The World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893

The World’s Fair which was held in Chicago in 1893 was known as the World’s Columbian Exposition; it commemorated the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s voyage to the Americas. As a forerunner of the world’s fairs of the 1900s, it was international in scope. Exhibits of commercial, industrial and scientific interest were housed in buildings constructed specifically for the occasion.

Each building was designed by a different architect. The exteriors of many were white, giving the fairgrounds the nickname “the White City.” The Women’s Building was the only one designed by a woman, a 21-year-old graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology named Sophia Hayden. Mary Cassatt, an American artist who later exhibited with the French Impressionist group of painters, was commissioned to paint one of the decorative murals.

Some innovations introduced at the 1893 Exposition

- Cracker Jack (a molasses popcorn snack) was introduced at the Fair.

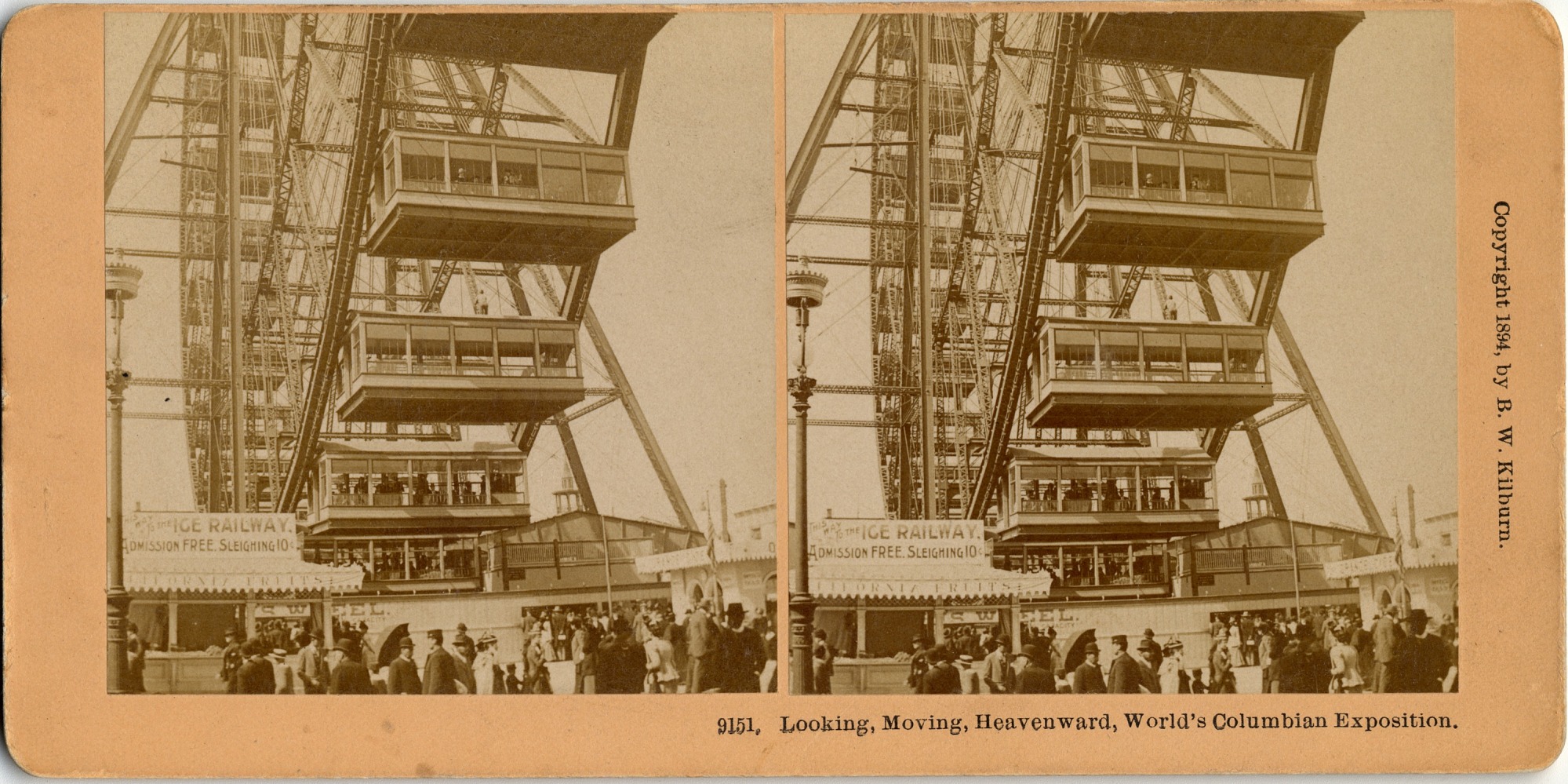

- The Ferris Wheel, invented by the engineer George Ferris, was the winner of the competition sponsored by the Fair for something “novel, original, daring, and unique.”

