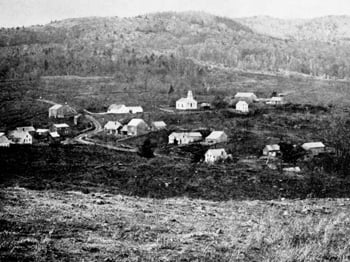

NORTH GROTON, NEW HAMPSHIRE: On a sunny spring day in 2011, a chartered bus carrying forty eleventh-graders wound its way over a twisting road in the foothills of the White Mountains. Climbing higher through dense woods, the bus crossed a bridge over the swiftly flowing Hall’s Brook, full from spring melt, dashing against boulders and rocks, sending up sparkling drops and churning white foam. The driver pulled the bus to the side of the road, parked, and opened the door.

The students, each about the age of seventeen, stepped into the bright sunshine. Before them stretched a lawn dotted with wildflowers. The lawn followed the course of a former road, sloping down to a lone house fifty yards distant, beyond which the grass surrendered to wild growth and trees as the land continued down to where a bridge had once crossed the stream.

The well-cared-for house contrasted with the barely visible ruins of a sawmill opposite it, whose wooden structures had disappeared a century ago and whose stone and metal remains had recently been examined by an archæologist. Upon this sawmill the livelihood of Daniel and Mary Patterson had once largely depended. The noise of the mill, which operated seasonally with water diverted from the brook, must have jarred the peace of nearby residents. The din persisted after another seasonal annoyance: the black flies, biting pests that appear every spring and which the modern students, fresh from the air-conditioned bus, swatted and dodged without complaint.1

When the future Mary Baker Eddy moved into this house, the crucial healing that would lead to her discovery of Christian Science lay more than a decade ahead.2 And now, forty high school students, who had traveled from their jet-propelled present 1,300 miles to reach this house — this isolated witness to the past — must have wondered: What could possibly have happened HERE, in this remote place, that would be relevant to Mrs. Eddy’s discovery of Christian Science?

A great deal, actually — events that altered the trajectory of Mary Baker Eddy’s life: the tragic separation from her son, and an incident to which Mrs. Eddy referred in a court proceeding a half-century later as “my first discovery of the Science of Mind.”3

This article is concerned with that first discovery.

A Gracious Preparation4

When Mrs. Patterson moved to North Groton in April 1855, she was already a decade into a twenty-year search “to trace all physical effects to a mental cause.”5 The origins of her search reached back to her childhood:

“From my very childhood I was impelled, by a hunger and thirst after divine things, — a desire for something higher and better than matter, and apart from it, — to seek diligently for the knowledge of God as the one great and ever-present relief from human woe.”6

It would require years of gracious preparation for her to receive the answer to this search. The preparation included study and practice of homeopathy, which furnished her with evidence that causation did not reside in matter:

“The author’s medical researches and experiments had prepared her thought for the metaphysics of Christian Science. Every material dependence had failed her in her search for truth; and she can now understand why, and can see the means by which mortals are divinely driven to a spiritual source for health and happiness.”7

