Part 1

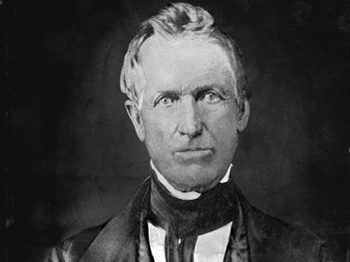

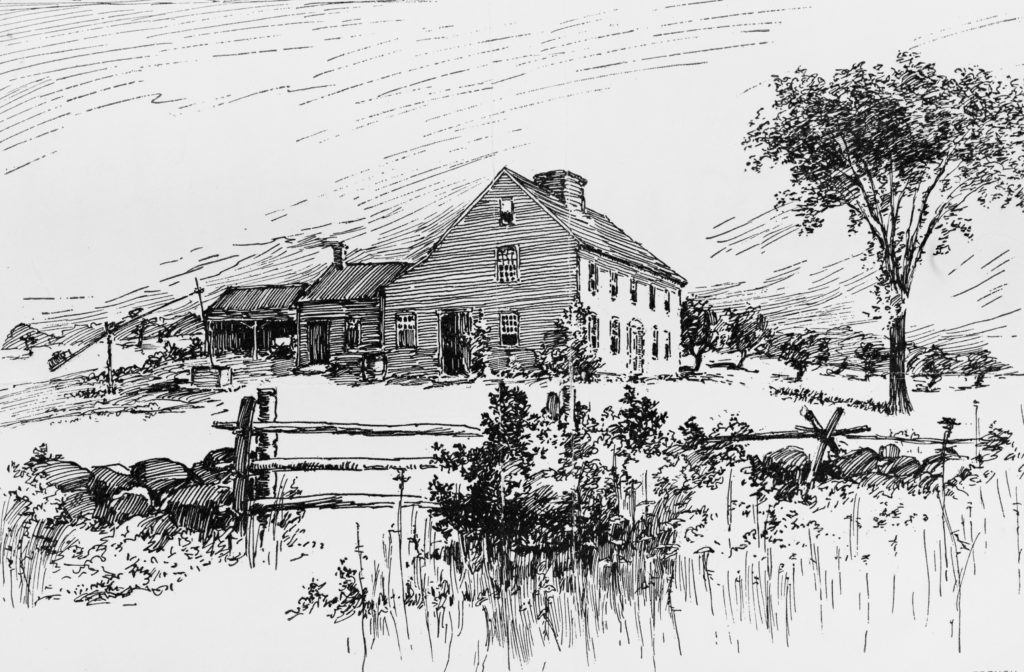

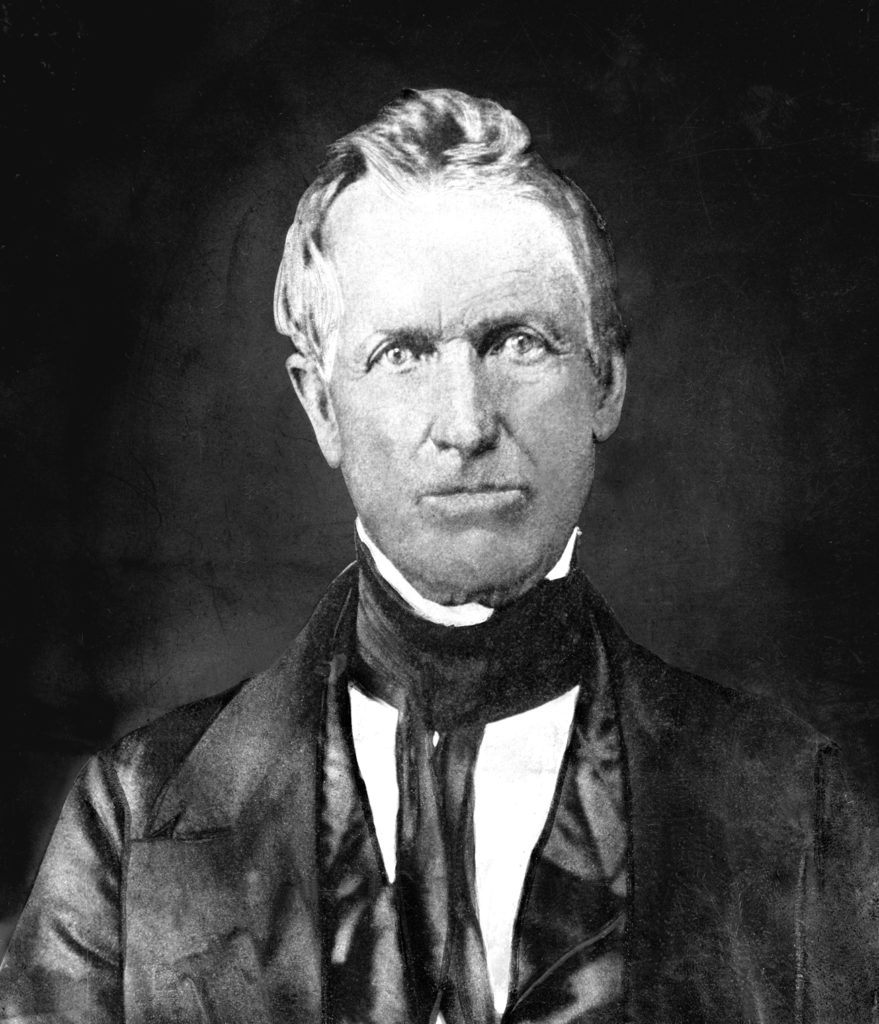

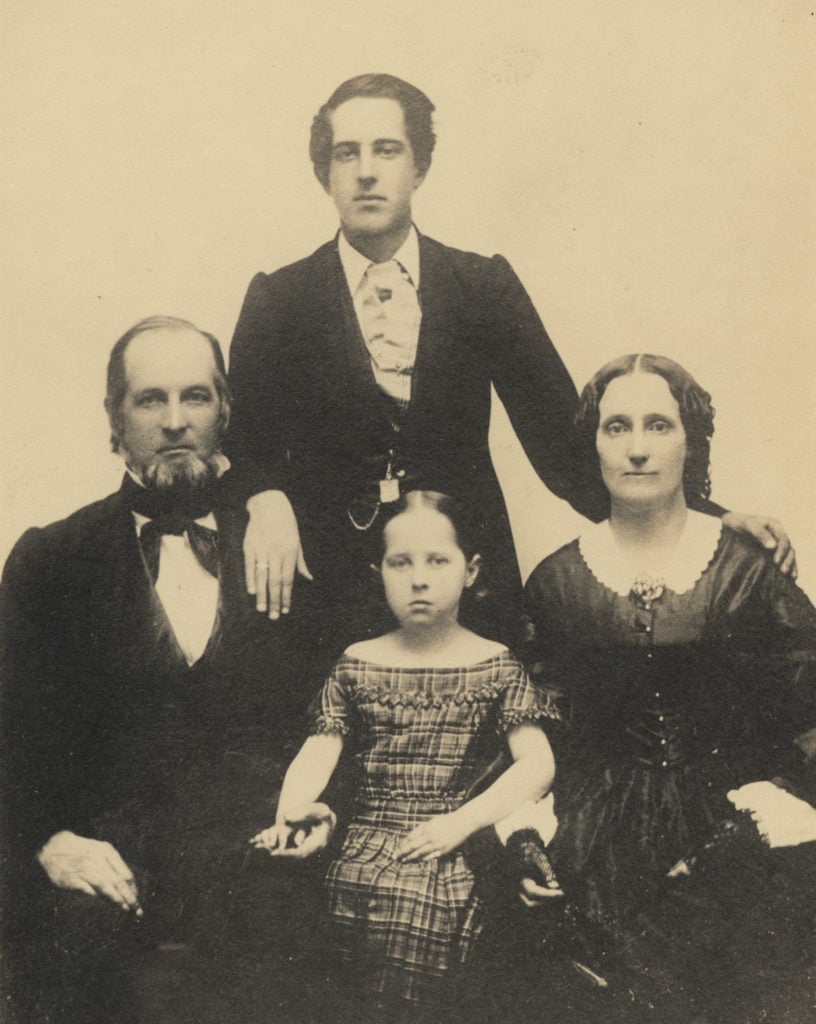

GEORGE SULLIVAN BAKER was the youngest of the three brothers of Mary Baker Eddy. He was nine years her senior and between them were two sisters, Abigail, about three and a half years younger than he, and Martha, a little over six years his junior. By the time George was fourteen—in 1826—his eldest brother Samuel had already left for Boston. Albert, next in line and now sixteen, was a new student at Pembroke Academy on the other side of the Merrimack River which flowed between Bow and Pembroke. Four years later when he went to Dartmouth College, George was still at home, the mainstay of his father on the farm.

The children of Mark and Abigail Baker had a warm affection for one another, but a particularly close relationship developed between the sisters and their brother George during the years spent together at the Bow homestead. Albert, as a student and later as a practicing attorney at Hillsborough kept in touch with his family, whom he dearly loved, but his relationship was that of older brother and counselor. George was witty, resourceful, and responsive, qualities which made him a key figure in the circle at Bow.

