This biography of John Munro Longyear complements that of his wife, Mary Beecher Longyear, written by their youngest son, Robert D. Longyear, for the Quarterly News, and published in Vol. 8, Nos. 3 and 4, Autumn 1971 and Winter 1971-72.

JOHN MUNRO LONGYEAR was born at the half-way mark of the nineteenth century, the son of John Wesley and Harriet Munroe Longyear of Lansing, Michigan. John Wesley Longyear was a lawyer in partnership with Schuyler F. Seager until appointed United States District Judge for the Eastern District of Michigan. He was also elected to Congress.

Young John was engaged in many business enterprises from the time he was seven years old. Several of his ventures ended ingloriously; however, his ideas continued to flow, and if not practical, were at least ingenious. Usually his ventures ended when either his money or his father’s patience was exhausted. He loved to build things, and had many pets both wild and domestic.

John received a good education, much of it in boarding schools, focusing his attention on mathematics and languages. Despite his parents’ teaching that fighting was to be avoided, he early learned that there were times when one must stand up, even to the point of confrontation, for what he believed was right.

On attaining the age of 14 in 1864 he was so tall and thin his friends called him “Skinny.” The next year, shortly after the assassination of President Lincoln, whom John had often seen while visiting the White House with his father, he suffered a physical collapse. For four or five years he was considered a semi-invalid, was removed from school, and spent much time on his father’s farm in Lansing. However, he proved to be an active invalid, building during his latter teens several flat-bottom skiffs which he used on the river that flowed past the rear of his father’s property. At eighteen, with the help of his brother and a friend, he built a printing press on which the friend printed a paper called “Young America”, to which the Longyear boys contributed articles. Later there followed the fabrication of a much larger press on which for about a year John published a newspaper called “The Echo.” Eventually he sold the press to a mercantile company which used it for many years thereafter.

John read eagerly, his favorite books being biographical, and he even tried his hand at writing. At the age of twenty, he published his own book, a semi-humorous “History of Lansing.” Forty-two years later in 1912 he was to write for his family, reminiscences of his ventures, adventures and misadventures during the intervening years. From these reminiscences came an interesting little book in 1960 entitled “Landlooker in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan”, edited by his daughter, Helen Longyear Paul, copyrighted by The Marquette County Historical Society.

In 1870 John went to work for his uncle for $10 a month, and board. Three years later, when he was twenty-three, his father’s law partner helped him obtain work at $10 a week as a “landlooker” in the wilds of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The job included surveying state mineral lands. He referred to himself as a “landlooker and timber cruiser”, and tramped the heavily timbered Upper Peninsula for five years. When he afterward became land agent for the Keweenaw Canal Company which had a grant of thousands of acres of forest and mineral land in the heart of the Upper Peninsula — there was no more time for landlooking.

His years of surveying the rugged timber and mineral land had well acquainted him with the terrain and the virtually untapped riches of the area and earned him the respect of those investors who needed his knowledge. His life in the woods also acquainted him with the wild life of the area which abounded in big game. He said he never actually saw the grey timber wolf, the most cowardly of animals, nor the beaver, though he often heard the lonely howling of the one, and came upon the clever handiwork of the other. Both were extremely wary of men.

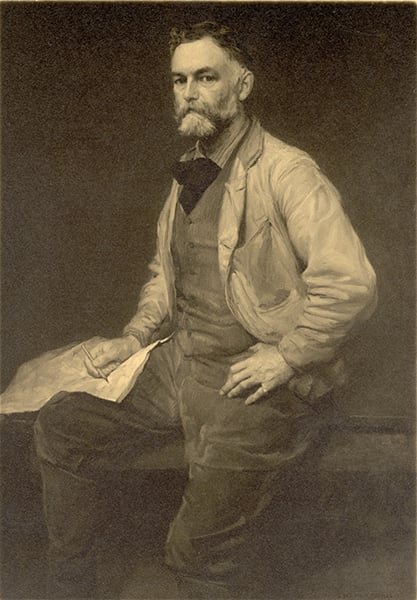

In the woods John sometimes faced dangers often so acute that once or twice his life seemed endangered; but his twenty-four-hour relationship with nature developed great physical strength and stamina, and engendered in him resources both physical and mental that always proved equal to the demands of each experience. He felt that being obliged to make decisions and act on his own had inculcated strength and self-reliance. At twenty-three John Longyear was quite handsome — six feet, two inches tall, rangy, with clear, intelligent brown eyes, curly black hair and a beard.

He became a Mason in 1871 by joining Lansing Lodge No. 33 in Lansing, Michigan, and affiliated with Marquette Lodge No. 101 at Marquette. He joined the Scottish Rite Bodies at Marquette in November 1919.

In Marquette, he teamed up with Abe Matthews whom he had met in 1873, and Matthews opened an office for them a year later to engage in the land business. Their partnership, based on mutual trust, flourished without benefit of written contract until early in 1880 when it was dissolved by mutual consent.

