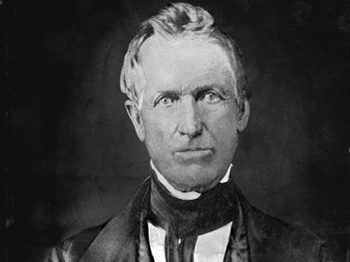

There is protest in America today. Some 130 years ago there was also protest in America. Young people were speaking out, questioning developments of government legislation in this new land. Among them was Albert Baker. He was a young attorney in New Hampshire, the second brother of Mary Baker Eddy. Born February 5, 1810, he followed the signing of the Declaration of Independence by only thirty-four years and the inauguration of our First President by barely twenty-one years.

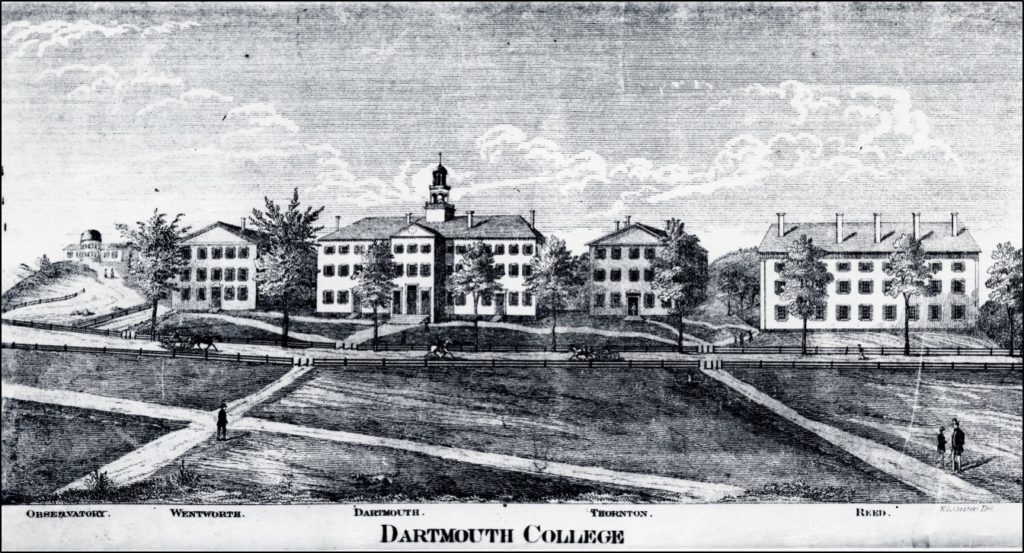

Albert spent the early years of his life at Bow, New Hampshire, on the farm of his father, Mark Baker. The inner urgency that marked all the days of Albert Baker’s life, led him from his youth to seek the things of the mind. He read widely as facilities permitted, and trained himself to think through any subject engaging his interest. At an early age he developed a glowing sense of the new freedom for all men that filled the New England air. The keen interest of his father in religious and political affairs drew to the Baker fireside many of the ablest thinkers in the area, among them Mark’s friend, Governor Benjamin Pierce. Albert was exposed to their lively debates and profited by them as his later college experience showed. At sixteen, he entered Pembroke Academy, just across the Merrimack River from his home. Under the direction of the Principal of the Academy, Hon. John Vose, a Dartmouth man, Albert was prepared for Dartmouth College where he entered at the age of twenty.

Throughout his college career he won highest scholastic honors. He was a member of the United Fraternity, Dartmouth’s debating society, and served it as vice-president, president, and as a critic of debates. In his junior year he was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa Society, winning scholarship honors. His brilliant scholastic career attracted the interest of General Benjamin Pierce, as well as that of the General’s son, Hon. Franklin Pierce, then Speaker of the House of Representatives at Concord and ex-officio member of the Corporation of Dartmouth College. When Albert was graduated in 1834, General Pierce invited him to stay in the Pierce home at Hillsborough, New Hampshire, and to begin the study of law with Franklin Pierce. Although the General met his expenses the first year, we find Albert teaching at the Hillsborough Academy from August to December, 1835, helping himself financially.