Mark Baker had always expected George to remain on the farm, as Mark himself had stayed on the homestead to aid his father, Joseph. But George was a poet and thinker by nature and had no urge toward a trade or profession. While Samuel was learning masonry by experience and Albert was studying to be a lawyer, George had kept his feet in the furrows of the farm—but his eyes were on the horizon.

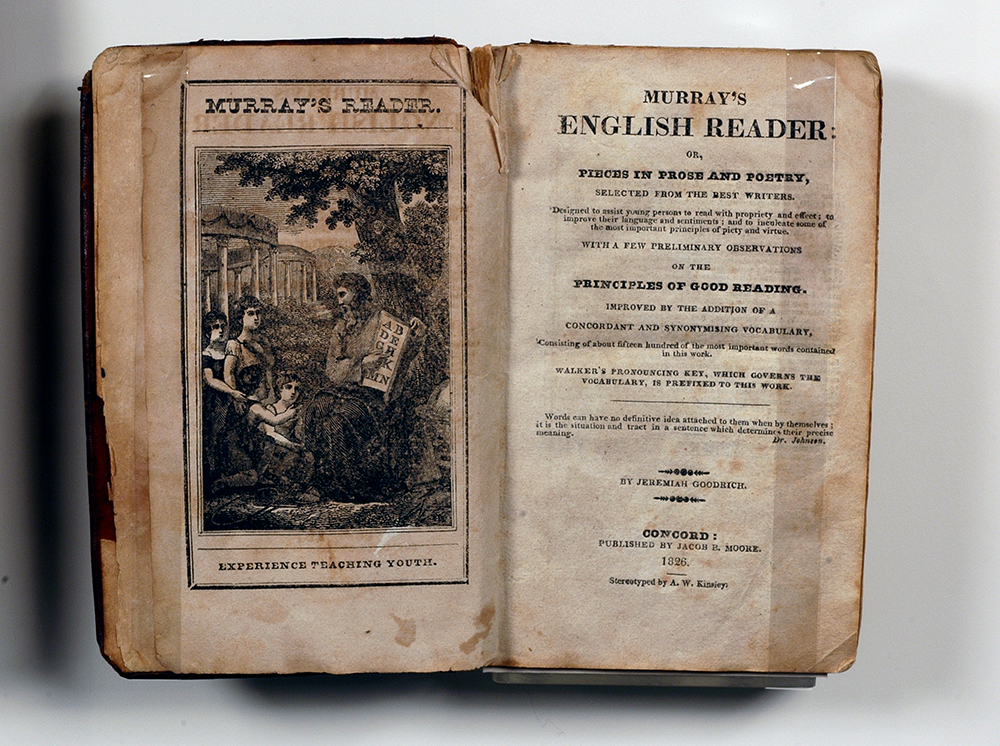

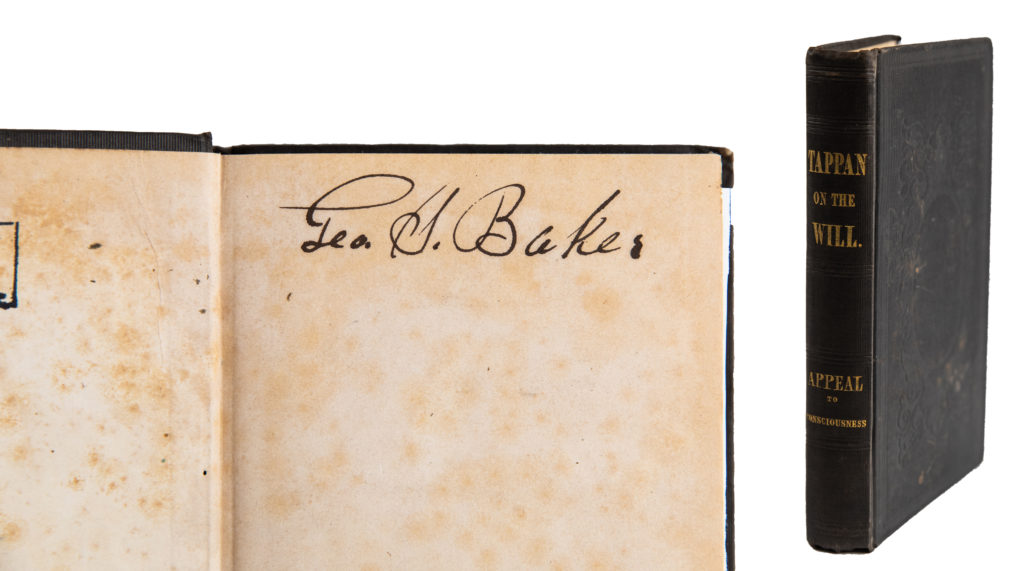

In his early twenties he began to show some ability as a writer. Like all rural children, he had attended the district school. There was good conversation to be heard at home and he had access to good books, which the Baker family always seemed to have, although in limited numbers. But where did he acquire a taste for Shakespeare, and some knowledge of Bulwer and Scott? How did he master a vocabulary ample to express subtle shades of philosophic thought? There may be a clue to his process of learning in a short essay found in his journal that says in part: “The art of living must be accomplish’d as the child acquires a knowledge of orthography, by first learning to spell one word which assists it in acquiring another, and so on until a vocabulary of almost any extent is obtain’d…”

When he was twenty he had charge of a district school at nearby Allenstown, and was invited that same year to accept a similar position at Billerica, which he seems to have refused. But such teaching was off-season employment and did not interfere with the work on the farm, which still loomed large in the plans of his father for him.