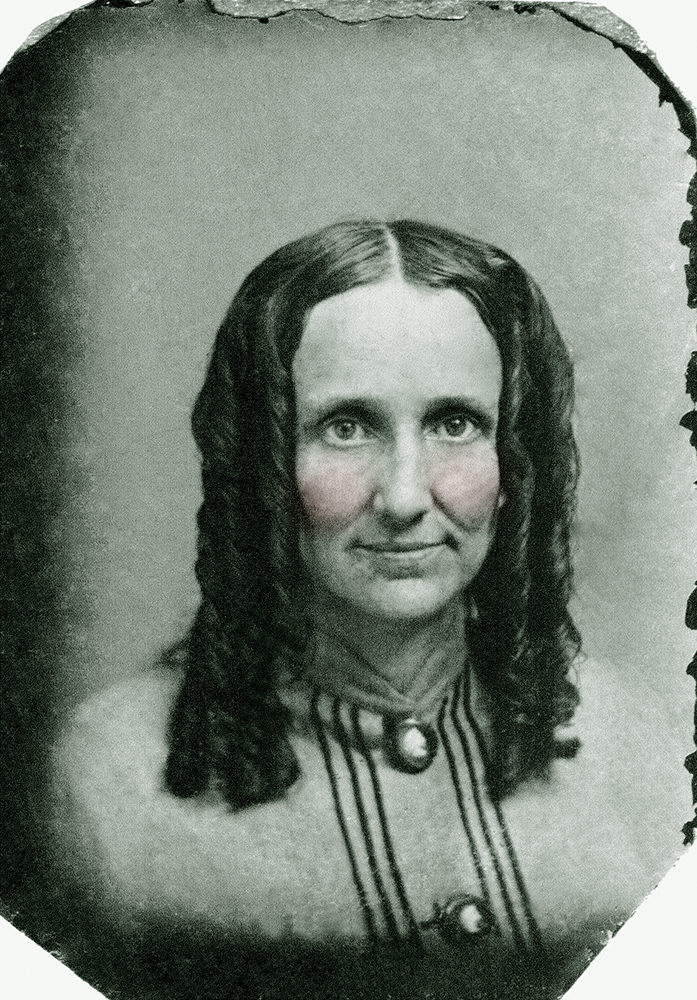

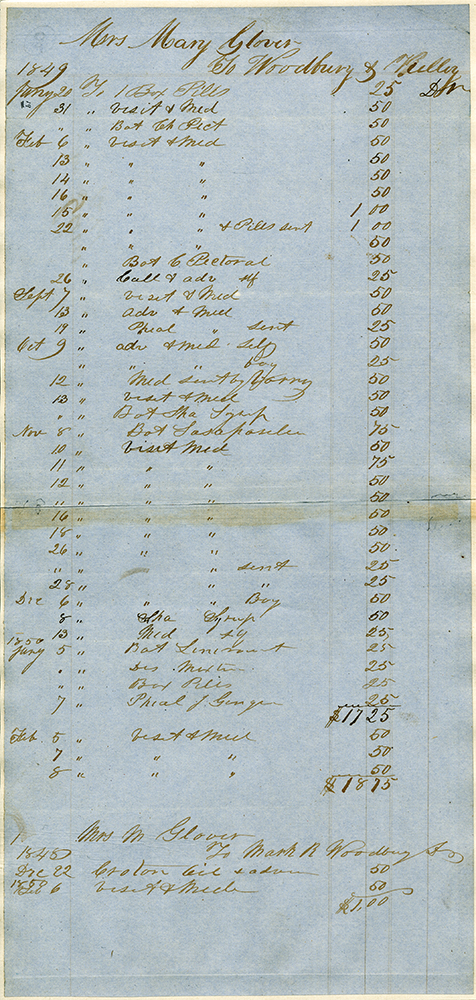

When she was in her mid-twenties, widowed, in poor health, and struggling to provide a home for herself and her young son, Mrs. Glover learned of homeopathy from a cousin by marriage, Dr. Alpheus Morrill.8 A graduate of Dartmouth Medical School, this six-foot-five-inch champion of homeopathy was noted for “his unbounded benevolence, deep sympathy with all in affliction, and kindness to the poor.”9 A pioneer homeopathic physician in New Hampshire, Morrill opened a practice in Concord in 1848 — about the time that Mrs. Glover’s twenty-year search for mental causation commenced. Morrill occasionally prescribed homeopathic remedies for her, and they discussed homeopathic theory and practice.10

