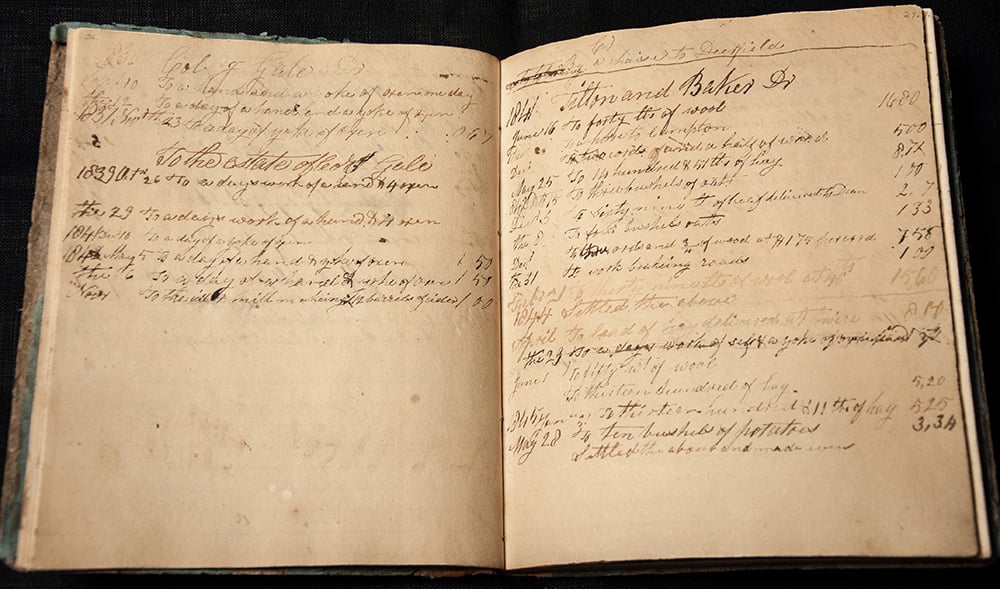

The ink is faded, the blue cloth cover weathered by use and age. In an exhibit full of artifacts related to the life and work of Mary Baker Eddy, this unassuming ledger book could easily be overlooked, and in fact, the information preserved inside its 80 delicate pages has been explored by few over the years.1 Venturing into this early material, however, reveals a treasure trove of valuable insights into the man who raised Mrs. Eddy — her father, Mark Baker.

