Mary Baker Eddy’s early years were spent in a warm, affectionate family with her mother, father, and five brothers and sisters in the rural beauty of New Hampshire. Longyear Museum’s Baker Family collection of letters and artifacts show some of the unique influences on her early life that helped prepare her for her life as Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science.

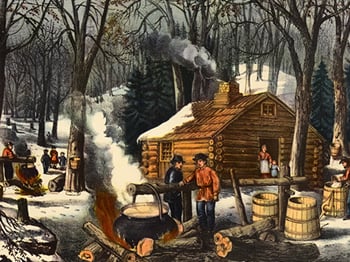

THE BAKER FAMILY OF BOW AND THEN TILTON, New Hampshire, might appear, if one were to examine the flow of events at the surface of life, almost interchangeable with many other nineteenth-century New England families.

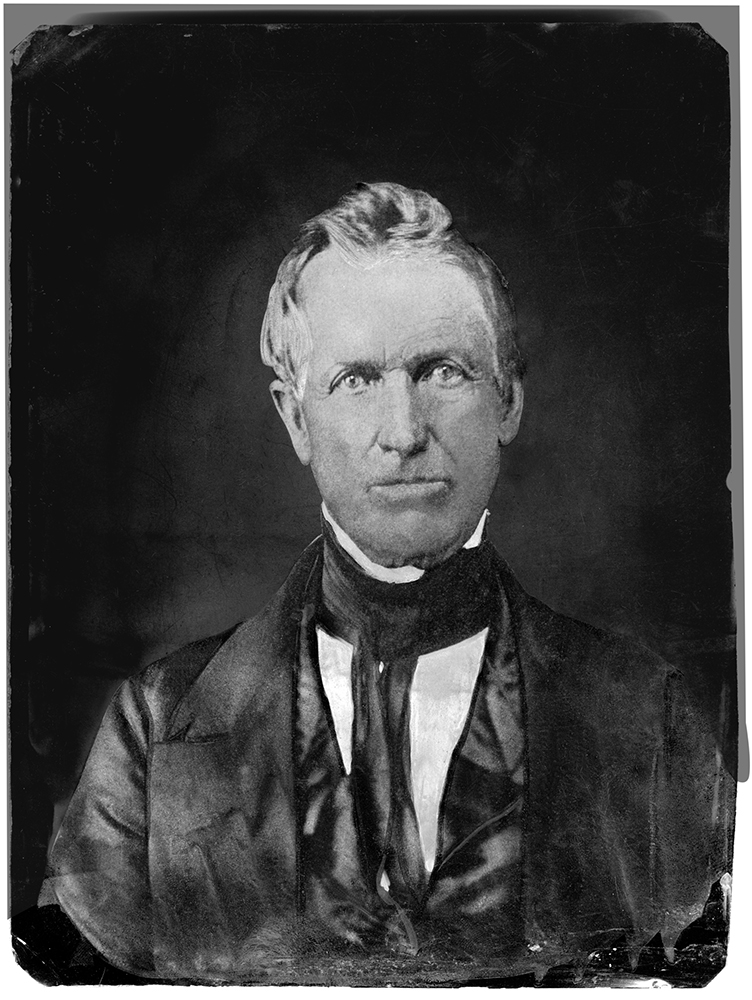

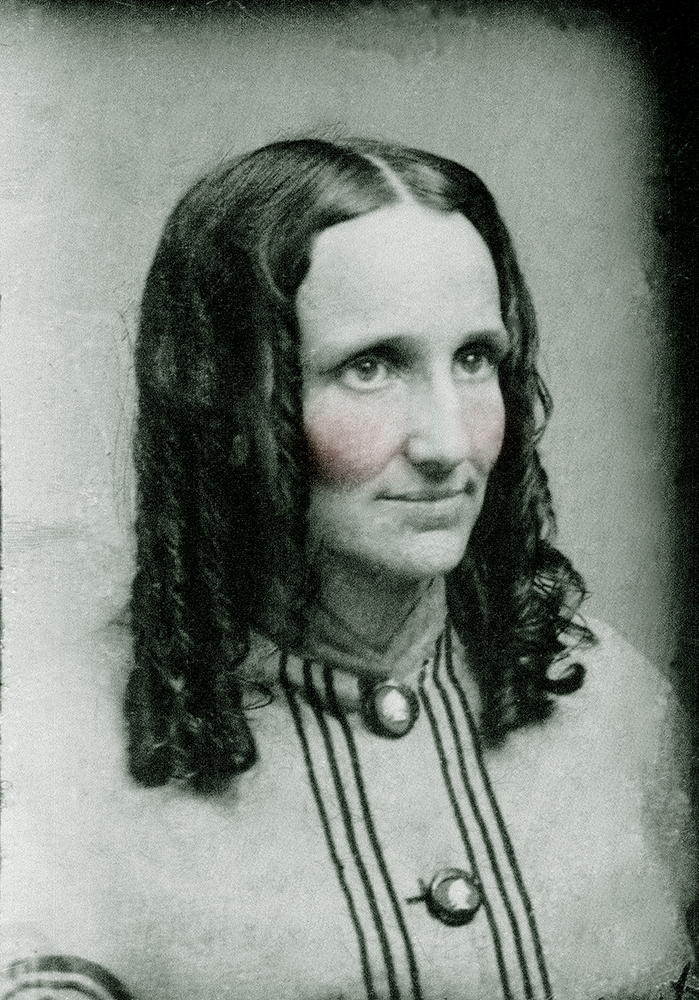

Father, Mark Baker, and wife, Abigail, raised their six children — three sons, Samuel Dow (b. 1808), Albert (b. 1810), George Sullivan (b. 1812), and three daughters, Abigail Barnard (b. 1816), Martha Smith (b. 1819), and Mary Morse (b. 1821) — in Christian devotion anchored in Puritan tradition.

The importance of family, hard work, and education, and a reverence for the Bible and church were all taught and reinforced daily, and within the safety of these moral guideposts, the Bakers rode out life’s daily joys and struggles.

Mark Baker’s sons, desiring to escape their father’s farming life, launched into other occupations. Brother Samuel left home in his late teen years for Boston to work as a mason and became a successful building contractor. Albert was graduated from Dartmouth College and took up the practice of law, passing the bar examinations of both New Hampshire and Massachusetts. George Sullivan, the romantic, left home in 1835 to work first in Connecticut and later to go into partnership with his brother-in-law Alexander Tilton, a wealthy woolen mill owner.