At the age of twenty-three, however, George was not only in rebellion against farming as his vocation, but against the religious demands of his father. This, in addition to a poor state of health together with a much-discussed love affair in which he was rejected, seems to have precipitated an impulsive move from Bow in 1835. George fled from the maturing potato crop, leaving it to be harvested by Albert, who was just ending his summer vacation at home. Thus George gained his first freedom from parental jurisdiction.

George went directly to Wethersfield, Connecticut, where a model prison had been built a few years earlier under the direction of Captain Moses Pilsbury and his son Amos. Although George has left no clue as to why he went to Wethersfield, it seems probable that he knew of the important reforms in management made by Captain Pilsbury at the New Hampshire State Prison in Concord from 1818-1829, and of his work at Wethersfield. It seems almost certain, also, that George had met Captain Pilsbury and his family in 1826, when Emily Heath, daughter of the Laban Heaths of Bow and neighbors of the Bakers, was married to Amos Pilsbury. At any rate, he found his first regular employment as overseer of prison shops at Wethersfield, where Amos Pilsbury was Superintendent.

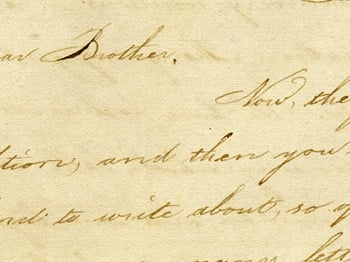

George was unhappy at deserting his father, for whom he had great respect and love despite their innate differences. It was, therefore, a relief when Mary wrote him that his father seemed reconciled to his going. “I think,” she wrote, “from what we have heard him say in the family, and tell others, he was sensible [aware] as well as all of us, the exchange was necessary for your health.” And Abigail, his sister, wrote a little later: “Father has received your information that you cannot return to him this spring. He was disappointed, you may depend, and indeed as we all were, for I should deem your company a special privilege.” In a later letter she mentions pending visits of Sister Eliza, Samuel’s wife, and of Samuel and Albert, adding: “O! do come and see us . . . for we certainly want to see you more than all the rest.” A frequent exchange of letters between George and his family kept him in close touch with their changing life as they moved from Bow to Sanbornton Bridge.

George sent gifts to his family as often as possible. He also contributed to the expenses of the farm in lieu of his own services, and sent money to Martha for her tuition. Martha wrote on October 15, 1837: “Why were you so abundantly prodigal of your gifts? Your too generous heart would, I fear, wrong itself, for the sake of another, but the gift will not be misapplied; and if I do not teach next season, I will attend school.” That this loving concern for his sisters lasted out the years is shown by a letter Martha addressed to George and his wife, Martha Rand, fourteen years later in which she said: “Never—never can I forget your kindness which I do believe was an important means of saving my life, for you not only ‘smoothed the pillow’, but also ‘soothed the mind.'” Meanwhile, Mark Baker continued writing George, consulting him on business matters and offering inducements for him to return to the farm, but added, “You acted your pleasure in going away and so you must in coming back again.” Mark’s letters were always signed, “Your Affectionate Father, Mark Baker.”