- A special commemorative coin, the Isabella quarter, was minted for the Fair. Issued in recognition of the support given to Christopher Columbus by Queen Isabella of Spain, it was the first U.S. coin to bear the portrait of a woman.

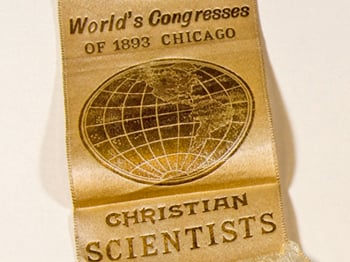

Christian Science at the World’s Columbian Exposition

Christian Science Exhibit

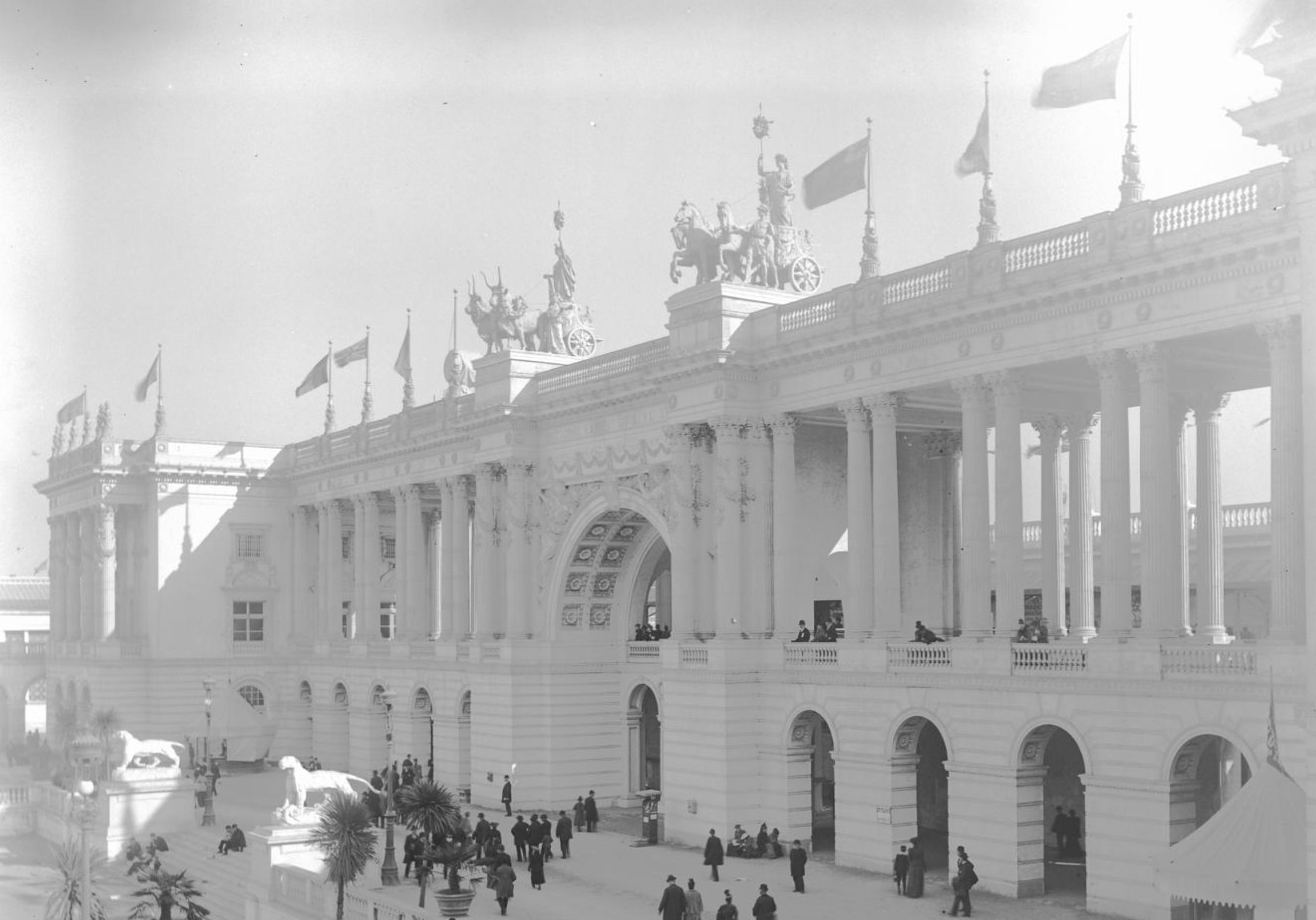

Christian Science was well represented at the World’s Columbian Exposition and related activities. An exhibit of Christian Science literature occupied a choice location at the top of a staircase in the Publisher’s Department in the huge Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. Several thousand copies of Mary Baker Eddy’s writings and other pieces of literature were exhibited.

World’s Parliament of Religions As an auxiliary to the World’s Columbian Exposition, a World’s Parliament of Religions, also called World’s Congress of Religions, was held. As plans evolved, questions were raised whether religion should have a place at the Exposition. But as the Reverend John Henry Barrows observed:

Why should…the silk weavers of Lyons and the shawl makers of Cashmere, the designers of Kensington, the lace weavers of Brussels…be invited to a World’s Exposition, and the representatives of those higher forces which had made civilization be excluded?….[The World’s Parliament of Religions, 1893, Vol. I, p. 4]

Christian Science figured in two meetings under the World’s Congress of Religions: at a “denominational congress” and at a presentation at the ecumenical session of the Parliament.

