On January 26, 1908, Mary Baker Eddy and her household moved from Concord, New Hampshire, to her new residence in Chestnut Hill on the western outskirts of Boston. As she set out to make the house into a comfortable home for her staff and herself, she directed where to place each of her framed works of art,1 many of which were gifts from grateful students of Christian Science. Mrs. Eddy valued each work for its subject and the spirit the picture expressed. The art in her house reflected her own thoughts and feelings and documented significant events in her history. According to her secretary Adam Dickey, Mrs. Eddy thought that “every picture, every ornament, and piece of furniture in her rooms represented a thought,” and “she wanted that thought to harmonize with the mental atmosphere of her room.”2

During 2013, Longyear took the first steps to restore the look and feel of the house Mrs. Eddy would have known. Museum staff worked with The Mary Baker Eddy Library and The Digital Ark, a digital archiving and media development company in Providence, Rhode Island, to make full-size, archival giclée reproductions of selected artwork and framed documents that hung on the walls at Chestnut Hill. The originals remain in the Library’s collection. Frames were chosen to closely approximate the actual frames. To date, nine of these reproductions have been installed in the house, where they add meaning to visitors’ tours.

This article presents several of the works that once again, in replica, grace the walls of the home of the Discoverer, Founder, and Leader of Christian Science.

Gift From a Comrade-in-Arms

Head of Christ by Boston artist Mary A. Batchelder is given a notable place in the front parlor on the first floor.3 This likeness of Christ Jesus was a memento of the early days in Boston when Mrs. Eddy battled and overcame harsh opposition. The painting was a gift from Julia Bartlett, a comrade-in-arms in those days. Miss Bartlett had a remarkable history as a Christian Science practitioner, and she was the first of Mrs. Eddy’s 1884 Normal class students to teach her own class in Christian Science.4

Miss Bartlett owned a treasured picture of Jesus, believed at the time to be copied from an authentic portrait carved in the first century A.D.5 Based on that image, she had this painting made as a gift for her Leader. It had just been framed when, in 1885, Rev. Joseph Cook voiced a bitter attack on Christian Science at Boston’s massive Tremont Temple. Mrs. Eddy protested, and at his weekly lecture the coming Monday he reluctantly allowed her to respond. At the appointed time, Miss Bartlett rode with her in the carriage across town to the church. Mrs. Eddy was greeted coldly by Rev. Cook, endured insulting remarks, and was allotted just ten minutes to address a mostly hostile audience. It was an ordeal.

Afterward, Miss Bartlett recalled, “We rode quietly home…. When we reached home, she went to her room, where she remained alone…. No one but herself could know the burdens of that hour.” Miss Bartlett felt this was the moment when the painting might help raise her teacher’s spirits, and she offered her gift . She recalled, “[Mrs. Eddy] was deeply moved and expressed her love and gratitude and joy. I could not say all that this picture brought to her thought of the real Christ Jesus as one who had suffered and triumphed over all claims of evil.”6

‘Before the Jaws of Beasts’

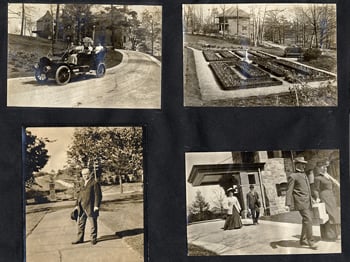

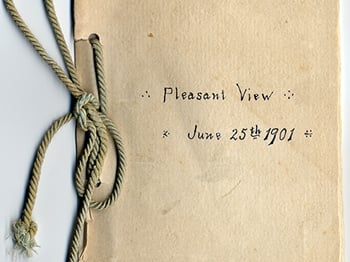

At Pleasant View, Mrs. Eddy had a depiction of the prophet Daniel that spoke to her of her own experience. On the wall of her library was an engraving of the well-known painting by Briton Rivière titled Daniel’s Answer to the King. In it, Daniel faces away from the lions to announce to the king, “My God hath sent his angel, and hath shut the lions’ mouths, that they have not hurt me.”7 Indeed, the lions’ mouths are closed as they circle, cowed and constrained, behind him.

