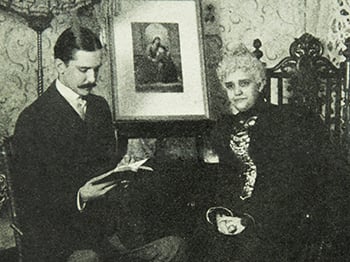

On the day before Christmas, 1899, two visitors from Germany arrived at Mary Baker Eddy’s home, Pleasant View, on the outskirts of Concord, New Hampshire. Visitors from Europe constituted a newsworthy event for turn-of-the-century Concord, and in commenting on the visit, the Concord Monitor stated:

One of the early students of Mrs. Eddy was a German, and to him Mrs. Eddy said, “Germany will be the first European nation to accept Christian Science. Their love of God, their profound religious character, their deep faith, and strong intellectual qualities make them particularly receptive to Christian Science.” [Reprinted in the Christian Science Sentinel, Jan. 4, 1900, vol. 2, p. 283.]

Only a decade after the founding of the Church of Christ, Scientist, in 1879 by Mary Baker Eddy and nine of her students, word of the new religion was being carried beyond North American shores. The religion became known in various ways, more often than not, by word of mouth as one person told another of healing and shared newly gained insights about the Bible and the nature of God. It expanded most rapidly in English-speaking countries and in Germany.

Probably the first person to make Christian Science known in Germany was Hans Eckert. A native of Cannstatt, near Stuttgart, he became interested in Christian Science in 1889 while he was living in the United States. He had Christian Science class instruction about 1891 and became a member of The First Church of Christ, Scientist (The Mother Church) in 1893. In 1894 he returned to Germany and introduced Christian Science in the Stuttgart area.

Two other pioneer Christian Scientists in Germany are the subject of this article: Bertha Günther-Peterson, the first German to become an authorized teacher of Christian Science, and Frances Thurber Seal, who was active in Dresden and Berlin.

Bertha Günther-Peterson

Bertha Günther-Peterson grew up in Kirn-ander- Nahe, about 40 miles southwest of Mainz. Her father and her husband were both physicians. Widowed while her daughters were still young, she moved to Hannover, where in 1894 she heard of Christian Science through a college friend living in the United States. The friend, Marie Schon, wrote that she had become seriously ill with typhoid fever and had been given up by her doctors. She turned to Christian Science, and a complete healing resulted.

Intrigued by this news, Frau Günther-Peterson ordered a copy of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, by Mary Baker Eddy. From the time that she began to read it, she devoted herself to the study of Christian Science.

In the autumn of 1896 she traveled to New York to study Christian Science under one of Mrs. Eddy’s students, Laura Lathrop, CSD. Returning to Germany in late June the following year, she went to work immediately to introduce Christian Science in Hannover, and started holding worship services in July:

I began to read our Bible-lesson on Sundays, with my little family of four, now ten of us meet to read it. We meet every Sunday afternoon in my home, and I know this little congregation will require larger space in due time. [The Christian Science Journal, vol. 15, February 1898, p. 704.]

The “due time” may have been sooner than she had expected, for when three Christian Scientists from London visited “the beautiful, clean, prosperous looking town of Hannover” the following year, they learned that:

There was a Sunday morning service held in Frau Gunther’s rooms, attended by some sixty or seventy people, and an experience meeting during the week, at which as many as two hundred were often present, and, after twice moving to obtain more accommodation, it is frequently the case that some have to stand or go away, sometimes to the number of thirty or forty. Much good, and, to others than Christian Scientists, wonderful, work is being done….

There seems to be much in the German character to which Christian Science makes a strong appeal, and all had the characteristic radiant, happy appearance, which made it a great joy and privilege to be amongst them, and far more like meeting old friends than, as was the case, seeing people for the first time.” [Journal, vol. 17, August 1899, pp. 367-368]

From a single patient in 1897, Frau Günther-Peterson found her Christian Science practice rapidly growing so that from early morning people were crowding the stairs to her apartment waiting for an interview: “it was solely the conclusive evidence of spiritual healing which so widely spread the flood of blessings” (biographical sketch of Bertha Günther-Peterson).