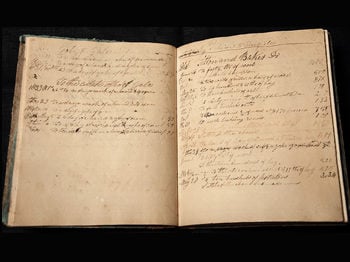

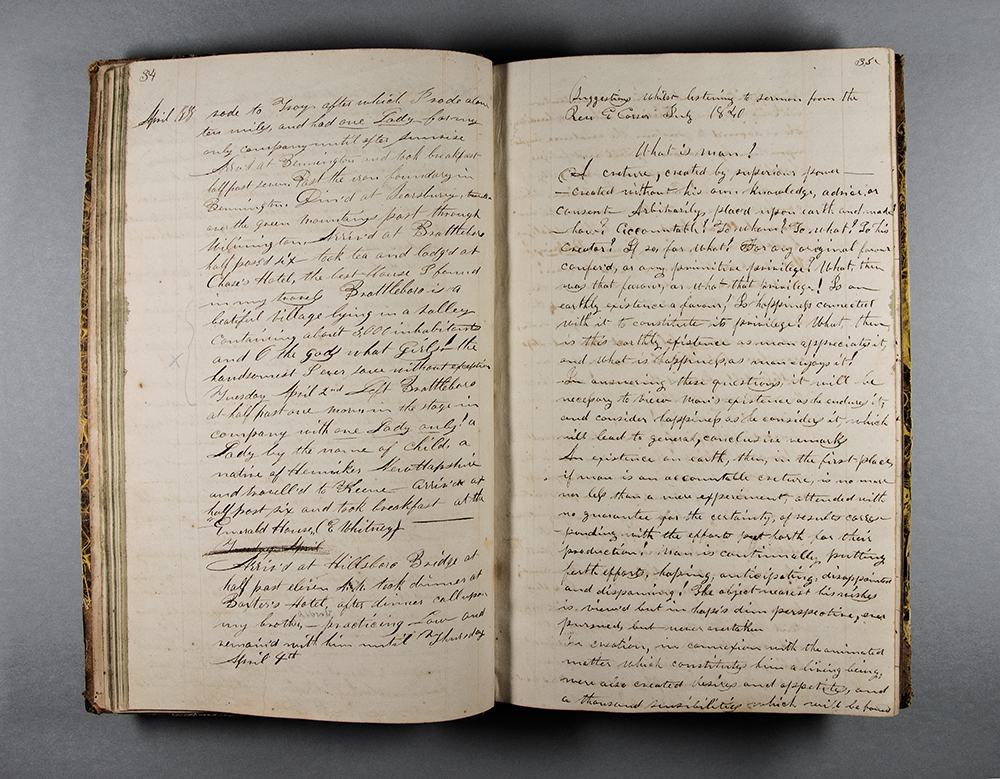

Soon after going to Wethersfield, George began making entries in a journal which continued at scattered intervals from 1836 to 1852. The tides of emotion which swept over him, his moments of gentleness and affection, his appreciation of nature, and especially the misanthropic tinge of his mind, are reflected in these poignant pages written in a firm, legible hand. Here is a man of action and frustration, of friendship and disappointment, of ideals and stark human reality. Sensitive to the stresses and strains of privilege and poverty, of hypocrisy and expediency, he became a seeker throughout life for true friendship. The theme runs throughout his journal. Had he stayed in one field and fought the enemy to a halt, life might have been different for him, but his answer to an inharmonious situation was to move to another field of activity.

Something of his philosophy appears in these lines from a short essay in his journal: “The art of living, or practical philosophy is to let general principles, established by previous resolutions, actuate the mind, guide the desires and direct the effort. . . . Resolutions should never be hastily taken, lest the discovery of errour should properly suggest their abandonment, but when taken correctly, should never be yield’d. Let one general resolution be taken and firmly fix’d in the mind, viz., to do right in all things toward ourselves as well as others. . . . This I conceive to be the philosophy of life which shows the origin of every ill which befalls man to be the result of some error of his own, instead of being an infliction from an offended Deity for original transgression.”

George visited his family in Sanbornton Bridge in September, 1836, about a year after leaving Bow. Back in Wethersfield, he made this entry following his visit:

“Why should I blush that fortune’s frown

Dooms me life’s humbler paths to tread. . . .”

Many of his original entries are signed Gamma, third letter of the Greek alphabet, probably referring to his place as third son in the family. All entries are in his handwriting. One is often in doubt about the authorship of unattributed entries. Each one appears, however, to have some autobiographical implication at the time of entry.

In October, 1838, he wrote: “I have abandoned novels and am reading Shakespeare. For a knowledge of human nature (the great study of my life) I think him preferable to any other author. . . . He shows it in all its naked deformity, as I see it daily practic’d with scarcely one redeeming quality!” The prison atmosphere was indeed a hostile school for such a one as George, searching for an encounter with the ideal.

George grew restive at Wethersfield despite the fact that his work as foreman of the prison shops was giving his employers complete satisfaction. His personal dilemma reaches us in this entry: “What are my prospects? Whilst on one side a delicate constitution and impair’d health enfeebles, on the other, poverty lays her iron grasp.” And on January 27, 1838, he wrote his father: “Honor’d Father . . . Should I return I might find ease from care, anxiety, and suspense . . . but must exchange it for bodily fatigue, which, at present, I cannot endure.” He continued, “I am sick of the business (here), and weary of the place, disgusted with the people, and tir’d almost of life itself. . . . Shakespeare says:

‘The time of life is short

To spend that shortness basely,

‘Twere too long!’

and accordingly I intend to wear, rather than rust out. . . . I resolve to hope nothing, expect little, but exert my utmost to effect something.” Had George been a humanitarian at heart instead of a self-absorbed philosopher, he might have found fulfillment at Wethersfield, where one of the most significant revolutions in prison practices was being perfected under the leadership of Amos Pilsbury.