This picture’s meaning for Mrs. Eddy had roots in her childhood. She told a secretary that when she was eight years old, her mother read her the Bible story of Daniel praying to God three times a day. She made up her mind that she, too, would speak to God daily — not just three times, but seven times. Moreover, she recalled, she chalked up each prayer on a wall of the woodshed where she prayed, so she would not lose count and forget one.8

As she grew to lead the Christian Science movement, Daniel’s example deepened for her. In 1895, she received the fine engraving of Daniel’s Answer to the King as a gift from her student Julia Field-King in London. Mrs. Eddy responded, “A million times I thank you for that wonderful picture,” and commented, “So many years to be before the jaws of beasts as I have been is more than Daniel’s experience.”9

On New Year’s Day 1896, she said to her dinner guests, “Come into the library. I have a new painting, and I want to talk about it to you.” With the little group seated facing the picture, she drew a lesson from it. “You see,” she told them, “he has turned his back on the lower or bestial elements of mortal mind and is giving his answer to the King — to the highest. Th at is what I have always done.”10

Over the years, she learned to turn her thoughts from evil and look upward, like the upturned face of Daniel in the picture on her wall. She told something of that to former Methodist minister Rev. Severin E. Simonsen. He recalled:

When error seemed to press her exceptionally hard, she would leave her work for a few minutes and come and stand before this picture, and study anew the calm and loving manner in which Daniel looked steadfastly to God and God only. He paid no heed to the lions or seeming danger, letting his dear heavenly Father care for the ferocious beasts and keep them at a safe distance. With new and fresh courage, she said, she would return to her work, with a heart full of joy and gratitude for His protecting care.11

In that spirit, she met the challenges of 1907 — her last year at Pleasant View — when clergymen, writers, and the medical establishment joined in attacking Christian Science and its Leader. Elements in the press were spreading the lie that Mrs. Eddy was sick, dying, or dead. And family members were trying to take control of her assets in a trumped-up lawsuit, known as the Next Friends Suit.12 After months of strenuous metaphysical work by Mrs. Eddy and her household, the lawsuit collapsed. By autumn, Mrs. Eddy was able to resume planning her move back to Boston, but her metaphysical workers continued to address the ill will still rumbling in the air.

During some of these difficult days, Irving C. Tomlinson was at Pleasant View as a secretary and metaphysical worker.13 Another image of Daniel by Rivière hung in Tomlinson’s room. It depicted Daniel contemplating the snarling lions, their teeth bared for the kill. One night while Tomlinson was studying Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mrs. Eddy, there was a loud crash beside him. The next day, he reported to Mrs. Eddy that the framed engraving of Daniel in the Lions’ Den on his wall had fallen to the floor. His note to her suggested, “May not this signify, as you have been so clearly teaching us, that the day of contemplating error, in the attempt to heal it, has come to an end?” Mrs. Eddy was pleased with Tomlinson’s interpretation. She called the household together and had him repeat it to them. The picture focusing on the roaring lions was stored away in the attic, and we have no record of whether it made the trip to Chestnut Hill.14

Tomlinson observed, “The picture of Daniel in the library, with his back on the lions and his face toward the Light, remains secure.” That picture definitely did go with Mrs. Eddy to Chestnut Hill, where she placed it not downstairs in the library, but in her bedroom at the foot of her bed. Daniel’s Answer to the King was likely one of the first things that met her eyes each morning and one of the last things they rested on when she retired at night. It is a graphic reminder to visitors to Chestnut Hill today of Mrs. Eddy’s words in Science and Health: “Understanding the control which Love held over all, Daniel felt safe in the lions’ den, and Paul proved the viper to be harmless.”15

An Artistic Collaboration

In the Chestnut Hill library is an early version of Truth versus Error, which illustrates one verse of Mrs. Eddy’s poem Christ and Christmas:

To-day, as oft, away from sin

Christ summons thee!

Truth pleads to-night: Just take Me in!