The following year he continued reading law with Franklin Pierce but in October he entered the law office of Hon. Richard Fletcher of Boston where he completed his work for his bar examination. He lived with General John McNeil, distinguished for his services in the War of 1812, and Mrs. McNeil, eldest daughter of General Pierce. Albert tutored their children and extant letters to him from this family show their affection and esteem for him. There was also a family connection since General McNeil was a cousin of Albert’s father. On April 19, 1837 he was admitted to the bar by action of the Suffolk County Court of Boston.

After a few weeks spent with his beloved Baker family in Sanbornton Bridge recuperating from a severe illness, he returned in August, 1837 to Hillsborough taking over the legal business of Franklin Pierce, then serving New Hampshire as Senator in Washington. Albert Baker made his home with the aging General and Mrs. Pierce, leaving the Senator free to pursue his political career. Albert kept a watchful eye over these venerable figures until they passed on a few years later, she in 1838, he in 1839.

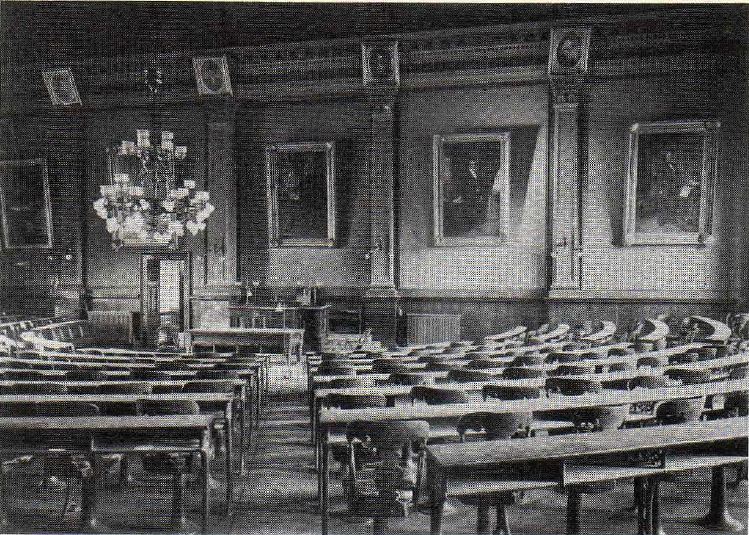

It is not strange that Albert Baker, surrounded by a family so politically motivated, should have elected to enter the field of politics himself. His legal activity expanded rapidly not only because he must settle many unfinished cases of Franklin Pierce’s, but because he himself was soon recognized as one of the ablest lawyers in the area. He gave generously of his time to the Hillsborough community, serving from 1837 as Justice of the Peace on a five-year term. He was Librarian of the Hillsborough Social Library, a forerunner of the Carnegie Public Library, and was one of a committee of three appointed to superintend the prudential affairs of the several schools in Hillsborough. In 1841 he was appointed Moderator of the annual Town Meeting. About a year earlier he organized the Jacob R. Whittemore Association of Literary Advancement, an affiliate of the National Society of Literature and Science. Three times he was elected State Representative from Hillsborough County, serving from 1839 to the time of his passing on October 17, 1841 at the age of thirty-one. He spoke freely in Representatives Hall, commanding respect for his ideas and convictions. Among important committees to which he was appointed were the Committee on Slavery of which he was chairman; the Committee to Draft Resolutions; and a special Judiciary Committee for which he presented a report to the House. While in Concord at the Legislature his legal business made many demands on him which he often met in the office of Pierce and Fowler, established by Franklin Pierce in 1838, on the second floor of what is now the Christian Mutual Life Insurance Building.

