To many who have been visitors to the Longyear Museum in Brookline, Massachusetts, one of the outstanding features of their visit has been a walk through its colorful gardens. These gardens have been a continuing source of pleasure, first to its original owners, John and Mary Beecher Longyear, and since the Museum was opened in 1937, to its thousands of visitors.

As readers of the Quarterly News may know, the Longyears moved to Fisher Hill in Brookline, in 1906. The landscaping around their mansion was planned after the manner of the gardens found in the Hudson River Valley at that period.

Many sets of landscape drawings exist in the Longyear collection, the first made in 1904 by B. M. Watson of Boston while the building was still under construction. Photographs taken in 1909 show that extensive flower gardens were in bloom by then. In 1911, Buckenham and Miller, self-styled “landscape engineers,” made elaborate drawings, showing in considerable detail trees, shrubs, and flower gardens. Thirty-seven beds were carefully laid out and specific flowers designated in their drawings. Records are lacking as to whether some, or all of these beds were installed.1

Later, landscape architect, Elizabeth Leonard Strang, and decorator, Alice E. Neale, contributed to the Longyear gardens. Elizabeth Strang’s drawings in 1925 and 1926 of the rose garden and “sunken” or formal garden were also in unusual detail and are the basis of these two gardens as they exist today.2

Over the last eight decades, it is understandable that there have been many changes in design and arrangement, in garden practices, and in choice of varieties. Furthermore, the gardens must change by season, so the whole matter of display has been, and is, dynamic not static.

Our readers living close to the Boston area do have a more frequent opportunity to enjoy the flowers of Longyear than those hundreds of miles away or even on another continent. It is our intent here to bring those distant readers to Fisher Hill and describe for them, through word pictures, what these lovely gardens are like.

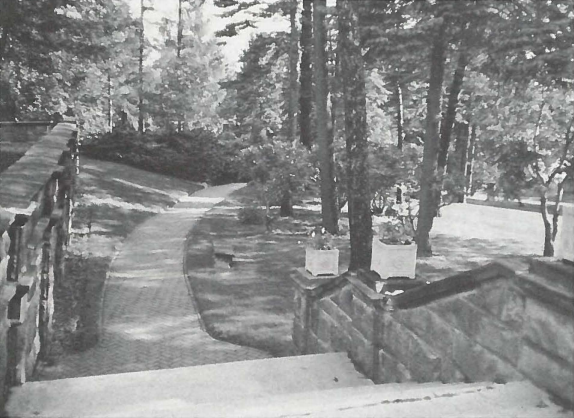

Picture the wrought iron entrance gate on Seaver Street, and the winding road up the hill to the paved parking area in front of the brownstone mansion. On the right beyond the gates, in the early spring, there are blazing tulips and other bulbs; later peonies, rubrum and wax begonias. In the background are forsythia, and magnolia with its showy pinkish-white blossoms. On the left are viburnum, weigela and mock orange-all flowering shrubs.

In front of the Museum and to either side of the entrance stairs are both tuberous and wax begonias. Heavenly blue morning glory climbs the side of the nearby gazebo (one of two gazebos at Longyear brought from Pleasant View, Mrs. Eddy’s home in Concord, New Hampshire).

Four large and six smaller pots variously placed on the front porch balustrade and on the low walls around the parking area, contain red geraniums, white petunias and vinca vine. Below the steps leading to the front lawn, caladium with its heart-shaped variegated leaves, pansies, and rudbeckia or daisy-like cornflowers have sometimes been planted.

As we walk south along a brick path, the way opens up to a “cloistered” garden, with stepping-stones leading down through the pine trees to another gate on Leicester Street. In this garden the visitor is surrounded by a multitude of shapes and colors. It is possible only to list the varieties greeting the eye:

- lily of the valley

- primrose

- obedient plant

- monkshood

- gentian

Tracing the pathway uphill toward the swimming pool, we come to the “wishing well,” which over the years has been covered with climbing roses and surrounded by border gardens. One garden has bright spring bulbs and forsythia, whose blooms are replaced in time by columbine and white-flowering deutzia, and still later by anemone or windflower.