Visits Mary Baker Eddy

In 1899, Frau Günther-Peterson made a second trip to the United States to attend a Normal class in Christian Science. On her arrival, however, she learned that the class had been postponed. Undaunted by this setback, she hoped to have an interview with Mrs. Eddy. With the intercession of Laura Lathrop, who wrote Mrs. Eddy on her behalf, the invitation to visit came, and thus it was that on the day before Christmas, Frau Günther-Peterson and her traveling companion met Mrs. Eddy at her home, Pleasant View.

The two Germans presented her with a gift from the members of the recently established First Church of Christ, Scientist, Hannover: an edition of the Luther Bible, Martin Luther’s landmark translation of the Bible into German (see section below). Mrs. Eddy asked her visitors to tell the donors that the Bible was of greater value to her than its weight in gold.

Recognizing the special needs of the German field, Mrs. Eddy gave Frau Günther-Peterson permission to teach Christian Science, under the condition that she eventually return to take a Normal course under the Christian Science Board of Education. This she did in 1906.

In October 1901, the members of the church in Hannover purchased property on which to construct their own church building. The cornerstone was laid the following April. Dedicated on October 26, 1902, this was the first edifice on the European continent built expressly for holding Christian Science worship services.

Eight years later, in 1910, Mrs. Eddy authorized the translation of Science and Health into German. Three of Frau Günther-Peterson’s students served on the translation committee. Published in 1912, this was the first edition of the Christian Science textbook to be printed in a language other than English.

Bertha Günther-Peterson remained active in Christian Science until her passing in February 1938.

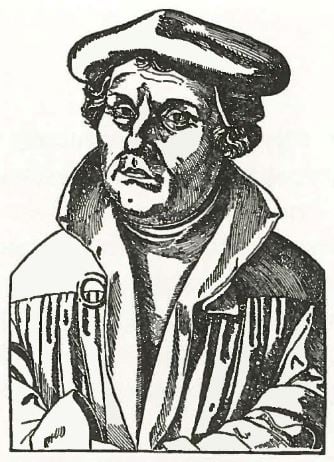

Martin Luther & the German Bible

Mary Baker Eddy was the recipient of two copies of the Luther Bible. The first was presented to her in 1899 by members of First Church of Christ, Scientist, Hannover, Germany; the second, printed in I 733, was a gift from Edward J. Wessels in 1906.

Martin Luther was born in the German province of Saxony in 1483. He studied at the University of Erfurt and in 1505, largely to please his father, embarked upon the study of law. He abandoned it shortly afterward, however, to enter a monastery where he discovered the writings of St. Augustine. He was ordained in 1507. In 1512 he became a doctor of theology and professor of Holy Scripture at the University of Wittenberg, and three years later he was appointed vicar of his order.

Although conscientious in the practice of his religion, he was plagued by fears that he would not be good enough to merit salvation. He found peace in a passage from Paul’s Epistle to the Romans: “The just shall live by faith” (1:17; the Apostle is quoting Habakkuk 2:4; see also Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians 3:11 and the Epistle to the Hebrews 10:38). This passage proved pivotal in Luther’s religious life and teachings.

At the same time, Luther was increasingly troubled by the need for religious reform; indeed, reformation was a major topic of interest in Europe in the early 1500s. In 1517, he challenged the Church’s practice of selling indulgences by posting his Ninety-five Theses upon Indulgences on the door of the castle church at Wittenberg. Written in Latin, the Ninety-five Theses was quickly translated, first into German and then into other languages, and widely circulated, a move made possible by inventions in printing during the previous century.

In January 1521, Luther was excommunicated. Three months later he was called to the imperial Diet of Worms. When asked to recant, he refused, stating:

Unless I am proved wrong by Scriptures or by evident reason, then I am a prisoner in conscience to the Word of God. I cannot retract and I will not retract. To go against the conscience is neither safe nor right. God help me. Amen. [The Reformation, Owen Chadwick, London: Penguin Books, 1972, p. 56.]