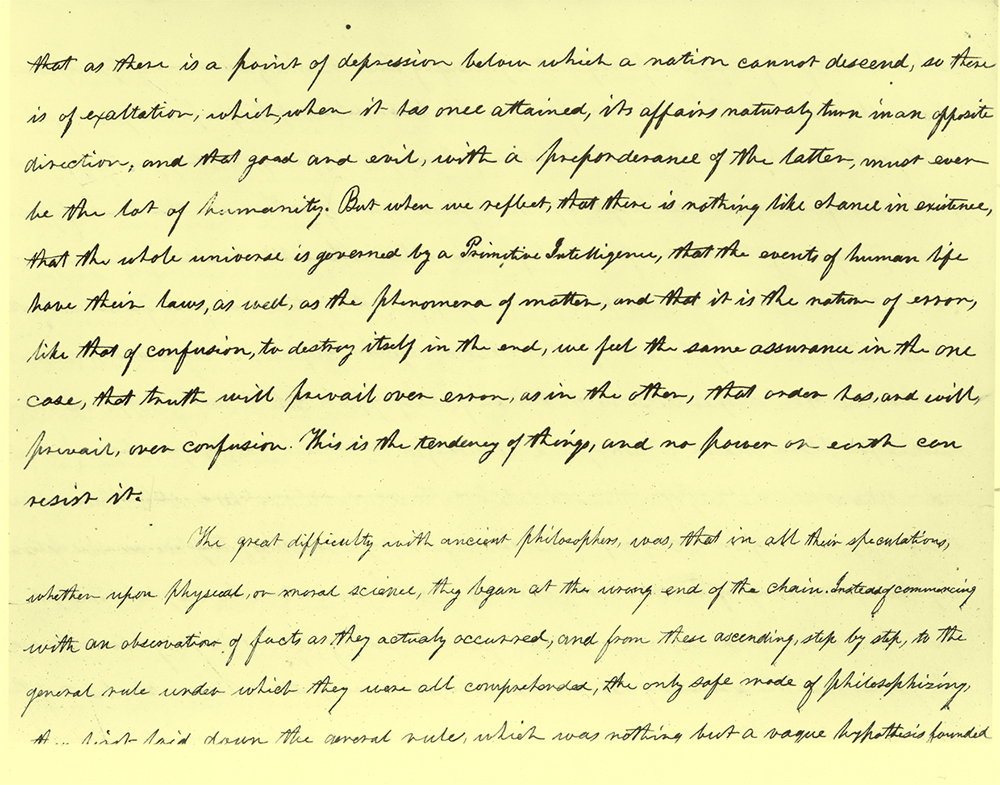

In a few short years he became virtually the leader of the Democratic Young Men of New Hampshire and organized a chapter of the Association in Hillsborough. He was called upon to address many meetings — the Bay State Association of Democratic Young Men, similar groups in Andover and Hillsborough, a July Fourth Rally, a Jackson Day Celebration, and others. “Our country presents at this moment,” he said, “a most extraordinary spectacle. Never since the Revolution, has there been seen and felt a commotion like that which now pervades society… Through the length and breadth of this Union…all classes, all ranks of society, partake of its influence.” Fortunately the manuscripts of many of Albert Baker’s addresses in his own handwriting are now preserved in the Baker Collection at Longyear Foundation. In reading these impassioned speeches, there is no doubt that Albert Baker saw clearly “the establishment of this nation under God as the great discovery of the present age.”

“Herein lies the secret of the Declaration of Independence,” Albert Baker said to a Fourth of July audience, “Not, that it gave existence to a nation, but, that it declared those great, living, eternal truths, upon which rest the liberties of the human race. A few plain propositions, uttered in the most simple and artless language, yet [they are] of more importance to man, of more influence upon his destinies, than all the political truths that were ever-proclaimed since the world began… Let us teach those that are to come after us,” he urged, “to cherish with all the love, and gratitude, and affection the recollection of a day, which, next to that on which the Son of man rose from the grave, is destined more deeply to affect the interests of the human race.”

“Through the long lapse of ages,” he continued, “man has groped his way in political darkness. Here and there upon some favored spot, has the beaconfire of liberty thrown up a fitful glare… It flashed upon the earth and went out… Why was it thus? Because man knew not his rights; knew not his powers, his capacities, knew not the end for which he was created… The great fundamental truth of the natural equality of mankind, had remained a secret, as well to the wise, and the prudent, as to the ignorant… [They] had not dreamed of the sublime truth upon which rests the whole fabric of human liberty, that He who created man, had no respect to persons; that He had created all in the same image…each upon an equality with the other; not an equality of physical strength, or intellectual endowment, but an equality in the participation of political and civil rights; an equality in the enjoyment of all the privileges and immunities, that distinguish the freeman from the slave.”

“Clad in the panoply of a righteous cause, with their own conscience and the world to bear testimony to the rectitude of the motives by which they were actuated, our forefathers went forth fearlessly. With the smiles of a benign Providence, they went forth triumphantly.”

He held that the theory of our government, both state and national, is that of entire freedom, “in as much as it acknowledges the inherent right of the people to ordain, change, or abrogate laws by which they consent to be governed, according to their good will or pleasure. These are the principles, this is the spirit, of the Declaration of Independence…the great charter of our liberties.”

