Today, the United States observes President’s Day, a celebration of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, both of whose birthdays fall in February. These men, regarded for their wisdom, strength, and humility, are widely considered to be two of America’s greatest presidents. Mary Baker Eddy, a leader in her own right, nearly overlapped with both.

Born 22 years after Washington’s death, she was raised in a time when the nation’s first president was still very much a part of living memory.1 Later, as an adult, Mrs. Eddy lived through the Civil War, witnessing Lincoln’s heroic but tragic presidency. With these two statesmen as a starting point, today’s holiday provides an opportunity to explore additional connections between Mrs. Eddy and other U.S. presidents who were in office during her lifetime.

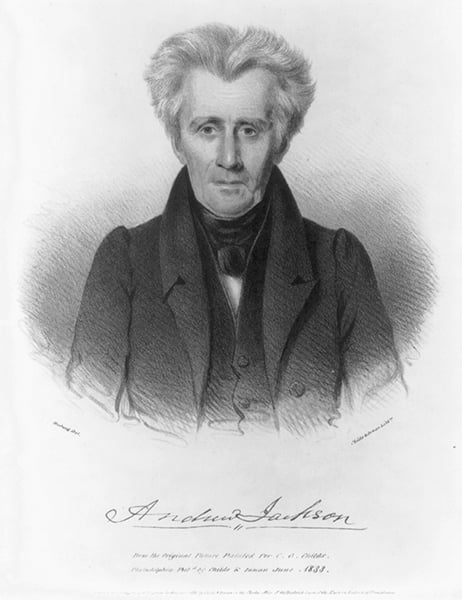

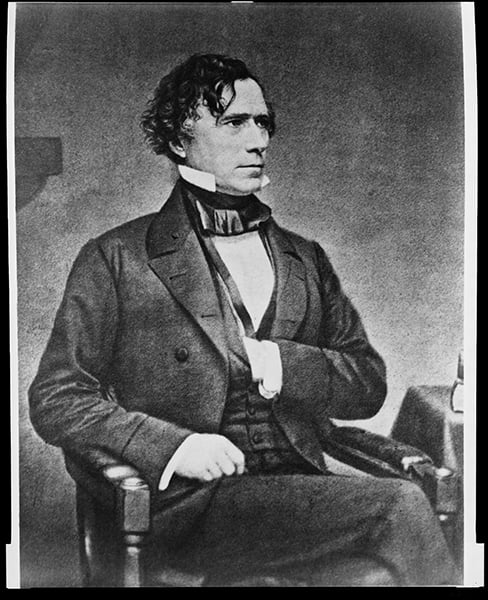

Jackson and Pierce

Despite Mrs. Eddy’s later prominence, she actually met more presidents as a young girl in the rural town of Bow, New Hampshire. In the summer of 1833, weeks before Mrs. Eddy’s twelfth birthday, President Andrew Jackson made a visit to nearby Concord, the state capital. The presidential party, which included future president Martin Van Buren, traveled right by the Baker homestead. If the entire Baker family was not lined up along the road watching them pass, then perhaps they were gathered outside their home on the hill above.2 If they missed Jackson there, then they could have seen him later that weekend at the Old North Church in Concord, where the president attended the Sunday morning service. This was the Baker family’s church, and that morning young Rev. Nathaniel Bouton preached from Luke 10:20, which reads, “… rejoice not, that the spirits are subject unto you; but rather rejoice, because your names are written in heaven.” A witness observed:

The President appeared most affected. Many times did I notice the tear, as it stole down his furrow’d cheek…. The President bow’d his head, and look’d as though his whole soul responded, amen. When I saw him rise, and bend over in the attitude of prayer, his countenance the index of the devotional feelings of his heart, I could not regard this aged patriot without feelings of the deepest heartfelt reverence.3

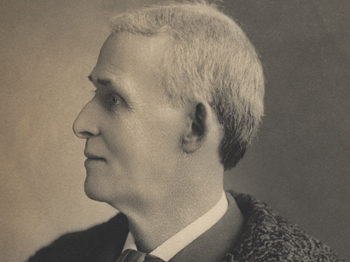

The Bakers may have caught glimpses of Jackson and Van Buren during this trip, but coincidentally there was another man present who was destined for that high office, and with whom the Bakers would become well acquainted. Among the group of prominent local citizens who welcomed Jackson was former New Hampshire governor Benjamin Pierce, along with his 28-year-old son, Franklin, who in 1853 would become the fourteenth president of the United States.4