For the Baker women, education was important, but on an equal footing with finding a suitable husband. Thus, the lively Baker daughters sometimes found themselves at the center of the local social swirl, as attested by Mary Baker’s firsthand testimony.

“We attended a party of young Ladies at Miss Hayes last evening,” fifteen-year-old Mary Baker wrote five days before Christmas in 1836 to her older brother George, who was living in Connecticut at the time. Her letter included the gentle sister-to-brother tease: “she [Miss Hayes] was truly sorry our Brother from Conn. was not there, but she is soon to be married and then the dilemma will close as it is your fortune to have some opposing obstacle to extricate you.”1

Almost four months later, Mary again informed George (whom the family generally called by his middle name, Sullivan) of interesting events on her social calendar. She had made the acquaintance of a “perfect complete gentleman”:

I met him a number of times at parties last winter, he invited me to go to the Shakers with him but my superiors thought it would be a profanation of the Sabbath and I accordingly did not go. But since then … I attended a wedding with a Mr. Bartlett; he was groomsman and I bridesmaid; we had a fine time I assure you.2

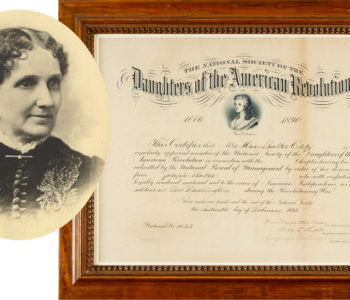

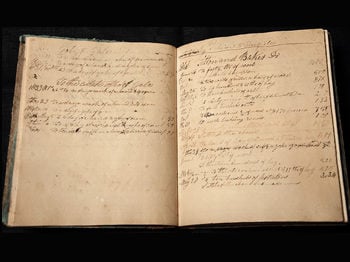

Many such incidents are revealed in the Baker family materials — about 250 documents, including about 170 letters — that form a part of Longyear Museum’s collection. For anyone wishing to explore Mrs. Eddy’s life from child to young adult, especially the years from 1835 to 1844, this collection forms a crucial window through which one can see her as a warm, playful, and affectionate Baker family member with a developing sense of spiritual commitment.