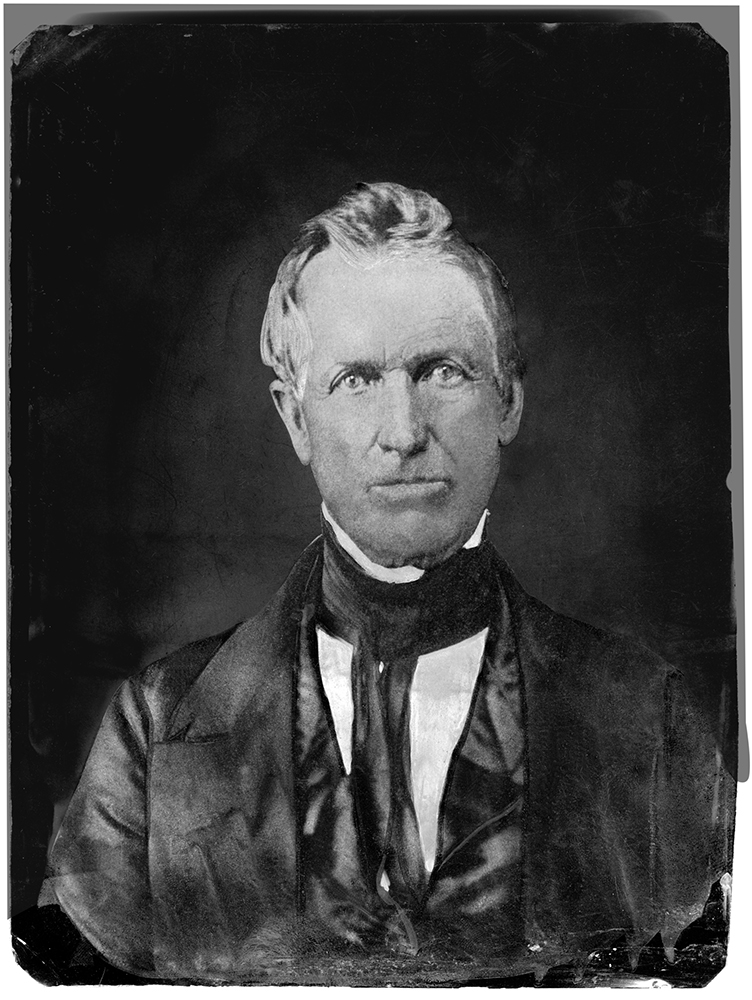

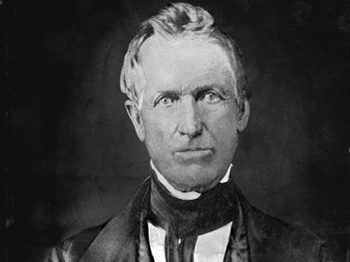

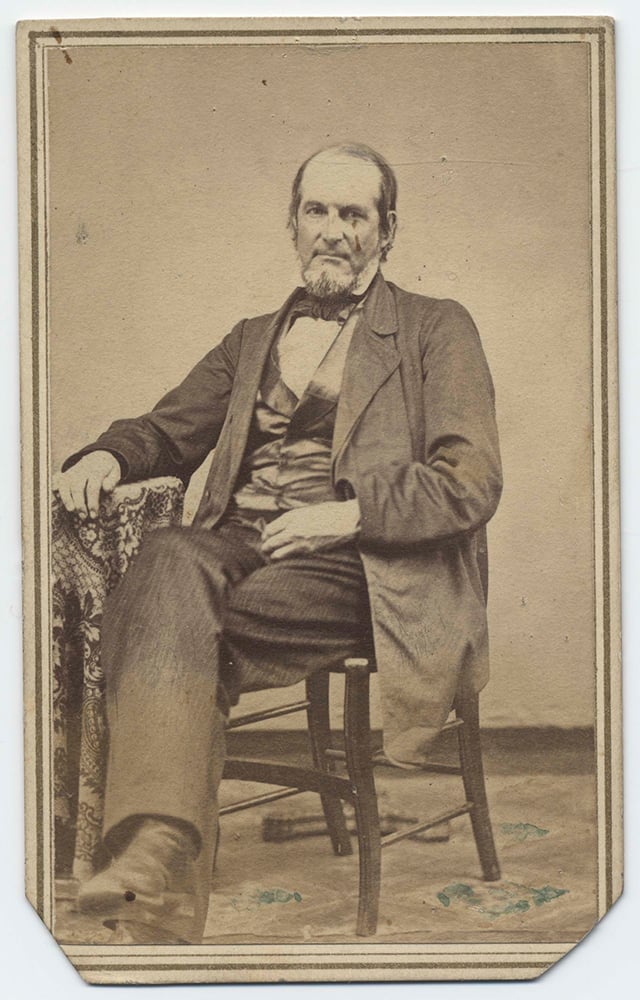

Mark Baker, the man, strides down the corridor of history clothed in familiar garb: stern but affectionate father, hardworking farmer, unwavering Christian. “He was a man of strong character, highly respected in the community, whose opinion was sought and valued,” Gardner S. Abbott once observed. Abbott, who was clerk of the Congregational Church in Tilton, New Hampshire, also noted that Mr. Baker “was very much of a gentleman, well-read, a good talker, and expressed himself clearly and forcibly. And he treated all men with kindness and respect.”2

As the head of his family, Mark was a major influence in his daughter Mary’s life: he raised her and her five siblings to adulthood, and he continued to help support her after the death of her first husband. While he never lived to see his youngest daughter become the leader of a worldwide religious movement, without a doubt he made a deep impression upon her — and in some ways upon her later students, too. Workers in Mrs. Eddy’s household at Chestnut Hill would recall the anecdotes she shared about her father, stories that illustrated his morals, his sense of civic duty, his religious conviction — even his sense of humor.