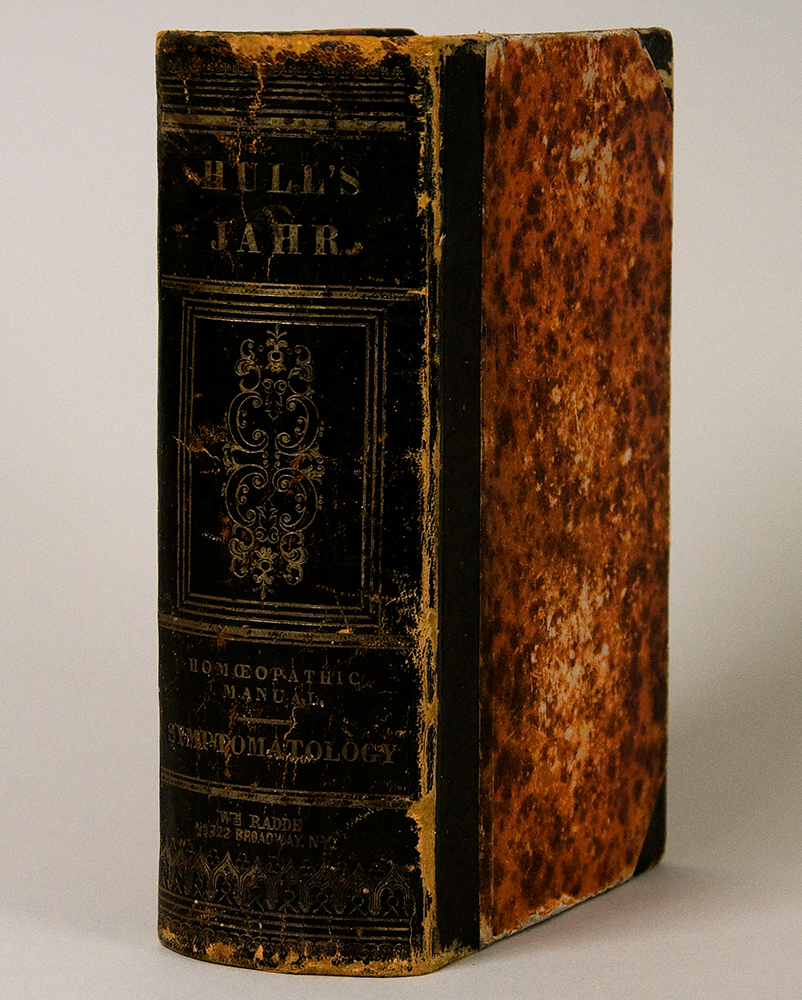

Although homeopathy is popularly known for its extreme dilution of medicine, its fundamental proposition is “Like cures like” — that is, if a drug produces certain symptoms in a healthy person, the same drug may relieve those symptoms in a sick person.11 Symptoms were not confined to the physical but included emotional and mental symptoms, referred to in a standard work of the time as “moral symptoms.”

To attenuate, or dilute, a liquid drug, 10 drops of the drug would be mixed with 90 drops of alcohol; if the drug was in powdered form, 10 grains of the drug would be mixed with 90 grains of sugar of milk.12 The liquid would then be well shaken or the powder “triturated” (that is, pulverized, from a Latin word for “thrash”). The result would be the first attenuation of the liquid or the first trituration of the powdered drug. This process would be repeated to produce the second attenuation or trituration; repeated again to produce the third, and so on, theoretically without end. In her 1898 article, “To the Christian World,” Mrs. Eddy mentions “the one thousandth attenuations and the same triturations of medicine.”13

Diluting the drug was not seen as weakening it but as liberating it to act more powerfully. The attenuated drug could be further diluted when administered, as Mrs. Eddy describes:

One drop of the thirtieth attenuation of Natrum muriaticum, in a tumbler-full of water, and one teaspoonful of the water mixed with the faith of ages, would cure patients not affected by a larger dose.14

Attenuation provided Mrs. Patterson with evidence from which she drew radical conclusions regarding the mental cause of phenomena. Where others looked for chemical or physiological explanations of the attenuated drug’s effectiveness, Mrs. Patterson discerned that the process — “shaking the preparation thirty times at every attenuation”15 — affected the thought of the person preparing the medication, strengthening confidence in it. Reflecting on this process years later, Mrs. Eddy wrote:

To prepare the medicine requires time and thought; you cannot shake the poor drug without the involuntary thought, “I am making you more powerful,” and the sequel proves it; the higher attenuations prove that the power was the thought, for when the drug disappears by your process the power remains, and homœopathists admit the higher attenuations are the most powerful.16

Mrs. Eddy perceived that faith in the drug was not the only factor at work. She discerned that while the drug as matter was no longer present, the drug as a mental condition persisted, “rarefied to its fatal essence, mortal mind”:

The drug disappears in the higher attenuations of homœopathy, and matter is thereby rarefied to its fatal essence, mortal mind; but immortal Mind, the curative Principle, remains, and is found to be even more active.17

The diminishing of the drug does not disprove the efficiency of the homœopathic system. It enhances its efficiency, for it identifies this system with mind, not matter, and places it nearer the grooves of omnipotence.18

Her practice of homeopathy was providing Mrs. Patterson with evidence that “all physical effects” were indeed the result of “a mental cause.” But this evidence raised further questions concerning the nature of the mental cause and how it operated, questions which could ultimately be answered only through divine revelation.