At about this time, his brother Albert wrote him: “One would think from the style of your letter that all the furies were at work within you, and that you had given vent to your feeling which, like the lava of a volcano, could no longer be smothered. . . . Every day’s experience will teach you more and more the necessity of curbing the impetuosity of your feelings. You are too ardent; you love too hard, and hate too hard. And this honesty of your nature will render you liable to be practiced upon by the designing. Men are not all saints or sinners. No one is so bad but he may sometimes be good, nor so good he may sometimes be bad. Cannot you learn to manage? Manage yourself, I mean, as well as your friends and enemies.”

But Albert’s was a finely-tempered mind, while George’s nature was arresting, spontaneous, and emotional. In any estimate of George, one must view him not only from the standpoint of his inherent nature, but from the rebellious outlook of the time. In the deepest sense he was a 19th-century rebel, of the sort about whom Emerson wrote: ”The key to the period appears to be that the mind has become aware of itself. . . . The young men are born with knives in their brain.” And he sums up the age thus: “Our forefathers had fear of sin and terror of the Day of Judgment . . . followed in this generation by our torment of Unbelief, the Uncertainty of what we ought to do, the Distrust of the value of what we do, and the distrust that the Necessity is fair and beneficent.”

On March 16, 1838, George, at his own request, received his discharge from his services as shop foreman at Wethersfield, Connecticut.

Part 2

ON HIS OWN INITIATIVE, George Sullivan Baker concluded his work as foreman of the Prison Shops at Wethersfield Penitentiary on March 16, 1838. He planned to return to New Hampshire by way of New York, and took passage on the boat Bunkerhill to that city. On arrival, he began a round of walks, visits, and errands, which reveal the variety and character of his interests. George found several friends there who guided his visits and shared the evenings with him.

In his journal, he notes examples of Gothic and Doric architecture, his visit to Niblo’s Garden on Broadway “with its beauties of nature and art,” an antiquarian exhibition with collections of seashells from every land, coins and currency from far and near, noting especially a specimen of old Roman tribute money, weapons of primitive peoples, and other items. He visited the New York Mercantile Library with its 14,000 volumes, making notes about its government and management, operational costs, annual subscriptions, officers, subscribers, and services. Visits to Bowling Green, Castle Garden, Haarlem, reached by rail, and Brooklyn were mentioned. For two evenings, he visited places of entertainment offering plays, circus stunts, dancing, and singing, where he says they were thronged “with those awful creatures, and I ventured to drink a cup of hot coffee with them.” He left New York on the Captain Vanderbilt, travelling up the Hudson past Sing Sing, Point Verplank, West Point, Newburgh, Poughkeepsie, to Albany. After visiting there for a day and taking a side trip to Troy, he took the stagecoach for Bennington and Brattleboro, arriving finally at Hillsborough on April 2, where he spent two days with his brother Albert before going on to Sanbornton Bridge. Numerous close observations on the trip are recorded.

While George had been away from home, many changes had taken place. Abigail had married Alexander H. Tilton, probably the most eligible bachelor in Sanbornton Bridge at the time, in 1837. Mark still hoped George would take over the farm, which he was anxious to rid himself of, but Abigail and Alexander offered another plan. Late in 1838, George and Alexander entered into a partnership asTilton and Baker for the manufacture of cashmeres and tweeds made by a process invented by Alexander. In time, this was to make Alexander a wealthy man and Abigail first lady of Tilton, as Sanbornton Bridge was renamed in 1869. The joint business continued until 1846, when on the sale of the mill building to the Lake Company, George withdrew from the firm, while Alexander continued to operate the plant on a lease basis.

Perhaps George’s proud spirit chafed under the aptitude for management that came so naturally to Alexander, or perhaps he revolted under the routine of business for money, feeling it unworthy of man as he understood him. He recorded these thoughts in his journal: “That human happiness is only a dream, is obvious for many reasons. When I contemplate the narrow limits in which the active and inquiring faculties of man are confin’d—when I see all their powers employ’d in providing their daily bread, and that they have no other view than the support of a miserable existence—I am struck dumb . . . and retire within the confines of my own thoughts . . . the result? I am plunged in a stream of mist and confusion, against the forces of which I cannot contend, but suffer myself, like the rest of the world, to be borne down its current, reckless of the shoals upon which it may cast me.” His cry is like the voice of humanity, reaching out for help beyond itself, a cry which was answered by the Science of the Christ, so soon to be brought to the world by his youngest sister, Mary.