It’s not clear how the Pierces and Bakers came to know each other, but by 1835 Albert, one of Mrs. Eddy’s five older brothers and sisters, was living with the Pierces in Hillsborough while studying law.5 Eventually, Albert worked directly for Franklin Pierce, supporting the Senator’s law firm and growing political career, while beginning to make a political name for himself, too.6 The two families maintained their friendship throughout the 1830s, exchanging visits and correspondence. During one of these visits, Franklin Pierce is quoted as saying to the teenaged Mrs. Eddy, “Learn all you can, Mary, and some day the State of New Hampshire will be proud of you.”7

Over the course of her lifetime, Mrs. Eddy would indeed achieve a stature worthy of her state’s admiration. However, it would not be until decades later, when she was the publicly recognized leader of a worldwide religious movement, that Mary Baker Eddy would again cross paths in a significant way with any U.S. president.

From Politics to Christian Science

During those intervening years, there is published record of her lively interest in politics: a tribute to Jackson; several patriotic poems about the Mexican-American War; a dinner toast denouncing Whiggery; a sonnet during Pierce’s presidential campaign, among other things.8 Looking back, Mrs. Eddy would later recall newspaper editors asking her to write during political campaigns, and as a result her “goose-quill would wag, however weely, for Pierce and King.”9

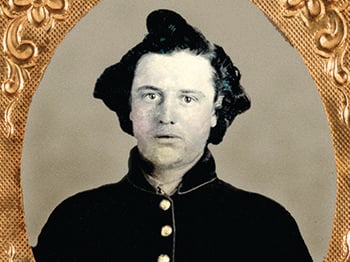

Mrs. Eddy was raised a Jacksonian Democrat, which broadly speaking advocated for the rights of the common man. By the Civil War, Mrs. Eddy, along with others opposed to slavery, had shifted her support to the new Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln, which was pro-abolition.10 She noted, “During my residence in the South my politics were changed — I lost my fun, and gained a higher hope for humanity.”11 Soon, political partisanship would begin to permanently fall away for her.

With Mrs. Eddy’s discovery of Christian Science in 1866, political ideology gave way to an absolute faith in God and His government. This is apparent throughout her writings over the next 40 years, in which concepts of government, justice, and equality — indeed all of democracy’s highest ideals — appear extensively, but nearly always in the context of God’s supremacy. “The Magna Charta of Christian Science,” she writes, “means much, multum in parvo, — all-in-one and one-in-all. It stands for the inalienable, universal rights of men.”12

The 1890s

As the Christian Science movement took root and grew during the 1870s and 1880s, it elevated Mrs. Eddy onto the national stage, where those in prominent positions began to take notice. For instance, after the Daughters of the American Revolution (a patriotic society) was formed in 1890, First Lady Caroline Harrison requested that Mrs. Eddy join their membership.13

During the next administration, First Lady Frances Cleveland may have even had a passing interest in Christian Science, or so Mrs. Eddy heard.14 This notion is not totally implausible given the fact that the Clevelands were acquainted with Sue Harper Mims, a prominent Christian Scientist from Atlanta, and that President Cleveland’s Secretary of the Interior was Mrs. Eddy’s second cousin Hoke Smith.15

Later, in the 1890s under President McKinley’s administration, the U.S. found itself gearing up for the Spanish-American War, and Mrs. Eddy lent her perspective from afar. Weeks after the pivotal sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor, the Boston Herald published an editorial by Mrs. Eddy titled “Other Ways Than By War,” in which she recommended peace but allowed for the possibility of military action.16

The U.S. would follow this latter course, despite McKinley’s reluctance, prompting Mrs. Eddy to close her Communion message that year to The Mother Church with this prayerful counsel: “Pray that the divine presence may still guide and bless our chief magistrate, those associated with his executive trust, and our national judiciary; give to our congress wisdom, and uphold our nation with the right arm of His righteousness.”17

Separately she had sent a letter to First Lady Ida McKinley that acknowledged her support for the president during the nation’s moment of need.18 Several years later in 1901, Mrs. McKinley would receive another letter from Mrs. Eddy, just days after the president was tragically assassinated, in which were words of comfort and a heartfelt tribute to the late statesman, whom she greatly admired.19