Luther’s statement, perhaps with slight embellishment from his close circle of colleagues, became almost proverbial. Mary Baker Eddy included a portion of it as an epigraph of the chapter “Science of Being” in her work Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures — the only epigraph in Science and Health that is not from the Bible.

Luther risked his life by going to Worms, for earlier reformers had been put to death for their beliefs. On his way home, he was captured by a faction friendly to him and taken into hiding for ten months. During this period he began one of his most significant contributions to German culture: the translation of the Bible into German. The Luther Bible not only made it possible for German church-goers to read the Bible in their own language, it also provided the basis for standard German.

Luther spent the rest of his life preaching, publishing and teaching, until his passing in 1546. He shaped the Lutheran denomination and provided for the liturgy to be spoken in German rather than Latin.

He also left his mark in his hymns, which like his Bible were intended for the people. Over sixty translations exist in English alone of his best known hymn, “Ein’ feste Burg [ist unser Gott]” (“A mighty fortress [is our God]”). In the Christian Science Hymnal it is Hymn 10, beginning with the words “All power is given unto our Lord.”

Frances Thurber Seal

In 1896 an American family started on a trip around the world. One of the farewell presents sent to them was a copy of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, by Mary Baker Eddy. After the long journey the wife and children stopped over in Dresden, Germany, for the winter, to enjoy the music and art of that city. During these quiet months the lady studied Science and Health earnestly. She was deeply interested, and talked with those whom she met socially of this wonderful book and the truth it contained.

So begins Frances Thurber Seal’s account of the events that led her to Germany to help establish Christian Science there. The American family which she mentions was that of Mary Beecher Longyear, the founder of Longyear Museum. Although Mrs. Longyear already knew of Christian Science, it was not until she arrived in Germany that she began to study it seriously.

When Mrs. Longyear returned to the United States, she asked Laura Lathrop, then First Reader at Second Church of Christ, Scientist, New York, to send someone to Dresden to introduce Christian Science.

Mrs. Lathrop thought of her student Frances Thurber Seal for this assignment, and sent for her. On the surface, this seems an unusual selection, as Mrs. Seal spoke no German and was a relative newcomer to Christian Science. But as Mrs. Seal explained later, Mrs. Lathrop felt “that this was a call from God, and I was the one to answer it….”

Arrival in Germany

Arriving in Dresden at the end of 1897, Mrs. Seal settled into a small hotel. Her first patients found their way to her, though she as yet knew no one in Europe. As word of healing through Christian Science spread, people of different nationalities and from myriad walks of life sought her out.

Over the course of the next nine years, Mrs. Seal helped to establish a basis for Christian Science in Germany, and was instrumental in the formation of two branch churches: First Church of Christ, Scientist, Dresden, and First Church of Christ, Scientist, Berlin.

In 1898, she returned to the United States for an extended visit. While in Boston, she took the first Normal class offered by the Christian Science Board of Education in January 1899. The Board of Education awarded her a certificate to teach Christian Science and requested her to go to Berlin, the German capital, to establish Christian Science there. She went to Berlin in the summer of that same year and began holding services; classes soon followed. She also assisted less-experienced students in their healing work, and through it all, she carried on a large healing practice of her own.

Freedom to Practice Christian Science

Mrs. Seal had not been in Berlin for a year when she and her students began to experience opposition from certain police authorities hostile to Christian Science. This situation continued for eight months, until Mrs. Seal telegraphed her student Baroness Olga von Beschwitz to come to Berlin. Together they “went to the President of Police, who was a member of the Emperor’s Cabinet”:

He was very gracious until he learned who we were, and then he treated us with utmost contempt, although he could not refuse to hear what we had to say. I told him I was there to tell him what Christian Science was and to satisfy him that we were law-abiding. I stated that it was the religion of Christ Jesus; reminded him that Martin Luther healed the sick through prayer; and told him that Mary Baker Eddy had discovered the scientific method of spiritual healing, and that…we were endeavoring to obey the command of the Master to heal the sick as well as preach the Gospel. Baroness von Beschwitz told him of her experience in being healed of life-long suffering from what was said to be an incurable disease….