In addition to the papers, the collection includes about 175 artifacts, which had been owned by Baker family members, such as a spinning wheel used by Mrs. Eddy’s grandmother, as well as a table, mirror, oil lamp, and a pen-and-ink case (these and other Baker family materials are included in Longyear Museum exhibits).

The collection started as early as July 1910, when the spinning wheel that had belonged to Mrs. Eddy’s grandmother was given to Mary Beecher Longyear, founder of Longyear Museum. During the next two decades, Mrs. Longyear started gathering historic documents and artifacts that show some of the earliest history of the founding of Christian Science. Seeing the impending loss of historic items and landmarks, Mrs. Longyear was able to locate Albert Baker’s papers that had been retained by George Waldron Baker, son of Mary Baker Eddy’s brother, George Sullivan Baker. That collection of papers was discovered in a trunk after the passing of Martha Rand Baker, Sullivan’s widow.

The collection of letters and papers shows not only household events but also a current that was moving deeply in Mary Baker’s life and taking her in a spiritual direction. Speaking decades later about this spiritual impulsion at work in her early years, Mary Baker Eddy, the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, wrote:

From my very childhood I was impelled, by a hunger and thirst after divine things,—a desire for something higher and better than matter, and apart from it, — to seek diligently for the knowledge of God as the one great and ever-present relief from human woe.3

Mary was blessed to live in a home where the knowledge of God was cherished. Her father, Mark Baker, loved the Bible, as well as a good debate on some point of theology. Mary loved listening and learning from these discussions, and they would form some of her first lessons in how to distinguish tares from wheat. She did not blindly accept everything she heard. Listening, for Mary, was only a first step. The critical next step was what she did with what she heard. Asked in her later years if listening to these sometimes heated, sometimes long-into-the-night debates tired her, Mrs. Eddy responded:

Never — I always wanted to know who won. It was always my joy to listen to a sermon or to hear a discussion upon a Bible subject. After hearing it, I would go over it again and again and pray over it far into the night.4

That Mary went over a discussion “again and again” and prayed over it “far into the night” shows she was, at this young age, carefully weighing what she heard from others. Mary would also spend many a free childhood hour in spiritually productive ways. While other children might be out playing in the sun, she later wrote, she found that sometimes there were more important things to do:

Even in my childhood days, I would much rather study the Bible or listen to a discussion of it than to go out to play with the children. After school I would seat myself in the rocker, and while I rocked read the Psalms of David or the life of the Master.5

The atmosphere of the Baker home included the influence of her brother George Sullivan and his own quest to find meaning and happiness in life. Even as Mary learned from her brother Albert, whose instruction included some lessons in the original biblical languages of Greek and Hebrew, she would also find encouragement from Sullivan.