It was with something close to prophetic vision that he declared: “The power of the Declaration of Independence is as enduring as the promises of God, power that will be felt through all time, and in the remotest extremity of the earth… Here is the pivot on which will turn revolutions that will hereafter shake the earth to its center.”

In Albert Baker’s day many people looked with disdain on the common man and his abilities to govern himself. They feared popular government as a threat of anarchy, possibly another French revolution. His answer, “Let that stand as it does, a lasting monument of the extravagance of oppressed and infuriated men, a beacon to warn the steps of other generations. But because I condemn the enormities of that period, let it not be supposed that I pass sentence against the principle for which the people contended, the right of self-government.”

In a fearless speech to the Bay State Association of Democratic Young Men at Boston on February 3, 1840 Albert Baker declared, “The Constitutions of the American Republick, the grand achievement of the age in which we live, furnish the only instance in which the rights of man, as man, unaided by the extrinsic circumstances of birth, or condition, are acknowledged… But let it not be supposed that nothing remains to be done. The attainment at this point, is nothing but the raising of the power. The application is yet to be made.”

“Wherein then is the difficulty?” Baker asked, and answered, “Liberty has found an abode in the earth… But its fruits have been well-nigh lost. The people have permitted those to whom they have entrusted the duties of legislation, to enact laws, not to secure liberty…but to aggrandize those to whose interests are adverse to theirs, whose first, whose last effort has been to break down and control the ascendency of the people.” He resisted the growth of corporations as leading to an aristocracy of wealth and privilege, controlling the affairs of the nation. He denounced the management of the currency as interfering with trade, upsetting the natural equilibrium of money and the law of supply and demand.

“The aristocratic principle was never more firmly established in England…than it will be here, when you will have gone on and completed what is already commenced… Place the wealth of the nation in the hands of corporations; give to your bankers the monopoly of the currencies…make the yeomanry hewers of wood and drawers of water for so much a day as their kind masters may see fit to give them; and what will be left of liberty? …Our struggle is to decide whether associated wealth or individual suffrage shall rule our land.” He deplored the loss of judgment and integrity that accompanied the granting of special privileges by a government designed for all the people.

He would restrict the legislative powers of government, he told them, and seek a way in which the industry of man would never be shackled; when each person should employ himself “as nature and condition have furnished facilities.”

The Boston Post of February 5, 1840 gave a generous review of the Baker speech saying in part, “The rapt and devoted attention with which the audience listened to Mr. Baker’s clear and animated reasoning adorned as it was with witty remarks and classical allusions was a far greater tribute to his powers of mind than the most enthusiastic applause which ever followed these periods of calmness… The lecture was one of the most sound and eloquent political discourses which has been delivered before this Association since its establishment…clothed in language which, while distinguished for its critical correctness, was comprehensible to all who listened to it, the uneducated as well as the educated.”

The reviewer further associated Albert Baker’s name with those of Governor Isaac Hill and Hon. Henry Hibbard, as one of a “glorious triumvirate” including “experience of age, ripened manhood, and the fervor, ingeniousness, and active intellect of youth.” It seems that Albert Baker had agreed he would run for Congress in 1843, but no conclusive evidence remains to substantiate this plan. Representative Edmund Burke wrote George S. Baker from Washington after the passing of Albert, “Your brother was a young man of high promise.’ His clear and powerful intellect, united with stern integrity of purpose, and his fearless untiring perseverance, had made him a favorite of the Democracy of New Hampshire, and if he had lived, would have secured ultimately the highest honors which their gratitude could bestow.” A number of letters to him on the question of abolition from John C. Calhoun and a letter of introduction to President Van Buren leave no doubt of his promise for a national political career.

Albert Baker’s impassioned recognition of America’s place in world history may well bring inspiration to many of the twentieth century. He did not concern himself with the wealth of America, her power, or even her standard of living except as it affected the progress of man. His concern was the resurrection of men, and the realization of their full capacities under a government of free men under God. This is still the potent goal of today.

“By making the errors of the past our beacons for the future, by a full development of the democratic principle, and by unceasing vigilance in guarding our rights, the superstructure of our political edifice will equal the base in beauty and solidity.”

Albert Baker

Surely here in her beloved brother Albert can be found one of the strong influences in the liberation and awakening of Mary Baker Eddy who has given the world the true way to liberty for all mankind.