Between 1892 and the end of 1907, Mary Baker Eddy lived at her home, Pleasant View, in Concord, New Hampshire. In January 1908 she moved to a new home in Chestnut Hill, a suburb of Boston. She had purchased this house just a few months earlier. In that short time she had it enlarged to accommodate the large staff needed to support her work as Leader of the Christian Science movement.

Most secretaries in that day were men. Mrs. Eddy worked closely with several male secretaries who handled her voluminous mail, her writings for publication, and her communications with church officers. There was no status-conscious “upstairs/downstairs” division of labor in Mrs. Eddy’s household; the staff at all levels mingled much like members of a family, working together for a common goal: support for Mrs. Eddy.

The three years Mrs. Eddy spent at Chestnut Hill were extremely productive. With the daily support of her household “family,” she founded The Christian Science Monitor; provided for Christian Science nursing; made further revisions to Science and Health and the Church Manual; completed a compilation of her writings, to be published as The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany; authorized a German translation of Science and Health; revised some of her shorter writings; wrote several new articles; and compiled a small anthology of her selected poems.

Household and Kitchen Workers “were not considered ‘servants’”

According to household member Frances Thatcher, the workers who cleaned, cooked, served, stitched, and answered the front door “were not considered ‘servants’”; the role of everyone was to maintain a harmonious, orderly atmosphere in Mary Baker Eddy’s home. Adelaide Still, Mrs. Eddy’s personal maid, recalled, “All of the household were devoted to her and to the Cause. This was true of the household helpers, as well as the ‘watchers’ [those assigned to ‘watch and pray’ in support of Mrs. Eddy and her work].”

Workers in Mrs. Eddy’s homes were carefully screened and selected, first by a committee in Boston, and then by Mrs. Eddy herself. For example, Elizabeth Kelly recalled that after she and her cousins Katharine and Kate Retterer were recommended to the committee, Thomas Hatten was sent from Boston to Ohio to interview them. Some time after his return to Boston, Katharine received a letter requesting that she and Elizabeth come to Boston immediately, where they learned they had been selected to join the household at Pleasant View. The house and kitchen workers dined together and had their own sitting room with a piano, magazines, and other materials for their moments of relaxation.

