In August 1882, Mary Baker Eddy returned to Boston from a month’s stay in Barton, Vermont, following the passing of her husband, Asa Gilbert Eddy. The loss of one so dear to her was keenly felt. Yet the severe struggles that marked her days and nights in the tranquil rural setting ultimately gave way to a renewed sense of purpose and inspiration.1

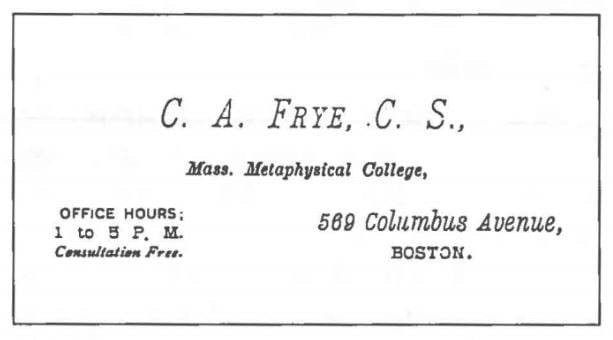

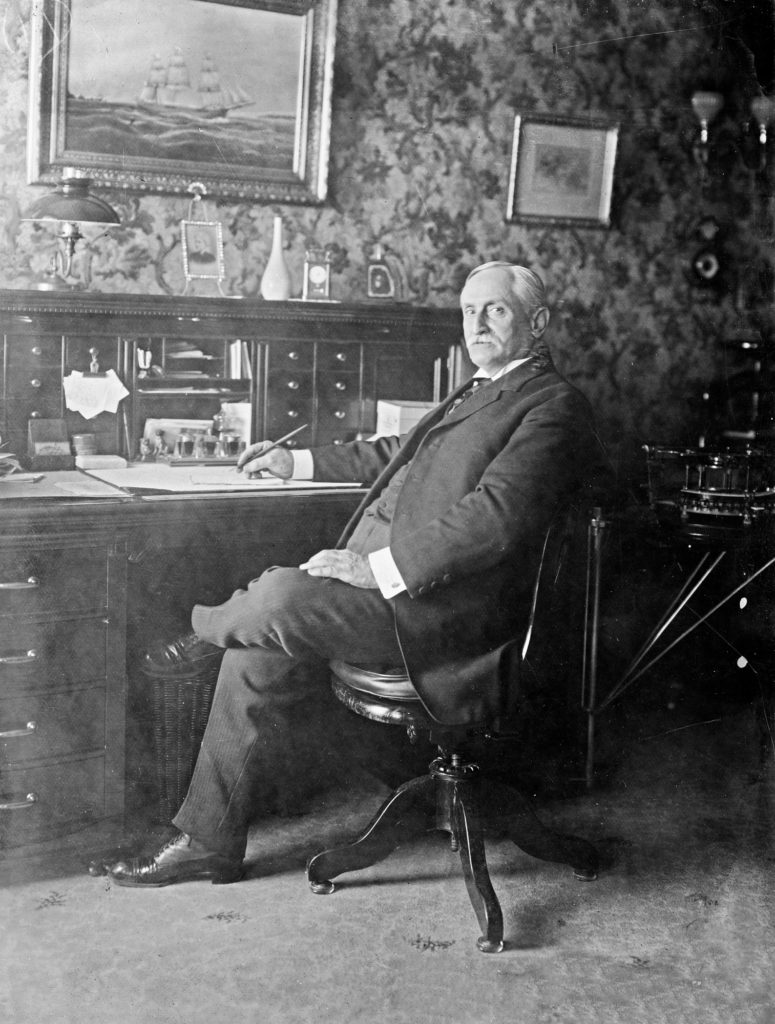

Before leaving Vermont, Mrs. Eddy sent a telegram to Calvin Frye to meet her train in Plymouth, New Hampshire, and accompany her to Boston. His quick response to her call was indicative of his willingness to serve his Leader wholeheartedly and unconditionally. The meeting in Plymouth in the summer of 1882 led to 28 years in Mrs. Eddy’s household, where he served as secretary, copyist, bookkeeper, trustee of her copyrights, coachman, metaphysical worker, and general aide, lending his unfailing support wherever it was needed.

Mr. Frye had been taught by her in Lynn, Massachusetts, in 1881, and after returning to his hometown of Lawrence, he had committed himself to the healing practice of Christian Science. Gilbert Eddy, during his brief acquaintance with the new student, had been impressed with him, recognizing qualities that could be of great help to Mrs. Eddy and the Cause of Christian Science.