The 20th Century

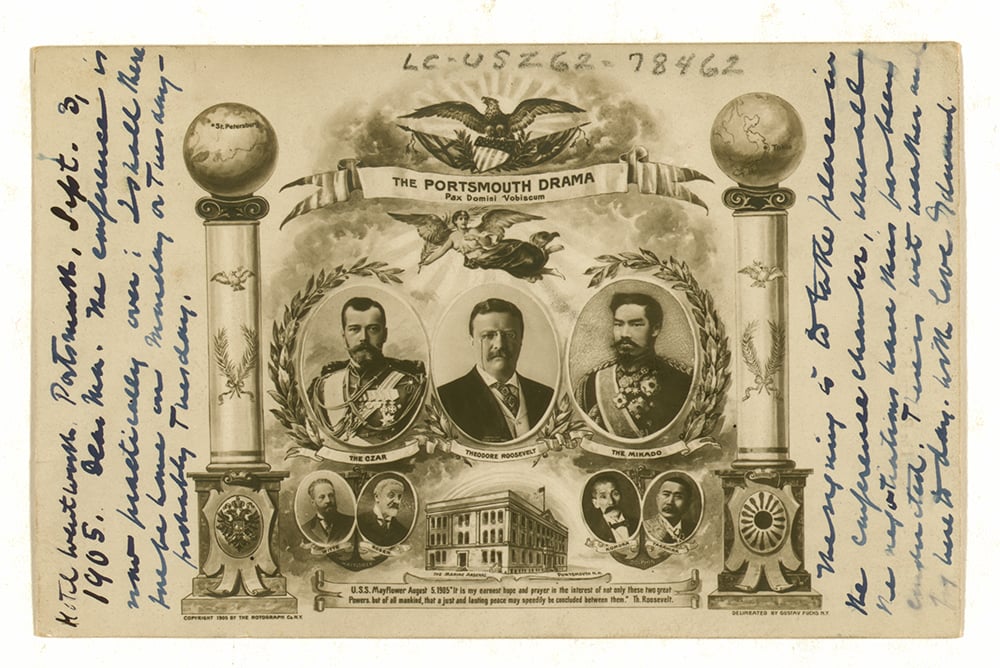

Mrs. Eddy continued to weigh in on national affairs during the tenure of President McKinley’s successor, Theodore Roosevelt. In June 1905, she mobilized Christian Scientists to pray specifically for peace to end the Russo-Japanese War. After several weeks, she requested this special prayer to cease, explaining that “God does not hear our prayers only because of oft-speaking” and that their present need was “faith in God’s disposal of events.”20 Two months later, Roosevelt was brokering a peace treaty in, of all places, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, just 40 miles from Mrs. Eddy’s home. Commenting on these events for the Boston Globe, she reflected wisely, “While I admire the faith and friendship of our chief executive in and for all nations, my hope must still rest in God, and the Scriptural injunction, — ‘Look unto me, and be ye saved, all the ends of the earth.’”21

Roosevelt may not have seen Mrs. Eddy’s statement on that occasion, but in 1908 he was given her brief article titled “War,” published in the Christian Science Sentinel.22 At the time, he was nearing the end of his second term, but was also pushing for support to build up the U.S. Navy. Mrs. Eddy’s short statement addressed the issue: she reiterated her prayer that all peoples put God first, that arbitration was key to resolving international conflict, but she conceded “that at this hour the armament of navies is necessary, for the purpose of preventing war and preserving peace among nations.” Hayne Davis, a Christian Scientist who had recently met Roosevelt, sent him a copy of the article, to which the president replied approvingly, “I wish that all other religious leaders showed as much good sense.”23

Looking Forward

At the turn of the century, Mrs. Eddy looked to the years ahead in a statement titled “Insufficient Freedom,” written for the New York World:

To my sense, the most imminent dangers confronting the coming century are: the robbing of people of life and liberty under the warrant of the Scriptures; the claims of politics and of human power, industrial slavery, and insufficient freedom of honest competition; and ritual, creed, and trusts in place of the Golden Rule….24

The accuracy of her forecast may give readers of today some pause, as the world continues to struggle with many of these same challenges. But Mrs. Eddy also points the way forward — through that prayerful admonition so consistent in her life and writings, and summarized in her later response to the question, “What are your politics?” She answers, “I have none, in reality, other than to help support a righteous government; to love God supremely, and my neighbor as myself.”25 She elaborates upon the promise of this simple yet powerful platform in her primary work, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures:

One infinite God, good, unifies men and nations; constitutes the brotherhood of man; ends wars; fulfils the Scripture, “Love thy neighbor as thyself;” annihilates pagan and Christian idolatry, — whatever is wrong in social, civil, criminal, political, and religious codes; equalizes the sexes; annuls the curse on man, and leaves nothing that can sin, suffer, be punished or destroyed.26