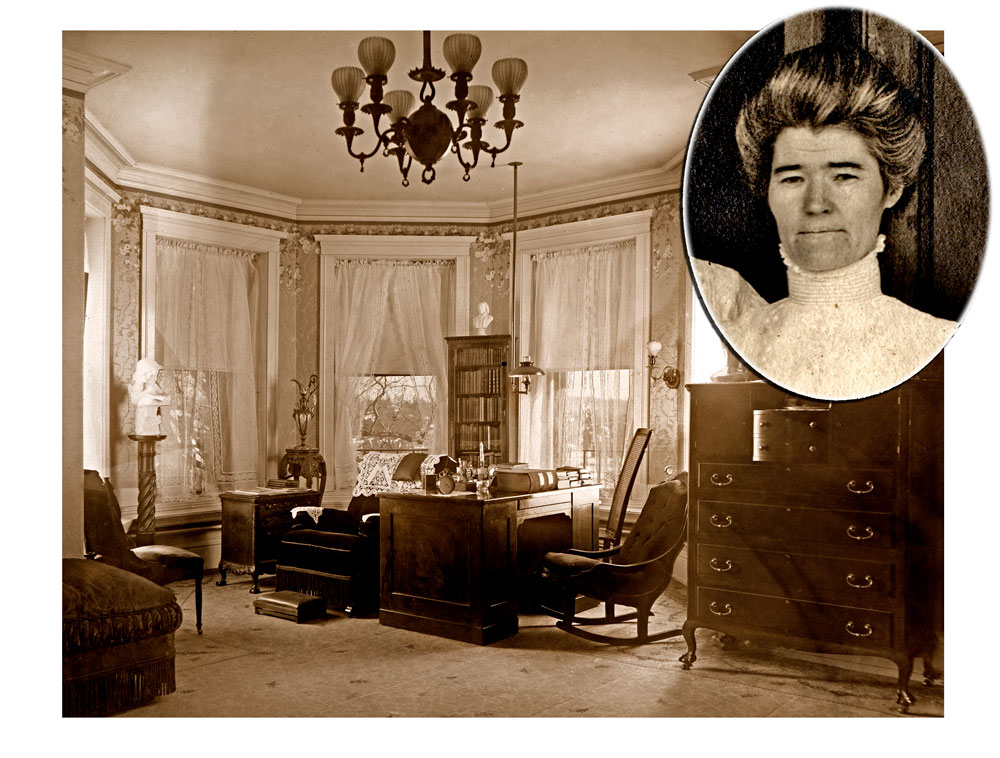

Margaret Macdonald, housekeeper

When Mrs. Eddy first arrived at her new home in Chestnut Hill, she found her rooms uncomfortably large. One month later, her rooms were made smaller, more like the cozy study and bedroom she had left behind at Pleasant View. Over a period of three weeks, she stayed in temporary quarters on the third floor, while her second-floor study was reduced by about six feet, the windows were enlarged, and her bedroom was cut nearly in half. At last it was a place where she could feel at home. After dinner, Mrs. Eddy loved to sit quietly in the bay window of her study, or in the small room above the front entrance, gazing out at the lengthening shadows and the activity beyond her gates on Beacon Street. Once a week, during Mrs. Eddy’s drive, Margaret Macdonald helped sweep and dust her study and other rooms. The housekeepers pressed tacks into the rugs to mark the exact positions of furniture they had moved for cleaning. Margaret had been called to Pleasant View in 1907, later moving with the household to Chestnut Hill. She also helped answer the front door and assisted in planning and preparing Mrs. Eddy’s meals.

Orderliness, neatness, and dispatch

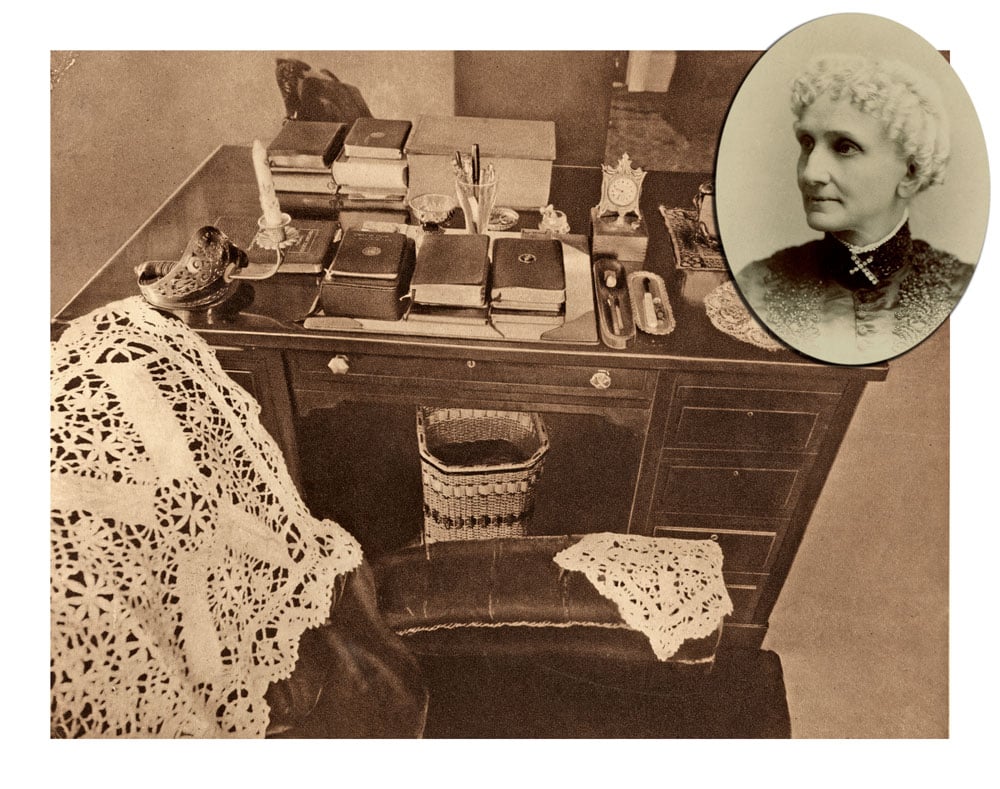

Adam Dickey observed that orderliness, neatness, and dispatch were among Mrs. Eddy’s leading characteristics, and that to her, rooms and decorative objects represented conditions of thought. He recalled, “It was a law with Mrs. Eddy that everything had its rightful place and must always be in that place.” Martha Wilcox and Katharine Retterer were among the housekeepers who accomplished those goals day in, day out.

