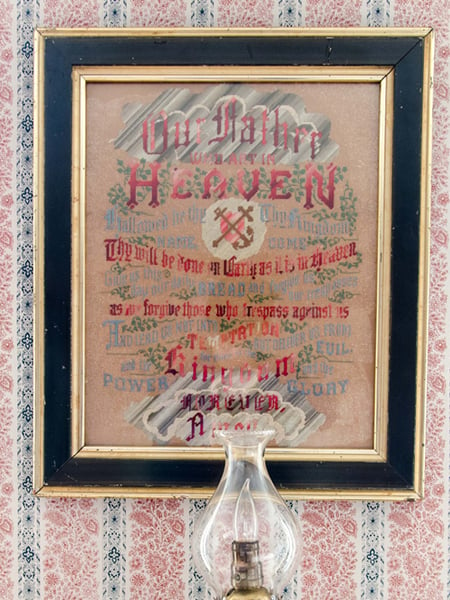

Today, visitors to a historic house from the Victorian era will see the period’s distinct style in full force: an eclectic mix of highly ornamented furniture, wallpaper, and knick-knacks. Nearly all of the Mary Baker Eddy Historic Houses in Longyear Museum’s collection contain examples of this decorative style, particularly in terms of furniture, the characteristic floral patterns and rich, contrasting colors, as well as the images that adorn the walls. And visitors will likely notice one particular type of wall hanging that enjoyed the height of its popularity during the Victorian era: the embroidered punched paper motto.

Mottoes were commonly hung high up on the wall or in an area of prominence, to remind the viewer of their important message, such as “He Leadeth Me” and “Honesty, Industry, and Sobriety.” Short and pithy, they embodied the ideals of Victorian society. Embroidery as an activity was a requisite skill for an accomplished woman, who was expected to make clothes and household goods, but it was also considered a productive pastime. As such, it was a part of Mrs. Eddy’s childhood growing up during the 1820s and 1830s.

Punched paper as an embroidery material first appeared sometime around 1840. Mottoes were initially created in small sizes and found to make excellent bookmarks.1 Longyear has several examples of small pieces that were made by the Bagley sisters, who grew up in Amesbury and were skilled in the fabric arts (Mrs. Eddy would later board at the Bagley home in the summer of 1868 and again in the spring of 1870).

Technological advances contributed to the boom of embroidered mottoes. Whereas before the Industrial Revolution most home décor of this sort was handmade and therefore minimal, now consumers could purchase and fill their homes with all sorts of mass-produced goods.

Pre-printed patterns were widely sold in magazines such as Godey’s Lady’s Book and Harper’s Bazaar. As Diana Matthews writes in an article for Victoriana, embroidered mottoes “… became all the rage and by the 1870’s were desirable to the point of excess. Sometimes called the ‘poor woman’s samplers’ because they were so inexpensive to create, few homes escaped their appeal and examples could be found in every room of the house.”2

Many such period pieces still exist today, often in their original frames. Longyear has a number of examples of mottoes on display in the Mary Baker Eddy Historic Houses, though none of the pieces were owned by Mrs. Eddy personally. However, they do serve to reflect the period in which she lived with its strong interest in the values of home, faith, and Christianity.

One study shows that catalogs from the 1870s and 1880s advertised over 100 different texts.3 Some 10 percent of these mottoes were patriotic in nature, and a large portion commemorated the 1876 Centennial of American Independence. Another 15 percent were associated with fraternal organizations, such as the Masons, Odd Fellows, or the Temperance movement. An additional 15 percent focused on miscellaneous themes, such as home and family. The remaining 60 percent, the largest group, portrayed Christian texts from the Bible and from hymns. The most popular motto by far was “God Bless Our Home,” or variations on it, such as “Home Sweet Home.”

The highly ornate calligraphy seen in these embroidered mottoes was also prevalent elsewhere in Victorian society — in books and advertisements, for example. This particular decorative trend was likely inspired by the lettering in the religious-themed, illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages.4 It’s not surprisingly, then, that in addition to embroidered mottoes, illuminated mottoes were also common in Victorian décor.

This is evident in the interesting history of two versions of one particular motto in Longyear’s collection. “Do Right and Fear Not” is on display in two houses: one as an embroidered motto in the Swampscott house; the other as an illuminated motto in the Lynn house. The illuminated version in Lynn5 can be traced back to Mrs. Eddy’s time in the house during the 1870s, when it hung in her bedroom. The piece apparently stayed in Mrs. Eddy’s possession for the rest of her life, as it was on display at the Massachusetts Metaphysical College in Boston in the 1880s, then in a guest room that Emma Shipman stayed in at Pleasant View, and eventually in seamstress Nellie Eveleth’s room at 400 Beacon Street, after Mrs. Eddy moved to Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, in 1908.6

On the other hand, the embroidered version currently on display at Swampscott belonged to Emma Shipman, who donated it to Longyear in 1938.7 It’s possible that Miss Shipman was fond of Mrs. Eddy’s illuminated piece, and created her own embroidered version as a copy.

Another piece that has traceable historical ties is the embroidered motto “He Shall Give His Angels Charge Over Thee.” It now hangs in the room where Mrs. Eddy stayed when she lived with the Bagley family in Amesbury in 1868. However, it’s possible that Mrs. Eddy never saw this particular framed motto, as it may have been created a decade after her sojourn there. Sarah Bagley’s diary mentions that she framed a motto in 1876, and Longyear’s records indicate this piece was the lone motto in the home’s earliest inventory. So while it’s likely original to the house, it wasn’t necessarily on the wall when Mrs. Eddy lived there. Regardless of its provenance, this is a beautiful and authentic example of Victorian embroidery.

An obvious similarity in all of the mottoes in Longyear’s collection is the religious focus. Given that Mrs. Eddy’s life centered on God and her deep study of the Bible, these mottoes and their Biblical motifs would have been fitting decorations in her rooms. Interestingly, religious mottoes underwent a shift in tone that reflected broader theological changes in American society — a progression also seen in the trajectory of Mrs. Eddy’s own spiritual path.

As a teenager, young Mary could not accept the “relentless theology,”8 as she termed it, of her father’s strict Calvinism, with its unyielding belief in predestination. She would not be alone in this rejection. During the first half of the 19th century, as a series of religious revivals swept the nation, Americans experienced what has since been called the Second Great Awakening, which placed more emphasis on personal salvation over inevitable predestination. One historian notes that by the late 19th century, “hymns and religion in general expressed a new sense of intimacy,” citing a “general ‘softening’ perceptible throughout most forms of Protestantism.”9

This inward shift was mirrored outwardly, reflected not only on church walls of the period but also on the walls at home. A motto text that became popular at this time was a familiar one to Christian Scientists: “God is Love.”

Did Christian Scientists ever create their own framed motto designs, using the words of Mrs. Eddy or ideas unique to Christian Science? There is at least one extant example: an illuminated plaque that originally hung in the first Christian Science Reading Room in Boston. The text “Truth is God’s Medicine for Error of Every Sort” is an early version of a line in Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy. Today, the line on pages 142-143 reads: “Truth is God’s remedy for error of every kind, and Truth destroys only what is untrue.” This original piece is now on display in the Mott Gallery at Longyear Museum.