Philadelphia, the birthplace of the Declaration of Independence, had been chosen to kick off the festivities earlier that spring. On May 10, with much pomp and ceremony, President Ulysses S. Grant presided over the grand opening of the Centennial Exhibition, America’s first world’s fair. It must have been a stirring spectacle. Over 100,000 visitors poured through the gates on opening day. The grounds, which covered 450 acres, were impressive. Some 200 buildings had been constructed for the event, including a number of massive exhibit halls. Numerous countries participated, but it was America’s culture, industry, and vast natural resources that were in the spotlight. Among the wonders on display were the Statue of Liberty’s arm and torch2 (tours of which would help raise money to build a pedestal) and a Corliss steam engine, which at 650 tons was the largest engine of its kind ever built. Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone made its public debut at the exhibition, as did the Remington typewriter, the world’s first monorail, and Heinz ketchup.3

It was undeniably an impressive affair, one that permanently established America’s place on the world stage. No longer was the United States seen as a country of farmers and backwoodsmen, but rather as home to inventors and artists and engineers. By the time the exhibition closed in November of that year, nearly 10 million people — some 20 percent of the still-young nation’s population — had made the trek to Philadelphia to view it. Among them was Mary Glover, whose glowing report of her visit would be published in one of her Massachusetts hometown newspapers, the Lynn Transcript.4

“As you approach the grounds the view is imposing,” she wrote, calling the exhibition a “mammoth enterprise.” Marveling at the beautiful architecture, monuments, and fountains, she also described a number of other sights that caught her fancy, from “the minerals we lingered to examine,” Russian furs, and jewelry to paintings, tapestries, and sculpture — including a “Butter Bust,” a woman’s face purportedly sculpted from butter (Mrs. Glover was skeptical).

1876 was not just a landmark year for the nation, it was also a landmark year for Mrs. Glover, who had her own independence to celebrate — notably freedom from a lifetime of illness, as the result of a major healing through spiritual means alone a decade earlier.5 She was also living independently for the first time as a new homeowner, having purchased a house at 8 Broad Street in Lynn the previous year.

It was at 8 Broad Street that she finished and published her book, Science and Health, which outlined her discovery of the scientific laws of Christian healing as practiced and taught by Jesus, capping nearly a decade of deep Bible study, healing, and teaching. It was at 8 Broad Street, too, with the nation’s celebrations serving as a backdrop, that on July 4, 1876, she took her first step in launching what would become a world-wide religious movement.

“The first Christian Scientist Association was organized by myself and six of my students in 1876, on the Centennial Day of our nation’s freedom,” she would later note.6

By the following year, the informal group had adopted a constitution and by-laws, and until its dissolution in 1889, the Christian Scientist Association (CSA) would hold regular meetings once or twice a month. Its membership was drawn for the most part from Mrs. Eddy’s7 students, although there were some honorary members and visitors as well.8 As the organizational arm of the fledgling Christian Science movement, the CSA fulfilled an important function. For instance, it was at the group’s meeting on April 12, 1879, that a vote was taken to organize a church.9 Through the CSA, Mrs. Eddy also established The Christian Science Journal, as well as the first reading room and the first Committee on Publication.10

In addition to conducting business, the meetings were also designed to provide an avenue for ongoing instruction in Christian Science and to foster Christian fellowship. Mrs. Eddy “frequently spoke at the meetings,” her student Irving Tomlinson11 would later explain, “which greatly inspired and strengthened the growing band of workers.”12

That summer day in 1876 wasn’t the only Fourth of July with special significance for the Christian Science movement, however. Nearly a decade before the establishment of the CSA, another important step of progress took place on the very same holiday.

In the summer of 1868, Mrs. Glover was living in Amesbury, Massachusetts, a tranquil town on the New Hampshire border. Since her healing a couple of years earlier and the desertion of her husband Daniel Patterson, she had moved from boardinghouse to boardinghouse, and had finally found refuge as the guest of Mary Webster, the wife of a retired sea-captain. Known to Amesbury locals as “Mother” Webster, this kind-hearted woman frequently gathered under her wing those in need of shelter, and she provided Mrs. Glover a room with a view of the river13 and a desk at which to write.14 Mrs. Glover, who boarded there for nearly a year, was hard at work searching the Bible and recording her findings. She was also healing others, including a friend of the Websters.15

It was during her stay in Amesbury, too, that Mrs. Glover took her second student. Not long after her discovery of Christian Science back in 1866, she’d unexpectedly been asked by Hiram Crafts, a shoemaker and fellow boarder at her lodgings in Lynn, if she would consider teaching him the healing method he’d heard her discussing at the dinner table.16 About this call to teach she would later write, “. . . it looked as if centuries of spiritual growth were requisite to enable me to elucidate or to demonstrate what I had discovered: but an unlooked-for, imperative call for help impelled me to begin this stupendous work at once, and teach the first student in Christian Science.”17

Now, while living at Mrs. Webster’s, she met another fellow boarder, a 19-year-old named Richard Kennedy, who would also express interest in learning to heal, and whom she would also soon begin to teach.18

Although Mrs. Glover and her landlady had fundamental disagreements — Mrs. Webster had embraced spiritualism, which Mrs. Glover rejected — relations between the two were largely warm. But Mrs. Webster grew increasingly disenchanted with her boarder’s views on spiritual healing.19 Things came to a head sometime in June, when the landlady’s son came home preparing for his family’s annual summer vacation and evicted Mrs. Glover, along with the rest of his mother’s boarders, one stormy night. Mrs. Glover wound up on Sarah Bagley’s doorstep down the street, where she would board for some weeks that summer, and again briefly in the spring of 1870.

