After discovering that documents and artifacts from Mary Baker Eddy’s life were beginning to disappear, Mrs. Longyear made it her life’s work to find and preserve these important historic witnesses. Thanks to her efforts and the museum she founded, the thousands of letters, objects, and eight of Mrs. Eddy’s former residences that were saved will help tell Mrs. Eddy’s story to future generations.

In 1915, Mrs. Mary Beecher Longyear had only just begun collecting and preserving information on the life of Mary Baker Eddy and the pioneering activity of Christian Science when an interesting opportunity presented itself.

At this time, important firsthand evidence of the history of Christian Science was already in jeopardy. Old letters and documents were being disposed of, landmarks were falling into neglect or being sold, and people’s recollections were fading. Many eyewitnesses to this history — including Laura Sargent, William B. Johnson, and Joseph Eastaman — had by this time passed on.

Also, some of the houses in which Mrs. Eddy and her students had lived were becoming disfigured, being relocated, or torn down. All that remained of the Baker homestead — Mrs. Eddy’s birthplace in Bow, New Hampshire — were some of the original foundation stones.

A Preservationist Arrives Too Late

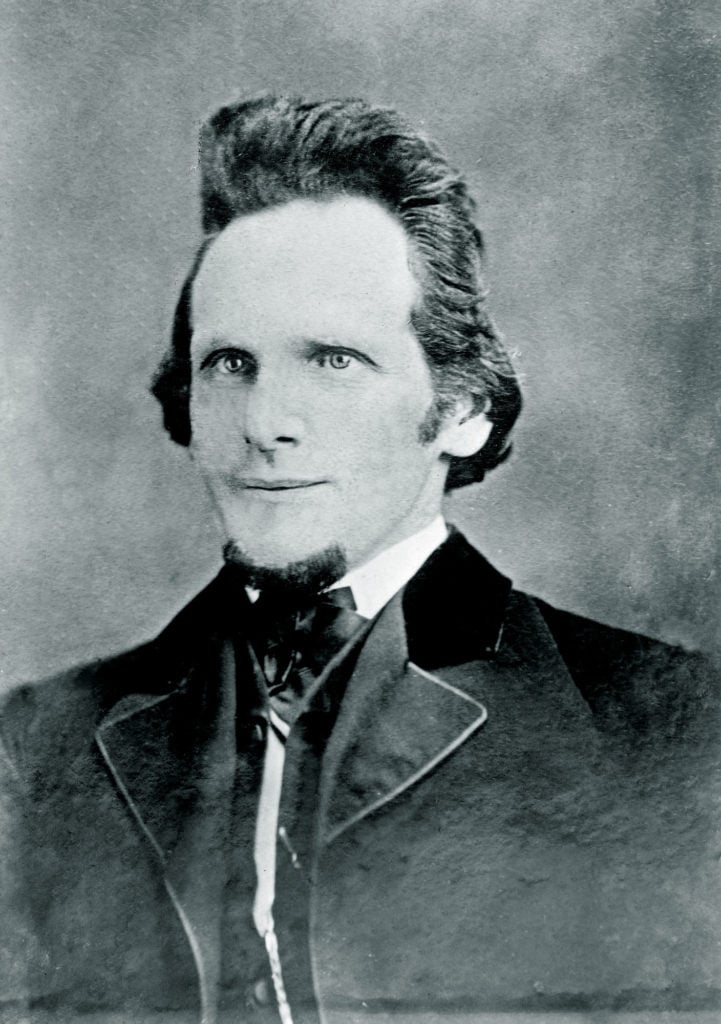

That year, 1915, Mrs. Longyear took the opportunity to preserve the history associated with the man who had come to have a special place in Mrs. Eddy’s heart — her husband, Asa Gilbert Eddy. After consulting historians of Mrs. Eddy’s life, she visited the town where Gilbert1 was born, Londonderry, Vermont. There she succeeded in locating the former Eddy farm house, built by Gilbert’s grandfather, and was hoping to recover Eddy family documents stored there. But she was too late. The man who had purchased the property some years earlier had disposed of its furnishings. All the Eddy family papers had been destroyed.

