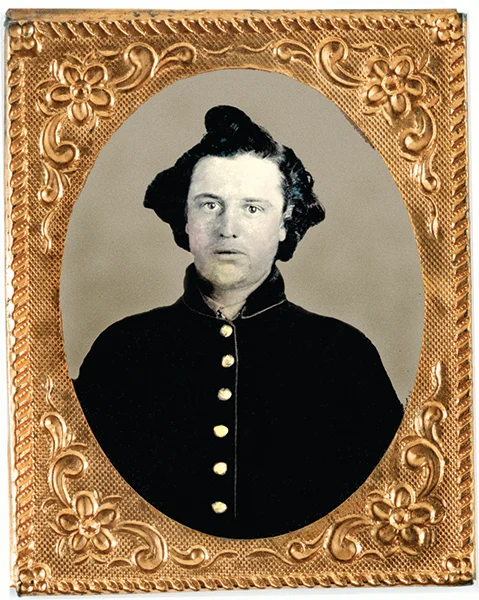

George Washington Glover II ran away to enlist in the Union Army just two days shy of his 17th birthday. After years of farm work in Minnesota, he was eager to join the thousands of men who were leaving their homesteads and enlisting to help preserve the Union. The influx of willing men was so great that almost all of the regiments in Minnesota were full by the time George arrived at the recruiting station. Undeterred, he crossed the Mississippi River and made his way to La Crosse, Wisconsin, where he was assigned to Company I of the Wisconsin 8th Volunteer Infantry Regiment.1

Initially turned away because he was underage, George was given a slot when an officer witnessed him fight several men who had been taunting him outside the recruiting office.

“If you’re old enough to take those two big fellows like that,” the officer said, “you’re old enough to go in the army.”2

George’s Civil War service was a time of toil and hardship, but it also bore an unexpected gift: He was able to reconnect with his mother, Mary Glover Patterson (later Eddy), for the first time in years. Although George was illiterate, he was able to send letters to his mother thanks to a soldier named David Hall, who apparently acted as a scribe for many uneducated men in the company.3 It’s unclear how Hall managed to locate Mrs. Patterson, but somehow he found her address while she was living in Rumney, New Hampshire.4

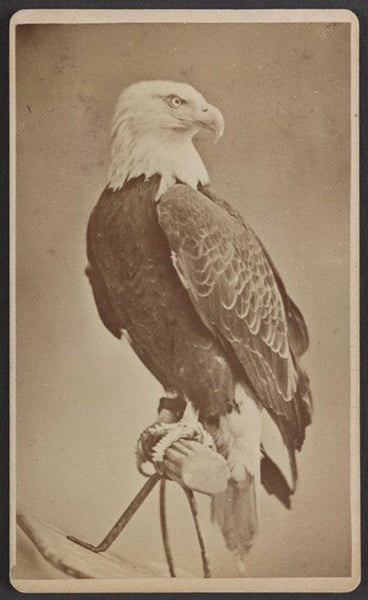

Mary would likely have heard details of the regiment’s constant Southward march, and perhaps even tidbits about “Old Abe.” Affectionately nicknamed after President Abraham Lincoln, Old Abe was a bald eagle, a fellow comrade-in-arms, and the unofficial mascot of the Wisconsin 8th. The Eagle Regiment, as it became known, carried Old Abe through such conflicts as the Battle of Corinth, where a minie ball severed the leather cord that anchored him to his perch and released him over the battlefield. Many Confederate soldiers tried to shoot Old Abe down, but they were unsuccessful. Although the mascot had several close calls, neither he nor any of his eagle-bearers suffered any serious injuries during the war.5

Like Old Abe, George also experienced a close call at the Battle of Corinth, where he was severely wounded and left the ranks for a time. Never one to give up the fight, he re-enlisted after regaining his strength and went on to serve until 1865, when he was discharged on the grounds of a disability. In an interview with Jewel Spangler Smaus nearly a century later, George Glover III (Mary Baker Eddy’s grandson) recalled his father telling him about Old Abe, specifically how the ever-eager eagle bearers, who were closer in age to drummer boys than full-fledged soldiers, often got to witness battles up close because of their important job.6

George and Abe saw countless battles, both managing to see the war to its end. Old Abe would go on to tour the country as a national emblem of Union victory until his passing in 1881.7 George would return West, eventually settling in Lead, South Dakota, where he and his wife raised four children. All the while his mother, by then known as Mary Baker Eddy, was leading the blossoming Christian Science movement in faraway Boston.