In November 1910 Mrs. Eddy called Martha to her study. Martha later commented, “I wish you might have heard her expressions of gratitude for her home and her gratitude to those who were caring for her home…and what it meant to her to have such a place in which to do her work and carry on the movement of Christian Science.” Martha also served, at times, in specific prayerful support of the work. At Mrs. Eddy’s suggestion Martha was admitted to the Normal class in December 1910, and went on to serve as a Christian Science practitioner and teacher for the next thirty-six years.

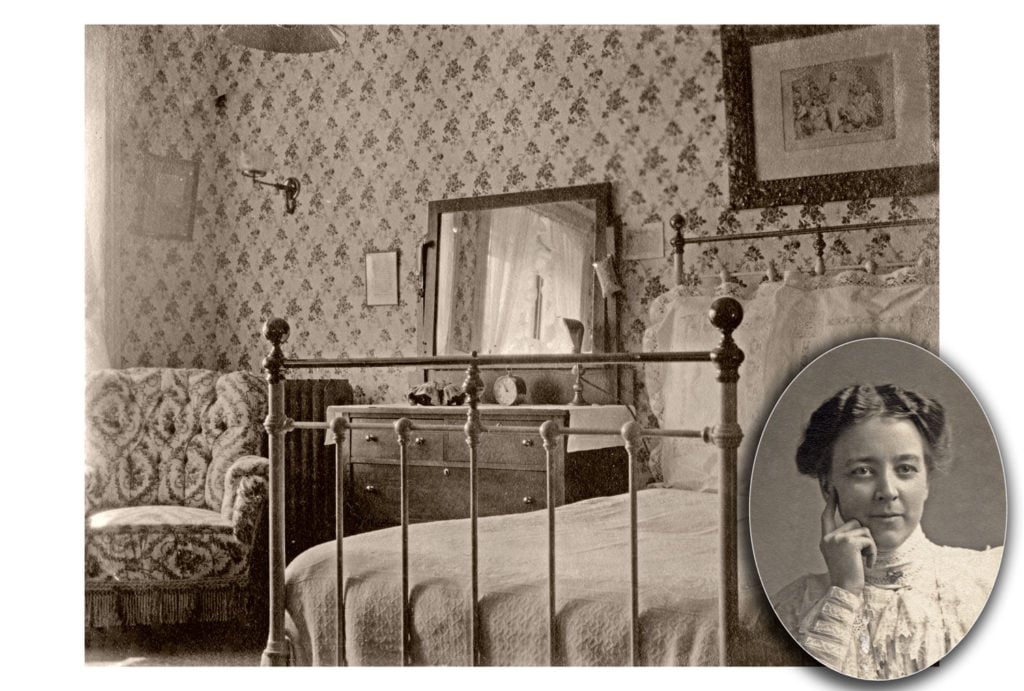

Adelaide Still, Mrs. Eddy’s personal maid

In the 1890s in Bristol, England, a very young Minnie Adelaide Still struggled through years of darkness — through grief, poverty, and unhappiness — to find God. Moving to London, she was introduced to Christian Science in 1900, and later received Christian Science class instruction. Her life improved, and in 1906 she was able to go to the United States. The next year, she was called to serve in the household at Pleasant View. Mrs. Eddy selected Adelaide Still to be her personal maid, saying that she had been praying to God to send her someone — and she believed He had. Because there was already at least one Minnie in the household, Miss Still was called by her middle name, “Adelaide.” After the move back to the Boston area, she gladly stayed on with Mrs. Eddy during the Chestnut Hill years.

In her room, Adelaide rose before dawn each morning, and at six o’clock brought Mrs. Eddy’s breakfast and a pitcher of hot water up from the kitchen. She laid out the clothes for the day, and dusted the study while Mrs. Eddy dressed. Mrs. Eddy did her own hair, except for the last touches, and manicured her nails with a small penknife she kept in her pocket. Adelaide buttoned Mrs. Eddy’s shoes and her high-necked collar and helped her with her jewelry. Then Mrs. Eddy was prepared to begin her day, seated in her large cushioned rocker beside her desk, reading the Scriptures and Science and Health, thinking and praying for a time, often calling selected workers in for instruction — all before taking up her work for the morning.