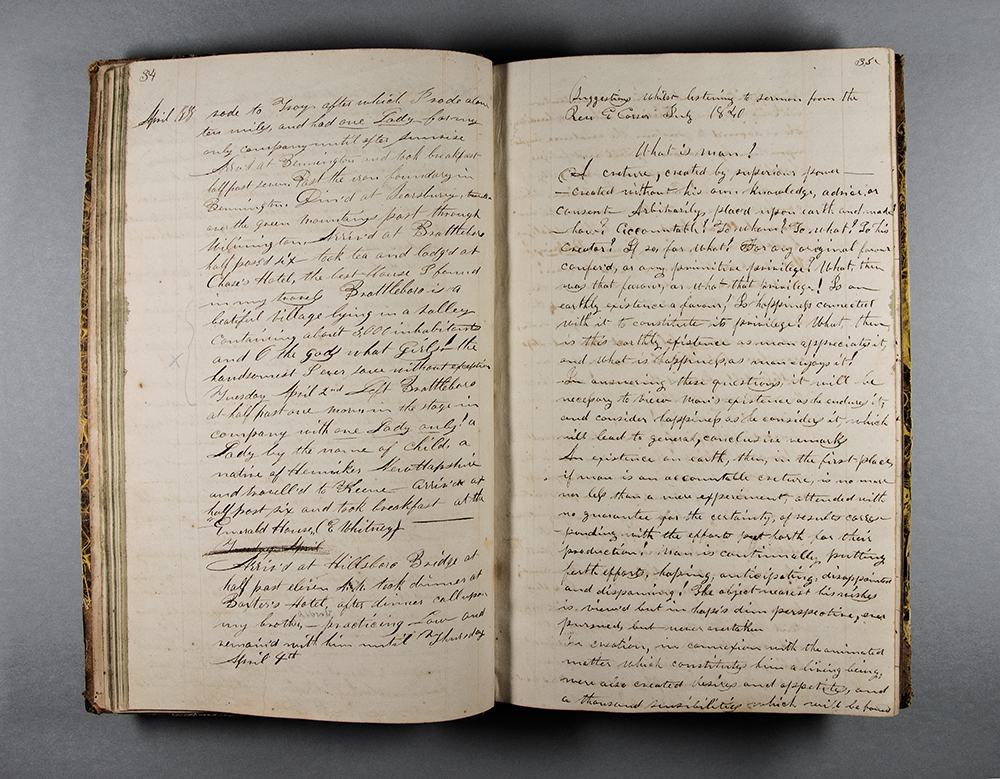

We can see some of the deep questions that Sullivan wrestled with in essay-like notes written by him while he listened to a sermon delivered in July of 1840 by the Reverend Enoch Corser, pastor of the Congregational church of which Mary and her parents were members. The serious questions Sullivan asks himself had no doubt been the kinds of subjects that had been points of discussion around the Baker hearth across the years.

Man had been created upon earth —“how?” Sullivan asked.

Accountable? To whom? To what? To his creator? If so, for what? For any original favor confer’d, or any primitive privilege?What, then was that favor, or what that privilege! Is an earthly existence a favor? Is happiness connected with it to constitute its privilege? What, then, is this earthly existence as man appreciates it, and what is happiness, as man enjoys it!6

Mary was deeply inspired by church attendance and her own daily study of the Bible. Certainly by the age of twelve she was versed in Biblical issues and interpretations, and she probably professed faith at a revival meeting held in April 1834.

Decades later she recalled her struggle over the doctrine of predestination and her refusal to accept it, when joining the church — a rejection her father and other devout members of the church would consider heretical. Mary and her father got into a heated debate, and she developed a fever. Her mother bathed her forehead and told Mary to “lean on God’s love.”After turning to God in prayer,Mary felt a “soft glow of ineffable joy” come over her, and the fever broke.7

When the time came for the meeting to examine candidates for membership, Mary held her ground and refused to accept this doctrine. Nonetheless, she was accepted into membership,8 the church records stating that she joined by “profession of faith.” But it is interesting to note that with her discovery of Christian Science, Mrs. Eddy would write that “More than profession is requisite for Christian demonstration.”9

Her early religious experience and training were important preparation for her, and later in life Mrs. Eddy would write of her great love for the Christian ministers who in her younger years pointed her in the direction of the primacy of the Word of God:

Such churchmen and the Bible, especially the First Commandment of the Decalogue, and Ninety-first Psalm, the Sermon on the Mount, and St. John’s Revelation, educated my thought many years, yea, all the way up to its preparation for and reception of the Science of Christianity.10

Mary seemed to sense, even in these early years of her life, how she might be able to lend assistance to those needing healing. After discovering that her brother Sullivan was struggling with illness, Mary scolded him in a January 22, 1848, letter for keeping his condition quiet: “Why did we not hear that you were sick? but ’tis well if we could give you no relief, that we should not know it; yet Geo. you cannot conceive what a strange spirit I possess in such things.”