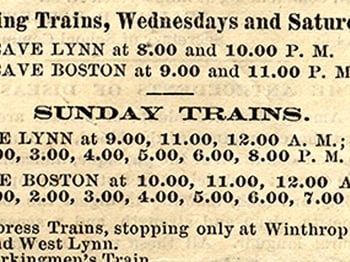

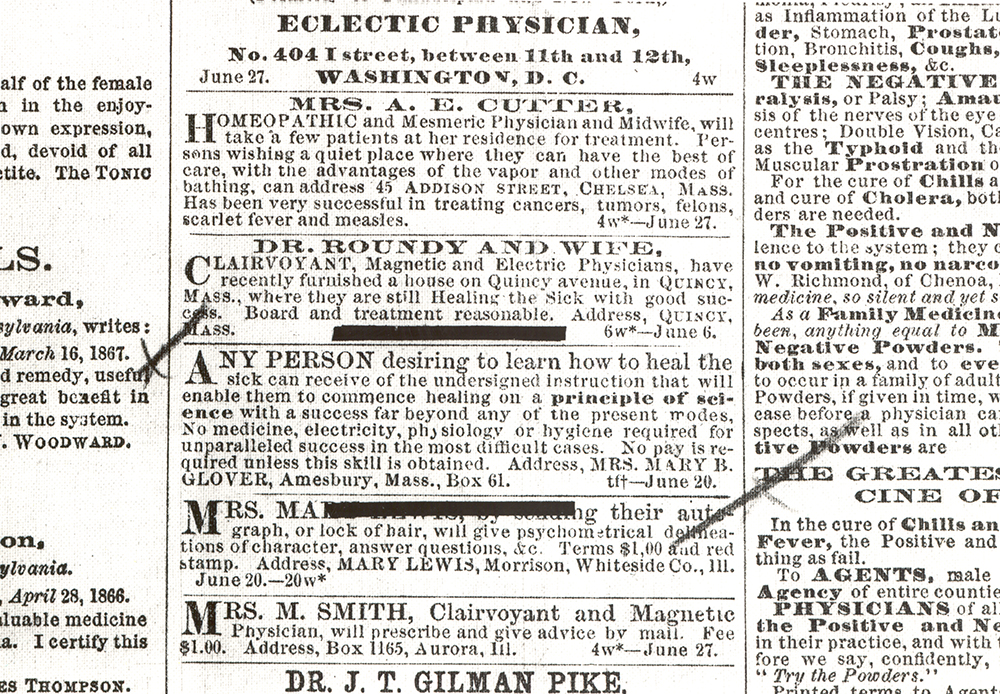

While living with Miss Bagley, Mrs. Glover continued healing and teaching, and on July 4, 1868, she took the significant step of placing an ad in the Banner of Light, a Boston-based weekly newspaper. Tucked in amongst an eclectic jumble of notices for everything from sheet music and photo studios to magnetic healers, homeopaths, tonics, and clairvoyants was this announcement:

Any person desiring to learn how to heal the sick can receive of the undersigned instruction that will enable them to commence healing on a principle of science with a success far beyond any of the present modes. No medicine, electricity, physiology or hygiene required for unparalleled success in the most difficult cases. No pay is required unless this skill is obtained.

Mrs. Glover was officially taking her discovery to a wider audience.

But why advertise in the Banner of Light, a newspaper aimed largely at spiritualists? Perhaps because she had found them to be open-minded, liberal thinkers20 — people like Mary Webster, who had initially embraced her so warmly, and Hiram Crafts, her first pupil, who was a spiritualist before being introduced to her teachings.

Though certainly acquainted with spiritualism — in the late 19th century in America it would have been difficult not to be, given the extent to which the popular movement had permeated the nation’s zeitgeist — that Mrs. Glover herself rejected its beliefs and practices is beyond doubt. That same summer, for instance, her poem “Christ my Refuge” was published in the Amesbury Villager. This early version21 contained the line “I am no medium but Truth’s, to warn / The Pharisee.” And Tomlinson records an incident which also took place in Amesbury, likely that same summer, at a gathering that included poets John Greenleaf Whittier22 and Lucy Larcom,23 among others (notably Luther Colby, editor and publisher of the Banner of Light, which may also account for the placement of Mrs. Glover’s advertisement). While visiting with the group, Mrs. Glover decisively debunked a spiritualist’s attempt to prove that she could contact the spirit world.24

Two Fourths of July. Two big steps onto a wider stage. These twin events, the teaching advertisement in 1868 and the organization of the Christian Scientist Association in 1876, stand as important waymarks in the establishment of the Christian Science movement, whose revolutionary ideas about the true nature of freedom would soon spread around the globe. As Mary Baker Eddy later proclaimed, “Like our nation, Christian Science has its Declaration of Independence. God has endowed man with inalienable rights, among which are self-government, reason, and conscience. Man is properly self-governed only when he is guided rightly and governed by his Maker, divine Truth and Love.”25