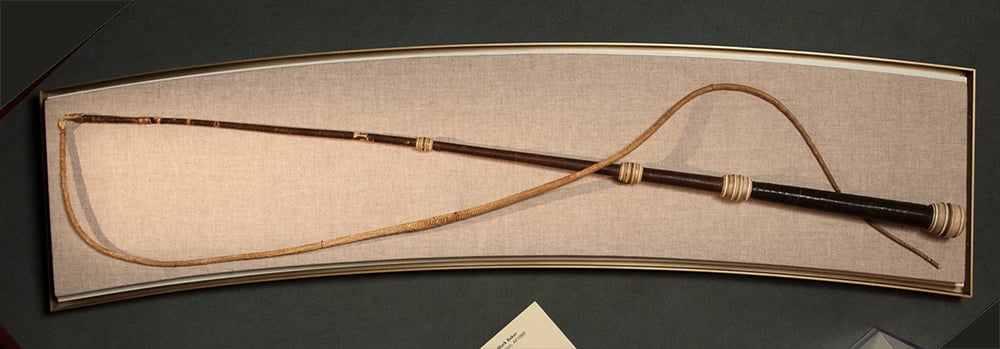

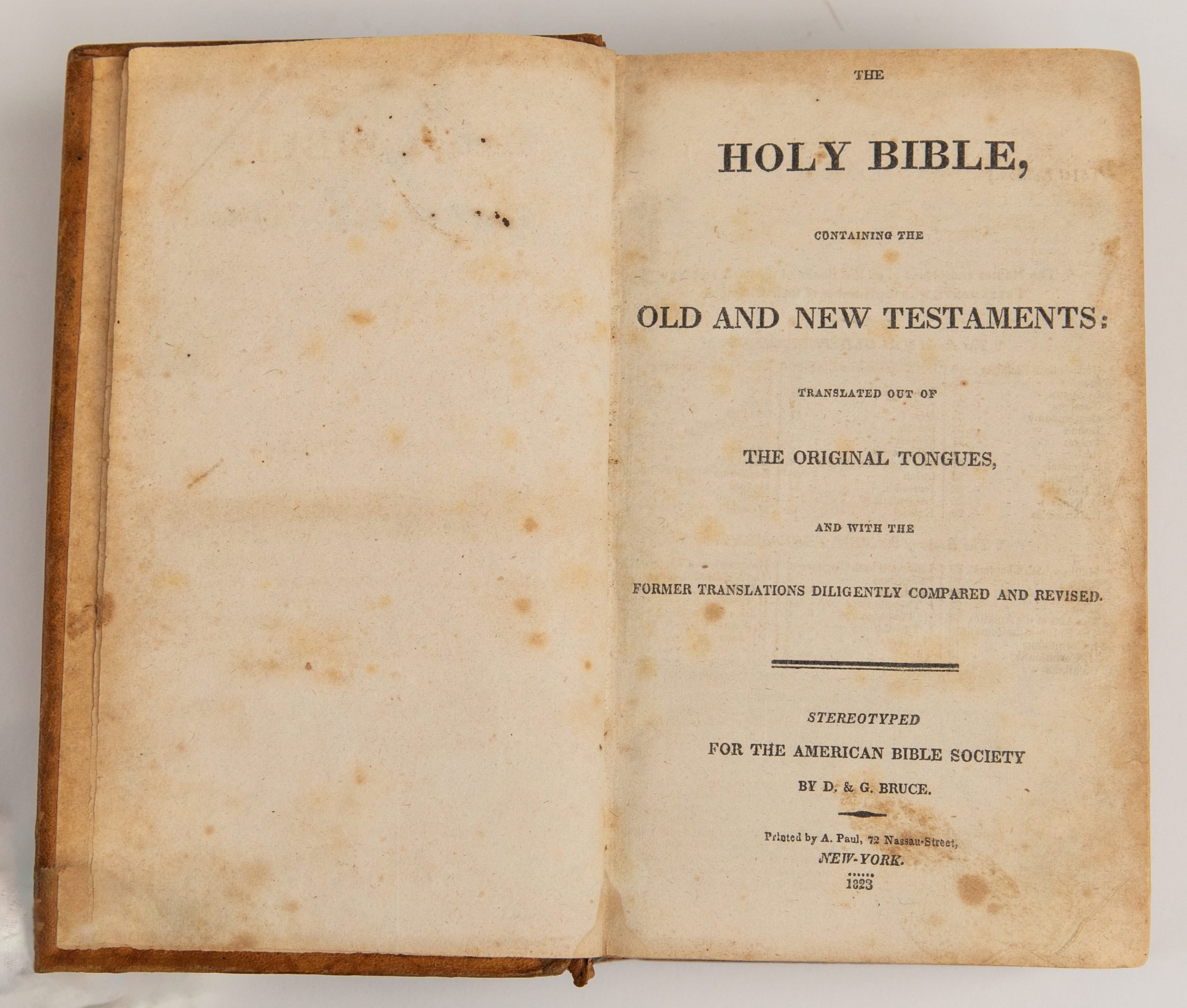

Much of what is known about Mark comes from anecdotes like these, as well as from the Baker Family Collection at Longyear Museum. Documents, correspondence, and even some possessions help form a portrait of the man. So, too, does the ledger. Under its cloak of names and numbers lie forgotten details about Mark’s community, his activities, his network of relationships, and even clues to his financial state over a period of 25 years.

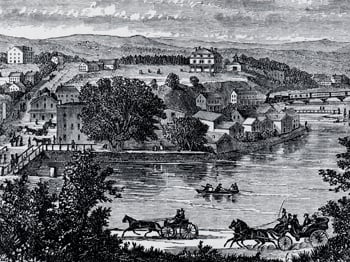

A Close-knit Community

The ledger is an account book, one listing goods sold and services rendered by Mark to others. Nearly 500 entries are recorded under the 54 different accounts — the first in 1829 and the last in 1855. Some of the names of Mark’s customers are familiar; others are not. There is Alexander Tilton, for instance, Mark’s son-in-law, and Aaron Baker, his nephew. But who are Col. J. Gale and Dr. Enos Hoyt? Some names appear only once; others more often. To some degree, however, every name expands what is known about the New Hampshire communities in which the Bakers lived. And when these names are cross-referenced using today’s research tools, interesting connections come to light.

For instance, while the Bakers were living in Bow, Eliza Whittemore Baker was one of Mark’s best customers. Eliza was the daughter of Mark’s older brother, Daniel, and when she was around 25 years old, she began purchasing items (mostly potatoes and wood) from her uncle. Their business relationship continued for a few years but abruptly ended on October 4, 1832, after she purchased a quarter pound of butter. The ledger reveals no more, but a likely explanation is found in records from the Congregational Church in Concord: just seven days later, Eliza married a fellow from Massachusetts. The butter was perhaps even used for the special occasion!3

Another major account from the Bow years is that of Capt. Andrew Gault. The ledger shows that Mark usually helped Andrew on his farm during the month of April. In return, Gault reciprocated on occasion at the Baker farm and also provided Mark with barrels of cider.4 These are interesting details about a relationship that actually went far beyond business.