Mary then tells him she had dreamed of him for the past three nights and “always awoke in trouble.” She continues: “Oh! if I could be near you when you suffer, I might prove by acts what it is no use to talk about;…”11

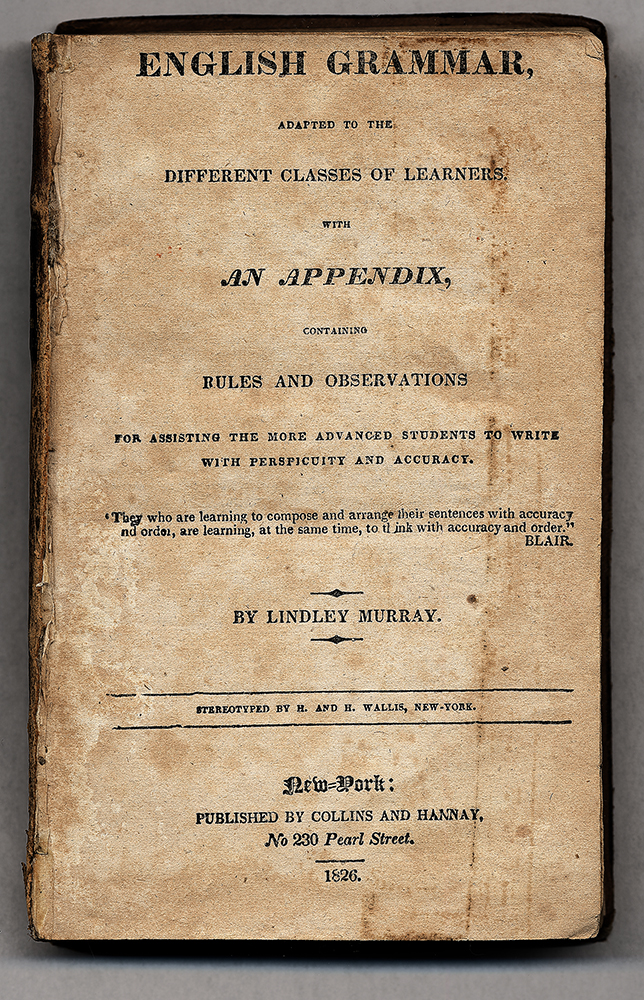

The collection also shows the early development of Mrs. Eddy as writer, and she would draw upon this capacity in her work founding Christian Science. Mary studied her copy of Lindley Murray’s English Grammar. She was also an avid reader, savoring the works of some of the great writers, such as Shakespeare.

When sister Martha offers up a verbal snapshot of family activities in a May 1, 1836, letter to brother Sullivan, Mary is seen as engaged in one of her favorite pastimes:

Father and Mother have just retired and left Mr. Cutchins and us girls to amuse ourselves; so he and I are writing, Mary is reading, and Abba [sister Abigail] sits and orders me what to say but I shall not regard her.12

The influence that reading and writing had on Mary can be traced in her formal and informal writing, from her poetry to letters to family members. While the earliest letters contain misspellings and at times an unpolished tone, albeit from a playful pen, by her mid- to late-teen years Mary’s style is just beginning to take shape and with an impassioned, affectionate, and playful voice.

A fifteen-year-old Mary explained her approach to writing this way: “I always write to [you] from the impulse of the moment,” Mary wrote George. After informing her brother, then living in Connecticut, about the dwindling number that now sat around the Baker family dinner table — originally nine members, the number would be just four after Abigail married and left home — Mary paints him a word picture of life at home:

Abigail is preparing for the celebration of her nuptials, probably, as soon as June; then there will be another tie severed, she will be lost to us irrevocably, that is certain, although it may be her gain. How changed in one short year! Dear brother can you realize it with me? If so just take a retrospect view of home, see the remaining family placed round the blazing ingle scarcely able to form a semicircle from the loss of its number.13

After pleading with him to return home and join the family circle, she casts a metaphor that shows an early use of what would become her sense of the power of language. “If not,” she writes, “I shall have still longer to gather honey from the flowers of the imagination.”

That the Baker Collection of family letters allows us to learn something of the details of their daily life is due in part to the fact that these family members were letter-writers. When George or Albert moved away from home, they kept up with events by sending and receiving letters. It is from these that today’s reader can see some of the choices Baker family members made.

This point is nicely summed up by Mary’s older brother Albert, who advises his younger brother Sullivan that each person must find his own way in the world:

I could say a great many things by way of advice, but it is of no use; to deal with the world, is something that cannot be taught on paper, each one must learn the trick for himself.14

And that is what the Baker Family Collection shows us today — a little of how these family members went about learning “the trick” for themselves. For the girl who would one day be known as the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, that meant moving from fashionable dresses and parties to the things that eye cannot see and ear cannot hear — the things of the Spirit.