During a visit to Lansing in 1876 he gave up smoking, but found the desire returning when he went back to the woods where a twilight smoke had always seemed so enjoyable. However, the time came when the generous offer of a woodsman friend to share his treasured, weathered, odorous old pipe cured him of the habit permanently.

In 1878, making his way out from his last wood-cruising trip, John met Theodore M. Davis, president of the Lake Superior Ship-Canal Railway and Iron Company, and thus began a friendship and business relationship which lasted over thirty-five years. With a signed contract in his pocket, which John felt assured his future, he set off to propose to the girl he had met the previous February and had fallen in love with — Mary Beecher, an attractive young lady who had come to Marquette to teach school. They were married January 4, 1879.

Almost from the beginning of his landlooking activities John had had in mind the operation of his own iron mine. In 1885 his dream was realized as operations were begun in his own mine, “Norrie.” Now he was on his way to success!

John Longyear crammed into the ensuing years a great diversity of business activities, most of which he claimed made him very little money. Several were rather dismal investments to help friends. There was a button fastening company which took eighteen years and a $200,000 investment before it evolved into a profit-making establishment. In 1888 he dipped into gold mining, and out of the thousands of dollars swallowed up by this mine, he realized only one dividend of $187. Naturally, he was much involved in timber and mineral leases. He was twice president of banks and helped organize the Huron Mountain Club located on 10,000 acres of lakefront property about forty miles across the water from Marquette. He purchased a steamer to ferry the members there and back. In the Yellow Dog River area he purchased land and began the construction of another club in 1898. However, a number of years later, it was converted into a club for boys, and was named “Sosawagaming” (Yellow Dog).

In 1890 while Mr. Longyear was mayor he began construction of a large brownstone house in Marquette . He was reelected mayor in 1891. His active desire to boost the town caused him to complain that there was more work than honor involved.

If any speckled trout are now found in lves Lake, Michigan, they may possibly be descendants of fish stocking expeditions by John Longyear in 1893. On the shore of Lake lves he later purchased· timber, swamp and stump land for a farm on which clearing was begun in 1896, and building in 1897. Eventually from it was harvested chestnuts, a variety of fruits and garden produce. When the husband of his daughter, Abby Alton T. Roberts, was made manager, chickens and Holstein cattle were added to put the farm on a paying basis.

With the aid of J. P. Morgan, famous financier of that era, a business transaction was consummated, so fabulous that it made headlines all over the world: MADE A MULTIMILLIONAIRE BY A STROKE OF MORGAN’S PEN. It brought such a flood of promotional schemes that only friends’ letters could be answered. Since there was no money immediately forthcoming, Mr. Longyear wrote: “I could only assure my friends that I found it impossible to live up to the twenty-four-million-dollar reputation without the money, and some of them were much offended.”

Mr. Longyear recorded his reaction when he first heard of Christian Science in 1888: “I thought it the most unreasonable thing possible.” He said that up until 1900 current ideas on religion did not appeal to him as reasonable and he didn’t give them much attention. According to him, until their trip to San Francisco, California in 1891, his wife Mary was only mildly interested in Christian Science. While there they met a lady from Cleveland, Ohio who told them of her healing of cancer by Christian Science after doctors in America and Europe had pronounced her’s a terminal case. In 1912 he wrote of her, “She is still living, in good health.”

Several years earlier, the Longyears’ youngest son had been stricken suddenly and passed on, leaving Mrs. Longyear completely distraught. Through alternating periods of prayer and despair she had come upon the textbook, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy, and felt that it was showing her the way to at least peace of mind.

During their visit to California their eighteen-month-old son, Jack, was also stricken. When Mary decided to try Christian Science, Mr. Longyear found Miss Sue Ella Bradshaw, a Christian Science practitioner whom he described as “a charming, bright-looking woman”, and engaged her to take the case. She went to the hotel to talk to his wife and the next morning Jack was completely well. Mr. Longyear, however, felt that he would probably have been well anyway. He said, “I was unable to believe that just thinking would cure croup.” Because it seemed to be doing his wife so much good, he “tolerated” Christian Science for several years, but he felt it was “too intangible” for anything but “mental, or imaginative complaints”, and must fail if the illness were really serious.

In 1897 he himself came down with muscular rheumatism, a complaint from which he had suffered intermittently for some twenty years. The condition was extremely painful and sometimes incapacitated him for several weeks. It usually took at least two weeks for medical aid to relieve him. He wrote about the incident:

“I went to bed and Mary asked me if I wanted Christian Science treatment. I thought that this would be a good chance to show her where there was a real sickness Christian Science could not remove it and I said I would try it … I was in much pain all that night and during the following day. The second night I slept well and in the morning I was entirely free from pain. It was surprising, but I had experienced the sudden relief before, in milder attacks, and I supposed this to be a similar case. I was a little annoyed that it should happen just as I was trying to make a test. I confidently looked for a return of the malady … I waited three years for the rheumatism to return but it did not. Then I made my tardy acknowledgment that I had been healed by an appeal to Spirit and that I had experienced an application of Divine Love in healing. The same Love that healed in Galilee nearly nineteen hundred years before.” That was the end of the rheumatism.