No mass for Me!16

In the poem’s glossary, this verse is linked to the third chapter of Revelation:

I know thy works, that thou art neither cold nor hot…. Because thou sayest, I am rich, and increased with goods, and have need of nothing;…be zealous therefore, and repent. Behold, I stand at the door, and knock: if any man hear my voice, and open the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with me.17

Throughout 1893, Mrs. Eddy worked closely with painter James Gilman to illustrate the poem. Her concept for this illustration, according to Gilman, represented the messenger “bearing the message of Christian Science Truth,” as a young woman “knocking at the door of … a typical abode of the personal mortal sense of life and things.”18

Mrs. Eddy seemed to associate that concept with her own experience. Preparing for a meeting with Gilman, she had gathered photographs of herself in earlier years for him to refer to in visualizing the woman. When he unveiled his drawing, however, she felt he had depicted the concept perfectly. the photos were put aside and not used.19

As they revised the illustration, Mrs. Eddy’s quick sense of humor came into play. She had requested a book to be in the woman’s hand. But when she saw the drawing, she said it suggested “a book agent” making a door-to-door sales call! She and Gilman erupted in laughter at the thought. the book would later be replaced by a scroll, as depicted in the version in her home. She later directed Gilman to remove the label “Truth” from the scroll and “mortal mind” from the door, since, she told him, viewers no longer needed “labels to prevent their libels.”20

The framed drawing at Chestnut Hill is the result of the two artists’ collaboration. the illustration visually evokes Mrs. Eddy’s words in the Preface to Science and Health: “Truth, independent of doctrines and time-honored systems, knocks at the portal of humanity.”21

Angel With the ‘Little Book Open’

In 1899, Katharine Fitchner Swope, a highly regarded New York artist, undertook a major painting based on the following passage in Science and Health:

St. John writes, in the tenth chapter of his book of Revelation: —

And I saw another mighty angel come down from heaven, clothed with a cloud: and a rainbow was upon his head, and his face was as it were the sun, and his feet as pillars of fire: and he had in his hand a little book open: and he set his right foot upon the sea, and his left foot on the earth.

This angel or message which comes from God, clothed with a cloud, prefigures divine Science.22

Mrs. Swope had become a member of the Mother Church in 1898, after taking Primary class instruction from Laura Lathrop in New York. From the artist’s letters, it seems that she may have been given some direction and encouragement from Mrs. Eddy in the design of this painting.23

The finished work, titled Revelation, stands an imposing six and a half feet tall. In 1901, Mrs. Swope had it mounted in a custom-made dark frame, then sent it to Pleasant View as an Easter gift for Mrs. Eddy. Her instructions placed it high on the wall; she wrote, “The horizon of the picture should be on a line with the eye — which greatly ennobles the figure.”24 the picture’s location in the Pleasant View parlor did not quite realize her intention, but at Chestnut Hill it was placed at the top of the stairs, thus fulfilling the artist’s vision.

By Dawn’s Early Light

In October 1906, aft er completion of the Mother Church Extension, Mary Baker Eddy asked the Christian Science Board of Directors to commission a painting of the church for her home. They engaged John J. Enneking, a distinguished Boston Impressionist.

In 1907, he submitted two alternate sketches. One showed the church at night with its windows illuminated in the moonlight. the other showed the great dome rising into the morning light aft er a storm had passed over it. Descriptions were sent to Mrs. Eddy, and she chose the latter of the two concepts.25

During the storms that buffeted her church in 1907, such as tumult in the press and the Next Friends Suit, the artist wrote Mrs. Eddy describing his work in progress:

I have named the picture “The Dawn”…. I represent the Christian Science Church rising unharmed out of the smoke of contending factions, the struggle of creeds and all sorts of “isms” for supremacy. the upper part of the picture is represented in a glow of light,…the whole mass of light prophesying fair future conditions.26

Mrs. Eddy was pleased with these ideas, and had the letter published in the Christian Science Sentinel. She was even more pleased when she saw his painting for the first time, hanging in her library at Chestnut Hill. She wrote him, “Your picture of the Mother Church of Christ, Scientist, distinguishes the artist, points a history, and illumines it.”27

Mrs. Eddy would view the great stone edifice in Boston only once, from the window of her carriage. But in the artist’s symbolic concept her church could be seen, having endured a night of storms, standing firm in dawn’s early light.