In other gardens near the wishing well, on one side is nicotiana, on the other, daylilies and peonies. In front of the rose garden, colorful impatiens are massed.

Ah, the rose garden! There is something about a rose garden that attracts everyone. The opportunity to stroll through a beautiful garden and enjoy the individual roses is much to be desired. The Longyear rose garden was originally laid out with a sundial in the center. This sundial still challenges visitors with the words:

MY FACE MARKS THE SUNNY HOURS

WHAT CAN YOU SAY OF YOURS

At one end of the garden with pine trees behind, provision has been made for rest and enjoyment of the garden in the form of a semi-circular brick and stone patio with seating.

Some of the existing rose bushes were planted years ago, but many now have been replaced. A dozen hybrid tea roses were added to the garden as late as two years ago in the spring. It is expected more bushes will be added this year. Some favorites are Tropicana, coral color and fragrant; and Queen Elizabeth, bright red and hardy.

Returning to the brick walk, with the terrace wall ahead of us, we note the pink and lavender climbing roses on the wall. At the very bottom of the wall, in early spring-usually February-snowdrops pop out, sometimes through the snow. Much later in the season we would find in this garden delphinium, sweet peas and asters. In front of them and all the way out to the walk, phlox, sweet William, Shasta daisies, candytuft, pinks, and chrysanthemums would bloom, each flowering depending, of course, on the time of year. The green edging is hosta and pachysandra which is often used around the Longyear gardens.

Further along the walk toward the pool are still more climbing roses on the wall, and a few varieties not in the adjoining bed. These are: dahlias, red verbena, and alyssum.

At the 47 by 106-foot swimming pool, the corner beds, which flank the stairs leading into the pool, contain blue salvia and white double petunias; in four large urn-shaped pots, beside the stairs, are red geraniums, petunias, and vinca vine.

In the area behind the swimming pool are a number of different varieties growing four to eight feet high. Rows of lupine and peony are in front of spider flowers (cleo me), coreopsis, and hollyhock. To the rear of them are tall spiked spirea (astilbe). Border gardens here also include yellow alyssum, foxglove, and Canterbury bells.

Around the rear of the Museum building are the cutting gardens and the formal garden. The flower beds for cutting are at the very rear of the property, but the location does not mean they are any the less colorful. The three main beds are divided in thirds by two rows of cannas. The flowers in-between cover a gamut of varieties. The common ones are:

- snapdragon

- marigold

- zinnia

- gladiolus

- delphinium

The less common ones are:

- pincushion flower (scabiosa)

- globeflower (trollius)

- globe thistle

- Stoke’s aster (stokesia)

- penstemon

- obedient plant (physostegia)

- acidanthera (related to the gladiolus)

- baby’s breath (gypsophylia)

Bordering plants to these beds are:

- peonies

- ornamentalligularia

- iris

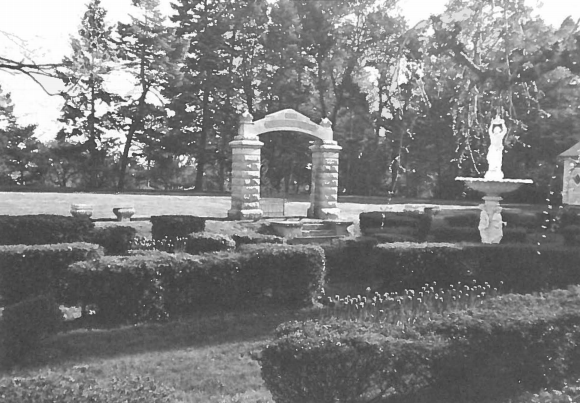

The formal or sunken garden has in its center a fountain, and on one side, an arch, both originally at Mrs. Eddy’s home at Pleasant View. At the end of the garden facing the Museum is a statue of Mary Baker Eddy by the famous sculptor, Cyrus Dallin.3 The azalea hedge, which dominates the garden, is an unusual variety with surprisingly beautiful, tiny magenta blossoms coming forth in early June.4 Corner beds contain snapdragons; and the four center beds have tulips, which later give way to wax begonia and snapdragons. Wax begonia line the walkway from the building to the fountain. Under the mulberry trees on the opposite side of the garden from the arch is a profusion of mixed impatiens. The pots around the formal garden contain the familiar combination of red geraniums, white petunias, and vinca vine.