George’s beloved brother Albert, who had been for three years Representative for Hillsborough in the New Hampshire State Legislature, passed on October 17, 1841. As executor of his estate, George was brought in close touch with men of public affairs with whom Albert had been associated. Less than two years later, when a powerful and unscrupulous politician attacked the basic policies of the Liberal Democratic Party and Albert Baker in particular, who had done much to formulate these policies, George stoutly defended his brother’s memory, writing vigorous letters and fiery articles to friends and the press.

In 1844, George Sullivan Baker was made Aide-de-Camp to the Governor of the State of New Hampshire, with the rank of Colonel. Since 1834, he had been Fife Major in the Eleventh Regiment of New Hampshire Militia.

When Mary Baker Glover was returning from Wilmington, North Carolina, to her father’s house after the passing of her husband in 1844, it was George who went to New York to meet and escort her home; and some three years later, in 1847, he took her again on a trip through the White Mountains. In October of that year, he went back to New York, there organizing the George S. Baker & Company, investing much of his capital in an enterprise for operating an entertainment feature, “A Panorama—Voyage Around the World,” shown at 406 Broadway. He was forced to abandon the project at considerable loss early in 1849.

After disposing of his Panorama contract, he sailed on the schooner Camilla Scott, leaving New York on February 21, and arriving in Alexandria, Virginia, after a dramatic thirteen-day voyage graphically described in his journal. He visited Washington, and a few days later went to Baltimore, where on April 5, 1849, he accepted an appointment as Superintendent of the Carding and Spinning Department of the Maryland Penitentiary at an annual salary of $700 plus clothes.

Mother Abigail was always close to George and on August 7, 1849, she wrote: “I felt to mourn and sympathize with you for your loss and disappointment, but remember no one goes deep into business without making some little mistake. . . . I think you have done well and I rejoice that you are freed from that unhealthy dissipated sink of wickedness [New York] and are situated in an elevated beautiful spot in Baltimore. . . . And I am very much pleased with your remarks that your health was perfectly good, and while Favor’d you would never feel to distrust your own resources, and I feel to say without flattery that I never knew a man of such unyielding and unabated resolution as yourself I think myself that you are better off than if you had been on the farm.”

This recalls George’s statement in an essay on “Correspondence as a Source of Enjoyment” in which he said: “I never wish to hear the word ‘Impossible.’ It is the watchword of indolence at her post, and the countersign of cowardice creeping by. If men persuaded themselves it is impossible to raise a pebble even, from the earth, it must remain there. If they are not afraid of Mountains, Mountains must come down. The difficulty does not lie in the greatness of the obstacle so much as in littleness of spirit!”

George took a brief holiday from his work at Baltimore in the autumn of 1849, returning to Sanbornton Bridge, where on November 4, he was married to Martha D. Rand, for whom he had shown great respect and admiration for a number of years. She was also Mary’s choice for him. They were married at the Baker home, where ailing Mother Abigail could attend, shortly before her passing on November 21, 1849. While on the trip to the “White Hills” with Mary in 1847, George had written to his future bride: “Martha, but one circumstance has prevented our enjoyment being complete — the fact you could not enjoy it with us.” And he continued, “Whilst visiting these scenes, one reflection is at all time uppermost — that the God of Nature had selected this region to display His power, and to show man his insignificance . . . and we can but admire and wonder at the incomprehensibility of our own thoughts.”

The marriage was not to prove a happy one. The couple lived in Baltimore until 1852, when George voluntarily left his work at the Maryland Penitentiary early in the year. He took with him letters of warm appreciation from the Monthly Committee of the Prison Board dated March 10, 1852, which noted: “He fully understands his business . . . was faithful and attentive to duties as an officer . . . a gentleman of a good share of intelligence.” He and Martha visited New Berne, North Carolina, taking with them an excellent letter of introduction from Brown and Dunham, importers and jobbers of Baltimore, which stated in part, “Mr. Baker is a gentleman of high integrity and gentlemanly bearing.” But nothing seems to have come of the trip.