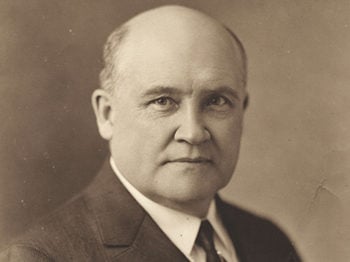

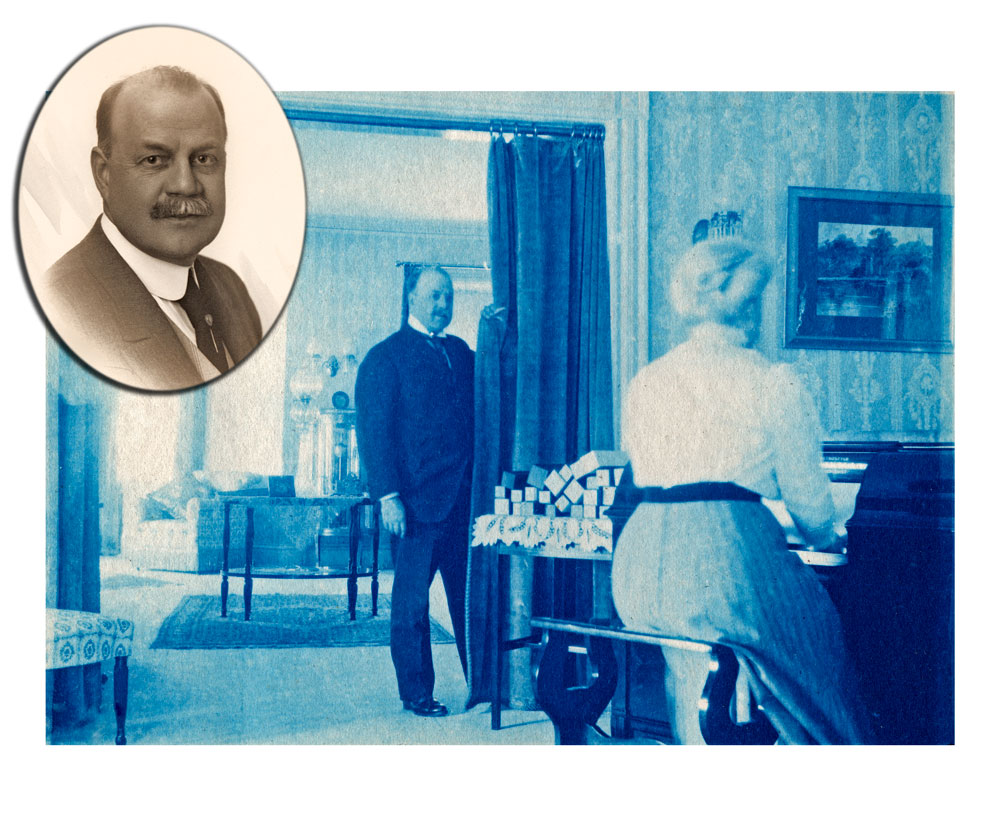

William and Ella Rathvon, prayerful workers

William Rathvon was called to the Chestnut Hill household in November 1908. His wife, Ella, joined him on the staff the following year. William served as a secretary until December 1910. He and his wife were among those regularly assigned to pray in support for Mrs. Eddy and her work. Rathvon had been a businessman in Colorado when he and his wife became students of Christian Science. He later served as a lecturer, Treasurer of The Mother Church, and a member of the church’s Board of Directors from 1918 to 1939. All the workers in the household were expected to be “minute men,” responding promptly to any call from Mrs. Eddy. She called each of them by a simple system of bells, activated by buttons located on her desk, near her chaise, by her bed, and in other convenient places. Each worker had his or her own signal: one ring for Adelaide Still, two rings for Laura Sargent, three for Calvin Frye, and so on. Ten to fifteen rings by Mrs. Eddy — “splurging” she nicknamed it, according to Adelaide Still — called “all hands on deck,” as the workers dropped what they were doing and filed into her study for instructions and teaching. Adam Dickey recounts one such “splurge” when Mrs. Eddy opened the Bible, read the first passage her eye lit upon, and then “gave us all a talk on being ‘doers of the Word, and not hearers only.’”