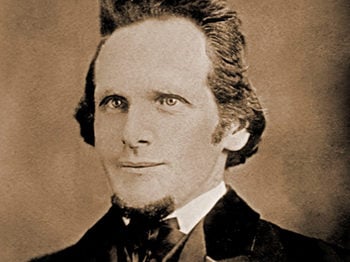

He was born in Frye Village (now part of Andover), Massachusetts, the third of four children of Lydia and Enoch Frye. Calvin’s father had graduated from Harvard in the same class as Ralph Waldo Emerson. A serious illness, which resulted in lameness, prevented the senior Mr. Frye from progressing in his teaching career in Boston. He opened a grocery store in his hometown, and in order to help the family make ends meet, young Calvin and his brother Oscar were called upon to find work. Calvin was apprenticed as a machinist, and after the family moved to Lawrence he was employed at a mill and later at a sewing machine factory.

His life was overshadowed with sadness. In addition to his father’s physical difficulty (which had prevented him from earning enough money to properly educate his sons), Calvin’s mother had been plagued by a mental disorder since the children were young. His sister Lydia was early widowed, and after making her home with their parents again, she bore most of the responsibility for the care of their mother. One year after Calvin’s marriage, his wife Ada passed away, resulting in his return to a home whose atmosphere must have seemed saturated with suffering.

Through these difficult years, Calvin and his family were active in the Congregational Church. The discipline and dedication he brought to his assignments there would stand him in good stead after his reception of Christian Science.

One of Mrs. Eddy’s students had healed a relative of the Fryes in Lawrence, and as a result, the family turned to Christian Science for their mother, who was restored to sanity. Deeply inspired, Calvin and his sister Lydia soon went to Lynn to study with Mrs. Eddy. The year following his instruction, Calvin received the telegram from Vermont that changed the course of his life.

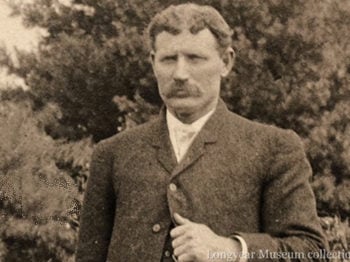

What was it about this man that the Leader of the Christian Science movement found so valuable? What kept him faithful to his promise that he would stay with her, when virtually every other student who came to serve in her household left, either voluntarily or at Mrs. Eddy’s request? A Christian Scientist who knew him points out what he felt it was about Mr. Frye that distinguished him from some who served somewhat shorter terms: “When Mr. Frye responded to Mrs. Eddy’s call he had in him the manhood that recognized the noble womanhood of Principle in her, and this reveals the reason of his great usefulness.”2

For a man living a century ago to put aside personal opinions and ambition and follow the leadership of a woman was unusual, to say the least. And while Mrs. Eddy had many devoted and loyal male students, the demands of being “on call” 24 hours a day, carrying out her directions to the letter, often proved to be more than some men (or women, for that matter) could bear.

Mr. Frye was responsible for the maintenance of Mrs. Eddy’s accounts, and although he had no professional experience in this area, he managed to set up his own system. Mistakes were sometimes made, and yet Mr. Frye’s scrupulous honesty was as apparent in his bookkeeping as it was in everything else he undertook. An auditor who in 1907 examined the books for the previous fourteen years reported: “Mr. Frye has made more errors against himself than against Mrs. Eddy, so that the latter…will have to pay over a balance of cash to Mr. Frye when the time for final adjustment of these accounts arrives. From the examination…it appears that the balance due…to Mr. Frye will amount to $677.41.”3

Calvin Frye’s honesty cannot be over-emphasized, for it surfaces again and again in what Mrs. Eddy and others said and wrote of him. Joseph Mann, who served as caretaker of her Pleasant View estate for seven years, recalled a conversation he had had with Mrs. Eddy about members of her household staff, including Mr. Frye: “With characteristic earnestness, she spoke of his trustworthiness, and concluded by saying: — ‘Calvin is invaluable to me in my work, because he would not break one of the ten commandments.'”4

This faithful steward was not a man who wore his heart on his sleeve. Naturally reserved and disciplined by adversity, he knew the pitfalls awaiting those followers of Mrs. Eddy whose devotion was characterized by emotional excesses. The son of a colleague wrote of Mr. Frye: “To him, there had been one great and lasting emotion: to serve Mrs. Eddy, and that had crystalized into a conviction that was calm, settled and tranquil, — and into a joy of labor that was permanent and unexcitable, and which took the place of vehement emotions, which…were liable to fall through the exhaustion of their own fibres.”5

Though restrained, he was not made of steel, and the well of affection for his Leader — or ”Mother,” as many of the students in her household were apt to call her — went deep. Years later, his nephew recalled seeing Mr. Frye weep openly while relating details of a particularly difficult period in Mrs. Eddy’s life.6

On occasion he touchingly confided his struggles with a sense of inadequacy. To Judge Septimus Hanna, a trusted friend and, at the time, editor of The Christian Science Journal, he wrote a letter of apology after unwittingly advising a course of action at odds with Mrs. Eddy’s instructions: “I shall tell Mrs. Eddy what I did, and let her know it was not a neglect, or delay on your part…. And I hope you will pardon me for the injury it may have been to you. I assure you it will never be repeated.

