“Practically the only recreation we had at Pleasant View was photography,”1 said Minnie Weygandt, an early Christian Science worker in Mary Baker Eddy’s Pleasant View home in Concord, New Hampshire, and also at her home in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. Though Mrs. Eddy’s household workers were occupied nearly entirely with their specific responsibilities, be it secretarial, household, or metaphysical work, Miss Weygandt indicates that there was a small amount of time allocated for amusement, and this new phenomenon, photography, was rapidly gaining “enthusiastic amateurs,”2 including those working in the service of Mrs. Eddy.

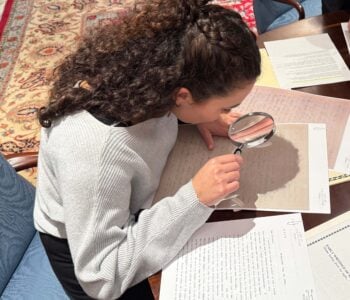

“Most of us had cameras,” Miss Weygandt continued in her reminiscence. “… We did all our own developing and printing. My own camera was an excellent instrument; Mr. Frye said it was the best anyone had there.”3 William Rathvon, Irving Tomlinson, Adam Dickey, Calvin Frye, Laura Sargent, John Salchow, Minnie Weygandt, and Pauline Mann were specifically named by various early workers as amateur photographers, and many of their photographs still exist.4 The snapshots they took, everyday scenes and subjects of interest to them, offer us an invaluable view today of what life was like for a worker in Mrs. Eddy’s home and of their individual photographic styles.

As with any newly emerging technology, there was a flurry of ongoing developments in the photographic sphere happening at this time, and it would take someone with a high level of interest to stay abreast of the latest models of cameras, film, and developing paper. Beaumont Newhall states in his History of Photography that, “Convenient, ready-sensitized dry plates and film of unprecedented speed, ease of processing and printing, fast lenses, quick-working shutters, hand cameras — all these technical advances led to a casual use of photography by untrained amateurs.”5

And though photography had been invented in the early to mid-1800s, it was still a novel and developing medium in 1892 when Mrs. Eddy moved to Pleasant View. Plastic roll film had only been introduced commercially three years earlier by George Eastman, founder of the Eastman Kodak company, later to become the dominant force in the photographic field.6 The amateur photographers in Mrs. Eddy’s home used not only plastic film but its precursor, glass dry plate negatives. Their self-portraits and portraits of others show a small variety of the wide array of cameras on the market at this time, including small handheld cameras like the one pictured above being used by the Lloyd and Mann families.

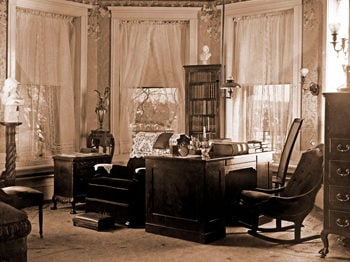

The explosion of technological advancements at the turn of the century was clearly felt by those in Mrs. Eddy’s home, as new inventions were embraced, often without hesitation. Early workers’ reminiscences state that the second automobile to be purchased in Concord, New Hampshire, belonged to Mrs. Eddy and is recorded in photographs,7 though Mrs. Eddy stated that she preferred her horse-drawn carriages.8 Photographs of her homes at Pleasant View and Chestnut Hill also document typewriters, telephones, handheld cameras, and electric lights.

The use of photography in Mrs. Eddy’s home as a hobby that was not just accepted but encouraged is also notable. References to cameras, lenses, and photographic principles can be seen in Mrs. Eddy’s writings, and at least one early worker wrote of her admiring and encouraging their photography.9 Mr. Carol Norton perhaps best summed things up when he included Mrs. Eddy’s own words in an article he wrote after visiting a world exposition fair:

An interesting fact connected with the most startling inventions of recent years is this, that nearly all illustrate metaphysical Truth and serve to confirm the statement that ‘All causation is Mind, and every effect a mental phenomenon.’… Modern discovery and invention, while not divine in themselves, nevertheless lead thought from effect to cause and tend toward a metaphysical basis for all true being and action.10