When we had explained our position at considerable length, I asked him if we were doing anything contrary to the laws of Germany, and said that if we were, we would immediately cease, as we were above all things a law-abiding people. He seemed greatly enraged, and took up a book which he shook in my face, saying violently, “This is the criminal code of Germany, and there is not a line in it that prohibits anyone from worshipping God in his own way.”

I thanked him and said, “That is all I wish to know, Herr President, and now I have one thing further to tell you, and that is I am not a criminal, but am a citizen of the United States of America, and I shall expect to be so treated in the future.” This closed the interview, and as he had acknowledged there was no law forbidding our Church or the healing work, the police were at once called off, and we had no further trouble along this line. (Christian Science in Germany, Frances Thurber Seal, pp. 66-67.]

At the end of 1906, feeling that her work in Germany was complete, Mrs. Seal returned to the United States to live. She settled in Manhattan, as a practitioner and teacher of Christian Science.

Christian Science in Germany

Its Reprinting and the Longyear Connection

In 1929-1930, Frances Thurber Seal wrote an account of her experiences in Germany. “There must be a score of copies of the manuscript somewhere today,” replied one of Mrs. SeaI’s students, Mary F. Barber, “as it was typed many times, with revisions each time, and given to students and friends.” The story would probably have continued to circulate informally had Mrs. Seal not been encouraged by her students to put it into book form. The resulting Christian Science in Germany was published privately in 1931, publication having been paid for by a fund which one of her students set up for the purpose.

The initial press run of 1,000 copies was exhausted within a few months, even as requests for more copies came pouring in. Negotiations to reissue the book were still pending at the time of Mrs. Seal’s passing at the end of 1932.

A year or so later, most of her files were disposed of, but two boxes of unfilled orders, letters from readers, requests for copies, publishers’ correspondence, other documents and a copy of the 1931 edition were saved by Miss Barber. “My thought was that they might, or might not, be of future interest to someone in some way,” she later explained. Miss Barber was well familiar with the book: as Mrs. Seal’s secretary since the late fall of 1930, she had handled correspondence pertaining to the book when Mrs. Seal departed on a trip to Europe in October 1931. After Mrs. Seal passed on at the end of December the following year, Miss Barber “brought these two boxes home and put them away on a high shelf, and there they remained, unsorted, untouched and largely unthought of, for over 20 years.”

Reissuing Christian Science in Germany

Eventually the copyright on the book expired and was not renewed, so in May 1958 the book came into the public domain. A year passed. One day Miss Barber showed the files which had been saved to another of Mrs. Seal’s students; she was much impressed. “Why don’t you [publish] it yourself?” she suggested.

The original printer was not interested in handling a new edition, and eventually Miss Barber remembered another printer whom she knew slightly. In her account of the reprinting she wrote, “I…went to see him, taking along the original book, the current [issue of The Christian Science] Journal, and about a hundred of the unfilled requests of 30 years earlier. I told him what I could pay down, but that if the book did not sell from the…list which I [had], it might take me a year to complete payment. To my surprise he glanced at only about a dozen of the letters and said promptly, ‘I’II take a chance.’ So we were off, in 1960, with 1,000 copies ordered.”

Neither the printer nor Miss Barber need have worried. “When the book was almost ready,” she continued, “I began sending notices…. Orders poured in, and by the time delivery was made, I had enough to pay the printer in full, and from then on the book paid its own way. I did no other advertising except to lay a re-order form in each book sold retail.”

The book comes to Longyear Museum

In 1977 Miss Barber turned the book over to the Longyear Foundation. Of this decision she wrote:

From 1960 to the fall of 1977 I had distributed about 35,000 copies. Then, my plans being uncertain, I turned the book over to the Longyear Foundation. Several shops had wished to take it over, but I felt these were firms which might change hands or go out of business, and Longyear seemed by far best suited to carry on. Not only because of Mrs. Longyear’s help to Mrs. Seal in the early days,1 but because of their historical interests and greater prospect for continuance as long as demand kept up. A happy solution, which I am sure would have pleased Mrs. Seal.

The slim but arresting volume is still published by Longyear Museum.