“O, my brother, you little know the agonies I endure in trying to wisely meet the demands upon me in this position. Gladly would I have given place to some other, and have repeatedly said so, long ago had there been such an one ready to fill the place acceptably to Mother. The way grows harder and harder, until it sometimes seems I can endure it no longer without a respite, a vacation even of a few days, where I could go away and be at rest. But just as I seem ready to drop there comes a renewed sense of courage and the thought ‘how can you leave the Mother unprovided for and desert her?’ and I gather up the little courage I can and try again.”7

Mrs. Eddy was far from unmindful of the demands on Mr. Frye in his key position in her household. Even with the exigencies of her church to attend to, she somehow found time to express motherly concern in a variety of ways, great and small, that added to the comfort of her much-loved student. A temporary inconvenience of Mr. Frye’s once prompted Mrs. Eddy to send her cook the following instructions: “Have soft boiled eggs or poached eggs every day at noon and meat soup at noon and at supper, for Mr. Frye, till he gets some teeth. Remember this.”8

Laura Sargent, herself a faithful worker for many years in Mrs. Eddy’s home, was alert to Mr. Frye’s simple needs as well. In a letter to Mary Armstrong, who at the time was doing a great deal of shopping in Boston for the Pleasant View household, Mrs. Sargent commented on Mr. Frye’s fondness for a certain type of gumdrop that Mrs. Armstrong had brought them: “He said he likes them better than the other candy and it is so very seldom that he ever expresses a wish for any thing I know you will be delighted to get him some.”9

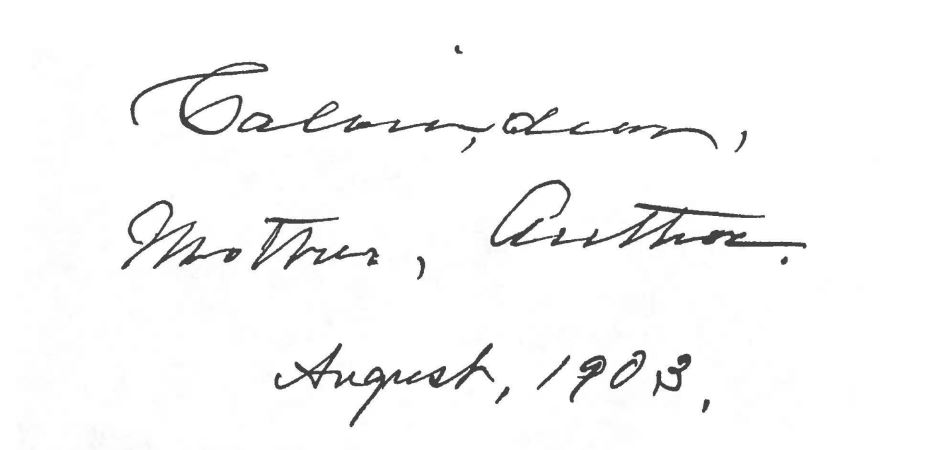

Mrs. Eddy often presented gifts to those students who were particularly helpful to her, and Mr. Frye received many. (He was also generously remembered in her will.) On a noteworthy anniversary, she inscribed a black leather copy of Ecclesiasticus to Mr. Frye, “who has served me twenty years today A.D. Aug. 16, 1902. With grateful memories, M.B.G. Eddy.”10

Mrs. Eddy’s unqualified confidence in Mr. Frye did not keep him from sometimes being misunderstood by some who complained that he was aloof and laconic. Because his position brought him in close contact with Mrs. Eddy, he became an object of resentment, the awareness of which tended to reinforce his wall of reserve. Disregarding popularity, he singlemindedly strove to protect his Leader from the intrusions that would hinder her work for her church. As he himself recognized: “…whatever I do in this direction some one will feel I am in their way, and that were it not for Frye they could have a freer access to Mother.”11 Yet to others he revealed a restrained but genuine warmth, as well as a quiet, dry wit. A description of him in The New York Herald brings out this side of his character: “Delightful of manners, easy, and graceful, Mr. Frye has a bright smiling eye.”12

In 1896 another stalwart early worker, Captain Joseph Eastaman, wrote to fellow students of Mrs. Eddy to solicit their help in purchasing and preserving the house in Lynn where the first edition of Science and Health was completed. One of these letters makes clear how highly regarded was Mr. Frye, especially by those who had known him during the church’s infancy: “The undertaking is approved by Mrs. Eddy. I have twenty names besides my own for $100 each. One of them is Mr. Frye.”13 Apparently Mr. Frye’s participation in an undertaking lent an air of authority to it!