This story, told in a monograph by Mrs. Longyear titled The Genealogy and Life of Asa Gilbert Eddy and published in 1922, reveals the critical lesson she took to heart from this experience: in historic preservation, timing is crucial. If the preservationist does not act in a timely way, historical evidence may be lost forever. If the evidence of Gilbert Eddy could be lost so quickly, Mrs. Longyear concluded, then the work of preserving the history of Christian Science must begin promptly and in earnest.

Rescue Mission

In January 1918, Mrs. Longyear recorded in her diary her growing conviction that

The History of Christian Scientists and the establishing of the church must be written, so that no one in the centuries to come could doubt that Mary Baker Eddy and her faithful followers founded The First Church of Christ, Scientist.2

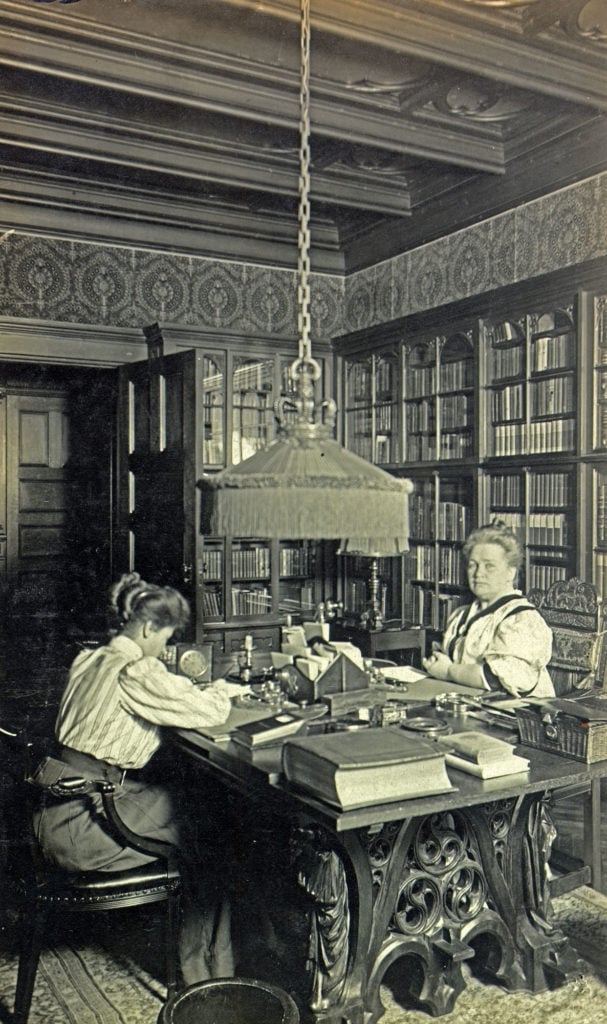

She began by gathering memoirs and portraits, and taking action to preserve documents, properties, and other artifacts belonging or related to Mary Baker Eddy’s life and work. Mrs. Longyear would write:

The most important thing in the whole world at this time, seems to me, is the preserving of the incidents and the authenticity of the history of the life of Mary Baker Eddy.3

Mary Longyear’s son Robert wrote of his mother’s motive for compiling a factual record of Mrs. Eddy’s story:

The more complete [the factual record] could be made, the less opportunity would there be in succeeding centuries to fabricate tissues of imagination in order to vilify [Mrs. Eddy] or sanctify her.4

Thus was launched a rescue mission which, in the space of less than twenty years, would salvage landmark houses, preserve documents and artifacts, solicit memoirs, commission portraits of early workers, and plan a museum to make this collection available for future generations.

There was just one minor problem: Mrs. Longyear knew almost nothing about historic preservation. But this former teacher and educator did understand the importance of historical evidence. The result was that her preservation work evolved through her step-by-step approach to learning. You might say, Mrs. Longyear’s methodology unfolded according to the need of the moment.