In his reminiscences Mr. Longyear included the inspiring story of his ex-partner, Abe Matthews, who had become so blind that he was settling his business affairs which he could no longer handle. Eye specialists he had consulted could neither diagnose the problem nor otherwise help him.

One day Mary Longyear, who had just returned from Europe, was out walking and saw him in his yard with some of his children. He called to her, asking if he could talk to her for a few minutes. He wished to know if she still believed in Christian Science. She replied enthusiastically that she did. Then he told her he had been waiting for her return, intending if she still believed in it, to try it for himself. Mr. Longyear wrote: “He started treatment with a practitioner that day. In two weeks he was reading with ease and resumed his business. This was ten or twelve years ago and he is still in good condition. His wife studied Science and has been a successful practitioner for several years, has had many great demonstrations in healing.”

The dismantling of the Marquette house in 1903 and its removal to Brookline, Massachusetts, a distance of 1,300 miles, evidenced to a degree the initiative Mr. Longyear always displayed when confronted with a challenge. This decision was made when an ore-carrying railroad was allowed to extend its tracks along the lake front essentially circling their Marquette home. He arranged with the original architects to have the house dismantled, each piece identified, transported on 190 railroad cars and reconstructed on Fisher Hill in Brookline. The new house, about fifty percent larger than the original, was occupied in March 1906, although all the rooms were not then completed. The story of this remarkable event is given in the article, “From Marquette to Brookline” (Quarterly News, Spring, 1969, Vol. 6, No. 1)

Ultimately, the Longyear home, through arrangements made by Mrs. Longyear, with her husband’s counsel and consent, became the headquarters of Longyear Foundation, and later in 1937 the Longyear Museum. For a time it also housed the Zion Research Foundation founded by the Longyears for the purpose of Biblical research.

In 1918, during one of their trips to California, they were introduced by Miss Maurine Campbell, of “Busy Bee” fame, to J. Robert Atkinson, blinded in young manhood by the accidental discharge of his gun. His own need for reading material had driven him to try to improve the quality of reading material for other sightless people. So impressed were Mr. and Mrs. Longyear with what he had thus far accomplished that they offered to subsidize his work by $5,000 a year for five years. Accepting their offer, Mr. Atkinson had received, at the termination of the gift in 1924, a total of $34,000 and had proven himself preeminently worthy of their trust. (See “J. Robert Atkinson … benefactor of the blind”, Quarterly News, Winter, 1972-73, Vol. 9, No. 4).

In 1901 Mr. Longyear began his adventures in the coal fields of the Spitsbergen Archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. Spitsbergen, so named because of its broken mountain peaks, is a bout the size of the State of Maine, and its northern limits are some 600 miles from the North Pole. This American operation, in which Mr. Longyear played a major role, lasted for fourteen years.

Nathan Haskell Dole authored a book entitled “America in Spitsbergen”, a two-volume account of the history of Spitsbergen and of the men who succeeded finally in conquering its rugged terrain and bitter weather to wrest from it the vast mineral wealth it contained. These volumes are generously illustrated with photographs supplied by Mr. Longyear. In the foreword of Volume I, Mr. Longyear wrote: “How successful the American engineers and foremen were in developing this enterprise is reflected in the remarkable freedom from serious accidents and from loss of life, … A large share of this immunity from violence was due to the strict regulations forbidding the importation and use of alcoholic drink.”

In “An Appreciation” in Volume I, Mr. Dole wrote that he deeply regretted that Mr. Longyear did not live to see the volumes published, although he had “twice read the typoscript of the work, had made many modifications and suggestions, and had carefully gone over all the page proofs, except about 200 pages of the second volume.” Mrs. Longyear carried the work to completion. To all who read “America in Spitsbergen” Mr. Dole felt it must be clear … “that John Munro Longyear was a man of remarkable ability and character. He had accumulated a large fortune but was entirely unspoiled by his success. He was free from conceit and from arrogance. He was friendly, generous, full of humor, sincere, gracious, and a good story-teller; he had traveled widely, seen many men and many countries, gathered much information and had learned to view with a kindly eye the faults and follies of his fellowmen.”

John Munro Longyear, hardworking husband and father, and good friend to many, strove throughout his lifetime to enrich the lives of his loved ones and the lives of those he called friends, as well as giving full expression to his personal need to ever broaden the horizons of his own life.

On January 4, 1925 his wife recorded in her own diary, three years after his passing: “Forty-six years ago I married one of the finest and noblest men I have ever met.”