Notwithstanding Mr. Frye’s limited exposure to the world outside of Pleasant View (or later, Chestnut Hill) during his nearly three decades with Mrs. Eddy, it should not be inferred that he was one-dimensional, indifferent to concerns unrelated to the Cause of Christian Science. Even while serving in his demanding position, Mr. Frye managed to keep up with the latest mechanical developments, in which he took a particular interest. In 1910, while living at Mrs. Eddy’s Chestnut Hill home, he and other household members attended an airplane meet at Squantum, Massachusetts, which was, according to a coworker, “the longest vacation Mr. Frye had taken in all his twenty-eight years of service.”14 This “vacation” was about three hours long!

Truly, Mr. Frye served in the front lines, a battle-scarred soldier, but an earnest and utterly committed one. When it appeared that he had succumbed to the enemy’s relentless barrage, his Leader came to his aid. Eyewitnesses have stated that several times Mrs. Eddy restored Mr. Frye when he appeared to have passed away.15 Irving Tomlinson, who was present on one of these occasions in 1908, records that for about a half-hour after Mr. Frye had been found “apparently in a death stupor,” Mrs. Eddy called to him with authority, commanding him “to awaken from his false dream.” Finally he responded, indicating that he would ”come back.” He was soon able to get up and return unaided to his room. The next morning he appeared at breakfast at the usual time, and attended to his daily duties.16

After Mrs. Eddy’s passing in 1910, Mr. Frye continued to work for the Cause, as First Reader of First Church of Christ, Scientist, Concord, New Hampshire, and as President of The Mother Church. He also did some traveling, taking trips to Europe and Florida, and pursued his interest in music. The Frye family was musical (his grandfather had been director of the choir at Old South Church in Andover), and Calvin was no exception, playing the piano and auto-harp quite acceptably. But his most important employment continued to be the quiet witnessing to the life-work of his Leader.

In an article published in the Christian Science Sentinel entitled “Tilling the Ground,” Mr. Frye wrote of the angel, or “message from divine Love,” that appeared to the shepherds in the fields near Bethlehem, announcing the birth of Jesus. He observed: “This message was received by the shepherds who were awake through the night hours, but we are not told that any less watchful people than they either heard or saw this remarkable manifestation of divine Love in their midst.”17 How poignant that the man who penned this statement knew as well as any of Mrs. Eddy’s students what it meant to be “awake through the night hours”! Indeed, Mr. Frye often watched and prayed long into the night when the way seemed dark. Perhaps these solitary vigils, which often resulted in the joyful reception of similar angel-messages of peace, were part of the reason Mrs. Eddy credited him with having done more for her and for Christian Science than any other student.18

Back in 1881, when the Church of Christ, Scientist, was in its formative period in Lynn, a group of members turned against Mrs. Eddy and withdrew from the church. After the meeting in which the action was announced, Mr. Frye, a new student at the time, stayed behind to lend support to his teacher. That night, he and two other students were witnesses to what evidently was a sacred experience to them: Mrs. Eddy’s vision of a new beginning for her church and its loyal adherents, and of her own mission, inextricably linked with the church she had founded.19

That vision never left Mr. Frye. As the church extended its boundaries, moved to Boston, and reached out to embrace a world with its message of healing and regeneration, he realized more and more the import of what he had been taught, and the deep spirituality and unswerving devotion to God of the woman who had imparted these teachings. Something of this is reflected in a resolution passed at a meeting of the Board of the Massachusetts Metaphysical College Corporation in 1889 and recorded by Mr. Frye as clerk: “…everlasting gratitude is due to the President, for her great and noble work, which we believe will prove a healing for the nations, and bring all men to a knowledge of the true God, uniting them in one common brotherhood.”20

The church was to undergo great changes, growing far beyond its humble origins in Lynn. Calvin Frye was one of the few who grew with it, and yet his unpretentious character remained fixed. About a year before his passing in 1917, Mr. Frye, during a visit to Mary Beecher Longyear’s home, inscribed in her guest book the following cryptic message: “A name is a shadow which we sometimes find much greater than the man that is behind.”21 Because of Mr. Frye’s self-effacing tendency, it would not have been out of character for him to have had himself in mind in making this observation. In the light of his accomplishments, however, it might be well to consider the Scripture defining true greatness: “…whosoever will be great among you, shall be your minister: And whosoever of you will be the chiefest, shall be servant of all.”22