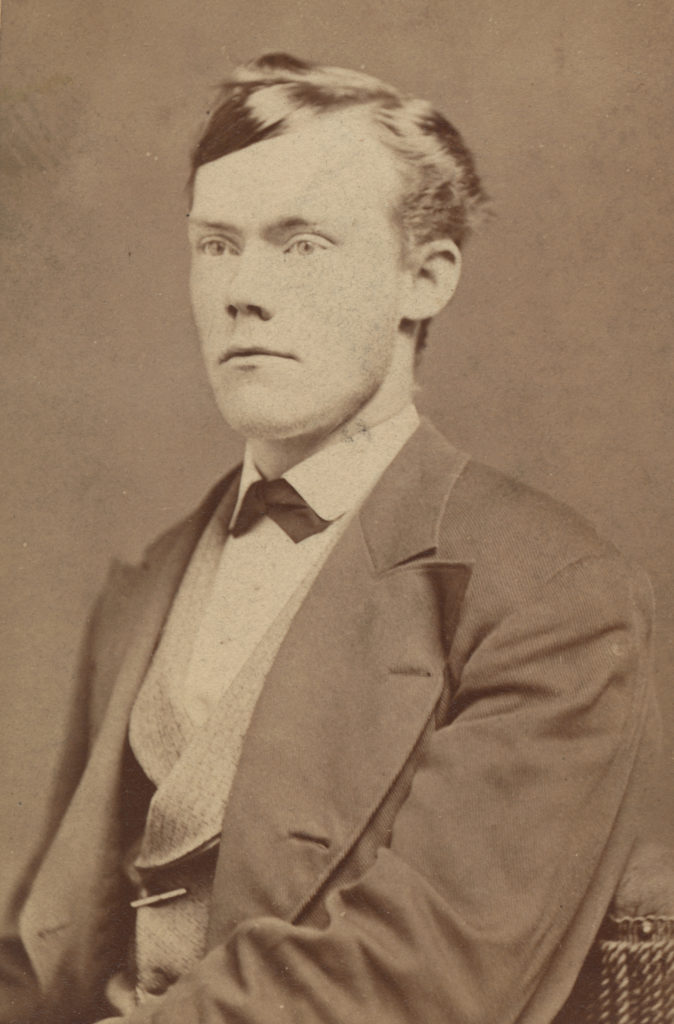

While he searched further for a congenial post, Martha returned to Sanbornton Bridge, where their son was born March 21, 1853. While their relationship over the years is ambiguous, an entry in George’s journal at a later period may well refer to their early experiences.

“We remember the time when I first sought your home,

When a smile, not a word, was the summons to come,

When you called me a friend, til you found with surprise,

That our friendship turned out to be love in disguise

You will think of it — won’t you?

You remember it — don’t you?

Yes, Yes, of all this the remembrance will last

Long after the present fades into the past. . . .”

In 1856, he was back in Sanbornton and nearby Northfield, where Martha’s family lived. He seems to have been employed for a time by the Tilton Mills, but this did not last and he was soon on the move again. Meanwhile, Martha and young George Waldron, as their child was named, continued to live in Sanbornton and Northfield. A strong tie of affection which extended back to her school days united her with the Baker family, and this relationship was to continue throughout the years. The next available record of George shows him to have been employed for a number of years as Superintendent of the Appleton Woolen Factory in Appleton, Wisconsin. Fire destroyed the Appleton plant about 1863, and George made the original draft for the new factory, supervising the rebuilding of it as well as the installation and testing of the new machinery. Although urged to resume his former position, he returned to Sanbornton with Martha, who had joined him in Appleton in 1864.

No records are available to show George’s support of Martha and young George during their years of separation, but it is clear from letters to the family that she was independent and reasonably well cared for. A letter from an Appleton employer throws light on George’s later years: “He superintended the original Appleton Woolen Factory prior to its being burned, with credit to himself and high satisfaction to the proprietors—and also to the many patrons, who purchased the goods. . . . He was a man of temperate and moral habits, and also of business habits and capacity . . . is fully qualified to superintend the manufacture of woolen goods of all kinds.”

Mark Baker passed on at Sanbornton Bridge in 1865, and the second Mrs. Baker, having waived her right to the use of the home, turned it over to George, who was next in line of inheritance. George outlived his father only a little more than two years, and Martha inherited the home after his passing, and continued to live there for more than twenty years.

George’s course was run. How shall one evaluate such a man as George Sullivan Baker? There were moments of genius in his experience when he glimpsed God in His beauty and purity, but he recorded in his journal that, “The cup of life is sweet at the brim, the flavour is impaired as we drink deeper, and the dregs are bitter that we may not struggle when it is taken from our lips.”

Disappointment seemed ever with him. Impatience with oppression and injustice, interference with individual rights as he saw them, and all forms of dishonesty drove him from place to place. Nevertheless, he worked constructively at his post, wherever he chanced to be, yet at heart he remained a rebel against many prevailing practices.

When his sister Mary visited him a few months before he passed on in 1867, he was unable to accept from her the very Truth for which he had so long sought. Mortality seemed to shadow his human experience, but his inner integrity remained untouched and his idealism was in tune with much thinking of the period, which in time led to the reshaping of the old order of his day.

Note

This article was originally published in two parts in the Longyear Quarterly News, Part 1 in Summer 1967 and Part 2 in Autumn 1967.