The Denominational Congress

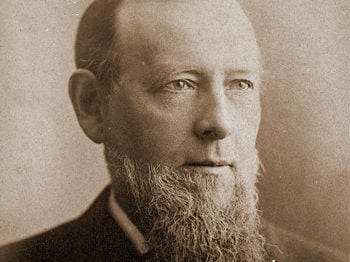

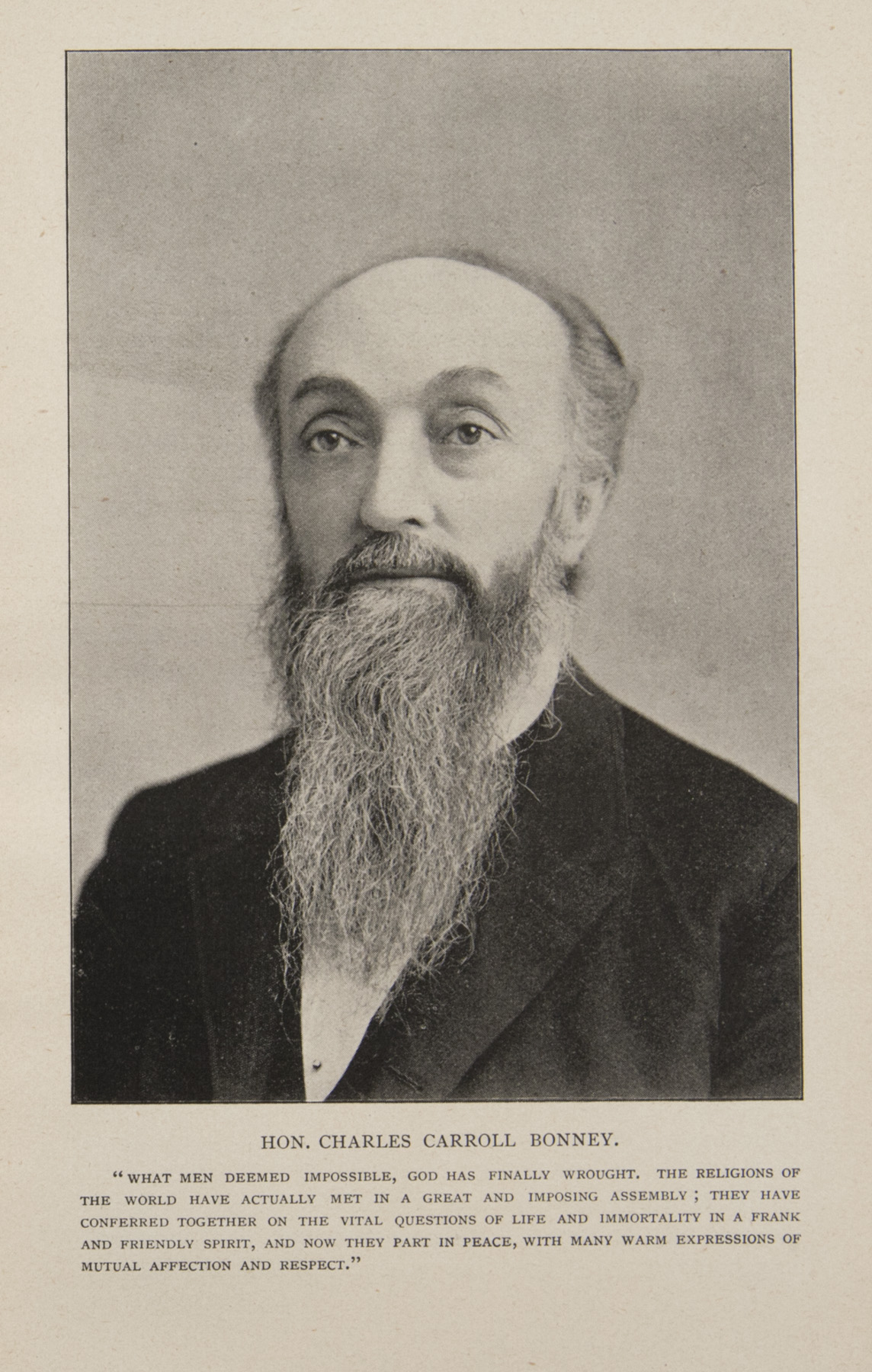

The “denominational congress” was held on September 20, 1893, in Washington Hall, a large room in the Exposition’s Palace of Fine Arts. (This building, which is still standing, is today the Museum of Science and Industry.) The meeting was opened by the President of the World’s Congress Auxiliary, Charles Bonney, who commented:

No more striking manifestation of the interposition of divine Providence in human affairs has come in recent years, than that shown in the raising up of the body of people which you represent, known as the Christian Scientists….

The common idea that a miracle is something which has been done in contravention of law is to be wholly discarded and repudiated.

There is not one miracle recounted in the sacred Scriptures which was not wrought in perfect conformity to the laws which the divine Creator had established. It is mere ignorance of those laws that leads men to think that miracles are acts in contravention of them.

To know the law is to see that the wonder is wrought by means of law, and that the only miracle consists in the wonderfulness of the act which is done.

Who can doubt, in witnessing the tremendous events that are now transpiring in our midst, that the day of miracles is as surely here as it was eighteen centuries ago.