Gathering Evidence

To explore and understand questions about our past, it is essential that historians be able to consult evidence from the past. To make that possible, such evidence must be preserved. That was the mission Mrs. Longyear set for herself as she embarked on her quest for documents and artifacts from the life and work of Mary Baker Eddy, and of those who were closely associated with her.

In exploring the life of Gilbert Eddy, undaunted by the fact she was not able to save his family’s documents, Mary Longyear gathered all the firsthand factual evidence she could find — evidence that would help to answer the historian’s fundamental question, Who was Asa Gilbert Eddy?

As early as 1914, Mrs. Longyear had asked herself, “How came the name of Asa Gilbert Eddy, an almost unknown man, to be associated with [Mary Baker Eddy], her published work, and activities in the establishment of the Cause of Christian Science?”5

This question was sparked by her observation that few, if any, of her fellow Christian Scientists knew anything about the man whose family name, Eddy, graced the binding and title page of the book they studied every day, along with the Bible. Mrs. Longyear wrote:

Asa Gilbert Eddy was a true Christian Scientist, and he should never be forgotten … one whose name, through his marriage in [1877] with Mary Baker Glover, is now known throughout the world.6

Mrs. Longyear offered a pungent comment about the likely consequences of failing to gather facts about an historical figure like Gilbert Eddy:

… if authentic data of historical value should not be preserved by his contemporaries,… apocryphal legends would probably be invented, and the facts of his existence be hidden by their smothering dust.7

Preserving the Evidence

As she acquired evidence from Gilbert Eddy’s past, Mrs. Longyear sought out and gathered the recollections of people who had known him as Mary Baker Eddy’s husband and associate. She interviewed townspeople who had known the Eddy family, including a grammar school classmate of Gilbert who had memories of him that included vital information. Her diligent research did not exclude people who had fallen away from the Cause of Christian Science, such as Clara Choate and Arthur True Buswell. Both had played important roles in the early days of the movement, and recorded vivid memories of the Eddys.

She also retained an experienced genealogist to document Gilbert’s life in the Vermont farm community where he grew up, and to trace the Eddys’ roots back to the Eddy family in England. A photographer was employed by her to make a visual record of historic sites. The results of her research and findings were published in the monograph, The Genealogy and Life of Asa Gilbert Eddy.

She gathered information about other pioneer Christian Scientists as well, including some of Mrs. Eddy’s other students, such as Janet Colman, Julia Bartlett, Mary Eastaman, and Ellen Clarke — four of the twelve original First Members who, some thirty years before, had helped reorganize The First Church of Christ, Scientist. She asked them to write recollections of their introduction to Christian Science and of their association with Mrs. Eddy.

Mrs. Longyear also commissioned books on Christian Science history, including one by Putney Bancroft, a student from the 1870s in Lynn, and The History of the Christian Science Movement by William Lyman Johnson, whose father had been one of the original directors of The Mother Church.

Historic Houses

Within two years of her decision to save artifacts associated with Mrs. Eddy’s life, she began her most ambitious project: identifying and acquiring houses where the Founder of Christian Science had lived and worked. Before these houses could be saved, they had to be found, and so, in July of 1920, Mary Longyear went in search of these important landmarks. Traveling by automobile, she located several historic houses: the isolated country cottage in North Groton, New Hampshire, where Daniel and Mary Baker Patterson lived for five years; the house in Rumney, New Hampshire, where the Pattersons lived prior to their move to Massachusetts; the house on Paradise Road in Swampscott, Massachusetts, where, in 1866, Mrs. Patterson lay suffering from serious injuries after a fall in nearby Lynn, and where she remarkably recovered through prayer; Sarah Bagley’s house in Amesbury, Massachusetts, where the Discoverer of Christian Science twice found refuge and a place to teach; and, south of Boston in Stoughton, the Hiram Crafts and Alanson Wentworth houses, where Mrs. Eddy taught her earliest students and began writing about her discovery.