Another feature of homeopathy also engaged Mrs. Patterson’s attention: its consideration of the patient’s mental state. “Homœopathy takes mental symptoms largely into consideration in its diagnosis of disease.”19

The homeopathic manual that Mrs. Patterson studied describes not only physical symptoms but also mental and emotional states that were thought to be caused by particular drugs and consequently potentially remedied by the same drugs. The following entries illustrate homeopathy’s consideration of the patient’s emotional and mental states (referred to as “moral symptoms” in contrast to physical symptoms; the word “want” is used in its meaning of “lack”):

CAPSICUM ANNUUM. . . . MORAL SYMPTOMS.—Taciturn, obstinate and peevish. . . . Want of disposition to work or think. . . .

COFFEA CRUDA. . . . MORAL SYMPTOMS.—*Great anguish. . . . Excessive relaxation of body and mind. Want of memory and attention. . . .

MORAL SYMPTOMS.—Sadness, generally preceded by ecstasy. Lowness of spirits. Melancholy. Sullen mood. . . . Anxiety. . . . Great cheerfulness. Daring boldness….20

Through her study and practice of homeopathy, Mrs. Patterson was being prepared for what would be revealed in the Science of Christianity, as she later wrote:

Years of practical proof, through homœopathy, revealed to her the fact that Mind, instead of matter, is the Principle of pathology; and subsequently her recovery, through the supremacy of Mind over matter, from a severe casualty pronounced by the physicians incurable, sealed that proof with the signet of Christian Science.21

Several critical events would occur, however, before that proof was sealed.

“A falling apple”

While living in North Groton, Mrs. Patterson was asked to assist a woman afflicted with severe dropsy. The homeopathic doctor who had been treating the case held no hope for the woman’s recovery and had given up the case. Mrs. Patterson “prescribed the fourth attenuation of Argentum nitratum with occasional doses of a high attenuation of Sulphuris.”22

The woman began to improve, but Mrs. Patterson grew concerned when she learned that the doctor had prescribed the identical treatment. Still “believing … somewhat in the ordinary theories of medical practice,” Mrs. Patterson felt that prolonged use of the medication would aggravate the symptoms.23

She informed the patient of her concern, but the patient refused to give up the medication. Mrs. Patterson faced a dilemma: how could an aggravation of symptoms be avoided when the patient was unwilling to give up the medication? It occurred to Mrs. Patterson “to give her unmedicated pellets and watch the result”:

I did so, and she continued to gain. Finally she said that she would give up her medicine for one day, and risk the effects. After trying this, she informed me that she could get along two days without globules; but on the third day she again suffered, and was relieved by taking them. She went on in this way, taking the unmedicated pellets, — and receiving occasional visits from me, — but employing no other means, and she was cured.24

This incident has sometimes been depicted as though Mrs. Patterson were experimenting with placebos, but such an explanation may be misleading. Mrs. Patterson was not testing a theory by experimenting upon a seriously ill neighbor; rather, she was seeking to prevent an aggravation of symptoms, and her insight regarding faith in the drug came after the woman’s recovery.

As she considered the evidence — there had been no medication in the sugar pellets to begin with and yet the woman was cured — Mrs. Patterson was forced to conclude that drugs, and consequently matter, had no intrinsic power. This was a watershed breakthrough in her search for mental causation. In a legal hearing a half-century later, in 1907, she identified this insight as her “first discovery of the Science of Mind”:

That was my first discovery of the Science of Mind. That was a falling apple to me — it made plain to me that mind governed the whole question of her recovery.25

While this discovery brought clarification, it also raised questions: How was she to understand this evidence in the light of Christianity? What was the nature of mental healing? If the healing came through the “carnal mind,” was it not, in St. Paul’s words, “enmity against God” and therefore to be classified as sin?26 But if this healing was from “the mind of Christ,” it would be consistent with Christianity and would point to a restoration of primitive Christian healing.27 As Mrs. Eddy explained to the court-appointed masters in 1907:

I was always praying to be kept from sin, and I waited and prayed for God to direct me.28

When I came to the point that it was mind that did the healing, then I wanted to know what mind it was. Was it the Mind which was in Christ Jesus, or was it the human mind and human will?29