Frank Bowman, coachman

Mrs. Eddy’s carriage ride gave her a daily respite from her labors. She was often accompanied by Laura Sargent or another member of the household, with Calvin Frye invariably seated beside the coachman. She tried the new motor car once, but preferred her horses. At 1 o’clock the coachman would drive around to the side entrance, where she stepped from her private elevator and entered the carriage. Her drive seldom lasted more than half-an-hour during the Chestnut Hill years, although sometimes she stayed out longer, depending on the demands of the day. One day she was driven to where she could view the great dome of the recently-completed Mother Church Extension in the distance. She said her daily drives were not for pleasure, but “to refute consistent charges that she was dead or incapacitated,” telling her secretary Adam Dickey, “I do not take this drive for recreation, but because I want to establish my dominion over mortal mind’s antagonistic beliefs.” During the first year at Chestnut Hill, the coachman was Adolph Stevenson who, according to one household member, “took such lovely care of the horses and carriage…it was a joy to see him drive up to the house.” Frank Bowman replaced Stevenson in December 1908 and continued through December 1910.

The Sargent sisters lunching on the veranda

Laura Sargent (r) and her sister Victoria (l) had become students of Christian Science due to Laura’s healing in 1883. Victoria had been healed while reading Laura’s copy of Science and Health. Both were actively involved in starting a Christian Science church in Oconto, Wisconsin — the first group to build an edifice for Christian Science services. They are seen here lunching on the back veranda at Chestnut Hill.

In December 1910, Laura had been in Mrs. Eddy’s household continuously since June of 1903 — over seven years. Laura, along with Adelaide Still, stayed on at Chestnut Hill after Mrs. Eddy’s passing in 1910, living there as caretakers. For many months at that time Calvin Frye came daily from Boston to work in his office there. In 1913 Laura Sargent was chosen to teach the Normal Class of the Christian Science Board of Education. Later, after Laura’s passing, Victoria moved into the Chestnut Hill home as its custodian.

Calvin A. Frye, secretary and chief of staff

Calvin Frye, seen here in his office at Chestnut Hill, was the chief of a battery of secretaries who handled the voluminous correspondence addressed to Mary Baker Eddy. The quantity was staggering, even though only mail requiring her direct attention was placed on her desk. Most routine inquiries were answered by secretaries on Mrs. Eddy’s behalf – sometimes with a form letter. Calvin or one of the other secretaries would open and sort her morning mail and bring it to her shortly after she settled at her desk. After her daily drive a batch of letters from the afternoon delivery would be brought to her.

Sometimes crusty and curt, Calvin was not popular with everyone. But Mrs. Eddy esteemed him as totally honest and faithful. She told one of her workers: “Calvin is invaluable to me in my work, because he would not break one of the ten commandments.” He was also valuable as a long-time comrade in arms, toughened by the battles of the earliest days of the movement. A 1902 entry in Calvin’s diary reads: “Mrs. Eddy told me today that I have done more for Christian Science than any other person on earth except herself.”

Adam Dickey prepared for his night “watch”

Adam Dickey’s snapshot was taken as he turned in for the night. The alarm clock on the chair beside his bed was perhaps set to wake him for his turn on the “watch.” Clara Shannon commented that what Christian Scientists might call “working,” Mrs. Eddy called “watching and praying.” Clara wrote, “There was a great need for the Church and our Leader…and as our Leader and those with her were in the front rank of the battle, it meant watching and praying without ceasing.” The metaphysical workers were organized to do this work through the night, assigned to what Mrs. Eddy termed the “watch” — set periods of systematic prayer about specified problems. Mrs. Eddy might dictate brief instructions which would then be typed up for each member of the “watch.” Depending on the need, watchers were scheduled for two-hour periods: 9-11 pm, 11 pm-1 am, 1-3 am, 3-5 am. Adam Dickey was called to Chestnut Hill in February 1908, discovering en route that his term was to be three years, rather than the one year he and his wife had expected. He never wavered, serving those three years as Mrs. Eddy’s confidential secretary. One worker recalled, “Mr. Dickey had a tender, loving attitude towards our Leader, which I shall always remember.” In November 1910 Mrs. Eddy’s last official act before her passing was to appoint him as a Director of The Mother Church, a position he held for over fourteen years.

Laura Sargent, constant companion

Laura Sargent served in Mary Baker Eddy’s household longer than anyone except Calvin Frye. She was a trusted assistant and courier for Mrs. Eddy for many years and a constant companion to her at Chestnut Hill. As with many, it was a need for healing that had brought Laura to Christian Science. In 1883, in Oconto, Wisconsin, poor health had made Laura a near invalid. A family friend had visited a Christian Science practitioner in Milwaukee and had been healed. Traveling to the same practitioner, Laura, too, returned well. Her sister, Victoria, was healed while reading Laura’s copy of Science and Health – as was their mother, who was healed of a broken ankle and promptly urged her daughters to take up the religion they had found. In Chicago in May 1884, Laura enrolled in the only primary class Mrs. Eddy ever taught in the West, and she studied further with Mrs. Eddy in Boston. In 1890 Mrs. Eddy asked if Laura would join her household. She came immediately. Serving Mrs. Eddy, often day and night, occupied much of Laura Sargent’s life for the next twenty-one years — the longest continuous period being from June 1903 to December 1910.