To restore a living faith in the efficacy of the prayer-the fervent and effectual prayer of the righteous which availeth much; to teach everywhere the supremacy of spiritual forces; to teach and to emphasize the fact that in the presence of these spiritual forces all other forces are weak and inefficient- that I understand to be your mission. [The Christian Science journal, Vol. XI, pp. 339-340; see also Mrs. Eddy’s response, Miscellaneous Writings, p. 312.]

Bonney’s introduction was followed by readings from the Bible and Mrs. Eddy’s work, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, and papers by several of Mrs. Eddy’s students, including

Chicago resident Ruth Ewing.

At the end of the Christian Science Congress, at Mrs. Eddy’s request, the National Christian Scientist Association held an adjourned meeting (Journal, Vol. XI, pp. 345-346).

The Parliament of Religions

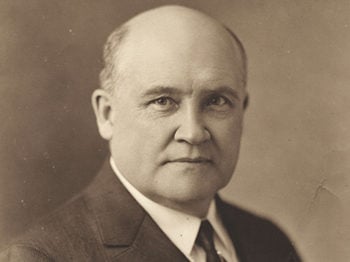

Two days later, on September 22, 1893, an address on Christian Science by Mrs. Eddy was read before the Parliament. Mrs. Eddy carefully selected extracts from her writings for her paper at this ecumenical session. Entitled “Unity and Christian Science,” her address was read by Judge Septimus J. Hanna, editor of The Christian Science journal.

This article was originally published in the Longyear Historical Review, Vol. 37, No. 1.