This article was written in observance of April as National Poetry Month in the United States.

“Oh, you have put my pink roses on my poems.”1

Mary Baker Eddy’s face lit up as William Dana Orcutt, head of the University Press in Cambridge, Massachusetts, placed a slim volume in her hands.

Earlier that spring of 1910, the press had been commissioned to create a collection of some of Mrs. Eddy’s poems, and recalling her fondness for pink roses, Orcutt asked the artist to incorporate them into the book’s design. Bound in white, the cover of the sample volume he’d brought to show her bore an elegant floral motif stamped in green and pink and gold.2 Inside, mocked-up pages in a substantial cream stock showed off the attractive typeface, and a layout that would include an illuminated capital letter intertwined with more roses at the beginning of each poem.

In addition to her obvious delight with the book’s design, Mrs. Eddy displayed another emotion that day which Orcutt had never seen in their nearly two decades of working together: a hint of shyness.

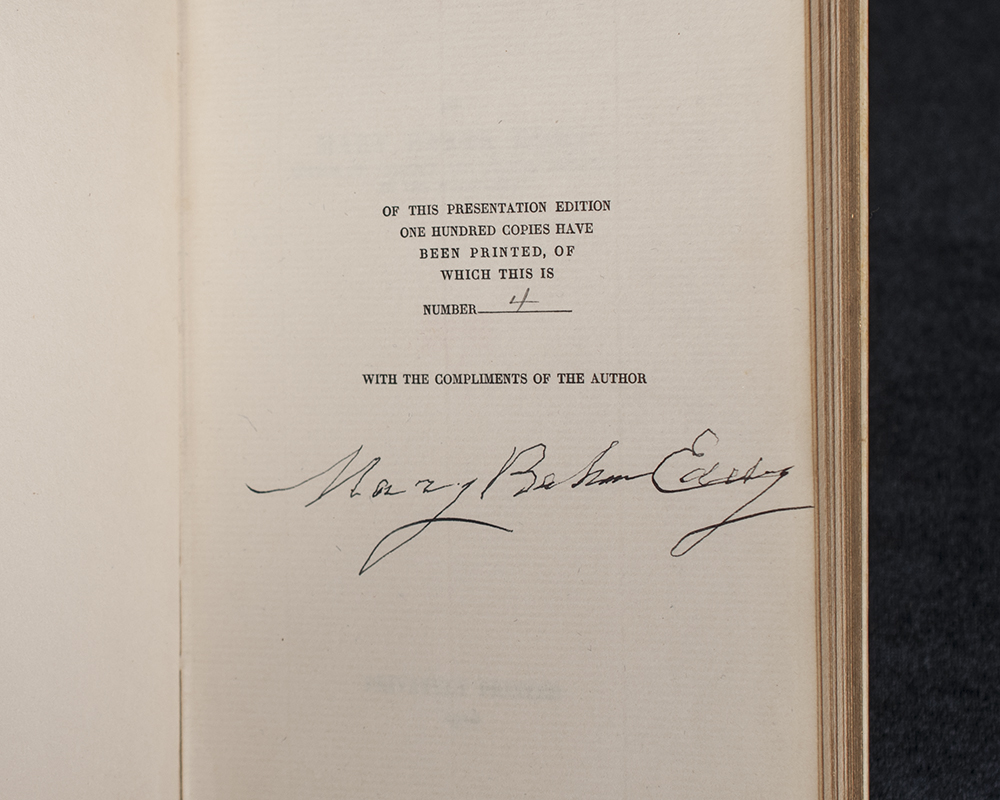

“Somehow poems seem more personal than prose,” she told him as they discussed publication plans.3 The original intent had been a 100-copy presentation edition for private distribution, but Mrs. Eddy was being encouraged by her staff to approve another edition for the general public.