Irving Tomlinson stops to listen to the pianola in the parlor

The easy relationship between all levels of the staff is caught in this snapshot of Irving Tomlinson stopping to listen to Nellie Eveleth playing piano in the parlor. Note the pile of pianola rolls. This was one of three pianos at Chestnut Hill. Another upright was in the upstairs sitting room, the so-called “pink room” where Mrs. Eddy liked to relax with members of her household family, and where Ella Rathvon or one of the others often played and sang for her. Also, William Rathvon recalled pleasant evenings when he and other workers would gather in the sitting room next to the kitchen and sing together around the piano there. Tomlinson, who had been a Universalist minister with a growing disillusionment toward traditional theology, found and studied Christian Science in the 1890s and became a Christian Science practitioner, teacher, and lecturer. Having served Mrs. Eddy in various capacities, including associate secretary in her household, he authored the reminiscence, Twelve Years with Mary Baker Eddy.

Not all toil and care: “Spike” the squirrel

Not all was toil and care in the household. Workers had some leisure time to relax and even take up hobbies like photography and astronomy. Mrs. Eddy encouraged this, purchasing the best telescope available so that members of the staff could go on the roof in the evenings to study the stars. The staff had time to befriend a scraggly but persistent squirrel, who appeared at the kitchen door with almost no fur and its tail almost stripped clean. They nicknamed the animal “Spiketail.” Adopting her as a pet, the staff fed and cared for her so well that her fur filled in. When “Spiketail” no longer fit her full and fluffy tail, she was re-named “Spike.” The tame squirrel would come running when its name was called and would run in and out of men’s pockets looking for the treats they carried for her. In this snapshot “Spike” is diverting Irving Tomlinson from his photography.

Not all was toil and care in the household. Workers had some leisure time to relax and even take up hobbies like photography and astronomy. Mrs. Eddy encouraged this, purchasing the best telescope available so that members of the staff could go on the roof in the evenings to study the stars. The staff had time to befriend a scraggly but persistent squirrel, who appeared at the kitchen door with almost no fur and its tail almost stripped clean. They nicknamed the animal “Spiketail.” Adopting her as a pet, the staff fed and cared for her so well that her fur filled in. When “Spiketail” no longer fit her full and fluffy tail, she was re-named “Spike.” The tame squirrel would come running when its name was called and would run in and out of men’s pockets looking for the treats they carried for her. In this snapshot “Spike” is diverting Irving Tomlinson from his photography.

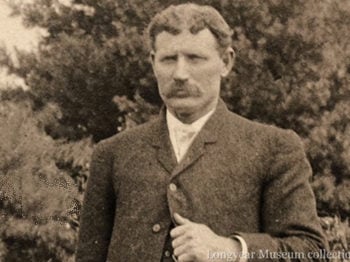

John Salchow, groundskeeper

The Chestnut Hill home, its grounds, carriages, and carriage house stand today as a reminder of all those faithful household workers, whatever their status or position, who gladly served their Leader in whatever way she needed. One of them was groundskeeper and general handyman, John Salchow, the son of a German immigrant farmer in Kansas. He began working at Pleasant View in 1901 and served there and at Chestnut Hill until December 1910. In the mid-1880s Salchow learned of Christian Science and took to reading Science and Health. According to Salchow, after the first few pages he found himself healed of an acute attack of stomach trouble, a condition which had bothered him for years. He soon became a student of Christian Science. Later Salchow was recommended to Mrs. Eddy as a staunch individual who would be a good groundskeeper. He received the letter asking him to come to Pleasant View about ten o’clock on a January morning. By noon he was on his way. In later years he was pointed to as the “man who left his plow in the field and came to serve his Leader.” After her passing, Salchow continued to serve her by working for her Cause in any way he could. He was appointed a utility man at the Christian Science Publishing Society, and performed his humble tasks there, as he said, “with a heart full of love for Mary Baker Eddy and reverent gratitude for all the blessings which Christian Science has brought to me.”