With all these flowers outside in the gardens, it is to be expected that beautiful bouquets find their way into the Museum, and that is indeed the case. Fragrant and colorful bouquets are placed in the entrance rotunda to greet visitors. The wide range of varieties available for bouquets inspire those who do the flower arranging to use their imagination and expertise. Other bouquets placed in the Longyear library, and often elsewhere in the building for concerts and other functions, brighten corners and gladden the eye. The Longyears loved flowers and plants in their home, and the Museum is carrying on this tradition.

Looking back over the cryptic, and unfortunately, rather incomplete notes of the Longyear gardener in the 1920’s, we find that the most common spring bulbs planted were narcissus, hyacinth, and tulip. In 1927 and 1928 favorite plants were also lantana, lobelia, petunia, nicotiana, aster, zinnia, marigold, California poppy, portulaca, larkspur and snapdragon. Records in 1929 list, in addition, gloxinia, coleus, celosis, verbena, salvia, scabiosa, stock, calendula, cosmos, balsam, and rhodanthe (related to everlasting). Vegetables and herbs were not to be forgotten. Among others, parsley, lettuce, tomatoes, peppers, cabbage, cauliflower, and celery were planted to be used in the Longyear kitchen.

In passing it might be mentioned that in 1925 the gardener noted briefly the following:

- September 26-first killing frost

- October 10-snow

Winter came early that year!

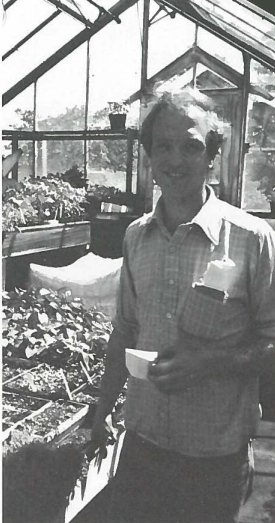

That the gardens are outstanding today is a tribute to Robert S. Bourne, Longyear’s gardener, and his interest in and knowledge of flowers. A great deal of both planning and physical effort is involved in gardening. As Rudyard Kipling phrased it:

“Such gardens are not made

By singing, ‘Oh, how beautiful!’

And sitting in the shade.”

Early in the spring his work starts in the greenhouse, which over the years has been used to start flowers and vegetables for many of the gardens just described. His list of greenhouse plants begins with flowers such as, salvia, geranium, begonia, morning glory, nicotiana, snapdragon, petunia, canna, verbena, alyssum, and cockscomb; and ends with herbs, and vegetables like tomato, eggplant, broccoli, and so on. Annuals are put out in the gardens in the third or fourth week of May.

When asked what criteria he uses in his choice of flowers, he replied, “They are chosen according to hardiness, desired color effect, length of bloom, height, light requirements, whether perennial, biennial or annual, and cost.”

Robert Bourne has made some changes over the last few years. He has provided three seed beds in which to start perennials (e.g., delphinium) and biennials (e.g., pansy). In the spring of 1985 he started the three cut-flower beds and increased the fertility of many of the beds.

In the rose garden, rejuvenation was brought about by the addition of peat moss and leaf mold, better winter protection, pruning and fertilization, and by dusting against blackspot and fungi. The results of this work have been evident by the attention given this particular garden by Longyear Museum visitors.

It is hoped that these word pictures have given the reader an appreciation, not only of the wide scope and detail associated with Longyear’s gardens, but of the continuing effort that goes into making them a delight to all who view them.

The visitor to the Museum grounds may look for beauty and tranquility in the form and overall effect of a border garden or the sparkling color and intricacies of a single flower. He can be overwhelmed by the vibrant beauty of plot after plot of multi-colored tulips. But sometimes he may be just looking for tranquility in the simple perfection of an unfolding rose. The Longyear gardens give the visitor the opportunity to enjoy both the drama of an entire garden and the joy of a single flower.