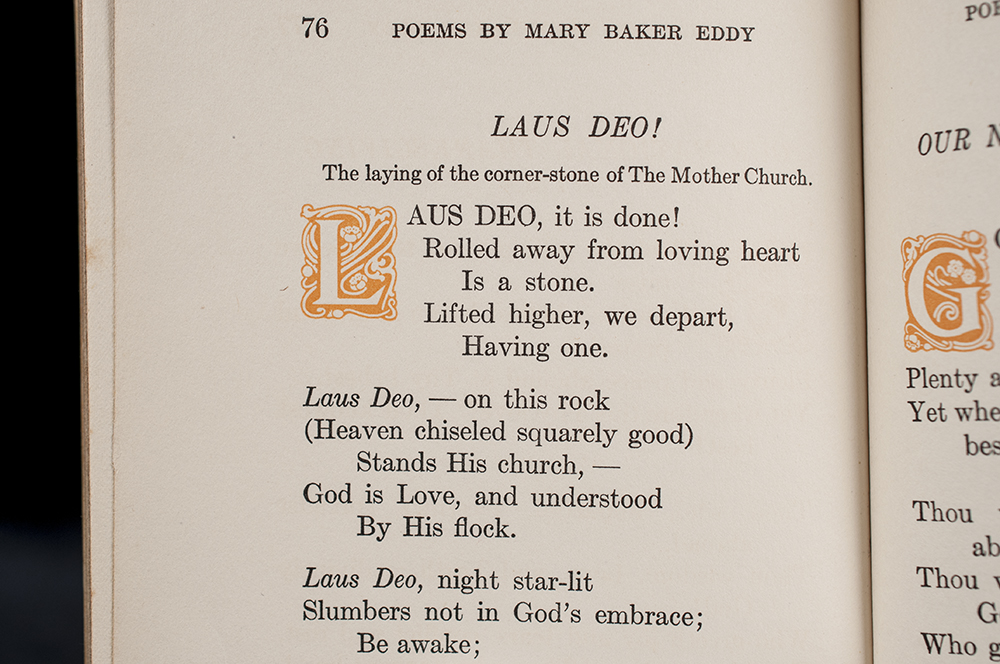

As a collection of what Adam Dickey would describe in the book’s forward as “the spontaneous outpouring of a deeply poetic nature,”4 the volume that Mrs. Eddy held in her hands was personal—as much so as an album of candid snapshots. The poems spanned nearly her whole life, stretching back to girlhood with such early efforts as “Autumn” and “Resolutions for the Day.” They touched on moments both public and private, triumphant and tender—“Laus Deo!” was written to mark the laying of the cornerstone of The Mother Church in 1894, for instance,5 while “I’m Sitting Alone,” written in the fall of 1866, reveals the depth of loneliness she felt as a young woman missing her mother, her first husband, and her young son.6 Some of the poems had been published in newspapers and magazines; others had appeared in the Christian Science periodicals.

Before Mrs. Eddy could decide whether or not to approve a general edition, though, she had work to do. As Orcutt watched, she reached for her pencil and began to edit.

Poetry had always come naturally to Mary Baker Eddy. In fact, she told one of her secretaries that as a child “it was easier for me to write in poetry than in prose,” and that she even wrote some school compositions in verse.7 To another household worker she recalled writing “Mother’s Evening Prayer,” one of seven of her poems which would later be set to music as hymns, “without conscious effort, the words slipping off her pen fast as she could form them.”8

If Mrs. Eddy wrote poetry with ease, the end result nevertheless came under the same close scrutiny as her prose. Just as with Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures and her other writings, she expended much effort in editing and revising her poems, always striving to clarify her message.

“Mother’s Evening Prayer,” for instance, originally ended with the phrase “mother finds her home and far-off rest.” At one point, Mrs. Eddy changed the final words to “heavenly rest,” and asked Mr. Dickey what he thought of the change.

“I told her that to me it conveyed a much better thought,” he recalled. “I said that ‘her home and far-off rest’ carried the impression that she had a long and toilsome way ahead of her.”

“That is just the thing I want to get rid of,” Mrs. Eddy replied.9

“Christ My Refuge,” another of her poems that would become a hymn, was first published in the Lynn Reporter in February of 1868. Mrs. Eddy would return to these verses again and again over the next 40 years, making both major and minor revisions. The final edit occurred in 1909, when she changed the last stanza of the third verse from “I kiss the cross, and wait to know a world more bright” to “I kiss the cross, and wake to know a world more bright.” Just one word, but what a world of difference!

During their meeting at Chestnut Hill that day in 1910, Orcutt witnessed this same attention to detail as Mrs. Eddy took her editing pencil to one of the poems in the mocked-up volume, focusing on the first verse of “Meeting of My Departed Mother and Husband,” which at that point read:

Joy for thee, happy friend! thy bark is past

The dangerous sea, and safely moored at last –

Beyond rough foam.

Soft gales celestial, in sweet music bore—

Mortal emancipate for this far shore—

Thee to thy home.

As Orcutt recalls, Mrs. Eddy read the verse aloud twice, emphasizing the next to the last line.

“Mortal is not the right word,” she concluded, and with a decisive swipe of her pencil she changed the phrase to read “Spirit emancipate for this far shore.”10

In the end, Mrs. Eddy gave her consent to publish both editions of the poetry collection. The presentation edition of Poems was printed in September of 1910, while notices in the Christian Science Sentinel and Journal later that fall announced an edition for the general public, cherishing the hope that “the opportunity now presented to secure these rare gems of true inspiration, which tell of God’s kingdom ever with those who have eyes to see and ears to hear its message, will be eagerly welcomed.”11