As a result of her 1920 house-hunting expedition, Mrs. Longyear’s collection soon included four historic houses. Some acquisitions took time, and some eluded her completely, but she was undeterred. Of one such property she said:

… if it is right for me to preserve this house, I will get it some day; if it is not God’s will, I do not want it!8

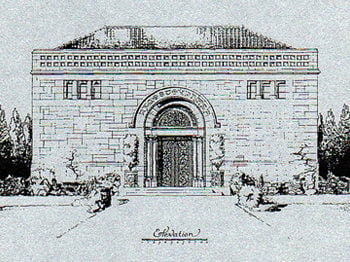

Longyear Museum

In 1923 Mrs. Longyear established the Longyear Foundation, which, after her passing in 1931, would continue to acquire many way marks of Christian Science history. To that end, Mrs. Longyear conceived a museum that would hold her collection, present the collection to the public, and be a center for research into the history of Mary Baker Eddy and the Cause of Christian Science. Unable to fund the construction of the museum building she had imagined, Mrs. Longyear’s will provided that her mansion continue to serve as her museum. That mansion was the precursor to the present Longyear Museum in Chestnut Hill, which opened in 2001, thus fulfilling its founder’s original vision.

Because of her foresight, another four historic sites have been added to the Museum’s collection over the years. When the Wentworths’ former home, where Mrs. Eddy resided from late 1868 to early 1870, was offered as a gift in 1961, the institution Mrs. Longyear had created was here to receive it.

In 1985 the Museum received another house as a gift — 62 North State Street in Concord, New Hampshire, where Mrs. Eddy lived and worked during the pivotal years from 1889 to 1892.

And in 2006 special donations to Longyear enabled the Museum to purchase two more significant landmarks: Mrs. Eddy’s former home on Broad Street in Lynn, Massachusetts, and her last home at 400 Beacon Street in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. These eight houses now in Longyear’s possession help to illumine for the visitor various stages of Mary Baker Eddy’s spiritual journey. As one crosses the threshold of each house, one is retracing the footsteps of the Discoverer of Christian Science. For generations to come, visiting these historic houses will help bring her story to life.

It’s worth noting that, in preserving these houses associated with Mrs. Eddy, Mary Longyear’s purpose had always been:

To … make them distributing centres of knowledge regarding her life ‘illustrating the ethics of Truth,’9 not as shrines where her personality would be worshipped.10

Working toward this goal, the Museum is in the process of restoring the Lynn house to the way it looked when Mrs. Eddy lived there from 1875 to 1882. The essential purpose of the restoration is to let the house tell its story to visitors — a story of importance to New England, national, and international religious history. In this house, the first, second, and third editions of Science and Health were completed for publication. Here the Christian Scientist Association, the Church of Christ (Scientist), and the Massachusetts Metaphysical College were established. And here, with her marriage to Asa Gilbert Eddy, Mary B. Glover became known as Mary Baker Eddy.

Similar objectives will guide the restoration plans for Mrs. Eddy’s last residence at 400 Beacon Street, Chestnut Hill, where she inaugurated The Christian Science Monitor.

“Consider the years of many generations”

Letters, records, artifacts, and buildings that attest to the progress of Christian Science and its Discoverer, help to recall historic events accurately — and especially the important lessons they teach. To remember the early days in the history of Christian Science is not just to reminisce, but to understand and appreciate anew what was required of Mary Baker Eddy and her early workers to bring Christian Science to humanity.

Understanding the lessons of the past is essential to living in the present. The Old Testament depicts Moses leading his people to the banks of the Jordan River and to the Promised Land, and telling them:

Remember the days of old, consider the years of many generations: ask thy father, and he will shew thee; thy elders, and they will tell thee.11

Nearly twenty years of Mary Longyear’s life were spent in this work of gathering and preserving houses, document, artifacts, and other materials that keep us mindful of those “days of old” — of the story of the Discoverer, Founder, and Leader of Christian Science and the early workers in the Christian Science movement.