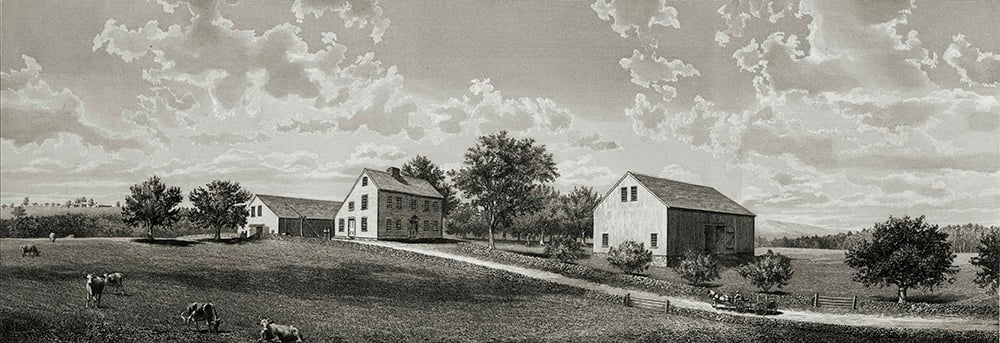

Andrew, who was a few years older than Mark, lived with his family just south of the Baker farm. A dirt path connected their properties. Their families were quite close. Andrew and Mark served together as Bow’s coroners, their wives were close friends, and their children grew up together.5 In fact, one of Mrs. Eddy’s earliest extant poems is dedicated to Andrew Gault, Jr. When the Bakers moved away to Sanbornton Bridge in 1836, the ledger shows that Mark’s business with Andrew came to an end, but letters and documents prove the friendship between the two families continued for decades.

In Sanbornton Bridge, Mark set about establishing new business relationships. One prolific customer in those first years was William Hayes, who accounts for 20 transactions from 1836 to 1837. Mark apparently performed a number of farming tasks for him. The Hayes name turns up again in correspondence and in other documents,6 and from these it is clear that William Hayes and his family were the Bakers’ neighbors, and that their relationship, just as with the Gaults, extended beyond farm work. Letters in particular add colorful details. During the week of Christmas in 1836, for instance, 15-year-old Mary Baker tells her brother George about attending a party for ladies at Miss Hayes’. She teases him that he should no longer worry about Miss Hayes’ unwanted affections because she is at last betrothed!7

There are many more names of interest in the ledger, but perhaps the most significant belongs to Alexander H. Tilton, the wealthy and successful manufacturer who married Mark’s oldest daughter, Abigail, in 1837. Their business relationship lasted from 1839 to 1855, and 35 transactions are recorded under Tilton’s account, making it the fourth-largest in the ledger. Mark seems mostly to have done farm work for his son-in-law, but he also sold him hay, veal, and other miscellaneous goods.

Interestingly, an additional 23 transactions show up under an account labeled “Tilton & Baker.” This is in reference to a joint venture begun in 1838 between Alexander and Mark’s son George. The two operated a mill that manufactured kerseymeres, or fine woolen fabrics, using a process invented by Alexander.8 Beginning in 1839, Mark sold them a variety of goods and services, including wool for their mill. George ended up backing out of the business in 1846, and while Alexander continued with it, the ledger shows that Mark’s involvement also ended in June of that year.

An abundance of interesting links tie the ledger’s accounts together, spotlighting the inter-connectedness of the community in which Mark Baker lived. In addition to his business with his son and son-in-law, there are accounts for his nephew Aaron and niece Eliza — and for his brother Philip, who moved from Bow to Sanbornton Bridge, too. Mark did business with John Curry, who served as a trustee of the local school along with another customer, Dr. Ladd; with Hazen Cross and Enos Hoyt, who both once sang in the choir at the church the Baker family attended; with his neighbor Benjamin Colby, whose son served with Mark on the Park Cemetery Association, along with the tailor Rufus Bartlett and the carpenter Lowell Lang. This rich tapestry of names woven throughout the ledger shows that Mark did business with family members, neighbors, and friends — essentially all those around him, which is not altogether surprising but underscores the close-knit nature of his community.9