It would be several years before she would have the answer.30

“All Science is a revelation”31

The Pattersons left North Groton in 1860, living in various places before renting the second floor of a house in Swampscott, Massachusetts, in October 1865. During these years, their bittersweet marriage became increasingly strained, and they separated in August 1866.32 Jarring experiences were also part of Mrs. Eddy’s gracious preparation:

The trend of human life was too eventful to leave me undisturbed in the illusion that this so-called life could be a real and abiding rest. All things earthly must ultimately yield to the irony of fate, or else be merged into the one infinite Love.33

On February 1, 1866, Mrs. Patterson suffered a serious accident that threatened to be the final irony of fate. By Sunday, February 4, it appeared to her friends that she would not survive. That afternoon she requested them to leave her alone with her Bible. Reading an account of Christ Jesus’ healing, she “suddenly felt a new comprehension” of his words, “I am the way, the truth, and the life: no man cometh unto the Father, but by me.”34 She found herself healed through spiritual means alone. The life-changing significance of this healing was not immediately clear to her. Only in retrospect did she come to see it as the watershed event leading to her discovery of Christian Science.35

The healing itself was not the understanding of how the healing had taken place. A revision Mrs. Eddy made to her 1885 pamphlet, Historical Sketch of Metaphysical Healing, illustrates this. In 1885 she wrote:

Twenty years prior to my discovery I had been tracing all physical effects to a mental cause, and in January of that year [1866] gained the certainty in science that all causation is Mind, and every effect a mental phenomenon.36

In the summer of 1891 while expanding and revising the pamphlet for a new book, Retrospection and Introspection, she considered this sentence afresh. Significantly, she did not revise “January” to “February,” the month in which her healing had occurred. Instead, she replaced “January” with “the latter part of 1866” — the better part of a year after her February healing:

During twenty years prior to my discovery I had been trying to trace all physical effects to a mental cause; and in the latter part of 1866 I gained the scientific certainty that all causation was Mind, and every effect a mental phenomenon.”37

What had happened between her healing in February and the latter part of 1866 that had brought her “the scientific certainty,” thus concluding her twenty-year search for mental causation? In the months following her healing, Mrs. Patterson became aware of a phenomenon: if, when she visited neighbors who were ill, she had the same spiritual uplift of thought that she had had when she was healed in February, her neighbors would be healed.38 Here was mounting evidence of pure, spiritual healing rooted in the New Testament, and in the latter part of 1866, she reached certainty concerning the mental cause of physical phenomena, bringing to a close her twenty-year search.

There remained, however, the question of how the healing was accomplished, which at the time seemed to her a “mystery.”39 She was not content to let it remain a mysterious, miraculous intervention; it was the Science of healing that she sought:

I knew the Principle of all harmonious Mind-action to be God, and that cures were produced in primitive Christian healing by holy, uplifting faith; but I must know the Science of this healing, and I won my way to absolute conclusions through divine revelation, reason, and demonstration.40

She launched into what would prove to be a three-year search. And for this search, she turned to the source of her healing in February, the Bible:

The Bible was my textbook. It answered my questions as to how I was healed; but the Scriptures had to me a new meaning, a new tongue. Their spiritual signification appeared; and I apprehended for the first time, in their spiritual meaning, Jesus’ teaching and demonstration, and the Principle and rule of spiritual Science and metaphysical healing, — in a word, Christian Science.41

A century and a half after the Pattersons left North Groton, visitors from all over the world come here to see where Mary Baker Eddy had once lived. As the seventeen-year-olds walked about this historic site on that spring day in 2011, it was Longyear’s task to convey to them, as to all visitors, something of the magnitude of what happened here. There is continuity between Mrs. Eddy’s research and discovery here and her later work.

“My discovery of Science,” she [Mrs. Eddy] told a household worker in 1902, “was the result of experience and growth. It was not a case of instantaneous conversion in which, I could say, ‘Now the past is nothing, begin entirely anew.'”42

The house, the ruins of the sawmill, the nearby school that her eleven-year-old son attended before their heartbreaking separation, the rugged beauty of the area, the rush of the brook, and even the irksome black flies — all these provide windows onto Mrs. Eddy’s life in the late 1850s.

But what makes the modest house in North Groton of monumental importance in the history of Christian Science is that here Mary Baker Eddy made her “first discovery of the Science of Mind.”